Gastric crystal-storing histiocytosis with concomitant mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma

Article information

Abstract

Crystal-storing histiocytosis (CSH) is a rare entity that is characterized by intrahistiocytic accumulation of crystallized immunoglobulins. CSH is not a malignant process per se, but the majority of CSH cases are associated with underlying lymphoproliferative disorder. Although CSH can occur in a variety of organs, gastric CSH is very rare. We present a localized gastric CSH with concomitant mucosaassociated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, manifesting as an ulcer bleeding in a 56-year-old man. Histologically, the biopsied gastric mucosa demonstrated expansion of the lamina propria by prominent collections of large eosinophilic mononuclear cells containing fibrillary crystalloid inclusions. Immunohistochemical studies revealed that the crystal-storing cells were histiocytes harboring kappa light chain-restricted immunoglobulin crystals. Within the lesion, atypical centrocyte-like cells forming lymphoepithelial lesions were seen, consistent with MALT lymphoma. Since this entity is rare and unfamiliar, difficulties in diagnosis may arise. Particularly, in this case, the lymphomatous area was obscured by florid CSH, making the diagnosis more challenging.

Crystal-storing histiocytosis (CSH) is a rare entity that is characterized by prominent collections of histiocytes with a distinctive intracytoplasmic accumulation of immunoglobulin crystals [1-4]. The name CSH is descriptive and sounds harmless, but up to 90% of cases are associated with an underlying lymphoproliferative or plasma cell disorder, such as multiple myeloma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance [2-4]. That is, CSH is an under-recognized paraneoplastic phenomenon, and the awareness of CSH may help to detect a hidden malignancy. CSH can be overlooked if so subtle, while extensive CSH can obscure a concomitant lymphoma. We herein describe the histologic findings of CSH associated with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma in detail, to be aware of this rare entity and facilitate a proper diagnosis.

CASE REPORT

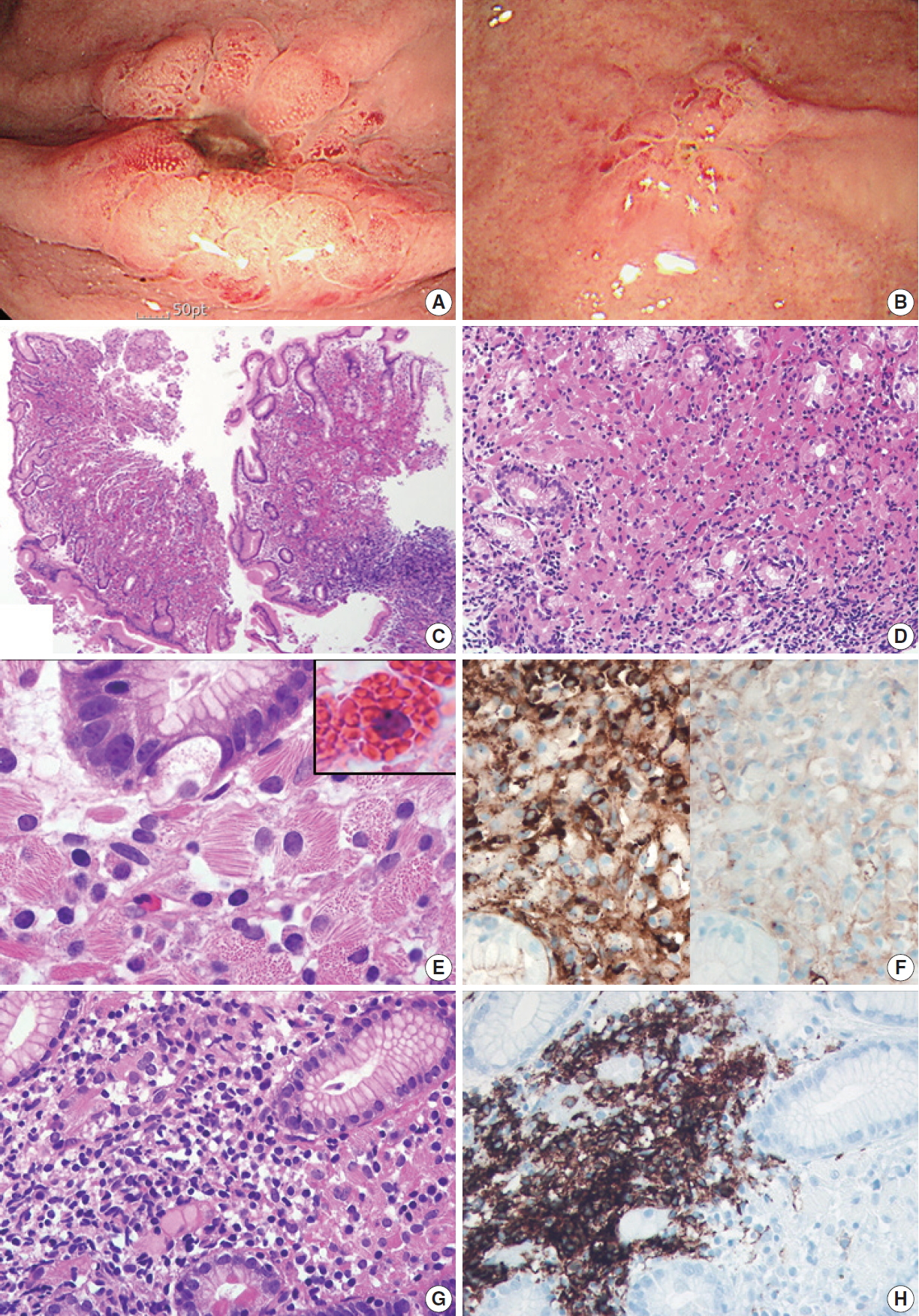

A 79-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with melena and hematemesis lasting for 5 hours. He denied any previous history of gastrointestinal bleeding. His medical history included lacunar infarct, hypertension, and dementia. He was taking Aspirin Protect (100 mg/day). Laboratory test demonstrated anemia (hemoglobin, 9 g/dL; hematocrit, 26.7%), but otherwise normal complete blood counts. Emergency endoscopy and colonoscopy were performed. Colonoscopy showed no bleeding focus. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed a 1 cm-sized active ulcer with an eroded vessel in the high body (Fig. 1A), which was treated with epinephrine injection and argon plasma coagulation. The surrounding mucosa was hyperemic and friable. A flat nodular lesion with irregular margin and discoloration was also seen in the low body (Fig. 1B). Multiple biopsy specimens were obtained from the margin, the surrounding area of the ulcer, and the flat nodular lesion. Microscopically, all biopsy specimens showed marked expansion of the lamina propria by sheets of large mononuclear cells with brightly eosinophilic cytoplasm and eccentric small bland nuclei (Fig. 1C, D). At higher magnification, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm contained fibrillary, needle-like, non-refractile crystalloid inclusions (Fig. 1E). Immunohistochemical studies revealed that these crystal-storing cells were histiocytes harboring kappa light chain-restricted immunoglobulin crystals; they were diffusely positive for CD68 and kappa light chain (Fig. 1F, left), but negative for lambda light chain (Fig. 1F, right), desmin, smooth muscle actin, S100 protein, CD117, CD1a, and cytokeratin. Also, there were multifocal aggregates of atypical lymphocytes and plasma cells, which also showed kappa light chain restriction. Atypical lymphocytes forming lymphoepithelial lesions were CD20-positive B cells (Fig. 1G, H), and the diagnosis of CSH associated with MALT lymphoma was rendered accordingly. It was not easy to identify the lymphoepithelial lesions due to overwhelming accumulation of crystal-storing histiocytes. Helicobacter pylori–like organisms were not observed histologically, and the result of Campylobacter-like organism test was also negative. The patient refused to undergo bone marrow biopsy. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography revealed no lymph node enlargement or organomegaly.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy reveals an active ulcer surrounded by elevated hyperemic mucosa in the high body (A) and another flat erosive lesion showing hypertrophic folds and nodularity in the low body (B). (C, D) Microscopically, all the biopsy specimen demonstrates dense infiltration of large eosinophilic mononuclear cells and lymphocytes, along with remarkable decreases in gastric glands. (E) At higher magnification, infiltrating mononuclear cells are packed with eosinophilic, fibrillary, needle-like crystalloid inclusions displacing nuclei, which are different from Mott cells that have grape-like intracytoplasmic spherical inclusions (inset). (F) Immunohistochemically, both crystalstoring cells and lymphoplasma cells show kappa light chain restriction: they are positive for kappa (left) and negative for lambda (right) immunostains. (G) Atypical small- to intermediate-sized lymphoid cells infiltrate adjacent gastric glands to form a lymphoepithelial lesion, which are CD20-positive centrocyte-like cells (H).

DISCUSSION

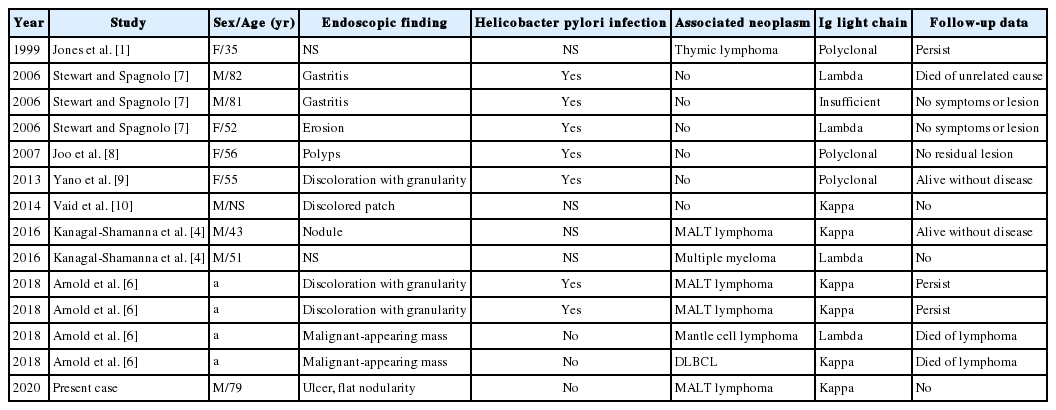

To date, about 130 cases of CSH have been reported in a wide variety of organs, including bone marrow, lymph nodes, liver, spleen, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, kidney, central nervous system, and skin [1-5]. It may present as either localized (a single deposit involving only one organ or site) or generalized (multiple deposits involving more than one organ or site) forms [2]. Localized CSH is more frequent than generalized CSH (about 70% versus 30%) [2-3,5]. The vast majority of the reported CSH cases had underlying lymphoproliferative or plasma cell disorder with monotypic kappa light chain [2-4]. CSH is extremely rare in the stomach, and until now, 14 cases of gastric CSH (including the present one) have been described in the English literature [1,4,6-10]. The detailed clinical and pathological findings of these patients are summarized in Table 1. The 14 patients reported included 8 men and 6 women with a mean age at diagnosis of 61 years (range, 35 to 82 years). There were one generalized (7.1%) and 13 localized (92.9%) forms. Among them, eight patients (57%) had a concomitant or subsequent lymphoplasmacytic malignancy: four MALT lymphomas with kappa-restriction, one mantle cell lymphoma with lambda-restriction, one diffuse large B cell lymphoma with kappa-restriction, one multiple myeloma with lambda-restriction, and one metachronous thymic lymphoma. Five patients (35.7%) had no associated disease except H. pylori infection, and the remaining one patient showed no etiologic condition. Four of the patients who had H. pylori infection alone did not develop other gastric lesion or symptoms during the follow up period [7-9]. Compared to other organs, gastric CSH predominantly manifested as a localized form, and about half of the cases were not related to clonal lymphoproliferative disorders: instead, they were frequently associated with H. pylori–associated gastritis.

Clinical and pathological findings of previously published cases of gastric crystal-storing histiocytosis in the English literature

The differential diagnosis of CSH may include a variety of conditions characterized by collections of large eosinophilic tumor cells (adult rhabdomyoma, granular cell tumor, and oncocytic neoplasms) or histiocytic aggregation (Langerhans cell histiocytosis, fibrous histiocytoma, xanthogranuloma, Gaucher’s disease, malakoplakia, and mycobacterial or fungal infection) [2-4,6]. However, considering the distinctive intracytoplasmic immunoglobulin crystal and gastric location, Russell body gastritis (RBG) may be the most difficult differential diagnosis. RBG is another rare entity characterized by aberrant immunoglobulin deposits in the stomach [11]. Unlike CSH consisting of predominantly histiocytes with crystallized immunoglobulin in the lysosome, RBG is composed of plasma cells with small condensed spherical immunoglobulin surrounded by endoplasmic reticulum membrane (called Mott cells) [12]. Besides histological picture displaying diffuse proliferation of large eosinophilic mononuclear cells in the lamina propria, RBG cases also share similar features, such as frequent kappa light chain restriction of accumulated immunoglobulin (43%) and strong association with H. pylori infection (67%) [11]. There were two cases of RBG related to lymphoplasmacytic neoplasm: one with concomitant MALT lymphoma and another with metachronous multiple myeloma three years after RBG diagnosis [13,14]. However, so far, RBG has been considered a unique inflammatory reaction rather than a paraneoplastic phenomenon. Thus, gastric CSH seems to be more significant than RBG in the aspect of association with lymphoproliferative disorder.

In conclusion, although CSH rarely manifests in the stomach, the recognition of CSH is important to initiate a clinical workup searching for the underlying neoplasm or associated cause. Therefore, once the diagnosis of CSH is rendered, pathologists have to provide prompt notification to the clinician. Sometimes, CSH can be so extensive as to obscure the concomitant neoplasm. Thus, pathologists should be aware of the detailed histological features of CSH to avoid misdiagnosis and also should have a high level of suspicion for the presence of accompanying lymphoproliferative disorder.

Notes

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital with a waiver of informed consent (IRB No. ISPAIK 2020-02-004) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: MJ, NHK. Investigation: MJ. Visualization: MJ, NHK.

Writing—original draft: MJ. Writing—review & editing: MJ, NHK

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding to declare.