Diagnostic challenge in Burkitt lymphoma of the mandible initially misdiagnosed as osteomyelitis: a case report

Article information

Abstract

Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is a highly aggressive B-cell neoplasm that rarely involves the mandible in elderly without apparent immunodeficiency. We report a case of a 72-year-old male who presented with persistent mandibular pain following extraction of tooth #46. Initial imaging findings were consistent with incipient osteomyelitis, and the patient was treated with antibiotics. Despite treatment, pain persisted, and follow-up imaging revealed swelling and diffusion restriction in the lateral pterygoid muscle without evidence of a distinct mass. Biopsy revealed BL confirmed by immunohistochemistry: CD10+, BCL6+, c-MYC+, Ki-67 >95%, and negative for BCL2, MUM-1, and Epstein-Barr virus. Although c-MYC immunopositivity was demonstrated, fluorescence in situ hybridization for rearrangement could not be performed due to limited tissue, representing a diagnostic limitation. Notably, the patient had no trismus despite deep muscle involvement, but complained of facial paresthesia and showed remote swelling in the scapular area during hospitalization. Systemic staging with imaging, cerebrospinal fluid cytology, and imaging revealed disseminated nodal and extranodal involvement including the central nervous system, corresponding to stage IV disease by Lugano classification. This case highlights the diagnostic challenge of distinguishing lymphoma from osteomyelitis and underscores the importance of considering malignancy in cases of refractory mandibular inflammation with atypical features.

INTRODUCTION

Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is an aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by a high proliferative index and frequent MYC gene rearrangements [1-5]. While the disease most commonly involves abdominal organs such as the ileocecal region and mesentery, extramedullary involvement of the head and neck region may occur, particularly in immunocompromised individuals or in endemic forms [1,5,6]. Although up to 10%–15% of BL cases show head and neck involvement [7], sporadic BL involving the mandible in elderly patients remains exceedingly rare [8] and poses a significant diagnostic challenge. Mandibular BL is often radiographically and clinically indistinguishable from chronic osteomyelitis or odontogenic infections, particularly in the absence of overt mass formation or systemic symptoms, leading to potential diagnostic delay.

Here, we report a rare case of sporadic, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–negative BL involving the right mandible in a 72-year-old patient who presented with persistent mandibular pain and was initially diagnosed and treated as osteomyelitis. The disease progressed despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy, and the correct diagnosis was ultimately confirmed by biopsy and immunohistochemical analysis. This case highlights the need for heightened suspicion of malignancy when clinical and radiographic findings are atypical or refractory to conventional treatment.

CASE REPORT

A 72-year-old man presented with persistent pain in the right mandibular molar region. He initially underwent root canal treatment of mandibular right first molar (#46, FDI system) at a local dental clinic; however, symptoms persisted, ultimately necessitating extraction of the involved tooth. Despite this, his discomfort continued, prompting referral to our institution for further evaluation. The patient was otherwise in good general health, with no history of immunodeficiency, and had only well-controlled hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

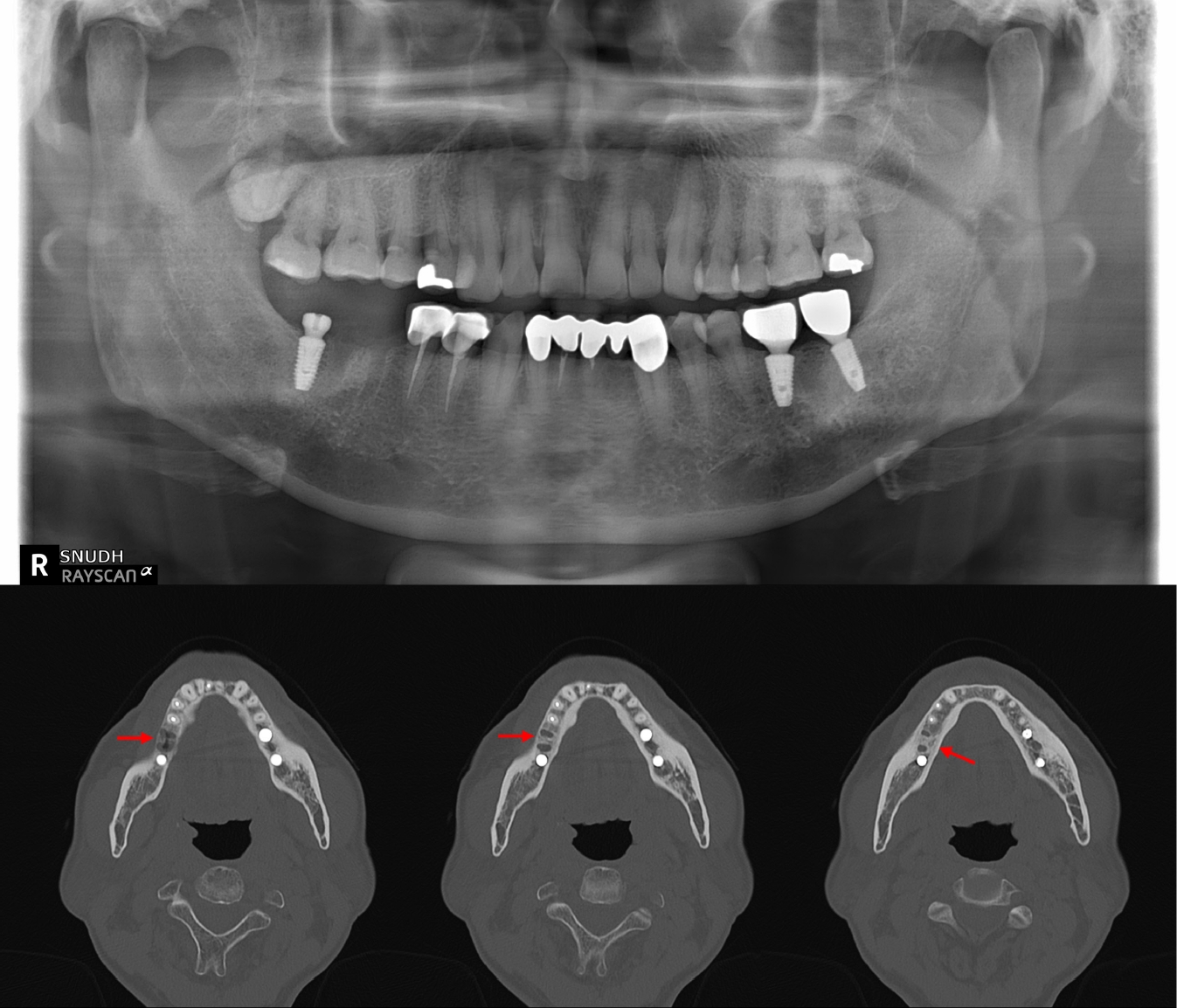

Initial panoramic view and non-contrast computed tomography (CT) of the mandible showed thickening of the lamina dura and irregular residual alveolar crest at the #46 extraction site (Fig. 1). Based on the clinical presentation and radiologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with incipient osteomyelitis of the right mandibular body, and oral antibiotic therapy was initiated.

Initial panoramic and computed tomography (CT) imaging findings of the mandible. Panoramic radiograph shows the extraction socket at the #46 site. Non-contrast axial CT image reveals thickening of the lamina dura and irregular residual alveolar crest at the right mandibular body (arrows), consistent with early-stage osteomyelitis.

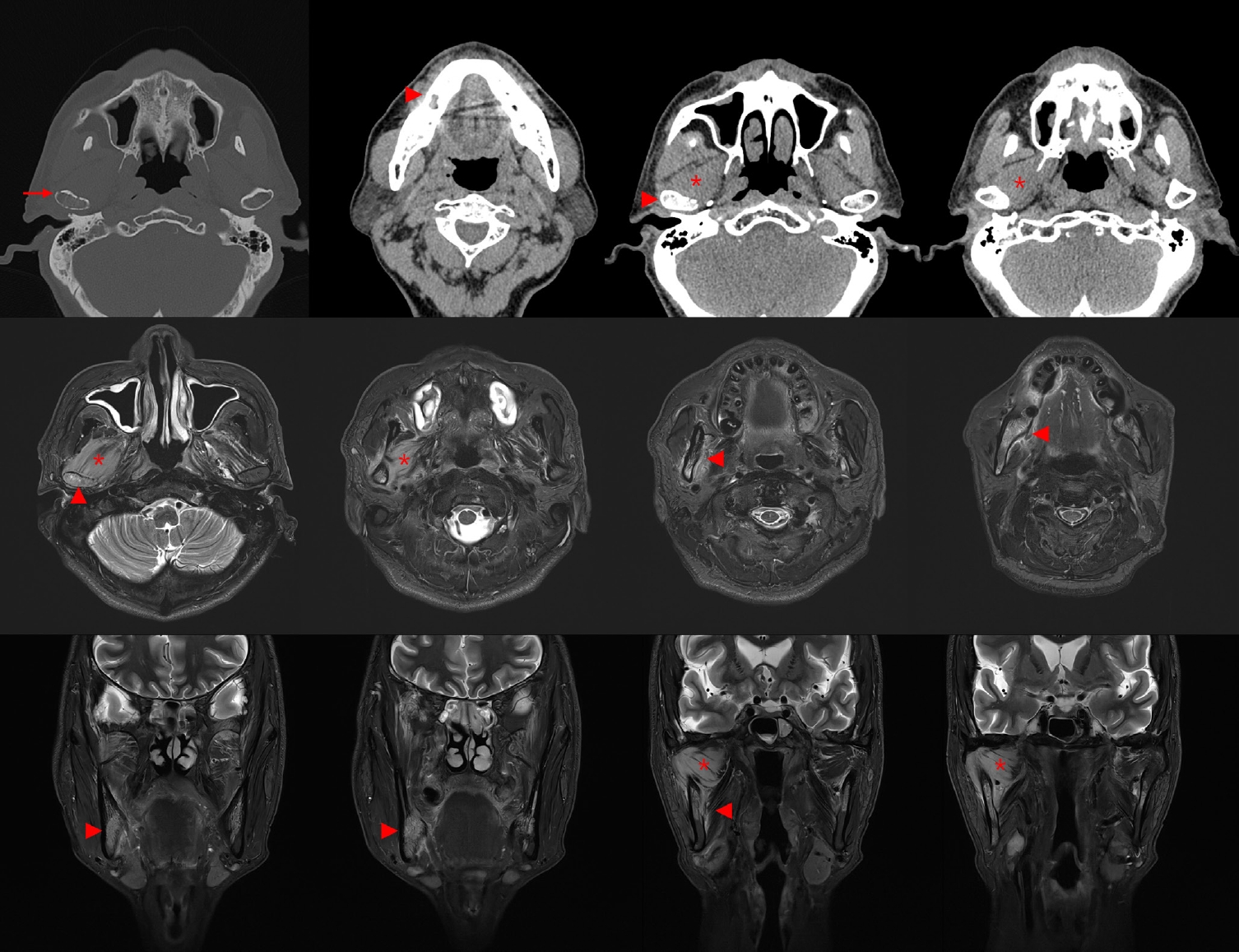

One month later, follow-up CT revealed cortical erosion of the right mandibular condyle, increased bone marrow attenuation, and swelling of the right lateral pterygoid muscle. Magnetic resonance imaging further showed diffuse hyperintensity of the mandibular body marrow and perimandibular soft tissues on T2-weighted images, with extension to the mandibular foramen and condyle. Marked swelling and diffusion restriction of the lateral pterygoid muscle were also noted, suggestive of progressive inflammation (Fig. 2).

Follow-up computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) imaging showing progressive bony and soft tissue changes. Axial CT image obtained 1 month after initial presentation shows cortical erosion of the right mandibular condyle and increased bone marrow attenuation in the right mandibular ramus. T2-weighted MRI reveals diffuse hyperintensity in the mandibular marrow and surrounding soft tissues and restricted diffusion in the right lateral pterygoid muscle. No distinct mass lesion is identified, despite these progressive changes. Arrows indicate cortical erosion, arrowheads indicate increased attenuation of bone marrow and periosteum, and asterisks indicate swelling of lateral pterygoid muscle.

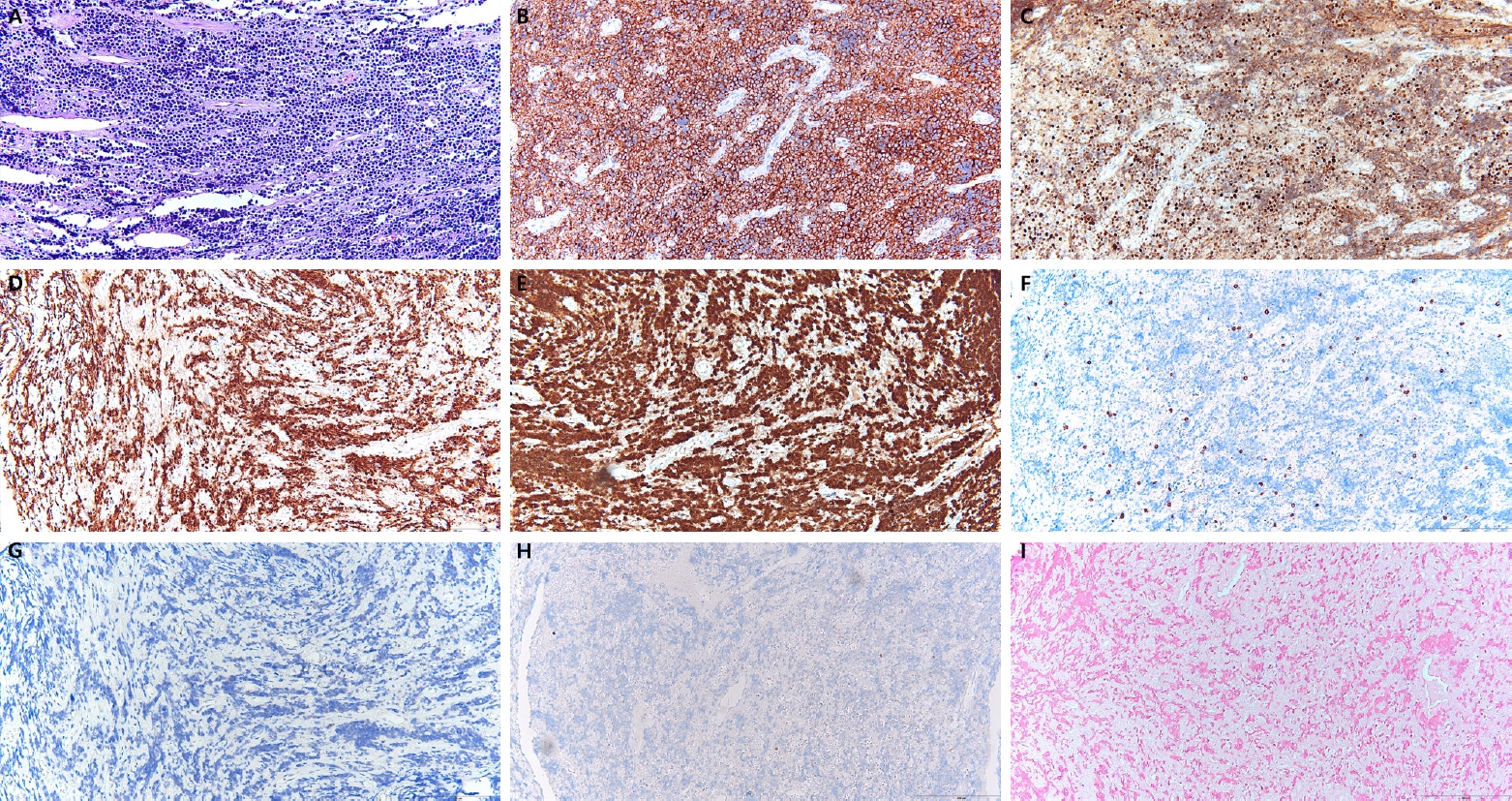

Histopathologic examination of the mandibular biopsy demonstrated diffuse infiltration of medium-sized atypical lymphoid cells with round nuclei, fine chromatin, and frequent mitotic figures. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells were diffusely positive for CD10, BCL6, and c-MYC (homogeneously >90%), with nearly 100% Ki-67 proliferation index. They were negative for BCL2, MUM-1, and EBV. Focal cytoplasmic positivity for CD3 was observed but, in the absence of other T-cell markers, was regarded as nonspecific (Fig. 3).

Histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings of the mandibular lesion. Hematoxylin and eosin staining showing diffuse infiltration of medium-sized atypical lymphoid cells with round nuclei, fine chromatin, and numerous mitotic figures, consistent with a high-grade lymphoma (A). Immunohistochemistry for CD10 demonstrating diffuse membranous positivity (B). BCL6 showing diffuse nuclear positivity (C). c-MYC exhibiting strong nuclear expression in more than 90% of tumor cells (D). Ki-67 proliferation index approaching 100% (E). Tumor cells negative for BCL2, MUM-1, and Epstein-Barr virus (F–H). Focal cytoplasmic staining for CD3 was observed (I).

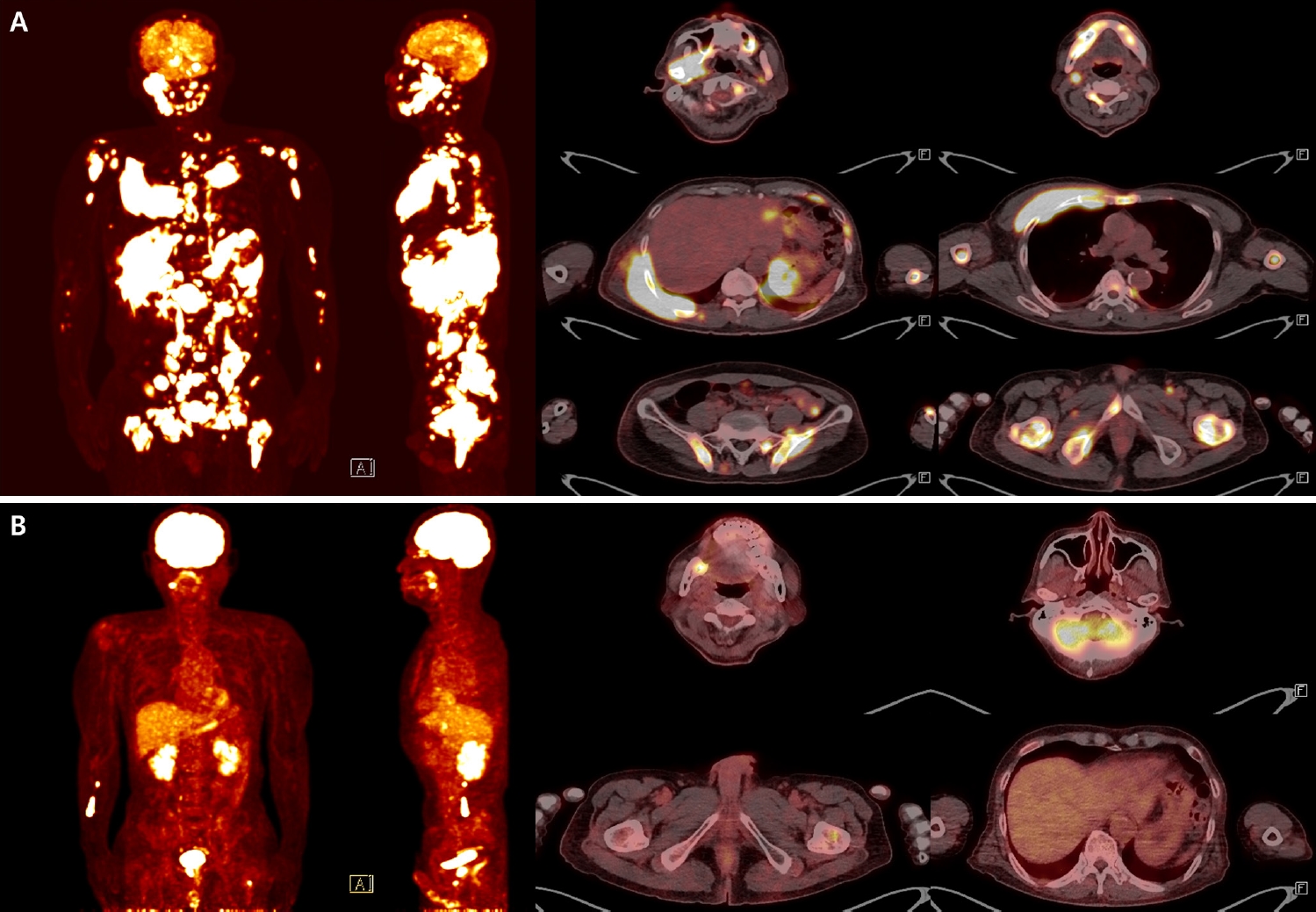

Subsequent systemic work-up revealed widespread disease. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) demonstrated probable lymphoma involvement of lymph nodes above and below the diaphragm, bones, nasopharynx, tonsil, stomach, subcutaneous tissue and muscles, and lung (Fig. 4A). Cerebrospinal fluid cytospin was positive for malignant lymphoid cells, confirming central nervous system dissemination. In addition, orbit and head CT revealed a suspicious expansile soft tissue lesion in the right ethmoid sinus, together with mild bilateral maxillary sinus mucosal thickening.

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography–computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) images at diagnosis and after chemotherapy. Baseline FDG-PET/CT at diagnosis demonstrates disseminated hypermetabolic lesions involving multiple nodal stations (bilateral neck, axilla, mediastinum, abdomen, and pelvis) and extensive extranodal sites, including the skull, mandible, spine, long bones, clavicle, sternum, ribs, scapula, pelvis, lung, stomach, gallbladder, pancreas, nasopharynx, tonsil, and widespread subcutaneous and muscular tissues, consistent with advanced-stage Burkitt lymphoma (A). Follow-up FDG-PET/CT after the fourth cycle of chemotherapy shows a markedly improved state. Only focal residual uptake persists in the right mandible and left proximal femur (B).

Collectively, these findings were diagnostic of BL. Systemic staging with FDG-PET, cerebrospinal fluid cytology, and CT imaging revealed disseminated nodal and extranodal involvement including the central nervous system, corresponding to stage IV disease by Lugano classification. Given the widespread disease and central nervous system involvement, the therapeutic approach was palliative rather than curative. The patient presented with B symptoms, including weight loss and febrile sense, and was initiated on systemic chemotherapy with R-EPOCH (rituximab, etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin). Intrathecal methotrexate (IT-MTX) was administered for central nervous system prophylaxis and treatment, and he is currently undergoing the fourth cycle of R-EPOCH with IT-MTX. Thus far, the patient has tolerated therapy well without treatment-related complications, and follow-up imaging demonstrated marked improvement of the lesions (Fig. 4B).

DISCUSSION

BL is an aggressive B-cell neoplasm with distinct epidemiologic variants. Endemic BL, strongly associated with EBV, typically presents in the jaw and facial bones of children, whereas sporadic BL more commonly involves intra-abdominal organs in younger patients [1-5]. Jaw involvement in elderly individuals without apparent immunodeficiency is rare, and very few cases of sporadic, EBV-negative BL of the mandible have been reported in this age group [8-12].

In the present case, the initial clinical and radiologic findings closely resembled osteomyelitis. Osteomyelitis of the jaw is typically characterized by localized pain, sclerosis of trabecular bone, periosteal reaction, sequestrum formation, and sinus tract development [13,14]. In contrast, malignant bone lesions—including primary bone lymphomas—more often demonstrate rapidly progressive, ill-defined osteolysis, cortical destruction, and associated soft tissue masses [15]. Our patient initially showed lamina dura thickening and subtle marrow signal change, mimicking early infection, but atypical features emerged over time. These included persistent inflammatory marker elevation despite antibiotics, perineural symptoms such as facial paresthesia, and deep muscle involvement without abscess or trismus, all of which raised suspicion for malignancy.

When lymphoma involves the maxillofacial skeleton, imaging often reveals diffuse marrow replacement, cortical thinning or destruction, and soft tissue extension without abscess formation [16,17]. Reports have shown that such presentations are frequently mistaken for odontogenic infection or osteomyelitis, leading to delayed diagnosis [11,18,19]. This case underscores the diagnostic dilemma posed by primary bone lymphomas mimicking inflammatory disease and emphasizes the importance of early biopsy when conventional treatment fails.

In the present case, the differential diagnosis included diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), high-grade B-cell lymphoma (HGBCL), and BL. DLBCL was considered less likely because the tumor cells in our case were morphologically monotonous and of medium size, lacking the pleomorphism typically seen in DLBCL. Moreover, the proliferation index approached 100%, which is unusually high for DLBCL. HGBCL, particularly the double-hit or triple-hit subtype, may resemble BL; however, these entities generally harbor MYC rearrangements in combination with BCL2 and/or BCL6 translocations. In contrast, our case showed the classic immunophenotypic profile of BL, with diffuse CD10, and BCL6 positivity, nearly 100% Ki-67, and negativity for BCL2 and MUM-1. Although molecular confirmation of MYC rearrangement could not be performed due to limited tissue, the combination of morphology, immunophenotype, and clinical presentation was most consistent with BL rather than DLBCL or HGBCL [6,20-22].

This study has limitations. The biopsy specimen was obtained by curettage at the dental hospital, and the slides were subsequently referred to the medical hospital for diagnostic consultation. Because only limited tissue was available and evaluation relied on a restricted number of slides, additional molecular studies such as fluorescence in situ hybridization for MYC rearrangement could not be performed. Furthermore, as the patient has already initiated systemic chemotherapy, retrospective molecular testing is not feasible. Although the morphology and immunophenotypic profile were highly characteristic of BL, the absence of molecular confirmation represents a diagnostic limitation.

In conclusion, this case illustrates the diagnostic challenge of distinguishing BL from osteomyelitis in the mandible of an elderly patient. Subtle radiographic changes, lack of a distinct mass, and initial resemblance to infection delayed recognition of the malignancy. However, persistent symptoms, rising inflammatory markers despite antibiotics, and atypical features such as perineural involvement should prompt early biopsy to exclude lymphoma. Clinicians should maintain a broad differential diagnosis for refractory mandibular inflammatory lesions, as timely recognition of BL is essential for initiating appropriate therapy in this aggressive disease.

Notes

Ethics Statement

Formal written informed consent was not required with a waiver by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Dental Hospital (IRB No. ERI25038).

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: JYC. Investigation: JD. Writing—original draft: JD. Writing—review & editing: JD, JYC. Supervision: JYC. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding to declare.