Cytological characteristics of Müllerian adenosarcoma of the uterine corpus: a case report and literature review

Article information

Abstract

Müllerian adenosarcoma of the uterus is a rare morphological variant of uterine sarcoma. Müllerian adenosarcoma has been described histologically, though it is rare in the cytological literature. This report describes the cytological findings of a case of adenosarcoma arising from the endometrium. The patient was a Japanese woman in her 40s. Endometrial cytological and histological findings were observed for 5 years, from the appearance of a polypoid lesion until adenosarcoma was suspected, and then hysterectomy was performed. Based on these longitudinal cytological and histological observations, it was possible to identify the cytological characteristics of adenosarcoma: decrease in the glandular-to-stromal ratio; increase in stromal cell density; and progression of stromal cell atypia. This case stresses the importance and usefulness of endometrial cytology in the identification of the sarcomatous component in adenosarcoma.

INTRODUCTION

Müllerian adenosarcoma of the uterus is a rare biphasic malignant tumor composed of a benign glandular component and a malignant, usually low-grade, stromal component. Though the most common site is the uterine corpus, derived from native surface endometrium, it has been reported in the uterine cervix, ovary, vagina, fallopian tube, pelvic peritoneum, and outside the female genital tract, including the intestinal wall, serosa, and liver [1-3]. Adenosarcoma represents <10% of all uterine sarcomas [4], and patients present over a wide age range (median age, 58 years), often with abnormal bleeding or pelvic pain [2]. Histologically, adenosarcoma is characterized by a biphasic tumor composed of a benign epithelial component and a malignant stromal component exhibiting a leaf-like architecture, periglandular cuffing, cell atypia, and variable mitotic activity [1,2,5]. The stromal component is usually low-grade and frequently appears similar to endometrial stromal sarcoma, although high-grade morphology may be present, especially when there is sarcomatous overgrowth, which is defined as pure sarcoma comprising at least 25% of the tumor [2,6].

Because of the disease rarity, the initial histological diagnosis has been correct in about 30% of cases [2]. Moreover, adenosarcoma is mentioned rarely in the cytological literature, and its cytological characteristics have not yet been fully examined; there have been only three case reports of the cytological characteristics of adenosarcoma [7-9]. Therefore, it is difficult to suggest the possibility of adenosarcoma or diagnose adenosarcoma by cytological examination in daily practice. We think that the suggestion or detection of adenosarcoma by cytology, if feasible, is an appropriate approach, and early detection of adenosarcoma by endometrial cytological samples appears to be critical in the management of this neoplasm. In the present case, the cytological and histological findings were observed over time, from the appearance of a polypoid lesion until adenosarcoma was suspected, and then a hysterectomy was performed. Based on the longitudinal cytological and histological observations, it was possible to identify gradually the changes in the cytological findings of the stromal components as the degree of stromal cellular atypia and cellular density increased and then to discuss the cytological characteristics. Therefore, the aim of this publication was to report the cytological characteristics of an adenosarcoma case with a review of prior case reports that discussed the cytological characteristics of uterine adenosarcoma and clarify the usefulness of endometrial cytological examination in its diagnosis.

CASE REPORT

Clinical summary

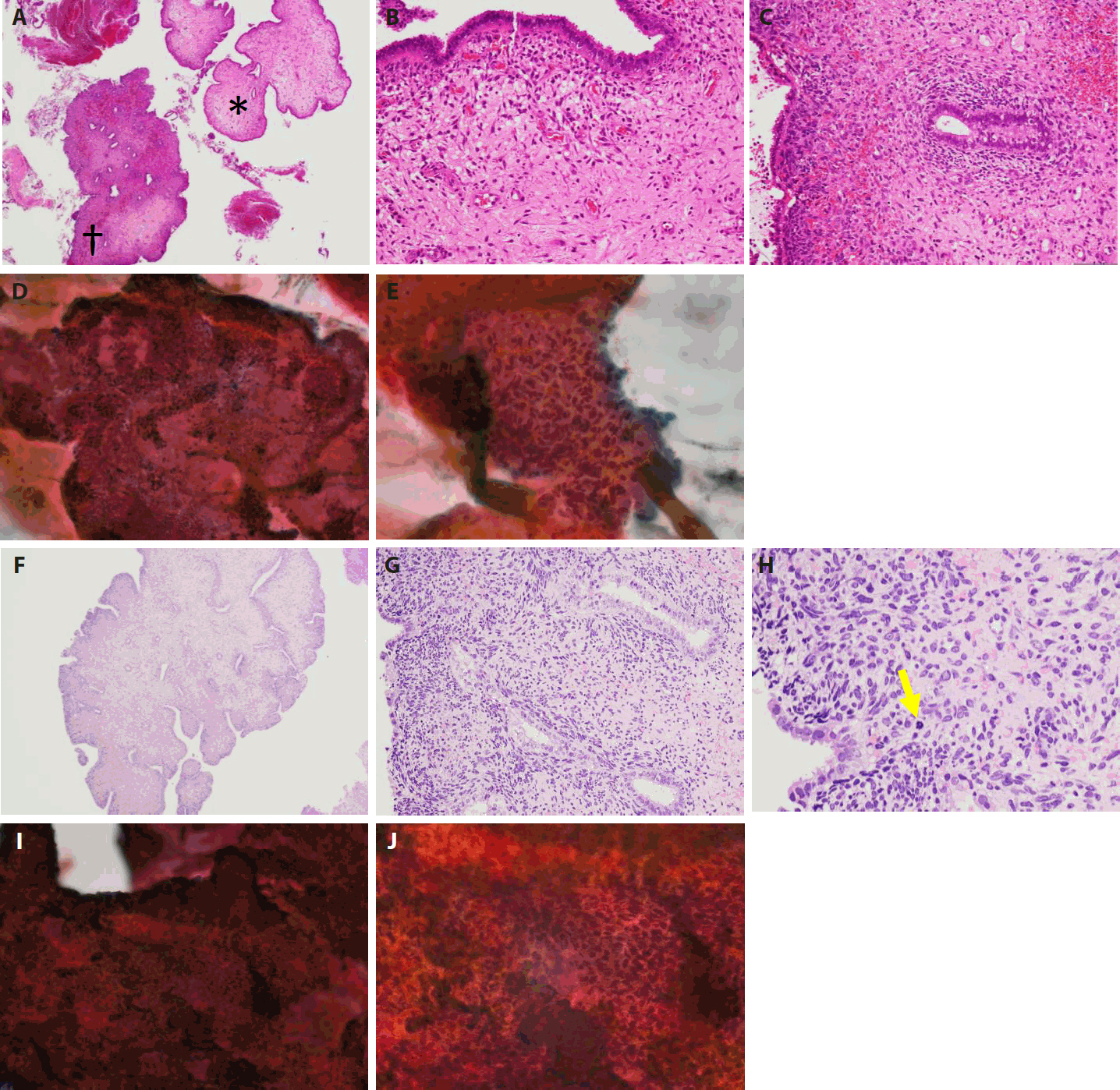

The patient, a Japanese woman in her 40s, had no history of pregnancy or childbirth. She had a history of endometrial polypectomy, and Asherman’s syndrome caused by polypectomy was suspected. During follow-up after the polypectomy, endometrial thickening was identified using ultrasonography to evaluate menstrual irregularities at 3 years after the start of follow-up. Aspiration endometrial cytology and endometrial biopsy were performed, and no neoplastic lesions were found. Owing to persistent endometrial thickening, the patient underwent regular follow-up visits, including aspiration endometrial cytology and endometrial biopsy. Four years after the start of follow-up, a polypoid lesion was observed on the endometrium (Fig. 1A–E). The polypoid lesion showed a tendency to increase in size over time. Aspiration endometrial cytology and endometrial biopsy were performed, and adenosarcoma was suspected 5 years after the start of follow-up (Fig. 1F–J). Hysteroscopy performed just before the operation showed adhesions in the endometrial cavity that hindered observation of the entire cavity, as well as a reddish polypoid lesion (Fig. 2A). Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvic cavity with T2-weighted images obtained just before the operation showed endometrial thickening and a lesion filling the endometrial cavity (Fig. 2B). A simple total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were performed, and adenosarcoma was diagnosed (Fig. 3).

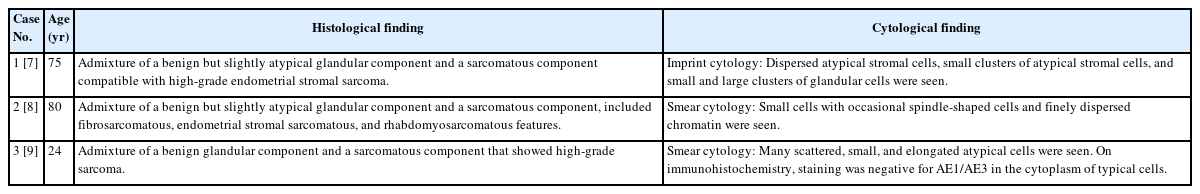

Histological findings of polyp samples collected after appearance of a polypoid lesion and endometrial cytological findings from samples collected at the same time. (A) A hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained section of a polypoid lesion comprising region (*) and region (†). (B) Region (* in A) consists of metaplastic epithelium and stromal tissue with no atypia. (C) Region († in A) shows higher subepithelial stromal condensation than region (* in A). Features resembling periglandular cuffing are seen around these glands. (D) Papanicolaou-stained section of endometrium. The cell cluster includes glands and stroma, and the glandular and stromal densities are in the normal ranges. (E) This is a stromal cell cluster. A sheath of metaplastic epithelium associated with fallopian tube metaplasia is seen in the peripheral area. Though stromal cell density appears slightly increased in places, the stromal cell nuclei are spindle-shaped, and there is no obvious atypia. (F) Histological findings of the polyp biopsy 1 year after the appearance of the polypoid lesion and endometrial cytological findings from samples obtained at the same time. An H&E-stained section of a polypoid lesion. Leaf-like architecture is shown. (G) Subepithelial stromal condensation is high, and periglandular cuffing is obvious. Stromal cell atypia is increased, and nuclear irregularity and nuclear staining are seen. (H) Mitotic activity is observed (yellow arrow). (I) Papanicolaou-stained section of endometrium. This is a cell cluster including epithelial and stromal components, but the proportion of the stromal component is larger than 1 year earlier (D). (J) Stromal cell condensation and nuclear atypia are seen in the stromal component.

Preoperative findings of hysteroscopy and magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvic cavity. (A) On hysteroscopy, adhesions in the endometrial cavity due to suspected Asherman’s syndrome hinder observation of the entire cavity, but a reddish polypoid lesion is seen (yellow arrow). (B) On T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging, endometrial thickening and a lesion filling the endometrial cavity are seen (red arrow).

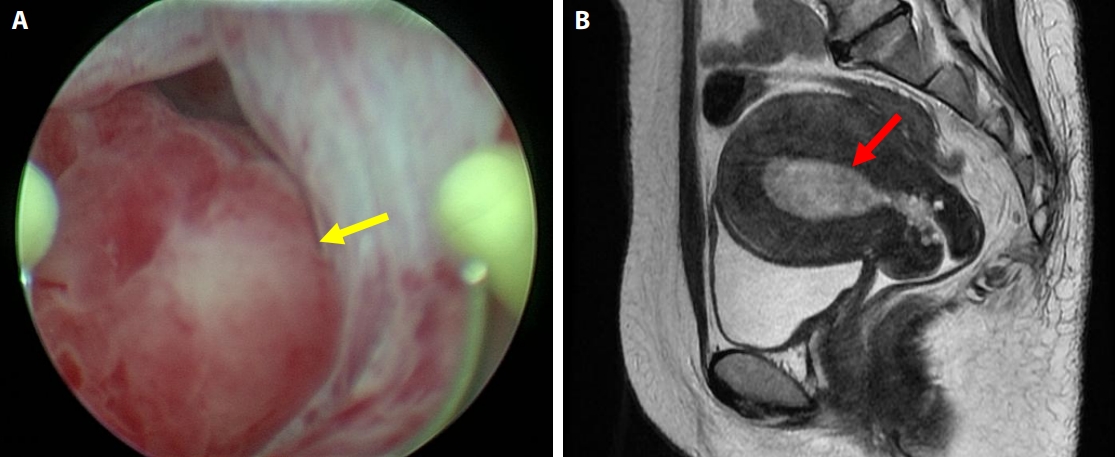

Gross appearance of the tumor. (A) A polypoid mass protruding into the uterine cavity is seen (yellow arrow). (B) At the cross-section of the median incision, an exophytic mass arises from the endometrium. (C) The surface leaf-like architecture is covered with epithelium. Subepithelial stromal condensation is high, and periglandular cuffing is seen. (D) There is metaplastic endometrial glandular epithelium with fallopian tube metaplasia, and nuclear enlargement is seen in subepithelial stromal cells. (E) Mitotic activity is observed (yellow arrows). (F) With immunohistochemical staining for CD10 (E), there is proliferation of anti-CD10 antibody–positive stromal cells, mostly below the epithelium. (G) With immunohistochemical staining, many Ki-67–positive cells are distributed in the stromal tissue just below the epithelium. (H) Imprint cytological findings at the time of the simple hysterectomy. Sheet-like epithelial cell clusters and stromal cell clusters are seen. (I) Atypical cells with irregular, enlarged nuclei adhere to the periphery of the eosinophilic metaplastic epithelial cell cluster. (J) In the stromal cell mass, nuclear staining, nuclear irregularity, and cell condensation are seen. (K) The atypia of the spindle-shaped stromal cells and the increased cell density are more obvious.

Histological findings of polyp biopsy samples and endometrial cytological findings before hysterectomy

First, the histological findings of the polyp biopsy samples collected after the appearance of the polypoid lesion and endometrial cytological findings from samples collected at the same time are considered. Histologically, a polypoid lesion comprises a region (*) of metaplastic epithelium with no atypia and stromal tissue with no atypia and a region (†) of higher subepithelial stromal condensation than region (*) (Fig. 1A–C). In region (†), features resembling periglandular cuffing were observed (Fig. 1C). In the stromal cells, only slight nuclear enlargement was seen, without evident nuclear atypia (Fig. 1C). Cytologically, on a Papanicolaou-stained section of endometrium, the cell cluster included glands and stroma, and the glandular and stromal densities were thought to be in the normal ranges (Fig. 1D). In the stromal cell cluster, a sheath of metaplastic epithelium associated with fallopian tube metaplasia was seen in the peripheral area (Fig. 1E). Though stromal cell density appeared slightly increased in places, mostly directly under the epithelium, the stromal cell nuclei were spindle-shaped, and there was no obvious atypia (Fig. 1E).

The histological findings of the polyp biopsy 1 year after the appearance of the polypoid lesion were compared to cytological findings from endometrial samples collected at the same time. Histologically, a polypoid lesion showed a leaf-like architecture (Fig. 1F). Subepithelial stromal condensation was high, and periglandular cuffing was obvious (Fig. 1G). Stromal cell atypia was increased, and nuclear irregularity and nuclear staining were seen (Fig. 1G). Mitotic activity was easily observed (Fig. 1H), and the mitotic count was five mitoses per 10 high-power fields in a hot spot. Cytologically, a cell cluster included epithelial and stromal components, but the proportion of the stromal component was higher than the one shown in Fig. 1D (Fig. 1I). Stromal cell condensation and atypia were seen in the stromal component (Fig. 1J). Based on these histological and cytological findings, adenosarcoma was suggested.

Gross, histological, and imprint cytological findings of the polypoid lesion in hysterectomy specimens

Grossly, the tumor was a 5.5 × 4.0 × 3.5 cm exophytic mass arising from the endometrium. It exhibited exophytic growth and filled the endometrial cavity, and there was no obvious necrosis (Fig. 3A, B).

Histologically, the tumor showed an irregular leaf-like architecture, and cystic dilation of glandular ducts was seen (Fig. 3C). The surface leaf-like architecture was covered with epithelium. Subepithelial stromal condensation was high, and periglandular cuffing was seen (Fig. 3D). There was metaplastic endometrial glandular epithelium with fallopian tube metaplasia, and nuclear enlargement was seen in subepithelial stromal cells (Fig. 3D, E). Mitotic activity was easily observed (Fig. 3E), and the mitotic count was 10 mitoses per 10 high-power fields in a hot spot. Immunohistochemical staining for CD10 showed a proliferation of anti-CD10 antibody–positive stromal cells, mostly immediately below the epithelium (Fig. 3F). With immunohistochemical staining for Ki-67, many Ki-67–positive cells were distributed in the stromal tissue just below the epithelium (Fig. 3G). The malignant stromal component was equivalent to low-grade malignancy and was homologous. No high-grade and no heterologous stromal components were seen.

Cytologically, endometrial imprint cytology at the time of the hysterectomy showed sheet-like epithelial cell clusters and stromal cell clusters (Fig. 3H). Atypical stromal cells with irregular, enlarged nuclei adhered to the periphery of the eosinophilic metaplastic epithelial cell cluster (Fig. 3I). The stromal cell mass presented nuclear staining, nuclear irregularity, and cell condensation (Fig. 3J). The atypia of the spindle-shaped stromal cells and the increased cell density were obvious. The nuclei were usually oval with nuclear cleavage and coarse chromatin. One or two nucleoli were also noted (Fig. 3K).

Literature review

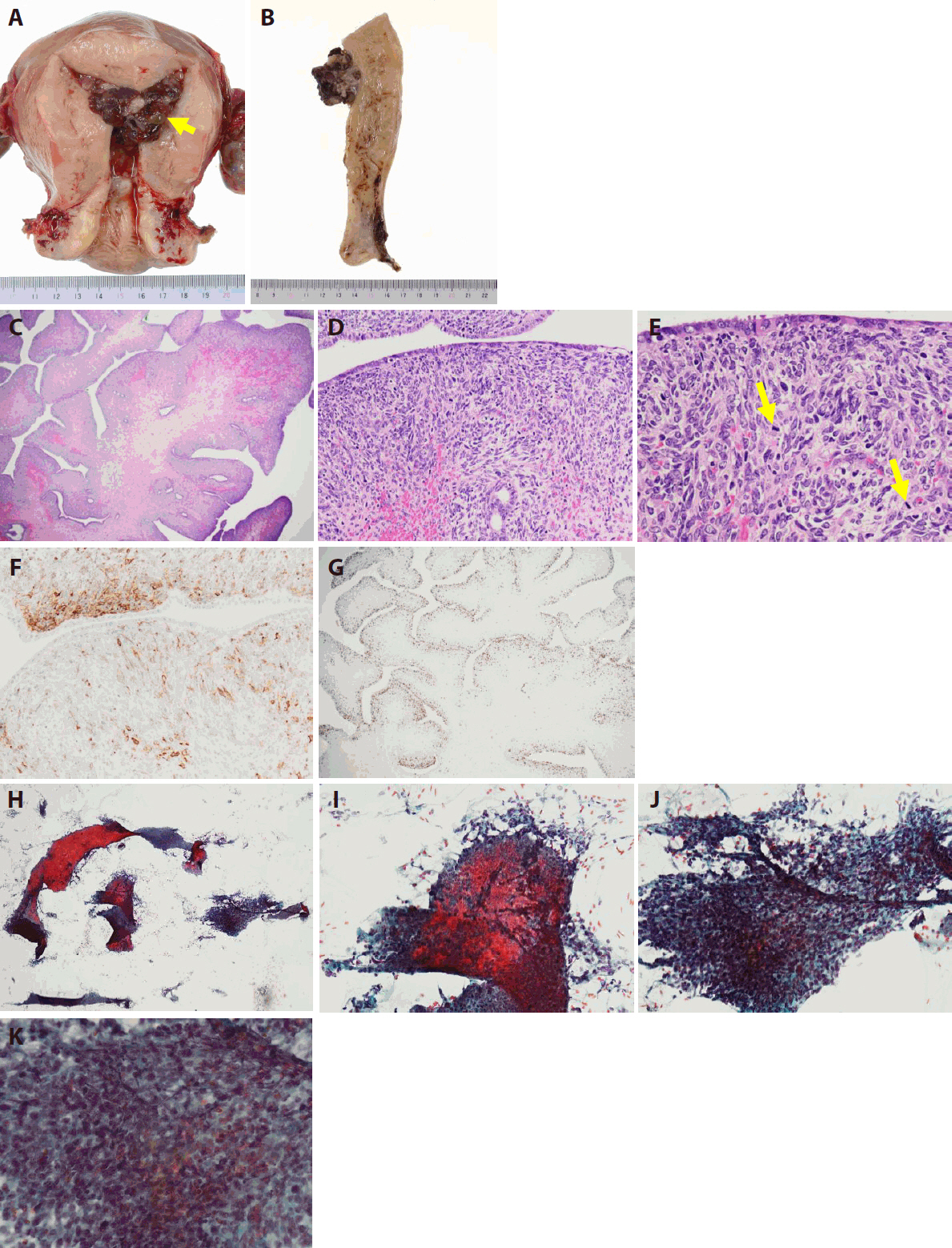

Three published reports describing the cytological findings of uterine adenosarcoma were identified [7-9]. Two were derived from the endometrium, and one was derived from the uterine cervix. The histological and cytological features of the three cases are summarized in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Müllerian adenosarcoma was first described in 1974 [9]. Some subsequent reports have expanded the clinicopathological spectrum of these neoplasms, and adenosarcoma is now recognized as a rare malignant tumor, generally of low malignant potential and most commonly arising in the uterine corpus [1-3].

Histologically, adenosarcoma is characterized by a phyllodes-like architecture. The architecture reflects the proliferation of malignant stroma, which is usually low-grade, although high-grade morphology may be present, associated with sarcomatous overgrowth. The malignant stroma is usually homologous and shows spindle-shaped morphology. In most cases, it is characterized by increased cellularity surrounding the epithelial component, which is called periglandular cuffing; variable but often cytological atypia; and a low mitotic rate [2,10]. In fewer cases, heterologous differentiation and sarcomatous overgrowth are seen.

Although the histological characteristics of adenosarcoma have been described, the cytological characteristics of adenosarcoma are not fully understood. Only three previous reports have described the cytological findings of adenosarcoma originating in the uterus [7-9]. In all three of the reports, it was stated that, when dispersed atypical stromal cells are observed, adenosarcoma needs to be included in the differential diagnosis (Table 1). The reason for the small number of reports is thought to be related to the rarity of adenosarcoma itself. In addition, there is a tendency to focus on differentiation of the glandular component of endometrial hyperplasia, atypical endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrioid carcinoma, and the findings of the stromal component are overlooked. Moreover, endometrial cytology has not been widely used because of accuracy issues, which are most likely due to the common presence of excess blood and overlapping cells. However, the recent use of liquid-based cytology has provided an opportunity to evaluate the role of endometrial cytology [11,12]. Accordingly, the usefulness of endometrial cytology in the diagnosis of intrauterine lesions, such as endometrial carcinoma, carcinosarcoma, and various types of benign lesions, has been reported [11,13,14]. The usefulness of endometrial cytology in daily practice have been demonstrated in one institution for diagnosis of intrauterine lesions, together with histological diagnosis.

In the present case, considering the chronological cytological findings, not only did the proportion of the stromal component increase gradually compared with the glandular component, but stromal cell condensation was observed to increase over time, with increasing cellular atypia. Dispersed atypical stromal cells, which were seen in the previous case reports [7-9], were not detected in the preoperative endometrial aspiration cytology or imprint cytology collected at the hysterectomy. In one of the previous case reports [7], it was stated that, although preoperative endometrial aspiration cytology failed to prove the presence of adenosarcoma, probably because a large proportion of the tumor surface was covered with benign epithelial elements, imprint cytology at the time of the hysterectomy detected the dispersed atypical stromal cells and small clusters of atypical stromal cells, adequately depicting the pathological features. Unlike previous reports, in the present case, preoperative aspiration cytology showed sufficient cell clusters with an atypical stromal component. In previously reported cytological cases of uterine adenosarcoma, each involving high-grade stromal components, the atypical stromal cells were observed as dispersed individual cells, likely reflecting reduced cell-cell adhesion in high-grade sarcomatous stroma. In contrast, the present case featured low-grade stromal pathology with atypia, where the stromal component appeared as cellular aggregates or clusters surrounded by epithelial elements, particularly associated with fallopian tube metaplasia. We hypothesize that, in low-grade stromal lesions, intercellular adhesion is stronger, resulting in the appearance of atypical stromal cell clusters rather than dispersed cells on cytology. Although no study directly addresses adhesion differences between high- and low-grade stromal components in adenosarcoma cytology, this hypothesis is consistent with general observations in soft tissue tumor biology that high-grade tumors often lose adhesion and become more dissociative, whereas low-grade tumors maintain cohesive growth [15]. Supporting this concept, studies of malignant phyllodes tumors of the breast, which are histologically similar to adenosarcoma, have reported that high-grade tumors tend to show weaker intercellular adhesion than low-grade ones [16,17].

Given this, in cases of low-grade adenosarcoma, careful cytological evaluation should focus not on the presence of scattered atypical stromal cells, which may be absent, but rather on clusters of stromal cells with atypia and a decreased glandular-to-stromal ratio. It is assumed that cytological recognition of atypical stromal components may be easier in cases of high-grade sarcoma than in the present case of low-grade sarcoma, because markedly atypical nuclei are more readily identifiable. Therefore, we believe that careful observation of the proportion of stromal component, stromal cell density, and atypia of stromal cells in cell clusters can provide information that may aid in the diagnosis of adenosarcoma.

Considering the above, focus should be directed to both glandular and stromal components in endometrial cytology. The key points that suggest the possibility of adenosarcoma or definitive diagnosis of adenosarcoma on cytological examination are (1) decrease in the glandular-to-stromal ratio; (2) increase in stromal cell density; and (3) progression of stromal cell atypia. These points are important to not overlook adenosarcoma on cytological examination. Clinically, it is important to follow persistent endometrial thickening and recurrent polyp lesions with cytological and histological examinations over time.

Notes

Ethics Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the individual participant included in this study. This case report was approved by the ethics committee of the Tokyo Saiseikai Central Hospital (IRB No. CR-172).

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: JK, SH. Data curation: JK, CM, YS, HT, SH. Writing—original draft: JK. Writing—review & editing: JK. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding to declare.