Galectins: Double-edged Swords in the Cross-roads of Pregnancy Complications and Female Reproductive Tract Inflammation and Neoplasia

Article information

Abstract

Galectins are an evolutionarily ancient and widely expressed family of lectins that have unique glycan-binding characteristics. They are pleiotropic regulators of key biological processes, such as cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, signal transduction, and pre-mRNA splicing, as well as homo- and heterotypic cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions. Galectins are also pivotal in immune responses since they regulate host-pathogen interactions, innate and adaptive immune responses, acute and chronic inflammation, and immune tolerance. Some galectins are also central to the regulation of angiogenesis, cell migration and invasion. Expression and functional data provide convincing evidence that, due to these functions, galectins play key roles in shared and unique pathways of normal embryonic and placental development as well as oncodevelopmental processes in tumorigenesis. Therefore, galectins may sometimes act as double-edged swords since they have beneficial but also harmful effects for the organism. Recent advances facilitate the use of galectins as biomarkers in obstetrical syndromes and in various malignancies, and their therapeutic applications are also under investigation. This review provides a general overview of galectins and a focused review of this lectin subfamily in the context of inflammation, infection and tumors of the female reproductive tract as well as in normal pregnancies and those complicated by the great obstetrical syndromes.

INTRODUCTION TO THE GALECTIN FAMILY

More than half of all human proteins are glycosylated [1], and glycans are attached to various additional glycoconjugates (e.g. glycolipids) besides glycoproteins. Because of the abundance of glycans intra- and extracellularly and also their high complexity, glycans can store orders of magnitude larger biological information than other biomolecules (e.g. nucleic acids and proteins) [2,3]. Lectins are sugar-binding proteins, which are not an antibody or an enzyme, and can specifically bind glycans without catalyzing their modification [3,4]. The interactions of lectins with glycans are pivotal in the regulation of a wide variety of interactions of cells with other cells, the extracellular matrix or pathogens [2-4].

Galectins belong to a subfamily of lectins based on their unique structural and sugar-binding characteristics, since their carbohydrate-recognition domains (CRDs) contain consensus amino acid sequences and they specifically bind beta-galactoside–containing glycoconjugates [5-8]. Galectins are the most widely expressed animal lectins; they have been found in species ranging from sponges to humans [7-9]. They regulate a wide variety of key biological processes, such as cell growth, proliferation and differentiation, apoptosis, signal transduction, pre-mRNA splicing, as well as cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions [2,5-9]. Galectins are also pivotal in immune responses since they regulate host-pathogen interactions, acute and chronic inflammation, and immune tolerance (Fig. 1) [8,10-13]. Moreover, some galectins are central to the regulation of angiogenesis in the placenta and in tumors [14,15]. Interestingly, galectins can have opposing functions, and the same galectin can also have varying or contrasting effects based on the biological context and the microenvironment since their functions depend on the differentiation or activation status of the cell, the dynamic changes of their glycan partners on the cell surfaces, the redox and oligomerization status of the galectin, or its intra- or extracellular localization [8,11,16,17]. Thus, galectins’ double-edged action may sometimes be beneficial or harmful to the organism.

Galectins in inflammation and infection. The effects and expression changes of galectins in immune cells are depicted around the three-dimensional model of galectin-1 (Protein Data Bank accession number: 1GZW) [35,55]. Galectins’ effects are biological-context and microenvironment dependent and relate to the differentiation or activation status of the cell, the dynamic changes of the glycan partners of galectins on cell surfaces, the redox and oligomerization status of the galectin, or its intracellular or extracellular localization. ECM, extracellular matrix; HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus 1; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NK, natural killer; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. Parts of the figure are adapted from Than et al. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2012; 23: 23-31, with permission of Elsevier [16].

The fundamental functions of galectins indicate that they are strongly associated with reproductive functions as well as the establishment and maintenance of pregnancy [10,18-28]. Indeed, some galectins are highly expressed at the maternal-fetal interface [10,18-39], and these are evolutionarily linked to placental evolution in eutherian mammals [5,7,9,26,27,40]. Moreover, the dysregulated expression of these galectins in pregnancy complications has been increasingly documented [10,23,32-36,38,41-51]. Galectins have also been implicated in inflammatory, infectious and malignant diseases of the reproductive tracts. Of importance, the same galectins may be functional in pathways commonly shared by physiological and pathological, placental, and tumor developmental processes (e.g. cell invasion, angiogenesis, and immune tolerance). This review aims to give a general overview of galectins and also a focused review of them in the context of inflammation, infection and tumors in the female reproductive tract as well as in normal and complicated pregnancies.

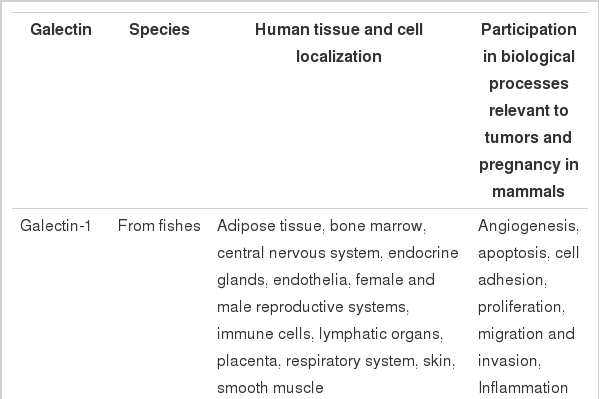

Structural features of mammalian galectins

Galectins were originally termed “S-type lectins,” where “S” refers to their free cysteine residues [6,8]. Galectins or galectin-like proteins were also discovered in fungi, viruses, and even plants [8,9]. Because of the diversity between mammalian and non-mammalian galectins, their nomenclature has diverged as mammalian galectins have been named using sequential numbering, while non-mammalian galectins have retained specific names (Table 1) [6]. Nineteen galectins have been identified in mammals to date, 13 of which were found in humans [9,27]. These galectins can be divided into three structural groups [5-8]: (1) “proto-type” galectins (-1, -2, -5, -7, -10, -13, -14, -15, -16, -17, -19, -20) contain a single CRD of ~130 amino acids, which homodimerize [5-8,52]; (2) “tandem-repeat-type” galectins (-4, -6, -8, -9, -12) contain two homologous CRDs connected by a short linker sequence. These may differ in their sugar-binding affinities and enable multivalent binding activity [5-7,52]; and (3) “chimera-type” galectin-3, which contains a C-terminal CRD and an N-terminal non-lectin domain important for multimerization and cross-linking as well as functional regulation [5-7,52].

Although the amino acid sequences of galectins have diverged during evolution, the topologies of their CRDs are very similar, often described as “jelly-roll;” these are β-sandwiches consisting of five- and six-stranded anti-parallel β-sheets (Fig. 1) [6-8,53-55]. Highly conserved in galectin CRDs are eight residues, which are involved in glycan-binding by hydrogen-bonds as well as electrostatic and van der Waals interactions [53,55]. All galectins specifically bind beta-galactosides [5-8] except galectin-10, which has more affinity to beta-mannosides [53]. Of interest, some galectins have high affinity for poly-N-acetyllactosamine or ABO blood-group containing glycans, and the latter is responsible for their hemagglutinin activity [52,56-58].

Functional characteristics of mammalian galectins

Galectins have multiple functions both inside and outside the cell (Table 1) [8,59,60]. Intracellularly, certain galectins can modulate cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, and migration [8,59,60] via protein-protein interactions [8,59,60]. Some galectins (-1 and -3) shuttle into the nucleus where they function in pre-mRNA splicing [8,59]. In spite of the fact that they do not have a secretory signal sequence, galectins can be secreted from cells via a non-classical pathway, avoiding the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, which is characteristic of only a small set of proteins (e.g. high-mobility group box 1 protein, interleukin-1β) [61]. Extracellularly, galectins predominantly localize to lipid rafts on cell surfaces [8,52,62] where they exert their functions through binding to cell-surface or extracellular matrix molecules, which carry their glycan ligands [2,7,8,11,13,52,63,64]. They can form multivalent galectinglycan arrays, so-called lattices, by cross-linking their ligands on cell surfaces, and these lattices can organize lipid raft domains and modulate cell signaling for cell growth, metabolic functions, cytokine secretion, and survival, as well as many other intracellular and extracellular interactions [8,11,13,17,52,65]. Some galectins can also affect cell adhesion and apoptosis, and activate or inhibit immune responses [8,11,13,63]. An interesting trait of galectins is that their secretion is heightened upon response to stress conditions (e.g. inflammation and infection) and cellular damage (e.g. necrosis); therefore, galectins have been implicated as “alarmins” which signal tissue damage and elicit effector responses from immune cells, thereby promoting the activation and/or resolution of immune responses [12,35,64,66].

Expression profile of human galectins

Accumulating evidence in various species shows that galectins have distinct but overlapping tissue expression patterns in mammals including humans (Table 1) [6,8,27,67,68]. Among prototype galectins, galectin-1 and galectin-3 have a wide expression pattern in humans, galectin-1 being the most abundant in the endometrium/decidua [8,26,67]. Among tandem-repeat-type galectins, galectin-8 and galectin-9 have a broad and complex expression pattern. Alternatively spliced isoforms of galectin-8 are differentially expressed in various tissues [8,39,67] similar to galectin-9, which is encoded by three genes [67]. These galectins are highly expressed in the female reproductive tract and at the maternal-fetal interface [8,10,18-23,25,27,32,34,35,37-39,69]. Some galectins (-2, -4, -5, -6, -7, -12) have more restricted tissue distribution [8,67]. Of note, the expression of galectins in the chromosome 19 cluster is very restricted. Among these, galectin-10 is expressed in T regulatory (Treg) cells, as well as eosinophil and basophil lineages, and forms the so-called Charcot-Leyden crystals at sites of eosinophil-associated inflammation [53,70]. The expression of galectin-13, -14 and -16 is predominant in the placenta, while galectin-17 expression is low in any tissues [27,29,67,71]. Interestingly, these galectins (-10, -13, -14, -16, -17), which are expressed from the chromosome 19 cluster, emerged via birth-and-death evolution in anthropoid primates and may regulate unique aspects of pregnancies, including maternal-fetal immune regulation and tolerance in these species [16,27,72].

GALECTINS IN INFECTION AND INFLAMMATION OF THE FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE TRACT

Due to the multiple functions of galectins, they have been implicated in pathways and processes fundamental for reproductive functions in both the pregnant and non-pregnant state. Data on the expression profile and functions of galectins regarding female reproductive tissues has recently emerged. Accordingly, a growing body of evidence suggests that galectins play important roles in immune responses in inflammatory and infectious diseases and in the development of various tumors of the female reproductive tract.

Galectins in infection of the female reproductive tract

Recent evidence suggests that the outcome of infection is also significantly influenced by galectins (Fig. 1) as these glycanbinding proteins acts as regulators of host-pathogen interactions [12]. Similar to alarmins, upon tissue damage and/or prolonged infection, cytosolic galectins can be passively released from dying cells or actively secreted by inflammation-activated cells through the non-classical ‘leaderless’ secretory pathway [12]. Once exported, galectins act as soluble or membrane-bound ‘damage associated molecular patterns’ [12,66] or ‘pathogen associated molecular patterns.’ The latter, due to their CRDs, can specifically recognize pathogen cell surface antigens like pattern recognition receptors [12,66,73]. Indeed, various galectins have been shown to bind a wide range of pathogens, which display their ligands on the surfaces, such as Gram-positive bacteria (e.g. Streptococcus pneumoniae), Gram-negative bacteria (e.g. Klebsiella pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Haemophilus influenzae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Porphyromonas gingivalis,and Escherichia coli), enveloped viruses (Nipah and Hendra paramyxoviruses, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]-1, and influenza virus A), fungi (Candida albicans) and parasites (Toxoplasma gondii, Leishmania major, Schistosoma mansoni, Trypanosoma cruzi, and Trichomonas vaginalis) [12,74-82].

It is interesting that the co-evolution of microbes and host glycocalyx components is a continuously ongoing process, and the evolutionary arms race, the “Red Queen effect,” has strongly impacted pathogenic and invasive properties of those microbes in relation to glycocalyx components that now infect our species [73,83]. For example, it has been observed that galectin-3 provides advantage for Helicobacter pylori in binding to gastric epithelial cells, and thus, enhances the rate of infection [78]. Similarly, galectin-1 increases the spread of human T-cell leukemia virus type I by stabilizing both virus-cell and uninfected-infected T cell interactions [79]. Interestingly, due to their ligand-binding specificity, galectin-1, but not galectin-3, can influence the sexual transmission of HIV-1 through the increase of viral adsorption kinetics on monocyte-derived macrophages [77,84]. Based on this data, the progress of microbial infections seems to depend on the expression and localization of various galectins in the route of infection.

The most studied galectin in infections of the female reproductive tract is galectin-3. It is expressed on the apical side of the non-ciliated epithelial cells in the Fallopian tube and can bind the lipooligosaccharides on Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Since galectin-3 participates in several endocytotic processes, such as its own reuptake, it can facilitate the invasion of human epithelial cells by gonococci [74]. Interestingly, in response to gonococcal infection, tumor necrosis factor α production increases in the Fallopian tube and induces apoptosis of cells not protected by galectin-3. Since the presence of gonococci is limited mainly to galectin-3–positive non-ciliated cells, galectin-3 promotes the survival of this pathogen [74]. The induction of this anti-apoptotic effect of galectin-3 can be observed when it is phosphorylated in response to infection, which increases the ability of galectin-3 to induce arrest in the G1 growth phase [85] and to perpetuate the survival and proliferation of infected cells [78].

Besides galectin-3, galectin-1 and -7 can also bind Trichomonas vaginalis. Surprisingly, the interaction of galectin-7 with this pathogen is not carbohydrate-mediated, in contrast to galectin-1, which is expressed by human cervical and vaginal epithelial cells, the placenta, as well as endometrial and decidual tissues [80,81]. Galectin-1 and -3 are capable of binding purified lipophosphoglycan, which covers the whole surface of Trichomonas vaginalis [86]. Galectin-1 is thought to be a general attachment factor for this parasite and promotes the colonization of the female and male reproductive tracts, which could lead to vaginitis, bacterial vaginosis, increased risk of cervical cancer, human papillomavirus and HIV infection in females, endometritis, infertility, preterm birth, and low birth weight [81]. In addition, female infants could get infected during birth and then would remain symptomless until puberty [87].

In contrast to the harmful roles of galectins during Trichomonas vaginalis infection, upon invasion of this parasite, vaginal epithelial cells release galectin-1 and -3, and these galectins modulate vaginal epithelial cell inflammatory responses by triggering resident immune cells, and thus, contribute to the elimination of this pathogen [81]. In addition, secreted galectin-3 initiates the trafficking of phagocytic cells to the site of infection by supporting neutrophil adhesion to the endothelial cell layer, and this also increases its phagocytic activity [78,88].

Galectins in inflammation of the female reproductive tract

Among various inflammatory diseases of the female reproductive tract, endometriosis has been the most studied in regard to galectins. Endometriosis is an inflammatory disease of reproductive-aged women, and it is strongly related to consequent infertility [89]. The pathophysiology of endometriosis involves chronic dysregulation of inflammatory and vascular signaling [90], processes in which galectins are operational. Not surprisingly, galectin-1 and -3 are overexpressed in various forms of endometriotic tissues [91-94]. Moreover, higher galectin-3 concentrations are also detected in peritoneal fluid samples from women with endometriosis than from controls [93]. Functionally, it has been shown that corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) and urocortin, two neuropeptides that are also overexpessed in endometriosis, are involved in the up-regulation of galectin-1, acting through CRH receptor 1, in a human endometrial adenocarcinoma cell line and in mouse macrophages [94]. This up-regulation of galectin-1 may contribute to T cell apoptosis favoring the establishment, persistence and immune escape of endometriotic foci [90]. Moreover, galectin-1 may promote the vasculogenesis of endometriotic tissues since it orchestrates vascular networks in endometriotic lesions as demonstrated in mice with or without galectin-1 deficiency [92], and a neutralizing antibody against galectin-1 reduces the size and vascularized area of endometriotic lesions within the peritoneal compartment [92].

Recent data have suggested that galectin-3 may play a role in the development of pain due to endometriosis since it is involved in myelin phagocytosis, Wallerian degeneration of neurons, and triggers neuronal apoptosis induction after nerve injury [95]. In fact, galectin-3, overexpressed in endometriotic foci, could induce nerve degeneration, since there is a close morphological relationship between nerves and endometriotic foci by means of perineurial and endoneurial invasion, especially in the most painful form of the disease [96]. Interestingly, neurotrophin, a nerve growth factor strongly expressed in endometriosis, up-regulates galcetin-3 expression [91]. These data underline the importance of galectin-1 and -3 in the pathogenesis of endometriosis.

GALECTINS IN TUMORS OF THE FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE TRACT

The multifunctional role of galectins in cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, adhesion, invasion, and angiogenesis explains why they are associated with different tumors. Indeed, many cancers have differential galectin expression compared to healthy controls, including tumors of the female reproductive tract (Fig. 2) [97]. Of interest, certain galectins have been functionally implicated in dysregulated pathways in tumor developmental processes, which are physiologically tightly regulated during placental development (e.g. invasion, angiogenesis, and immune tolerance) [14,16,17,98]. In addition, galectins may also be dysregulated in tumor-associated stromal cells or endothelial cells [15,99], and their glycan ligand expression and/or glycosylation pattern can also be affected [100,101]. Most of these studies focused on galectin-1 and -3, but an increasing number of recent studies also investigated galectin-7, -8, and -9.

Galectins in neoplasia of the female reproductive tract. The functional effects of various galectins in tumorigenesis and their expression changes in certain types of female tract neoplasia are depicted. The effects of galectins are biological-context and microenvironment dependent. Galectins’ expression changes can be different according to the stage and type of various neoplasia as well as the type of the expressing cell. DC, dendritic cell.

Galectin-1 is differentially expressed in several tumors in the female reproductive tract. An increased expression of galectin-1 protein is found in endometrial [102,103], breast [104], ovarian [105], and cervical [106] cancers. The intensity of galectin-1 expression also increases according to the pathologic grade of cervical [106] or breast [104] cancer and correlates with the depth of invasion of the cervical cancer and in lymph node metastases [107]. In breast cancers, not only tumor cells but also cancer-associated stromal cells have elevated galectin-1 expression [99]. In squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the uterine cervix, the intracellular expression of galectin-1 in tumor cells is higher than in the tumor-associated stroma, and galectin-1 is an independent prognostic factor associated with local recurrence and cancer-specific survival in stage I–II cervical cancer patients undergoing definitive radiation therapy [108]. It has been suggested that galectin-1 mediates radio-resistance through the H-Ras signaling pathway that is involved in DNA damage repair in cervical carcinoma cells [109], underlining the importance of galectin-1 in tumorigenesis and therapy.

Galectin-3 is down-regulated in cervical carcinomas, and its expression is correlated to histopathologic grades [110]. It is also down-regulated in advanced uterine adenocarcinoma cells compared to normal adjacent endometrial cells [102,103]. Moreover, galectin-3 expression is predominantly detected in the cytoplasm and/or nucleus of uterine or breast cancer cells [102,111,112]. Of note, those uterine endometrioid adenocarcinomas, where galectin-3 is detected only in the cytoplasm, are characterized by deeper invasion of the myometrium [102]. In addition, the neoplastic epithelium within ‘MELF’ (microcystic, elongated, and fragmented glands) areas shows a consistent reduction in galectin-3 protein expression, often contrasting with the adjacent galectin-3–positive conventional glands and reactive stromal cells. Conversely, intravascular tumor foci often show cytoplasmic and nuclear galectin-3 immunoreactivity [112]. On the contrary, in some ovarian and endometrial carcinomas, including clear cell, serous, endometrioid, and mucinous ovarian carcinomas, higher galectin-3 expression is seen either by immunohistochemistry [113-116] or by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction [117]. Which biological functions of galectin-3 are utilized by tumor cells depends on the localization of this galectin: nuclear galectin-3 may function in mRNA splicing, cell growth and cell cycle regulation; cytoplasmic galectin-3 may induce apoptosis resistance; and secreted galectin-3 modulates cellular adhesion and signaling, immune response, angiogenesis and tumorigenesis by binding to cell surface glycoconjugates such as laminin, fibronectin, collagen I and mucin-1 [111,118-121]. For example galectin-3 may mediate chemoresistance via regulating the cell cycle as responders to chemotherapy have a higher proliferation activity than non-responders. This finding was strengthened by experimental results after knocking down galectin-3, which increases the fraction of cells in the S-phase of the cell cycle and decreases the expression of p27 cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor in clear cell carcinoma cell lines [114]. Moreover, the ability of galectin-3 to protect cells against apoptosis induced by various agents, working through different mechanisms, suggests that galectin-3 acts in a common central pathway of the apoptotic cascade, involving protection of mitochondrial integrity and caspase inhibition [85,122-128]. Of importance, a galectin-3 polymorphism, the substitution of a proline with histidine (P64H), results in susceptibility to matrix metalloproteinase cleavage and acquisition of resistance to drug-induced (e.g. doxorubicin, staurosporine, and genistein) apoptosis [129-131], and homozygosity for this H allele is associated with increased breast cancer risk [130]. On the other hand, the Pro64 variant and phosphorylation of galectin-3 at Ser6 seems to be important in tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)–induced apoptosis of human breast carcinoma cells [131,132]. Interestingly, nicotine induces the expression of galectin-3 in breast cancer cells and in primary tumors from breast cancer patients through its receptor and STAT3 expression, increasing the anti-apoptotic effect of galectin-3, and suggesting detrimental effects of smoking [133].

Galectin-7 up-regulation in cervical cancer is associated with better overall survival after definitive radiation treatment [134], and similar observations were made in other cancers (e.g. urothelial and colon), as well [135-138]. On the other hand, galectin-7 induces chemoresistance in breast cancer cells via impairing p53 [139] or via mutant p53-induced galectin-7 expression [140].

Galectin-8 is expressed by various ovarian and breast cancer cell lines [141]; however, only one study reported that breast cancer tissues constitute the only group of tissue to exhibit a higher immunohistochemical galectin-8 expression in the malignant, as opposed to the benign, tumors [142].

Galectin-9 can be detected in normal epithelium and endocervical glands, and it has decreased expression in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and SCC. High-grade intraepithelial lesions express less galectin-9 than low-grade lesions. Unexpectedly, galectin-9 expression is higher in well-differentiated SCC compared to moderate or poorly differentiated SCCs. These results imply the involvement of galectin-9 in the differentiation of cervical cancer cells [143,144]. Recently, galectin-9 has been implicated as a prognostic factor in breast cancer [145]. The various roles of galectin-9 in tumorigenesis, including the participation in apoptosis, cell cycle control, adhesion, aggregation, migration, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, and immune escape, have recently been summarized in a review [146].

Galectins in tumor invasion

The invasive and metastatic phenotype of cancer cells is presumably associated with a specific pattern of expression of cell adhesion molecules that allows for crossing through the basement membranes and creating distant metastases. Emerging data demonstrate the role of galectins in metastasis events, although the data is conflicting, possibly due to the various effects that galectins may have according to the microenvironmental and physicochemical changes.

Galectin-1, a laminin-binding molecule, may contribute to the invasiveness of cancer cells, since higher galectin-1 binding to cancerous epithelial cells was observed in stage III/IV endometrial carcinomas than in lower stage tumors [102,147]. Indeed, the down-regulation of galectin-1 by siRNA results in the inhibition of cell growth, proliferation and invading ability of various cervical cancer cell lines [107].

Galectin-3, when localized to the cell surface, is involved in Thomsen-Friedenreich antigen (Galβ1-3GalNAcα1 disaccharide)-dependent homotypic cell adhesion and heterotypic cancer cellendothelial cell contact [148,149]. Therefore, the decreased expression of this lectin could reflect the ability of cancer cells to detach from each other before invasion. Nuclear and cytoplasmic presence of galectin-3 implies that its localization and phosphorylation status is correlated with the proliferation status of the cells [150]. All aspects of this topic have been reviewed elsewhere[151].

Galectin-7 is also involved in the regulation of tumor growth and invasion. A recent in vitro study in human cervical SCC cell lines revealed that knocking down galectin-7 enhances tumor cell invasion and tumor cell viability against paclitaxel-induced apoptosis likely through increasing the matrix metallopeptidase (MMP)-9 expression and activating the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway [152]. However, more studies demonstrated that the expression of MMP-9 is increased by galectin-7 in cervical or ovarian cancer cell lines through the p38 mitogen activated protein kinase signaling pathway or mutant p53, respectively, resulting in increased cell invasion [153,154]. In accord with this earlier study, high expression levels of galectin-7 are found exclusively in high-grade breast carcinomas; in a preclinical mouse model of breast cancer, high expression of galectin-7 significantly increases the ability of cancer cells to metastasize to lung and bone [155].

Galectins in tumor angiogenesis

Galectin-3 is involved in tumor angiogenesis and invasion, as vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C)-mediated nuclear factor kB signaling pathway promotes invasion of cervical cancer cells via VEGF-C–enhanced interaction between VEGF receptor-3 and galectin-3 [156]. Moreover, the cleavage of galectin-3 and its subsequent release into the tumor microenvironment leads to breast cancer angiogenesis and progression as supported by the findings with BT-549-H(64) cells, in which galectin-3 increases chemotaxis, invasion and cancer cell–endothelial cell interactions resulting in angiogenesis and 3D morphogenesis. It is suggested that this in vitro angiogenic activity of galectin-3 is related to its ability to induce the migration of endothelial cells [157]. An in vivo study in immunocompromised mice transplanted with human breast cancer cells that overexpress galectin-3 showed increased density of capillaries surrounding the tumors, supporting that galectin-3 secreted by tumor cells induces angiogenesis [158].

In addition, endothelial cells also express several galectins (-1, -3, -8, and -9) that may regulate tumor angiogenesis. For example, galectin-9 splice variants are expressed by endothelial cells, and their expression is regulated during endothelial cell activation. It is suggested that galectin-9 is possibly involved in attracting various immune cells (e.g. dendritic cells, DCs), which release angiogenic growth factors like VEGF, and its altered expression in the endothelium may interfere with a proper anti-tumor immune response [146]. Additional data that has started to emerge on the role of galectins in tumor angiogenesis is reviewed elsewhere [15].

Galectins in tumor immune tolerance

Studies published to date mainly address the involvement of galectin-1 in tumor immune escape. Galectin-1 is involved in CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cell [104] and tolerogenic DC activation, which may contribute to immune escape of tumor cells [159]. Th1 cells are important in anti-tumor immune responses [160] in all cancer types, and galectin-1 induces the selective apoptosis of Th1, Th17, and Tc lymphocytes in mice [161] and humans [25]. Of note, anti–galectin-1 antibody treatment in combination with cell therapy in a cervical cancer mouse model is more effective than the treatment with tumor infiltrating lymphocytes alone [162]. This shows that inhibition of galectin-1 results in decreased immune escape of tumor cells. In addition, galectin-1 silencing in a breast cancer mouse model results in a marked reduction in tumor growth and lung metastases [104]. These results suggest that galectin-1 blockade may be a good therapeutic approach, and further aspects on the roles of galectin-1 in tumor formation and progression are reviewed elsewhere [163].

Extracellular galectin-3 and galectin-7 induces apoptosis of T cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells after binding to cell surface glycoconjugate receptors through carbohydrate-dependent interactions [154,164]. In the case of galectin-3, CD7 and CD29 are identified as its apoptosis-inducing receptors. Furthermore, galectin-3–negative cell lines are significantly more sensitive to exogenous galectin-3 than those expressing this lectin. This suggests crosstalk between the anti-apoptotic activity of intracellular galectin-3 and the pro-apoptotic activity of extracellular galectin-3, providing a new insight for the immune escape mechanisms of cancer cells.

Galectin-9 has immunosuppressive activity similar to galectin-1 [146]; however, its role in tumor immune escape remains largely unexplored. Galectin-9 suppresses Th17 cell differentiation and induces the apoptosis of Th1 and Tc cells, while it enhances CD4+CD25+Treg cell differentiation, suggesting immunosuppressive functions of this lectin. On the other hand, galectin-9 was shown to induce the expansion of DCs and the subsequent potentiation of natural killer (NK) and Tc cell–mediated antitumor immunity in melanoma and sarcoma models, respectively, showing that galectin-9 may have various effects on immune escape [146].

Galectins implicated as blood biomarkers of tumors

A few studies have focused on determining the concentrations of certain galectins (-1, -2, -3, -4, -8, -9) [159,165,166] or galectin ligands [167] in the sera of healthy people and cancer patients. The serum concentrations of galectin-2, -3, -4, and -8 were up to 31-fold higher in patients with breast cancer than in controls, in particular those with metastasis [166]. It is important, since the presence of galectin-3 promotes cancer cell-endothelium adhesion in vitro via the interaction with the T antigen on cancer-associated mucin 1. In addition, galectin-2, -4, and -8 induce endothelial secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in vitro, leading to the expression of endothelial cell surface adhesion molecules, and consequently increase cancer-endothelial adhesion and endothelial tube formation [159].

Serum from breast cancer patients also contains an almost two-fold higher concentration of galectin-1 ligand glycoproteins [167]. The most abundant ones are α-2-macroglobulin, IgM and haptoglobin. In accordance, galectin-1–bound and nonbound haptoglobin uptake was also analyzed, and a dramatic difference was found in intracellular targeting, with the galectin-1 non-binding fraction targeted into lysosomes, while the galectin-1 binding fraction targeted into larger, galectin-1–positive granules. This suggests a major regulatory step in the scavenging of hemoglobin by haptoglobin, which can be altered in cancer [167].

Galectin-3 concentrations in urine of various (e.g. breast, cervical, and ovarian) cancer patients and healthy controls showed a strong correlation between the stages of the disease and galectin-3 concentration [168].

GALECTINS IN PREGNANCY

Pregnancy poses a substantial challenge to the maternal immune system. The semi-allogeneic fetus, placenta and chorioamniotic membranes continuously interact with maternal immune cells in the uterus, which is an immune privileged site [169], and those in the maternal circulation [170]. During implantation and placentation, there is a continuous immune recognition and modulation of the maternal immune system by trophoblasts at the maternalfetal interface [171-174]. Moreover, there is a continuous deportation of fetal cells and trophoblastic debris into the maternal circulation, which leads to microchimerism and an increase in systemic inflammation in the mother during pregnancy [175-179]. Therefore, normal pregnancy is associated with a mild inflammatory state, especially by neutrophils of the innate immune system [180,181]. This is significantly pronounced in preeclampsia, where the activation state of neutrophils is higher than in sepsis [182,183]. Overtly activated neutrophils are also implicated in recurrent fetal loss or bacterially induced abortions [181]. It was also revealed that other great obstetrical syndromes (e.g. intrauterine growth restriction [IUGR] and preterm labor) are also associated with various changes in the phenotypes as well as the behavior of maternal peripheral blood leukocytes and systemic inflammation [183-186]. Since several galectins are expressed at the maternal-fetal interface, the site of contact between maternal and fetal cells that varies among different species [171,187-190], they are proposed to promote maternal-fetal immune tolerance and regulate local and systemic inflammation and infection[10,16,17,26,27]. Indeed, changes in the expression of galectins [23,32-38] have been reported in the great obstetrical syndromes (e.g. preterm labor, preeclampsia) [191], which are related to local and/or systemic inflammation and infection, and are responsible for most perinatal mortality and morbidity [192-205].

Galectin expression at the maternal-fetal interface in normal pregnancy

The human maternal-fetal interfaces dynamically change during gestation [190]. First, the syncytiotrophoblast is in direct contact with maternal cells in the decidua for a few days post-implantation and then with cells in the intervillous space. The latter is also the site of the interaction between the syncytiotrophoblast and maternal blood cells by the end of the first trimester, while invasive extravillous cytotrophoblasts in the placental bed and trophoblasts in the chorion laeve come into contact with maternal cells in the decidua [190]. In this dynamic context, the expression of several galectins is also spatio-temporally regulated during development (Fig. 3) [8]. Galectin-1, -3, and -9 are broadly expressed during human and mouse embryogenesis, suggesting that they may play a role in embryo development in mammals [8]. Despite that, galectin-1 or galectin-3 knock out (KO) mice are viable [206], possibly due to the redundancy in galectin functions [8]. In addition, galectin-1, -3, -8, -9, -13, -14, and -16 are also strongly expressed at the maternal-fetal interface in various mammals, some in a developmentally regulated fashion [16,18,19,21,23,27,32-34,39].

Physiological aspects of galectins at the maternal-fetal interface. The figure represents multiple roles of galectins in implantation, angiogenesis, maternal-fetal immune tolerance and trophoblast invasion. (A) Embryo implantation. (B) Formation of primary villi by proliferative cytotrophoblasts. (C) Formation of tertiary villi, placental angiogenesis, extravillous trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodeling. AE, amniotic epithelium; CCT, cell column trophoblast; DC, dendritic cell; DF, decidual fibroblast; EB, embryoblast; EC, endothelial cell; ECM, extracellular matrix; EM, extraembryonic mesoderm; eCTB, endovascular cytotrophoblast; GC, giant cell; ICM, inner cell mass, iCTB, interstitial cytotrophoblast; LUE, luminal uterine epithelium; L, lacunae; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; NK, natural killer; pF, placental fibroblast; PS, primitive syncytium; pV, placental vessel; SA, spiral artery; S, syncytium; SMC, smooth muscle cell; TE, trophectoderm; UG, uterine gland; uNK, uterine NK cell; UV, uterine vessel; vCTB, villous cytotrophoblast. Cartoons are adapted from Knofler and Pollheimer. Front Genet 2013; 4: 190, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License [217].

For example, galectin-1 expression is strong in the differentiated syncytiotrophoblast but not in the cytotrophoblast during first and third trimesters [19,207,208], and its expression in the extravillous trophoblast is developmentally regulated during the first-trimester [19,209]. This latter phenomenon is also true for galectin-3, which also localizes to villous cytotrophoblasts [19,208]. Galectin-4 has weaker placental expression [27], which is down-regulated during trophoblast differentiation in rats [210]. Galectin-8 has expression in villous and extravillous trophoblasts [39], while galectin-9 is mainly located in the decidua [16]. RNA and protein evidence have shown that galectins in the chromosome 19 cluster (-13, -14, -16, and -17) are predominantly expressed by the syncytiotrophoblast but not by the underlying cytotrophoblasts [27,28,31,33,46,58]. This is supported by galectin-13 immunolocalization to the multinucleated luminal trophoblasts within converted decidual spiral arterioles in the first trimester [28]. A recent study demonstrated that the expression of galectin-13, -14, and -16 is related to the differentiation and syncytialization of the villous trophoblast [72], which is important in the production of placental hormones and immune proteins to control fetal development and immune tolerance [189,211,212]. In vitro assays demonstrated that the expression of these galectins is related to syncytium formation induced by cAMP [72]. Interestingly, the promoter evolution and the insertion of a primate-specific transposable element into the 5’ untranslated region of an ancestral galectin gene introduced several binding sites for transcription factors fundamental in syncytiotrophoblastic gene expression, leading to the gain of placental expression of these chromosome 19 cluster galectins [72,213]. Of note, DNA methylation also regulates the developmental expression of these genes [72] similar to other galectins [214]. Of interest, galectin-1, -7, -9, -13, -14, -16, and -17 are also expressed in the chorioamniotic membranes, but the developmental aspects of their regulation at this site have not yet been revealed [16,27,34,37,38].

Galectins in embryo implantation

Embryonic implantation can be considered a pro-inflammatory response in the decidua, which involves the chemotaxis of leukocytes and their active participation in the regulation of implantation via secreted immune and angiogenic factors [215-218]. Decidual cell-derived factors also have a key role in implantation [219]. Of importance, several galectins are expressed by the uterine endometrium and decidua in mammals and are strictly regulated by sex steroids [18,22,220-222]. The peak expression of these galectins coincides with the implantation time window; therefore, their possible roles in blastocyst attachment and in the regulation of immune cell functions during implantation have been implicated (Fig. 3) [18,21,22].

For example, a temporal expression change of galectin-1, dependent on estrogen and progesterone, has been observed during the estrus cycle in mice [10,18]. In humans, the expression of galectin-1, -2, -3, -4, -8, -9, and -12 is described in the endometrium [21,22,98,113,223-225] where galectin-1 and galectin-3 are highly expressed during the implantation time window [22,221]. Galectin-3 expression is increased in glandular epithelial cells in the secretory phase, while galectin-1 expression is increased in stromal cells in the late secretory phase and further increased in the decidua [22]. Interestingly, galectin-1 is also expressed in the trophectoderm and inner cell mass of human pre-implantation stage embryos, where it may be involved in the attachment to the uterine epithelium [226]. In spite of the identification of galectin-3 in trophoblasts, its role in implantation has not been well defined.

Data in humans and mice support that galectin-9 is also involved in implantation. In mouse models, galectin-9 is associated with cell-to-cell interactions and the establishment of an immuno-privileged local environment for implantation and early fetal development as well as the mediation of decidual cell migration and chemotaxis [223]. In humans, galectin-9 is expressed by the endometrial glandular epithelial cells during the implantation time window as well as by the human decidua during early pregnancy [21]. Electron microscopy clarified its localization on the apical projections of the human endometrial epithelium called uterodomes [223], which are membrane projections that exclusively feature the receptive endometrium during the implantation time window. The contribution of galectin-9 to the development of pregnancy is supported by the observation that normal pregnancy and cases of spontaneous abortions differ significantly in terms of endometrial galectin-9 splice variant profiles in both mice and humans [227].

Galectins in trophoblast invasion

A growing body of evidence suggests that human galectins play key roles in placentation events beyond implantation. For example, galectin-1, -3, and -8 are expressed in the extravillous trophoblast in the first trimester [19,39] throughout the invasive pathway of trophoblast differentiation [212,217,228]. These galectins are expressed in extravillous trophoblast cell columns, where they actively deposit extracellular matrix and can bind to major structural glycans of the placental bed (e.g. fibronectin and laminin) [8,19,39,229] Thus, galectin-1, -3, and -8 may play a role in the organization of the extracellular matrix and the modulation of cell adhesion in the cell columns [19,39]. In addition, galectin-1 and -3 may have a role in the regulation of the extravillous trophoblast cell cycle since they are absent from the differentiated, nonproliferating, interstitially migrating, highly invasive cytotrophoblasts (Fig. 3) [19].

Not only the expression pattern of galectin-1 in the first trimester placenta but also the findings that blocking galectin-1 substantially abrogates migration of primary trophoblasts and HTR8/SVneo cells cultured in matrige [l19,209] suggest that galectin-1 modulates the invasive pathway of trophoblast differentiation and enhances trophoblast invasiveness. Extravillous trophoblastic galectin-3 [19,208] may interact between cell and extracellular matrix components, modulating adhesive interactions and immune reactions as observed in a murine model [230].

In the case of galectin-13 (PP13), a different mechanism is proposed to promote trophoblast invasion [28]. Galectin-13 is secreted by the syncytiotrophoblast to the maternal circulation, from where it is transferred into the decidua in the first trimester, coinciding with the time of early trophoblast invasion. Interestingly, galectin-13 forms crystal-like aggregates in the decidua, where it attracts, activates and kills maternal immune cells, diverting them from spiral arterioles and invading trophoblasts [28]. In this manner, PP13 may serve to establish a decoy inflammatory response, sequestering maternal immune cells away from the site of extravillous trophoblast spiral artery modification.

Galectins in maternal-fetal immune tolerance

In eutherian mammals multiple immune mechanisms exist which support the establishment and maintenance of immunological privilege in the pregnant uterus, as well as antigen-specific, local and systemic maternal-fetal tolerance [10,26,27,171-174,192]. These mechanisms are strongly affected by the type of placentation and the interactions between fetal trophoblasts and maternal immune cells at the maternal-fetal interfaces [171,187,189]. In this regard, it is important to note that galectins are also expressed by maternal immune cells, which infiltrate the decidua and play key roles in mammalian pregnancies (Fig. 3) [20,25,51,70,231].

For example, galectin-1 is strongly expressed by uterine natural killer (uNK) cells compared to peripheral blood NK cells [20]. These CD56+galectin-1+uNK cells comprise ~70% of maternal leukocytes at the implantation site, promote angiogenesis and trophoblast invasion [20,171] and are pivotal for the maternal adaptation to pregnancy [232]. Galectin-1, secreted by human uNK cells, induces apoptosis of activated decidual T cells [25], which is supported by data indicating that galectin-1 can selectively induce apoptosis of Th1 and Th17 cells [25,63] and contribute to maternal immune-tolerance to the semi-allogeneic fetus [10,25,26]. In addition, galectin-1 is among the immunosuppressive molecules secreted by villous trophoblasts, which were identified by a proteomics study and found to inhibit T lymphocyte proliferation and adaptive immune responses [69]. The villous trophoblast secretes other galectins, expressed from the chromosome 19 galectin cluster (-13, -14, and -16), which induce the apoptosis of activated T cells, and thus, are assumed to exert special homeostatic and immunobiological functions at the maternalfetal interface [16,27].

As in vivo evidence for the pivotal functions of human galectin-1, a proteomics study identified it to be down-regulated in villous placenta in early pregnancy loss, reflecting abnormalities in the support for the maintenance of pregnancy [23]. Other in vivo evidence comes from a mouse model of stress-induced fetal loss in which the decidual expression of galectin-1 decreased, and these mice, similar to galectin-1 KO mice, had a higher rate of fetal loss in allogeneic pregnancies [10]. This effect was reversed by the administration of recombinant galectin-1 and also by progesterone treatment, supporting the progesterone-dependent regulation of decidual galectin-1 expression. Galectin-1 treatment also prevents the drop in progesterone and progesteroneinduced blocking factor serum concentrations in stressed animals, suggesting a synergistic effect of galectin-1 and progesterone in pregnancy maintenance [10]. It was also elucidated that galectin-1 exerts its immune modulatory effect through the induction of tolerogenic DCs, which in turn trigger the expansion of interleukin-10 expressing CD4+CD25+Treg cells in vivo [10]. Subsequently, it was determined that Treg cells, which normally expand during pregnancy and suppress the maternal allogeneic response directed against the fetus [187], also overexpress galectin-10, which has an important role in suppressive functions [70,231].

The galectin-9/TIM-3 (T-cell immunoglobulin domain and the mucin domain 3) pathway has been recognized as central in the regulation of Th1 immunity and tolerance induction [233,234]. Very recently, galectin-9 was also implicated in the regulation of uNK cell function and the maintenance of normal pregnancy [235] as galectin-9, secreted by human trophoblast cells, induces the transformation of peripheral NK cells into uNK-like cells via the interaction with TIM-3. In addition, a decreased number of TIM-3+uNK cells was detected in human miscarriages and abortion-prone murine models, and a Th2/Th1 imbalance was detected in TIM-3+uNK cells in human and mouse miscarriages, suggesting the importance of the galectin-9/TIM-3 pathway [235]. Moreover, Treg cells increase their galectin-9 expression with advancing gestational age in accord with the increasing galectin-9 concentrations in maternal blood, suggesting that galectin-9 expressing Treg cells may have important roles in the maintenance of pregnancy [236].

Galectins in placental angiogenesis

Aside from modulating the immune system and trophoblast invasion, human galectins have been implicated in key roles in angiogenesis (Fig. 3). This is not surprising in light of the pivotal role of galectin-glycan interactions in angiogenesis [237] and the angiostimulatory roles of several galectins reviewed elsewhere [14]. The most studied galectin, with respect to placental angiogenesis, is galectin-1. When this lectin is added exogeneously in a rodent model of reduced angiogenesis, it enhances the production of pro-angiogenic factors (e.g. angiogenin, heparin-binding epidermal growth factor, and fibroblast growth factor-basic) and matrix metallopeptidases (MMP-3, MMP-8, and MMP-9) to promote normal vascular development, to rescue implantation and to support healthy placentation [238]. Galectin-1 acts via the NRP-1–VEGF–VEGF-R2 signaling pathway [239,240], which is important in promoting angiogenesis during implantation, decidualization and placentation [241,242]. Galectin-1 binding to neuropilin-1 promotes VEGF–VEGF-R2 interactions, and consequently, endothelial cell migration and adhesion [239,241,243], and these effects can be blocked by an NRP-1 neutralizing antibody, which inhibits VEGF–VEGF-R2 signaling [238,240].

Although several other galectins (-3, -8, and -9) have been implicated in angiogenesis and endothelial cell biology [14], their involvement in placental angiogenesis has not yet been elucidated. The effect of galectin-13 has recently been tested on rat vasculature, and it was found that recombinant galectin-13 reduces blood pressure and increases utero-placental perfusion in vivo, while it promotes vasodilation in isolated arteries in vitro [244,245].

Galectins in local inflammation in the womb

Term parturition is characterized by local pro-inflammatory changes in the decidua and chorioamnion, which play fundamental roles in the initiation of labor and myometrial contractions [37,246-249]. Evidence from microarray studies have shown that galectins may also play a role in pathways leading to term labor as galectin-7 is up-regulated in the amnion in oxytocin-induced labor, and galectin-9 is down-regulated in the chorion at the site of rupture (Fig. 4) [37].

Galectin expression at the maternal-fetal interface. The figure represents the maternal-fetal interfaces where maternal and fetal cells appose each other from the end of the first trimester of human pregnancy. The villous syncytiotrophoblast (depicted with gold) is bathed in maternal blood, whereas invasive extravillous trophoblasts in the placental bed (depicted in red) and chorionic trophoblasts in the fetal membranes (depicted in red) are in contact with maternal cells in the decidua (depicted in dark blue). The differential expression of galectins is depicted according to the interface where observed in normal pregnancy and in pregnancy complications. Sy., syndrome, Cartoon was adapted from Than et al. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2012; 23: 23-31, with permission of Elsevier [16].

Preterm parturition is a syndrome that has many etiologies, predominantly those associated with intra-amniotic infection and inflammation [193,205,250]. The pathways initiated in preterm parturition are different from those in term labor, whereas the terminal pathway of cervical effacement and dilatation, choriodecidual, as well as myometrial activation, are shared between the two [193,205,246,250]. Interestingly, proteomics studies show that galectin-1 is upregulated in the fetal membranes in preterm parturition [38], reflecting heightened local inflammation.

Preterm premature rupture of the membranes (PPROM) is a syndrome in which approximately 32%–75% of the cases are associated with microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity [193,195,196]. To date, only galectin-1 expression has been studied in PPROM using detailed gene and protein expression profiling [34]; it is increased in the chorioamniotic membranes in patients with histologic chorioamnionitis, but not in those without this condition. Galectin-1 expression is increased [34] in a temporal and spatial fashion in amnion epithelial cells, maternal neutrophils and chorioamniotic macrophages and myofibroblasts [251] with advancing inflammation. Since galectin-1 is associated with the up-regulation of genes encoding for MMPs in DCs [252], it has been proposed that the overexpression of galectin-1 in the chorioamniotic membranes may be the link between inflammation, tissue remodeling, and membrane weakening, which may contribute to the membrane rupture [34]. Moreover, the increased expression of galectin-1 by chorioamniotic macrophages upon inflammation suggests a role for galectin-1 in the active barrier functions of the membranes, protecting the fetus from bacterial infection and promoting the recognition and phagocytic removal of invading maternal neutrophils [34]. This hypothesis is supported by findings that (1) activated macrophages are present in the fetal membranes in association with fetal inflammatory response upon infection [253-255], (2) the chorioamniotic membranes have antimicrobial properties [256], (3) galectin-1 expression is up-regulated in activated macrophages [257] where it regulates macrophage effector functions [258], (4) galectin-1 decreases macrophage inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced NO metabolism [259], and (5) it regulates the cell surface expression of FcγRI [258].

Galectins in inflammatory conditions in the neonate

Due to galectins’ roles in immune responses, their relevant roles in term and preterm parturition in the neonate have also been investigated, mainly regarding galectin-1 and galectin-3 (Fig. 4) [260-262].

In term parturition, in spite of the physiological systemic inflammation in the mother at the time of normal delivery, cord blood plasma contains more galectin-3 than maternal plasma, regardless of the delivery mode [262]. In addition, cord blood neutrophils show priming in comparison to maternal neutrophils by responding to galectin-3 with reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, suggesting that inflammatory stimuli associated with labor promotes neutrophils to develop a reactive phenotype with extensive priming features [262]. Indeed, when cord blood leukocytes are stimulated by invasive bacteria, there is an induction of galectin-3 expression, suggesting its importance for innate immunity in the neonate [260]. Although galectin-1 is also expressed in cord blood, lymphocytes expressing galectin-1 were not determined to have a major role in immune reactivity in cord blood [263].

In preterm parturition, the earlier preterm birth occurs, the higher the rate of intra-amniotic infection and inflammation [193]. Since 5%–13% of pregnancies are affected by preterm parturition [194], the resulting severe complications (i.e. intraventricular hemorrhage, cystic periventricular leukomalacia, bronchopulmonary dysplasia [BPD], and cerebral palsy) have disastrous short-term and life-long impacts on the neonate, and the healthcare and social impacts are immense [193,205]. In regard to these, galectin-3 concentrations are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of infants suffering from birth asphyxia, and even higher in those with abnormal outcomes [261]. Since galectin-3 is produced by activated microglia/macrophages and activates NADPH oxidase, leading to neurotoxic production of ROS and contributing to hypoxic brain injury in an animal model [264], it has been proposed to serve as a marker for abnormal outcomes [261]. In addition, in a small preliminary study, galectin-3 concentrations in tracheal aspirates of premature infants tended to be elevated in the first week of life in those who later developed BPD (Staretz et al., personal communication).

IUGR is one of the most heterogeneous syndromes in obstetrics; it is associated with fetal malformations and chromosomal abnormalities, as well as maternal autoimmune disorders and placental dysfunction resulting from poor implantation, making the understanding of an IUGR fetus a challenge. In addition, neonates may be small-for-gestational age (SGA) due to a normal condition in short-stature couples [265]. Of interest, a recent report showed that galectin-3 concentrations in cord blood have a positive correlation with gestational age, and SGA neonates have higher concentrations of galectin-3 than those that are appropriate for gestational age [260], which may be a sign of an inflammatory condition.

Galectins in preeclampsia, a systemic inflammatory state

Based on the above data, it is not surprising that galectins have been implicated in the development of preeclampsia, a syndrome with impaired trophoblast invasion, an anti-angiogenic state and an exaggerated maternal systemic immune response [190,266]. Preeclampsia is a severe complication of pregnancy, which affects 5%–7% of pregnant women and is a leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality [267,268]. It also confers a high risk to the mother and fetus for metabolic and cardiovascular diseases later in life [269-272]. Preeclampsia is a syndrome with a spectrum of phenotypes, which may present at various gestational ages, with different degrees of severity at clinical onset, and also with or without the involvement of the fetus [272-274].

It is a multi-stage disease that has placental origins [190,275-277] due to the failure of extravillous trophoblast invasion into the uterine tissues [278,279] and impaired villous trophoblastic syncytialization [72,280,281]. Subsequent rheological changes in uterine blood flow, metabolic changes, and ischemic stress of the villous placenta lead to the liberation of anti-angiogenic molecules, highly inflammatory placental debris, and cell-free fetal DNA that may also be pro-inflammatory and cause an exaggerated maternal systemic inflammatory response, anti-angiogenic conditions and end-organ damage [179,181,190,192,271,275-277,282-291]. Other, less severe pathologies are also implicated that result in the terminal pathway of systemic inflammation and an anti-angiogenic state [292]. Importantly, several members of the galectin family have been implicated in the development of various stages of this syndrome (Fig. 4).

Impaired extravillous trophoblast invasion

Indirect evidence of galectin involvement is the up-regulation of galectin-1 and -3 in the extravillous trophoblasts in the placental bed during preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome [38,158], which is associated with the failure of extravillous trophoblast invasion [32]. It was also observed that low galectin-13 expression is associated with deficient trophoblast invasion, failure of spiral arteriole conversion, and the development of preeclampsia [28].

Impaired villous trophoblastic syncytialization

Galectin-13 and galectin-14 mRNA expression is decreased in the syncytiotrophoblast in preeclampsia associated with or without HELLP syndrome at the time of clinical onset, predominantly in the early-onset forms [28,33,72]. Importantly, decreased galectin-13 mRNA expression can be detected as early as the first trimester in laser captured specimens of chorionic villous trophoblasts as well as decreased galectin-13 protein and mRNA concentrations in first trimester maternal serum sampled from patients destined to develop preeclampsia [36]. This phenomenon possibly reflects abnormal villous trophoblast syncytialization starting from early pregnancy and may be one of the earliest placental indicators for the subsequent development of preeclampsia. A recent study [72] revealed that GCM1 and ESRRG, two transcription factors that regulate villous trophoblastic syncytialization and metabolic functions, are down-regulated in the placenta in preeclampsia. Functional and evolutionary evidence also implicates these two factors in regulating trophoblastic expression of chromosome 19 galectin cluster genes. This is supported by the observation of decreased GCM1-mediated trophoblast fusion in impaired galectin gene expression in preeclampsia [72]. Furthermore, the differential methylation of LGALS13 and LGALS14 is also found in the villous trophoblast in preterm preeclampsia, suggesting that potential additional disease-mechanisms may account for the trophoblastic pathology in preterm preeclampsia [72].

Villous placental stress

Galectin-1 and -8 are overexpressed in the villous trophoblast in preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome [32,35], where increased placental stress occurs preceding exaggerated maternal systemic inflammation [275,276,290,293,294]. It is possible that galectins may function as “alarmins” in this condition [12,35]. Alarmins are endogenous danger signals secreted by activated cells via non-classical pathways or released from necrotic cells, which signal tissue damage and contribute to the activation and/or resolution of immune responses [66]. Galectin-13 may also be considered a placental alarmin since it is excessively secreted or shed from the syncytiotrophoblast at the time of the clinical onset of preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome [33,64]. Interestingly, the syncytiotrophoblast microvillous membrane and microvesicles, which are shed from the syncytiotrophoblast, stain strongly for galectin-13, suggesting that the increased release of galectin-13–positive microvesicles from the syncytiotrophoblast may lead to elevated maternal serum galectin-13 concentrations when the clinical symptoms appear [33,46].

Anti-angiogenesis

Placental and maternal blood galectin-1 expression is downregulated in patients with early-onset preeclampsia, and Lgals1 KO mice exhibit preeclampsia-like symptoms, probably due to the inhibition of pro-angiogenic effects of galectin-1 [238]. Moreover, blocking galectin-1–mediated angiogenesis with anginex, a synthetic peptide, also promotes preeclampsia-like symptoms in mice and inhibits human extravillous trophoblast functions in vitro [238,295].

Maternal systemic inflammation

The number of galectin-1–expressing NK cells and Treg cells is decreased in preeclampsia [51,296,297], which may reflect a failure of immune tolerance in this syndrome [298]. Recently, the involvement of galectin-9 and its TIM-3 ligand has been implicated in maternal systemic inflammation in preeclampsia [299]. In this regard, decreased TIM-3 expression by T cells, cytotoxic T cells, NK cells, and CD56dim NK cells, as well as increased frequency of galectin-9+peripheral lymphocytes, is detected in women with early-onset preeclampsia, suggesting that the impairment of the galectin-9/TIM-3 pathway can result in an enhanced systemic inflammatory response including the activation of Th1 lymphocytes in preeclampsia [299].

Galectins implicated as maternal blood biomarkers in obstetrical syndromes

Due to the dysregulation of some galectins at the maternal-fetal interface and in maternal blood in various obstetrical syndromes, investigations have been expanded on their possible value as diagnostic, predictive and prognostic biomarkers of these pregnancy complications. Most data is available for galectin-13, also known as PP13, which has been widely investigated by international collaborative studies (Fig. 4) [41-50,58]. The changes in the expression patterns of galectin-13 in the placenta during gestation in normal and preeclamptic pregnancies, the fact that galectin-13 is expressed only in the placenta [27], and it is not detected in non-pregnant patients (Madar-Shapiro et al., personal communication), make this galectin a suitable and promising first trimester maternal blood biomarker for the prediction of preterm preeclampsia. In addition, genetic studies found certain single nucleotide polymorphisms, including an exonic variant(221delT) in the LGALS13 gene, which may increase the risk for preterm labor and preeclampsia [300]. Recent advancement in the field has also facilitated the study of the potential use of this galectin as a therapeutic drug for preeclampsia [244,245]. The utilization of other galectins as biomarkers has recently been started.

In the first trimester of pregnancy, there is a lower PP13 mRNA content in maternal blood in preeclampsia compared to controls [301,302]; however, the predictive value of the detected maternal blood PP13 mRNA species is currently limited due to the varying and low amounts of trophoblastic mRNA reaching the maternal circulation. Much more promising results were derived from studies on maternal blood PP13 concentrations in the first trimester for the prediction of preeclampsia, which were analyzed by a recent meta-analysis [303]. The results were pooled from 19 studies on singleton pregnancies, which were included in prospective or nested case-control studies or fully prospective studies in which a total of 16,153 pregnant women were tested for PP13 between 6 and 14 weeks of gestation [42-48,50,58,304-313]. For all cases of preeclampsia, the mean detection rate (DR) for predicting preeclampsia was 47% (95% confidence interval [CI], 43 to 65) at a 10% false-positive rate (FPR). For preterm preeclampsia, the DR was 66% (95% CI, 48 to 78); for early-onset preeclampsia, the DR was 83% (95% CI, 25 to 100). For all cases of preeclampsia, the positive likelihood ratio (LR) [sensitivity/(1-specificity)] was 5.82, while the negative LR [(1-sensitivity)/specificity] was 0.46. For preterm preeclampsia, both of these indices were better (positive LR, 6.94; negative LR, 0.34).

Of interest, the introduction of maternal ABO blood groups into the prediction model could improve the DRs for preeclampsia, which can be explained by the differential binding of PP13 onto ABO blood group antigen-containing cell surfaces and the varying bioavailability of PP13 in maternal blood depending on the ABO blood type [58]. Moreover, the performance of the first trimester PP13 test could further be improved by the inclusion of PP13 into panels of multiple biomarkers (e.g. ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 [ADAM12], pregnancy associated plasma protein A [PAPP-A], placenta growth factor [PlGF]) [50,314], which is necessitated in light of the syndromic nature of preeclampsia [48,314]. In addition, risk predictions based on combining PP13 and uterine artery Doppler pulsatility index (PI) also showed increased prediction accuracy [42,44,304,306,314-316]. Moreover, the combination of PP13, Doppler PI, and maternal artery stiffness (MAP) increased the DR of preeclampsia to 93% for early-onset preeclampsia and to 86% for all cases of preeclampsia at 10% FPR [49]. This is in line with comprehensive risk algorithms based on combined multi-marker analysis of background risks, MAP, Doppler PI, and a panel of blood biomarkers that can yield much higher predictive value and accuracy than individual markers [306], especially for early-onset (<34 weeks) and preterm (<37 weeks) preeclampsia. Therefore, the introduction of a broad biomarker panel for the evaluation of preeclampsia and other obstetrical syndromes in the first trimester is suggested in order to change antenatal care as formulated by the inverted pyramid model of perinatal evaluation in pregnancy [317].

In the second trimester of pregnancy, galectin-13 does not have much diagnostic or predictive value due to the sharp increase in PP13 maternal blood concentrations in preeclampsia between the first and third trimesters compared to the moderate change in women with normal pregnancy [318]. Interestingly, galectin-1 has recently emerged as a potential preclinical biomarker for preeclampsia since a prospective study detected decreased galectin-1 maternal blood concentrations and placental expression in early-onset preeclampsia compared to normal pregnancy in mid pregnancy [238]. Of note, placental galectin-1 expression is increased in preterm and severe preeclampsia compared to normal pregnancy [35,238].

In the third trimester of pregnancy, galectin-13 may have diagnostic significance for the clinical development of preeclampsia according to a recent meta-analysis [318]. This included eight clinical studies that contained third trimester maternal blood PP13 data from 2750 pregnant women [33,45,46,58,319,320]. Maternal blood PP13 was higher in women who subsequently developed preeclampsia compared to unaffected women. The mean DR at 10% FPR for all preeclampsia cases was 59.4% (95% CI, 49.7 to 64.5), and for preterm preeclampsia was 71.7% (95% CI, 60.3 to 75.3). Interestingly, the DR appeared to be related to the severity of the cases in a given study, showing that the higher the hypertension and proteinuria, the higher the third trimester PP13 in maternal blood. A combined algorithm of PP13, MAP and proteinuria yielded a 95% DR for preterm preeclampsia and 85% for all preeclampsia at 5% FPR. The positive LR for all cases of preeclampsia was 5.94 and the negative LR was 0.45, providing an overall LR of 26.24. The positive LR for preterm preeclampsia was 7.17 and the negative LR was 0.31, providing an overall LR of 37.99. Therefore, the meta-analysis indicates that higher third trimester maternal blood PP13, among women who subsequently developed preeclampsia, reached clinical diagnostic levels [318].

CONCLUSION

Galectins are an evolutionarily ancient family of lectins that have pleiotropic functions in the regulation of key biological processes. Galectins are pivotal in immune responses, angiogenesis, cell migration and invasion, and due to these functions, they have double-edged functions in shared and unique pathways of embryonic and tumor development. Recent advances facilitate the use of galectins as biomarkers in obstetrical syndromes and in various malignancies, and their therapeutic applications are also under investigation.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

We thank Szilvia Szabo, Zsolt Gelencser and Balint Peterfia (Hungarian Academy of Sciences), Krisztian Papp (Eotvos Lorand University), Pat Schoff and Russ Price (Perinatology Research Branch), and Valerie Richardson (Yale University) for their technical assistance and/or art work, and Sara Tipton (Wayne State University) for critical reading of the manuscript. Figs. 1 and 4 were adapted from reference 16 with kind permission from Elsevier. Fig. 3 was adapted from reference 217 under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License and with kind permission from Martin Knofler and Jurgen Pollheimer. Original research conducted by the authors in the topic and the writing of this manuscript was supported, in part, by the Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS); Federal funds from the NICHD under Contract No. HHSN275201300006C; the European Union FP6 Grant “Pregenesys 037244”; the Hungarian OTKA-PD Grant “104398”; and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Momentum Grant “LP2014-7/2014”.