The Asian Thyroid Working Group, from 2017 to 2023

Article information

Abstract

The Asian Thyroid Working Group was founded in 2017 at the 12th Asia Oceania Thyroid Association (AOTA) Congress in Busan, Korea. This group activity aims to characterize Asian thyroid nodule practice and establish strict diagnostic criteria for thyroid carcinomas, a reporting system for thyroid fine needle aspiration cytology without the aid of gene panel tests, and new clinical guidelines appropriate to conservative Asian thyroid nodule practice based on scientific evidence obtained from Asian patient cohorts. Asian thyroid nodule practice is usually designed for patient-centered clinical practice, which is based on the Hippocratic Oath, “First do not harm patients,” and an oriental filial piety “Do not harm one’s own body because it is a precious gift from parents,” which is remote from defensive medical practice in the West where physicians, including pathologists, suffer from severe malpractice climate. Furthermore, Asian practice emphasizes the importance of resource management in navigating the overdiagnosis of low-risk thyroid carcinomas. This article summarizes the Asian Thyroid Working Group activities in the past 7 years, from 2017 to 2023, highlighting the diversity of thyroid nodule practice between Asia and the West and the background reasons why Asian clinicians and pathologists modified Western systems significantly.

While universally guided by fundamental principles, the discipline of pathology is inherently influenced by regional variations. Asian pathologists and cytopathologists, despite being educated predominantly through international textbooks written by Western scholars, often find that the ground realities and nuances in their regions necessitate adaptations. Systems like the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytology (TBSRTC) [1], the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of thyroid tumors [2,3], and the American Thyroid Association clinical guidelines [4] are indispensable. Nevertheless, their direct application in Asia occasionally yields outcomes that diverge from Western findings [5-16]. The intersection of these variances traces back to a myriad of intertwined scientific and non-scientific factors.

Population-based factors

Beyond genetic and biological differences, cultural practices and socio-environmental determinants in Asia can greatly influence thyroid pathology outcomes. For instance, dietary iodine intake, prevalent in many Asian diets, can significantly affect thyroid physiology and pathology.

Socio-economic and healthcare infrastructure

Diverse Asian nations, with their distinct historical trajectories, have developed unique healthcare infrastructures. The accessibility and quality of healthcare, including diagnostic facilities, can vary even within countries, let alone between them.

Economic burden of medical care

The juxtaposition of North American and Asian healthcare expenditure strategies underlines more profound socio-economic and policy-driven differences. These variations often dictate clinical decisions, with patient affordability playing a crucial role. Medical expenses vary significantly across countries, with North America typically experiencing higher costs. Immediate surgery is frequently chosen to reduce these expenses. However, in other parts of the world, the approach often leans towards risk stratification for surgery and long-term clinical monitoring, as these tend to be more cost-effective than surgical interventions compared to the United States.

Healthcare insurance variations

Health insurance schemes’ dynamics, influenced by public policies and private market forces, can significantly sway diagnostic and treatment choices.

Medical specialization and density of pathologists

The density of pathologists across countries significantly shapes the landscape of medical practice [17]. The number of pathologists in a country is intrinsically linked to the efficiency and effectiveness of its medical system.

Medico-legal climate and clinical guidelines

The medico-legal environment molds clinical practice considerably. In some countries, clinical practice guidelines are established with a defensive approach due to the potential for physicians to face malpractice lawsuits. While defensive medicine may seem prudent in litigious societies, it can inadvertently lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment, escalating healthcare costs. Conversely, other nations resist such defensive medicine because it escalates societal costs and burdens patients financially [18-20].

Terminological and classificatory nuances

The evolution of medical terminologies and classifications, often reflecting deeper understandings of diseases, underscores the importance of constant knowledge exchange and adaptation among global medical communities. The noninvasive encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (FVPTC) was once classified as a malignant tumor in American thyroid nodule practices. Its prevalence in the West is elevated due to a lower threshold for recognizing papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) nuclear features (Fig. 1) [21,22]. However, this classification was later changed to noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP) [2,23]. In many Asian practices, these are typically observed in benign follicular adenomas (FAs) due to a higher threshold for PTC-type nuclear features (Fig. 1), resulting in a lower prevalence of NIFTP in surgically removed nodules in Asia [2,8,11,12,14-16].

NS from 0 to 3 in encapsulated follicular pattern tumors results in variable benign, borderline, or malignant diagnoses between Asian and Western pathologists. Four illustrations (NS 0–1, NS 1–2, NS 2–3, and NS 3 or more) in encapsulated follicular pattern tumors often result in diverse benign, borderline, or malignant diagnoses among pathologists [5-7]. The two illustrations on the left are FA when noninvasive or FTC when invasive in Asian thyroid practice because those extremely delicate nuclear features are insufficient for PTC-type malignancy. Most Western pathologists accept nuclear features in the three illustrations (NS 1–2, NS 2–3, and NS 3 or more) on the right as positive for PTC-N and call them using the same diagnostic terminology, PTC type nuclear features, regardless of different genetic backgrounds, BRAF or RAS oncogene lineages [1-3,21-23]. Some Asian pathologists distinguish nuclear features in the two illustrations (NS of 2–3 and NS of 3 or more) on the right, either RAS-like FV-PTC or BRAF-like conventional PTC [14,16,35]. NS, nuclear score defined by Nikiforov et al. [2,23]. NS, nuclear scoring; FA, follicular adenoma; FTC, follicular thyroid carcinoma; NIFTP, noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillarylike nuclear features; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; PTC-N, papillary thyroid carcinoma type nuclear features; FV-PTC, follicular variant PTC; RAS, rat sarcoma virus; BRAF, v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B.

Clinical management philosophies

The decision-making algorithms in medicine are based on clinical evidence, patient preferences, physician experiences, and systemic constraints. In Asian clinical practice, a more conservative management approach is typically adopted, emphasizing clinical risk stratification for high-risk indeterminate thyroid nodules, specifically follicular neoplasm (FN) [9-11,13-16]. Conversely, in North America, diagnostic surgery becomes the preferred course when patients cannot afford molecular tests [1,4,9, 10,11,13-15]. Consequently, in the West, indeterminate nodules, categorized as Bethesda III (atypia of undetermined significance [AUS]) and IV (FN), have a high resection rate (RR) of over 50% but a lower risk of malignancy (ROM) of less than 30%. In contrast, most Asian practices show a lower RR of less than 40% for these nodules, with a ROM exceeding 40%, even in the absence of molecular testing [9-11,13-16].

Country-specific approaches

Each country, influenced by its unique medical history, patient demographics, and healthcare policies, carves out its distinct approach to disease management. In Japan, a more conservative approach to management is prevalent [10,11,24-26]. Traditionally, lobectomy is the chosen procedure for low-risk small PTCs measuring 1–2 cm and for slightly larger low-risk PTCs, specifically, those sized less than 4 cm and categorized as T1–2, extrathyroidal extension (Ex) 0–1, N0–1, and M0 [24-26]. This conservative strategy offers notable benefits, most crucially the potential preservation of thyroid function. Such a conservative approach is particularly vital as patients who undergo total thyroidectomy and subsequently experience poorly managed hypothyroidism face severe risks, especially as they age and potentially struggle with proper hormone supplement management. Contrarily, in most other regions of Asia, as well as in North America and Europe, the predominant choice leans towards total thyroidectomy in the past [4,24-27].

Active surveillance vs. surgical intervention

The balance between surgical intervention and observation hinges on the collective experiences of a medical community, patient trust, and the broader healthcare framework. In Japan, over half of the patients with low-risk, small PTCs (less than 10 mm) opt for active surveillance, undergoing clinical follow-ups without surgery once a fine needle aspiration (FNA) confirms the malignancy [4,28-31]. Conversely, in the majority of other nations, FNA is typically not recommended for thyroid nodules that are small and low-risk, especially those under 1 cm [4]. This distinction arises from the fact that once an FNA identifies a nodule as malignant, surgery becomes the frequent choice, leading to potential overtreatment for patients with low-risk, small PTCs [4,14-16].

Grossing techniques for encapsulated follicular pattern thyroid tumors

As medicine advances, so does the need for precision. Nevertheless, precision must be juxtaposed against practicality in the light of resource optimization. Grossing techniques for encapsulated follicular pattern thyroid tumors vary globally. In Western countries, where pathologists often adopt defensive medical practices due to malpractice concerns, there is an emphasis on meticulously sampling the entire tumor capsules [2,15,16,32,33]. As recommended in Western textbooks, this practice has influenced the protocols in certain Asian laboratories, notably in China, Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand [32]. Conversely, Indian, Indonesian and Japanese labs generally select only representative sections, typically fewer than 10 per nodule, adhering to prior textbook guidelines [33,34]. This streamlined approach reduces the number of hematoxylin and eosin sections taken (from more than 20 sections to fewer than 10 per nodule) and conserves both pathologist time and societal resources.

The reasoning behind this more economical approach in India, Indonesia and Japan is multifaceted: (1) Lobectomy is deemed suitable for a range of nodules, from benign (e.g., FA) to borderline tumors (e.g., NIFTP, thyroid tumors of uncertain malignant potential), and even low-risk malignancies (like minimally invasive follicular thyroid carcinoma [FTC] or encapsulated conventional PTC) [4,24-26,33]. (2) Only pronounced, clear invasions carry significant implications for a patient’s prognosis. With this method focused on Sustainable Development Goals, there is virtually no risk of overlooking clinically consequential carcinomas, such as extensively angio-invasive or widely invasive carcinomas [2,3,33]. (3) Conducting exhaustive histological examinations to identify ambiguous invasions can result in the overtreatment of low-risk tumors, such as those termed minimally invasive FTCs or encapsulated FVPTCs (EFVPTCs). (4) Restricting the number of samples (to less than 10 sections) mirrors the clinical guideline of refraining from FNAs on low-risk thyroid nodules smaller than 1 cm. This approach encourages a clinical follow-up, subsequently reducing surgeries for small papillary carcinomas. Moreover, limiting samples can mitigate the unintended identification of questionable capsular invasions and, consequently, the diagnoses of minimally invasive FTCs and EFVPTCs. This, in turn, lessens the likelihood of excessive treatments, like completion thyroidectomy or radioactive iodine abrasion, particularly for very low-risk thyroid tumors with negligible prognostic impact [36-39].

Categorization of cyst fluid only samples

How we classify and interpret diagnostic samples evolves with our understanding of disease processes and the nuances of clinical implications. In past cytological practices, including in the United States, cyst fluid only samples from thyroid FNA cytology were typically categorized as benign. However, current Western practices have moved these samples to the inadequate category due to the substantial risk they pose for false-negative diagnoses and the potential inability to completely exclude cystic PTC [1,14-16]. In contrast, some countries in Asia/Oceania still classify these samples as benign, while European countries might place them in a specific subcategory under the inadequate category. This reclassification in Europe is attributed to the extremely low malignancy risk associated with these samples, which is on par with or even lower than the risk associated with samples in the benign category [9,15,16].

VARIATION IN THYROID NODULE PRACTICES ACROSS REGIONS

In 2002, some members of the Asian Thyroid Working Group observed notable discrepancies between Japanese and American pathologists concerning the classification of encapsulated follicular pattern thyroid tumors [5,6]. The majority of noninvasive encapsulated follicular pattern thyroid nodules exhibiting subtle nuclear atypia consistent with RAS-like tumors (RAS-like dysplasia) were classified as malignant PTCs by American pathologists. In contrast, Japanese pathologists often categorized them as benign FAs or hyperplastic nodules (Fig. 1) [5,6,16,21,22]. This observation was further corroborated by multiple subsequent studies [7,15,21,22]. Following a comprehensive review of 109 cases, which exhibited neither recurrence nor metastasis over an average 14-year follow-up period, the international NIFTP working group reclassified these noninvasive encapsulated follicular pattern tumors in 2016. Previously deemed as malignant (FVPTC), they were redefined as borderline tumors (NIFTP) [23]. Despite this, considerable disparities persist between Asian and Western practices, notably in the prevalence of NIFTP— a statistic that remains higher in the West [2,8,11,12,14-16,22,40-43] compared to Asia [12,14,44-49].

The Asian Thyroid Working Group was inaugurated in 2017 during the 12th Asia Oceania Thyroid Association (AOTA) Congress in Busan, Korea [49,50]. The group’s initial endeavors explored the distinctions between Asian and Western approaches to thyroid nodule management. In the West, FVPTC (often synonymous with RAS-like PTC) represents a significant portion of PTC diagnoses [1-4,12,22,23,37,51]. Consequently, the frequency of the BRAF V600E mutation is somewhat diminished in Western PTC cases, given that EFVPTCs are typically non-BRAF (RAS-like) tumors [40]. Conversely, Asian PTC samples manifest a higher prevalence of the BRAF V600E mutation, largely because EFVPTCs are scarcely identified in Asian thyroid evaluations. A majority of encapsulated follicular pattern tumors with mild RAS-like dysplastic nuclear alterations are designated as benign FA in prevalent Asian practices [6-8,11,14-16,40,41].

This manuscript chronicles the endeavors and discoveries of the Asian Thyroid Working Group from 2017 to 2023, underscoring the nuanced distinctions in thyroid nodule practices between Asia and the West. A comprehensive exploration of these global thyroid nodule practice variances will be the centerpiece of an upcoming textbook titled “Thyroid FNA Cytology, Differential Diagnoses, and Pitfalls: 3rd Edition” [52].

GROUP STUDY INSIGHTS

Asian perspectives on NIFTP [12,44-48]

A noninvasive encapsulated follicular pattern tumor, which exhibited worrisome nuclear features characteristic of PTC (RAS-like dysplasia), was previously categorized as a malignant tumor (FVPTC). This classification was predominant due to the lower threshold set for malignancy based on RAS-like PTC nuclear features in earlier Western thyroid nodule practices [5-8,21-23, 40-45]. This classification was later revised to “NIFTP” and was categorized as a borderline tumor in the 4th edition of the WHO classification [2,23,42,43]. Comprehensive data regarding the global incidence of NIFTP was derived from a thorough review of published studies and collaborative research efforts by members of the Asian Thyroid Working Group. These studies ascertained that the global occurrence of NIFTP is notably less than what was initially anticipated [12,47,48]. Furthermore, the incidence rates of NIFTP in Asia are substantially lower than those observed in North American and European regions. This discrepancy stems from the perception of NIFTP in Asia—it isn’t deemed to necessitate surgical intervention. Instead, a conservative approach that emphasizes risk stratification for surgical interventions is the conventional clinical protocol for managing indeterminate thyroid nodules in Asia [9-11,14-16]. This practice is also influenced by the stringent criteria for identifying PTC-type nuclear features in the region (Fig. 1) [5,6,11,14-16,21,22,40].

Malignant lymphoma in Asian practice [53]

This study analyzed 153 cases of primary thyroid lymphoma (PTL) collected from 10 institutions represented by members of the Asian Thyroid Working Group. The reported prevalence was 0.54% of all malignant thyroid tumors. The breakdown indicated that mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma accounted for 54.9%, while diffuse large B-cell lymphoma represented 38.6%. Ultrasound examination and FNA cytology were the primary preoperative diagnostic tools, with flow cytometry conducted in five institutions. The findings suggest that the prevalence of PTL in non-Western countries is lower than previously reported in other studies.

Oncocytic (Hürthle cell) lesions in Asian practice [54]

Of 42,190 thyroid aspirates, 760 (1.8%) exhibited a predominance of Hürthle cells. These samples were sourced from nine hospitals across six Asian countries. The majority, or 61%, were categorized as “atypia of undetermined significance, Hürthle cell type” (AUS-H); 35% were identified as “follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type” (FN-H); and 4% were classified as “suspicious for malignancy” (SFM). Histologic follow-up was conducted for 288 of these aspirates (equivalent to 38%). Of these, a significant majority (66%) were determined to be benign upon resection, with the most common histologic diagnosis being Hürthle cell adenoma at 28.5%. The ROM for AUS-H, FN-H, and SFM, based on the resected nodules, was 32%, 31%, and 71%, respectively. Meanwhile, the risk of neoplasm was calculated to be 47%, 81%, and 77% for the respective categories.

Medullary (C cell) thyroid carcinoma in Asia practice [55-57]

From 13 hospitals across 8 Asia-Pacific countries, 145 cases of medullary (C cell) thyroid carcinoma (MTC) with accessible FNA slides were gathered for this study. Of these cases, 99 (68.3%) were preliminarily interpreted as either suspicious for MTC (SMTC) or confirmed as MTC. While cytological detection alone for MTC showed limitations, the combined application with auxiliary tests substantially enhanced diagnostic proficiency. The staining techniques employed varied across institutions and included Papanicolaou, hematoxylin-eosin, and Romanowsky methods. Liquid-based cytology was implemented in merely three of the countries. Following a comprehensive review of all cases, the diagnostic rate for MTC or S-MTC rose to 91.7% (133 out of the 145 cases). Based solely on cytomorphologic data, a plausible scoring system has been suggested to ensure optimal diagnostic precision. Additionally, Jung et al. [57] provided an overview of the latest advancements and modifications related to MTC as delineated in the WHO classification.

Capsular invasion study [58]

This investigation assessed interobserver concordance in evaluating capsular invasion among 11 thyroid pathologists from five Asian countries. This was accomplished using 20 cases presented as virtual slides. The levels of agreement for definitive invasive and noninvasive classifications were fair, evidenced by kappa values of 0.578 and 0.404, respectively. However, concordance was poor for cases with ambiguous invasion, as indicated by a kappa value of 0.186. The discrepancies in invasion assessment led to divergent final pathological conclusions. In summary, the research highlighted significant interobserver variability in the assessment of capsular invasion, particularly in FNs where the invasion was debatable.

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma studies [59,60]

PAX8 in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma [59]

PAX8 immunohistochemistry using the MRQ-50 antibody was performed in whole tissue slides (n = 147) or tissue microarray sections (n = 35). The study found PAX8 expression in 54.4% of the cases, significantly lower than those reported in prior studies with the polyclonal antibody. PAX8 expression was positively correlated with an epithelial pattern (63.6% vs. 37.5%) and a coexisting differentiated thyroid carcinoma component (71.6% vs. 44.3%). Pathologists should be aware that PAX8 expression in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) is less than those reported in early studies to avoid misdiagnosis.

Primary and secondary ATCs [60]

This study searched for ATCs in our institutional databases and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Result (SEER) database. The multi-institutional database retrieved 22 primary (de novo) and 23 secondary ATCs (the patient had a history of differentiated thyroid cancer [DTC] or coexisting DTC components at the time of diagnosis). Compared to primary ATCs, secondary ATCs were not statistically different regarding demographics, clinical manifestations, and patient survival. The only clinical discrepancy between the two groups was a significantly larger tumor diameter of the primary ATCs. The prevalence of TERT promoter, PIK3CA, and TP53 mutations was comparable between the two subtypes. In comparison to primary ATCs, however, BRAF mutations were more prevalent (odds ratio [OR], 4.70; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.84 to 7.78), whereas RAS mutations were less frequent (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.21 to 0.85) in secondary tumors.

BRAF-like nuclear features and RAS-like dysplasia [35]

This study examined whether pathologists could distinguish BRAF-like and RAS-like nuclear features morphologically. This analysis suggests that nuclear pseudo-inclusions and high nuclear scores have diagnostic utility as rule-in markers for differentiating PTC with BRAF V600E mutation from benign or borderline follicular tumors with RAS-like mutations. Relaxation of rigid criteria for nuclear features resulted in an overdiagnosis of PTC. Immunostaining or molecular testing for BRAF V600E mutation is a valuable adjunct for cases with high nuclear scores to identify true PTC.

FA with papillary architecture and a proposal for a new borderline tumor, noninvasive encapsulated papillary RAS-like thyroid tumor [61,62]

The term “noninvasive encapsulated papillary RAS-like thyroid tumor (NEPRAS)” was introduced by Ohba et al. in 2019 [61] to describe a noninvasive thyroid tumor characterized by a complete fibrous capsule, a predominantly papillary architecture, and the presence of a RAS mutation, yet exhibiting only subtle nuclear features consistent with PTC (RAS-like dysplasia). This tumor poses a challenge for pathologists as it lies at the intersection between an encapsulated conventional BRAF-like PTC and the FA with papillary architecture, which was recognized as a benign tumor entity in the 5th edition of the WHO classification [2,3].

To address the diagnostic challenge and reduce the psychological impact on patients, the term “NEPRAS” was proposed, echoing the approach taken with the NIFTP terminology as introduced by Nikiforov et al. [23]. Subsequently, Jung et al. [62] documented three additional cases, suggesting that a favorable prognosis could be anticipated following surgical resection of such tumors. This optimism is grounded in the understanding that most encapsulated thyroid tumors, when not invasive, tend to be indolent, mirroring the behavior of FAs regardless of their growth patterns (be it NIFTP in follicular or NEPRAS in papillary patterns) [37,38,63]. However, it is noteworthy that extensive long-term follow-up data on a large patient cohort still needs to be available [62].

RR and ROM of indeterminate (Bethesda III and IV) cytology [13,64-66]

Without molecular tests [13,64]

Increasing evidence shows that clinicians employ different management strategies in their use of TBSRTC. This meta-analysis investigated the differences in diagnosis frequency, RR, and ROM between Western and Asian cytopathology practices. This study demonstrates a difference in Western and Asian thyroid cytology practice, especially regarding the indeterminate categories. Lower RR (51.3% vs. 37.6%) and higher ROM (25.4% vs. 41.9%) suggest that Asian clinicians adopt a more conservative approach, whereas immediate diagnostic surgery is favored in Western practice for indeterminate nodules.

With gene panel tests [65]

Compared with Afirma microarray-based Gene Expression Classifier, Gene Sequencing Classifier (GSC) had a higher benign call rate (BCR) (65.3% vs. 43.8%), a lower RR (26.8% vs. 50.1%), and a higher ROM (60.1% vs. 37.6%). The BCR of Hürthle cell-predominant nodules was significantly elevated (73.7% vs. 21.4%). In addition, the specificity (43.0% vs. 25.1%) and positive predictive value (63.1% vs. 41.6%) of Afirma GSC were significantly improved while it still maintained a high sensitivity (94.3%) and a high negative predictive value (90.0%). With an increased BCR and improved diagnostic performance, GSC could reduce the rate of unnecessary surgical interventions and better tailor the clinical decisions of patients with indeterminate thyroid FNA results.

With molecular tests in Asia [66]

This meta-analysis study included a total of 34 studies with 7,976 indeterminate nodules. The multigene panel testing methods were exclusively used in the United States. Compared with the non-molecular era, molecular testing was associated with a significantly increased ROM (47.9% vs. 32.1%). The ROM of indeterminate nodules in Asian institutes was significantly higher than in Western countries (75.3% vs. 36.6%). Institutes employing single-gene tests achieved a higher ROM (59.8% vs. 37.9%). Molecular testing is a promising method to tailor the clinical management for indeterminate thyroid FNA. The combination of molecular testing and active surveillance enhances the accuracy of case selection for surgery in Asian countries.

Pediatric thyroid carcinoma [67-69]

TBSRTC outputs, including frequency and ROM for most categories, were not statistically different from data in adult patients. However, the RR in the pediatric group was significantly higher in most of the categories compared with published adult data: benign, 23.2% vs. 13.0%; AUS, 62.6% vs. 36.2%; FN, 84.3% vs. 60.5%; and SFM, 93.8% vs. 69.7%. Pediatric patients with benign and indeterminate thyroid nodules had a higher RR than their adult counterparts, but the ROM of these categories in adults and children was not statistically different, suggesting a potential risk of overtreatment in pediatric patients. Determining the best treatment guidelines and additional tools for risk stratification must be a top priority to identify the target patient groups for surgical intervention precisely. Our study further demonstrated that Asian pediatric thyroid nodules had higher ROM than those from adults.

Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in Asian cytology practice [70]

This study examined the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on cytology practice in the Asia-Pacific region involving 167 cytopathology laboratories from 24 countries. The majority reported that restrictive measures that limited the accessibility of health care services had been implemented in their cities and/or countries (80.8%) and their hospitals (83.8%). Approximately one-half of the participants reported the implementation of new biosafety protocols (54.5%) and improving laboratory facilities (47.3%). The majority of the respondents reported a significant reduction (> 10%) in caseload associated with both gynecological (82.0%) and nongynecological specimens (78.4%). Ten out of 14 authors were from the Asian Thyroid Working Group members.

Other meta-analyses of the literature [71-74]

Major fusion oncogenes in PTC [71]

This meta-analysis using 27 studies showed NTRK-, RET-, BRAF-, and ALK-rearranged PTCs had a unique demographic/clinicopathological profile but similar progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival. NTRK1-positive PTCs demonstrated more aggressive clinical behaviors and shorter PFS than NTRK3-positive PTCs, whereas RET rearrangement variants shared comparable clinicopathological backgrounds. This study provides new insights and facilitates our understanding of clinicopathological features and survival outcomes of different fusion oncogenes in PTCs.

The metastatic pattern of thyroid carcinomas [72]

We included 2,787 M1 thyroid cancers for statistical analyses, and the incidence of distant metastasis at presentation was 2.4%. Lung was the most common metastatic site for ATC, poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma, PTC, and oncocytic cell carcinoma, whereas bone is the favorable disseminated site of FTC and MTC. Patients with multi-organ metastases had the worst survival, whereas bone metastases were associated with a favorable outcome. Significant differences exist in distant metastasis patterns of thyroid cancer subtypes and their corresponding survival.

Malignant thyroid teratoma [73]

We incorporated the SEER data with published malignant thyroid teratoma (MTT) cases in the literature to analyze the characteristics and prognostic factors of MTTs. Our results showed that MTT is typically seen in adult females. These neoplasms were associated with an aggressive clinical course with high rates of extrathyroidal extension (80%) and nodal involvement (62%). During follow-up, the development of recurrence and metastases were common (42% and 46%, respectively), and one-third of patients died at the last follow-up.

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma and sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma with eosinophilia [74]

This multicenter study of mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) and MEC with eosinophilia (SMECE) integrated our data with published literature to further investigate these tumors’ clinicopathological characteristics and prognoses. Histopathologically, MECs and SMECEs comprised two main cell types, including epidermoid and mucin-secreting cells, arranged in cords, nests, and tubules. SMECEs were characterized by a densely sclerotic stroma with abundant eosinophils. SMECEs had a superior disease-specific survival rate compared to MECs, suggesting that they are low-grade cancers. This could help clinicians better evaluate patient outcomes and decide appropriate treatment plans.

Future group studies in the Asian Thyroid Working Group

One of the most promising and valuable projects for pathologists is revising thyroid tumor classification, such as refining new tumor entities and establishing a molecular classification of thyroid tumors. The current WHO classification is insufficient for genuine molecular classification, and Western pathologists distinguish RAS-mutated encapsulated follicular pattern thyroid tumors into two tumor groups, FA/tumors of uncertain malignant potential (UMP)/FTC and NIFTP/UMP/FVPTC, according to the absence (NS 0–1) or presence (NS 2–3) of RAS-like dysplastic nuclear features (Fig. 1). This distinction has very little clinical imprecation because both are treated similarly, and the outcomes are almost identical [2,4]. In Asian thyroid practice, the distinction between FA/UMP/FTC and NIFTP/UMP/FVPTC is not strict and often handles them into one tumor lineage, FA/FTC. Thus, NIFTP and FVPTC are rare in Asia [12], while FTC is a vanishing tumor entity and is frequently classified as FVPTC in recent Western practice [75,76]. The lack of uniformity in diagnosing encapsulated follicular pattern tumors with delicate RAS-nuclear features among pathologists creates serious confusion in referring clinicians in some instances and hinders data sharing among institutes. It is a time to combine both RAS-like tumors into one tumor entity, as there are no benefits in the strict sub-classification of RAS-like tumors (FA/UMP/FTC vs. NIFTP/UMP/FVPTC) for treating physicians and patients. The author believes that universally accepted handling of the same RAS oncogene-mutated thyroid tumors is essential to minimize observer variation of encapsulated follicular pattern tumors and establish better communication between Asia and the West, harmonizing them into one world.

SPECIAL ISSUES CONDUCTED BY THE ASIAN THYROID WORKING GROUP MEMBERS

Since 2016, multiple Asian Thyroid Working Group members have curated special issues in various journals. These special issues include:

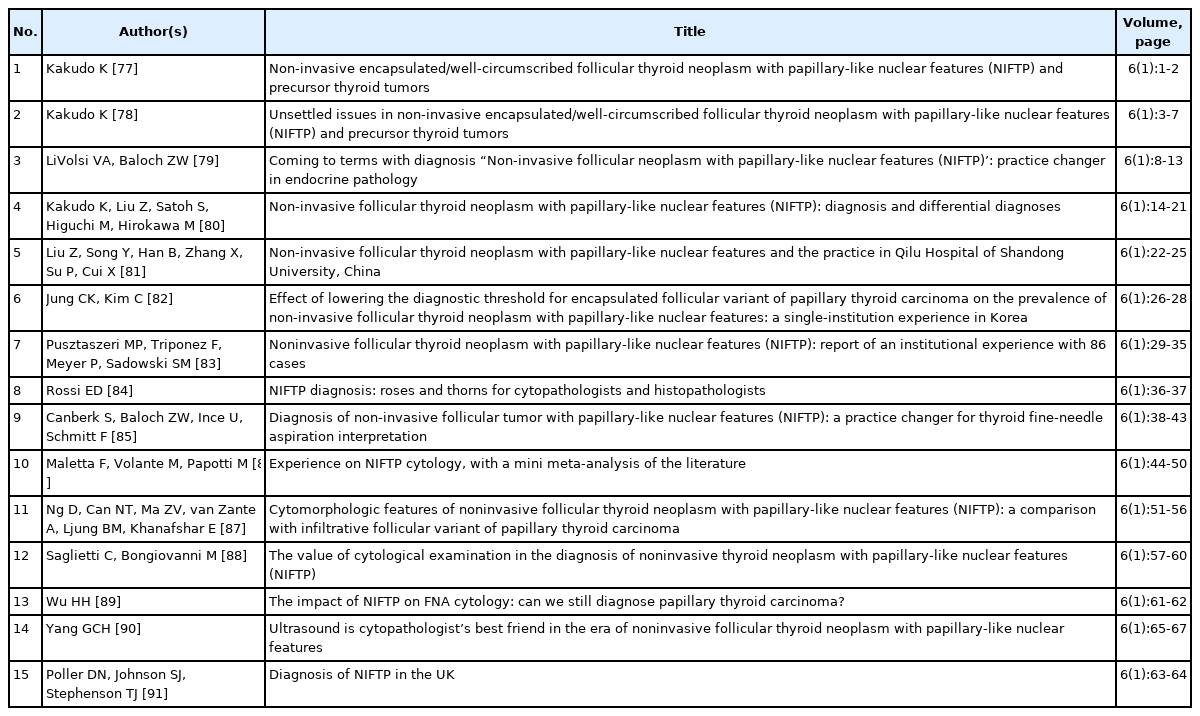

Journal of Basic & Clinical Medicine

In 2016, a pivotal moment in pathology occurred with Nikiforov’s publication of a seminal paper introducing the borderline tumor entity known as NIFTP [23]. Recognizing the importance and potential implications of this new classification, Dr. Kakudo, in the same year, invited a distinguished cohort of 15 international authors, inclusive of four members from the Asian Thyroid Working Group, to present their perspectives and insights on NIFTP in the Journal of Basic & Clinical Medicine (Table 1). It is unfortunate that the journal above subsequently ceased its operations, and its digital presence has vanished. Nevertheless, most of the seminal works, including those discussing NIFTP, are retrievable online, specifically at Dr. Kakudo’s website (http://www.kakudok.jp/english/basic_and_ clinical_medicine/) and the individual ResearchGate profiles of the respective authors.

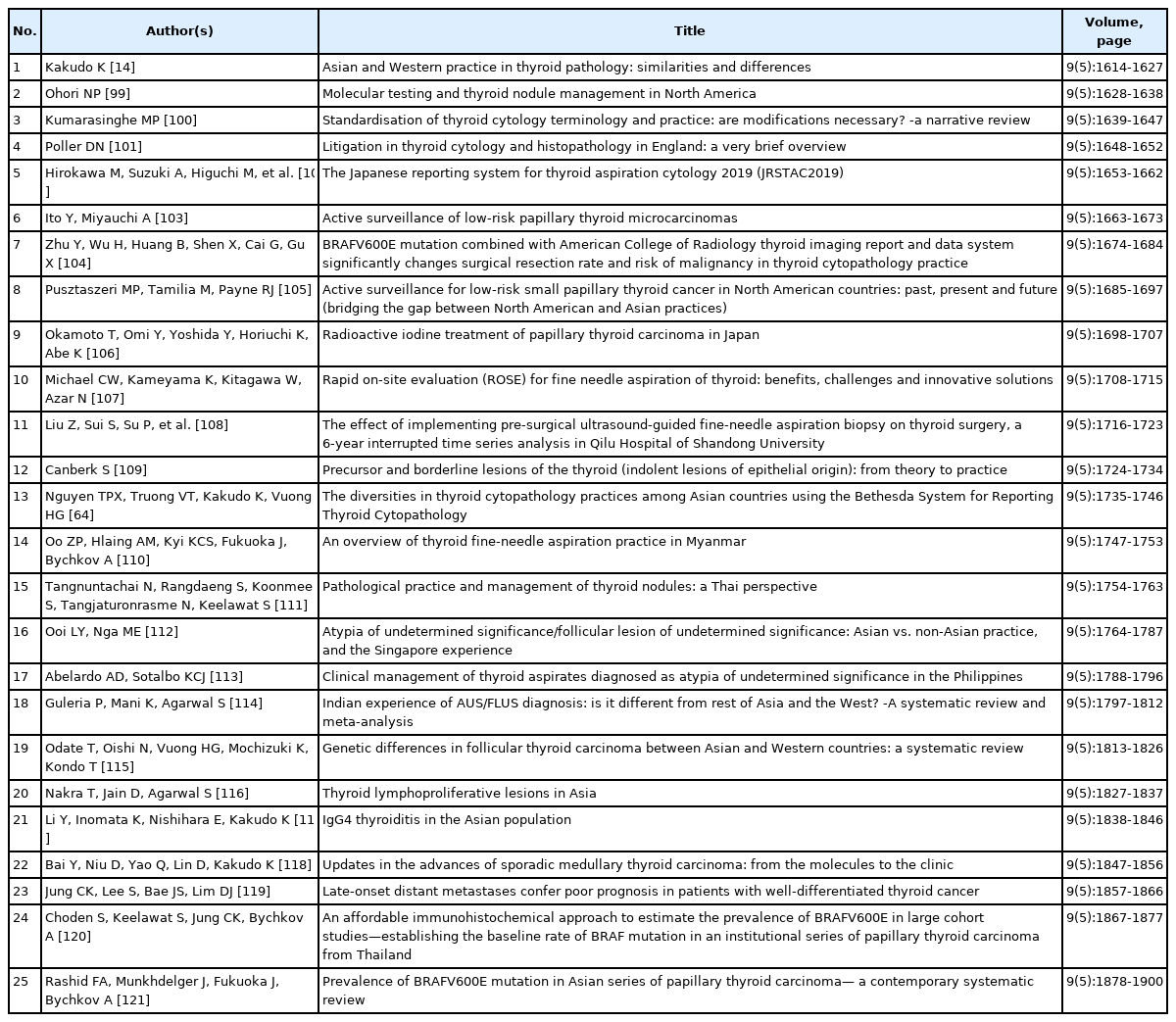

Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine

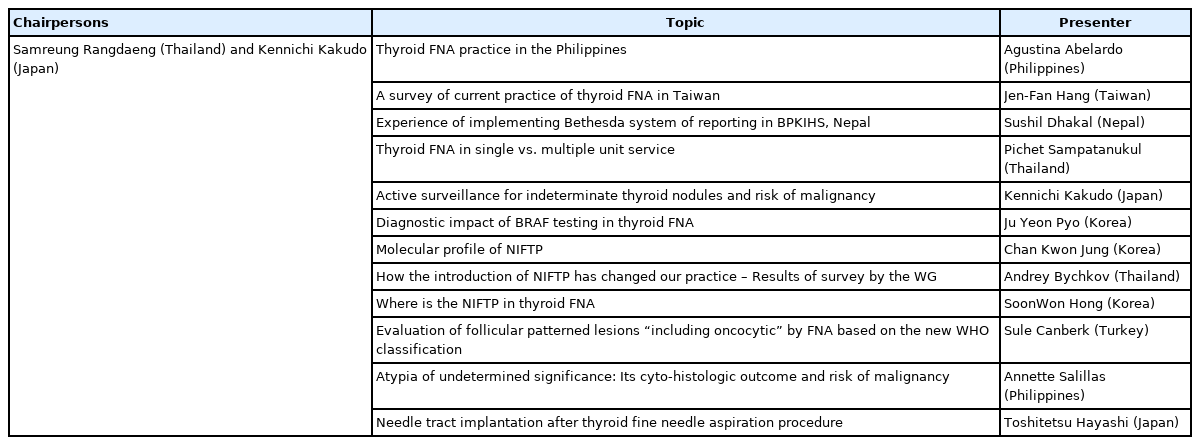

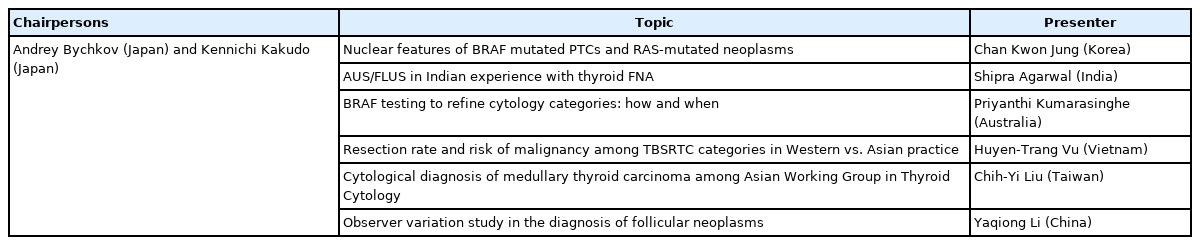

In the AOTA Busan meeting, the Asian Thyroid Working Group commenced its operations in 2017. To begin their collaborative efforts, the Asian Thyroid Working Group summarized and reported the prevailing status of thyroid FNA cytology practices across seven Asian nations. These findings were subsequently published in a special issue of the Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine, sponsored by the Korean Society of Pathologists and the Korean Society for Cytopathology. The articles from this special issue are delineated below in Table 2.

Gland Surgery

“Asian and Western Practice in Thyroid Pathology: Similarities and Differences” was a themed issue published in Gland Surgery (Table 3). It addressed critical differences observed when Western systems for thyroid pathology and cytology were adopted in Asian practice. Dr. Kakudo invited 25 international authors, of which 19 are members of the Asian Thyroid Working Group. These original articles, reviews, and meta-analyses highlight significant differences. Some of these disparities are entirely understandable and expected, while others are deemed scientifically unacceptable and not suitable for patient-centered care.

THE ASIAN THYROID WORKING GROUP COMPANION MEETINGS

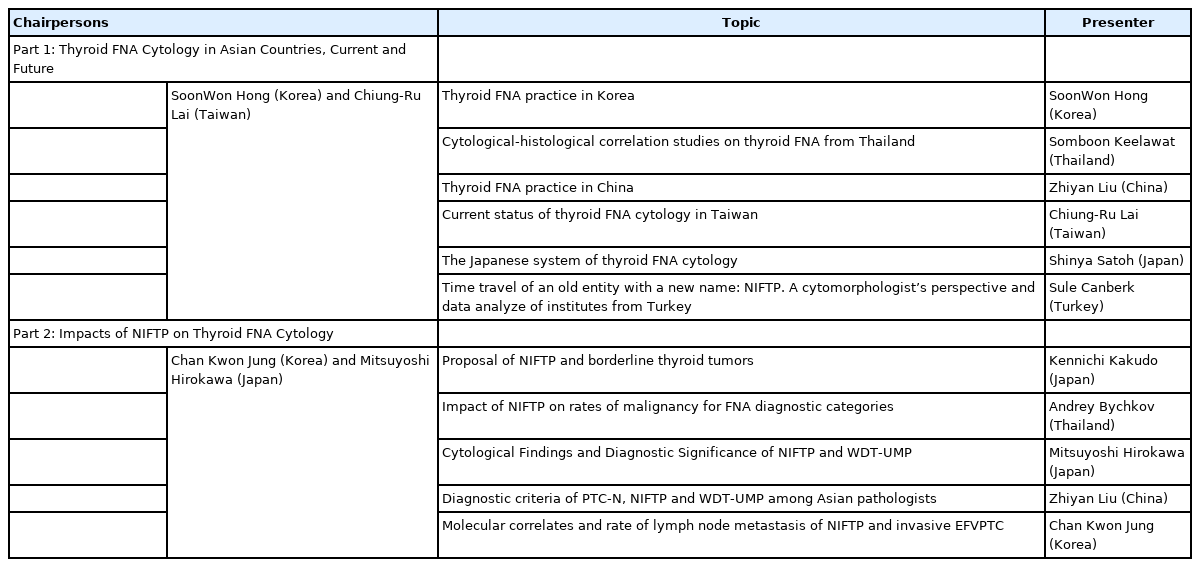

The inaugural Asian Thyroid Working Group Companion Meeting was convened at the 18th AOTA Congress in Busan, Korea, on March 16, 2017. Subsequent Companion Meetings have been held annually, as detailed in Tables 4–8. However, the meetings scheduled for 2020 and 2021 were canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pre-Congress Joint Symposium by Working Group of Asian Thyroid FNA Cytology held on March 16, 2017 in Busan, Korea

The Working Group of Asian thyroid FNA cytology: recent achievements, current activities, and prospective directions was held on January 19, 2018 in Chiang Mai, Thailand, as the second companion meeting by the Asian Thyroid WG

The third Asian Thyroid Working Group Companion Meeting (Asian Practice of Thyroid FNA Cytology) was held on May 8, 2019 at the 20th International Congress of Cytology (ICC Sydney)

On 16th of November 2019, one more (the 4th face to face meeting) companion meeting was held at the 58th Japanese Society of Clinical Cytology (JSCC) Fall Meeting in Okayama, Japan as the Global Asian Forum

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Kennichi Kakudo served as the esteemed president of the Asian Thyroid Working Group from 2017 to 2023, concluding his tenure in July 2023. During this period, the core members who played a pivotal role alongside Dr. Kakudo were Chan Kwon Jung from Korea, Zhiyan Liu from China, Mitsuyoshi Hirokawa from Japan, and Andrey Bychkov, who had affiliations with Russia, Thailand, and Japan. In a significant transition, Chiung-Ru Lai (Taiwan) was nominated as the president in July 2023. This nomination was subsequently ratified during a web meeting held by the core members. As of August 2023, the core team under Dr. Lai’s leadership includes Chan Kwon Jung (Korea), Zhiyan Liu (China), Andrey Bychkov (Japan), Radhika Srinivasan (India), Mitsuyoshi Hirokawa (Japan), Somboon Keelawat (Thailand), with Kennichi Kakudo (Japan) serving as a consultant, and Jen-Fan Hang (Taiwan) fulfilling the role of secretary.

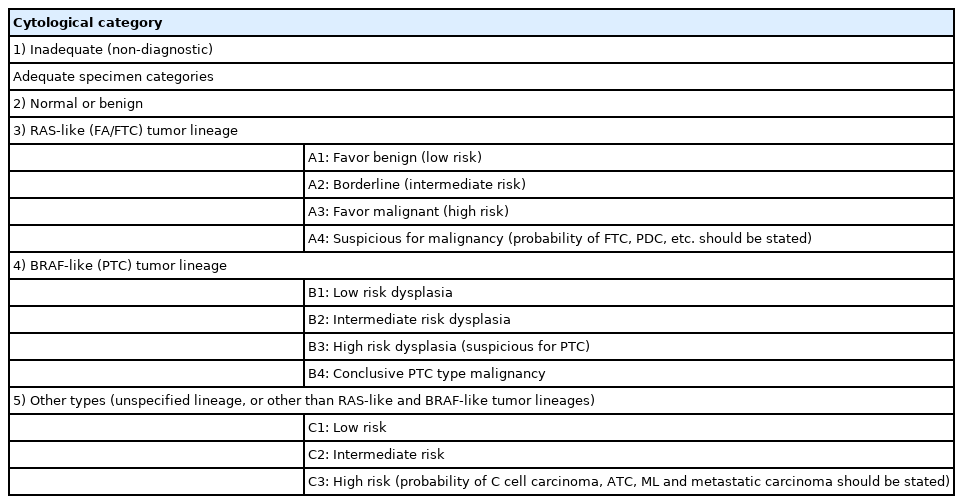

There are numerous group studies that are presently under-way, with their findings expected to be published in the near future. The Asian Thyroid Working Group remains committed to offering a collaborative platform for all its members, which is composed of 58 members from 14 countries in September 2023. A notable contribution to the academic community will be the 3rd edition of “Thyroid FNA Cytology, Differential Diagnosis, and Pitfalls,” slated for release in 2023. This edition will encompass an in-depth discussion of all topics presented in the article as mentioned above [52]. The volume will feature more than 60 chapters penned by esteemed Asian authors. Within these chapters, we present a reporting system tailored to the Asian medical context, given that high-cost gene panel tests are not a commonplace practice (as detailed in Table 9).

The core team, along with the project leader, is enthusiastic about creating more avenues for budding Asian pathologists and cytopathologists to engage with the broader international pathology community. We ardently hope that the activities under the aegis of the Asian Thyroid Working Group will act as a springboard for the younger generation, integrating them with the global community and bolstering their careers in pathology and cytopathology. A list of publications by the Asian Thyroid Working members from 2017 to 2023 is available in Supplementary Table S1.

Supplementary Information

The Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2023.10.04.

A list of publications by the Asian Thyroid Working members from 2017 to 2023

Notes

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

A publication list by Asian WG member is available as a Supplementary Table S1.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: KK. CKJ. Data curation: KK, CKJ, HGV, JFH. Formal analysis: KK. Funding acquisition: KK. Investigation: KK. Methodology: all authors. Project administration: KK. Resources: KK. Supervision: KK. Validation: all authors. Visualization: KK, CKJ, HGV, JFH. Writing—original draft: KK. Writing—review & editing: KK, CKJ, HGV, JFH. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

C.K.J., the editor-in-chief, along with K.K., Z.L., A.B., and C.-R.L., who are contributing editors of the Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine, were not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the members of the Asian Thyroid Working Group for their generous support and collaborations on thyroid disease studies.