Proposal for Creating a Guideline for Cancer Registration of Microinvasive Tumors of the Breast and Ovary (II)

Article information

Abstract

Background

Cancer registration in Korea has a longer than 30-years of history, during which time cancer registration has improved and become well-organized. Cancer registries are fundamental for cancer control and multi-center collaborative research. However, there have been discrepancies in assigning behavior codes. Thus, we intend to propose appropriate behavior codes for the International Classification of Disease Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3) for microinvasive tumors of the ovary and breast not only to improve the quality of the cancer registry but also to prevent conflicts.

Methods

As in series I, two pathology study groups and the Cancer Registration Committee of the Korean Society of Pathologists (KSP) participated. To prepare a questionnaire on provisional behavior code, the relevant subjects were discussed in the workshop, and consensus was obtained by convergence of opinion from members of KSP.

Results

Microinvasive tumor of the breast should be designated as a microinvasive carcinoma which was proposed as malignant tumor (/3). Serous borderline tumor with microinvasion of the ovary was proposed as borderline tumor (/1), and mucinous borderline tumor with microinvasion of the ovary as either borderline (/1) or carcinoma (/3) according to the tumor cell nature.

Conclusions

Some issues should be elucidated with the accumulation of more experience and knowledge. Here, however, we present our second proposal.

Development of an efficient cancer control program is essential, considering that the incidence of cancer is increasing in Korea. Cancer registration and cancer screening are important cancer control programs that are closely related to and influenced by each other.

The hospital-based cancer registry started in 1980 with 47 training hospitals participating in the cancer control program in Korea. Currently, the registry includes 80-90% of cancer cases from more than 150 training hospitals. The details of the history, objectives, and activities of the Korea Central Cancer Registry (KCCR) have been documented in 2005 and 2011.1,2

Cancer cases are classified according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3)3 and then converted according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10).4 As discussed in our first proposal,5 the roles of pathologists are important for improving the quality of cancer statistics since they provide a correct diagnosis and classification of the cancer which is essential for the application of the ICD-O code, in particular the behavior code. In collaboration with the National Cancer Center, the Korean Society of Pathologists (KSP) has participated in confirmation of diagnostic terms, standardization of diagnostic formats, clarification and assessment of multiple primaries, primary sites and the ICD-O code, and education of the pathologists. In addition, the KSP has also contributed to the education of cancer registrars because they play a key role in entering the data in the cancer registry. We have previously noticed the differences in the diagnostic terms between pathologists and the ICD-O code book. It is likely that these differences may originate from numerous coexisting classification systems, synonyms, new entities, newly recognized tumor behavior, and time interval between identification of an entity and its application to the code book. Of these, clarification of the behavior code is important for the registry, because behavior code 2 (carcinoma in situ) and 3 (invasive carcinoma and sarcoma) must be registered and used for both cancer statistics and insurance reimbursement. It is noteworthy, however, that some tumors including microinvasive tumors of the breast and ovary are not included in the ICD-O code book.3 The Gastrointestinal Pathology Study Group of the KSP therefore proposed behavior codes for several gastrointestinal tumors in 2008.5 Whether a microinvasive tumor (especially diagnosed as ductal carcinoma in situ with microinvasion [DCISM]) of the breast should be treated as carcinoma in situ or invasive carcinoma has been an important issue. The behavior of microinvasive tumors remains undetermined. Therefore, there is a controversy regarding this matter even among specialists.6-14 In addition, some clinicians and pathologists don't have exact concept about this matter. Furthermore, there is even a controversy regarding how to abbreviate microinvasive tumor into DCISM or microinvasive carcinoma (MIC) between the pathologists. This poses a problem to the registrars when they should enter the data in the cancer registry. An appropriate behavior code can be assigned only when they understand the meaning of different pathologic terminology. It would therefore be necessary not only to standardize the pathologic terminologies but also to have an identical understanding of the biologic behavior of the tumor, which is essential for the registration of tumors. In addition, borderline serous or mucinous tumors are issues that remain unresolved in association with diagnostic criteria, diagnostic terminology, behavior and treatment.15-21 We have therefore made an additional proposal of behavior codes for microinvasive tumors of the breast and ovary based on our previous proposal. In addition, we have also focused on the clinically meaningful behavior code rather than diagnostic criteria.

Given the above background, we made our second proposal. But this is not conclusive but subject to alterations with the accumulation of more experience and knowledge. However, reconsideration and understanding of the biological behavior of microinvasive tumors of the breast and ovary and sharing a common concept will be helpful in statistics and in changing after amending the rule. Thus, we would like to report a current progress on our second proposal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

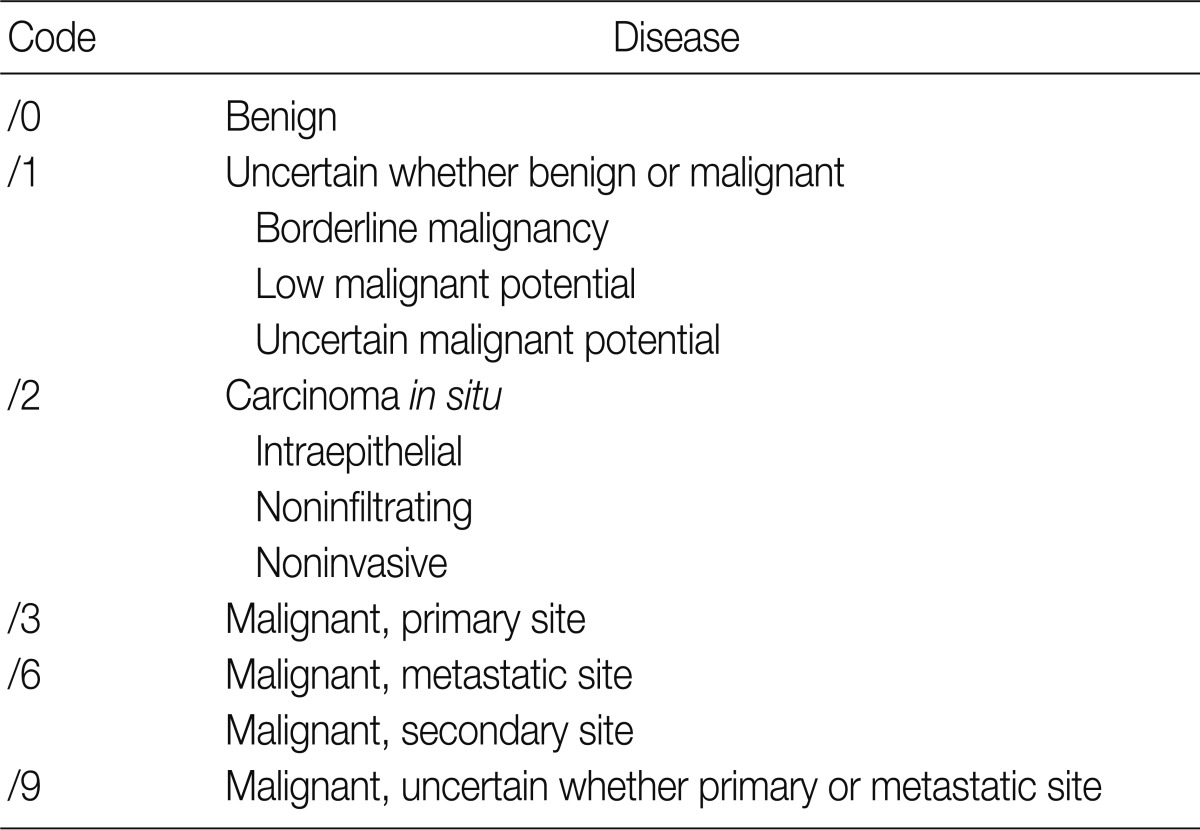

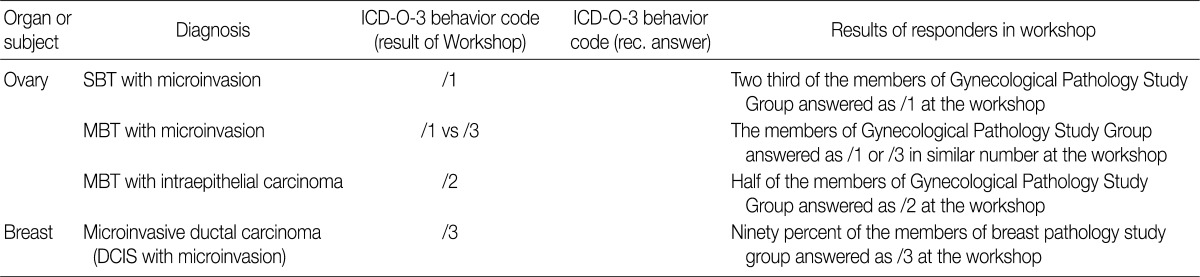

The ICD-O is composed of five digits; the first four digits represent the morphology code and the last one does biological behavior code ranging from benignity to malignancy (Table 1). To create a guideline for behavior codes, we selected issuable tumors, such as microinvasive tumors of the breast and ovary. To select topics, two members of the Breast Pathology Study Group and the Gynecological Pathology Study Group of the KSP presented their opinions regarding the behavior code with a list of references and a rationale. This was followed by the discussion and a convergence of opinion in the workshop held within the conference of the Breast Pathology Study Group, the Gynecological Pathology Study Group and the Cancer Registration Committee of the KSP. At the 2008 Autumn Congress of the KSP, each KSP member was asked to complete a questionnaire sheet comprising ICD-behavior codes (Table 2). Finally, provisional behavior codes were proposed for the selected tumors.

RESULTS

Microinvasive tumors of the breast

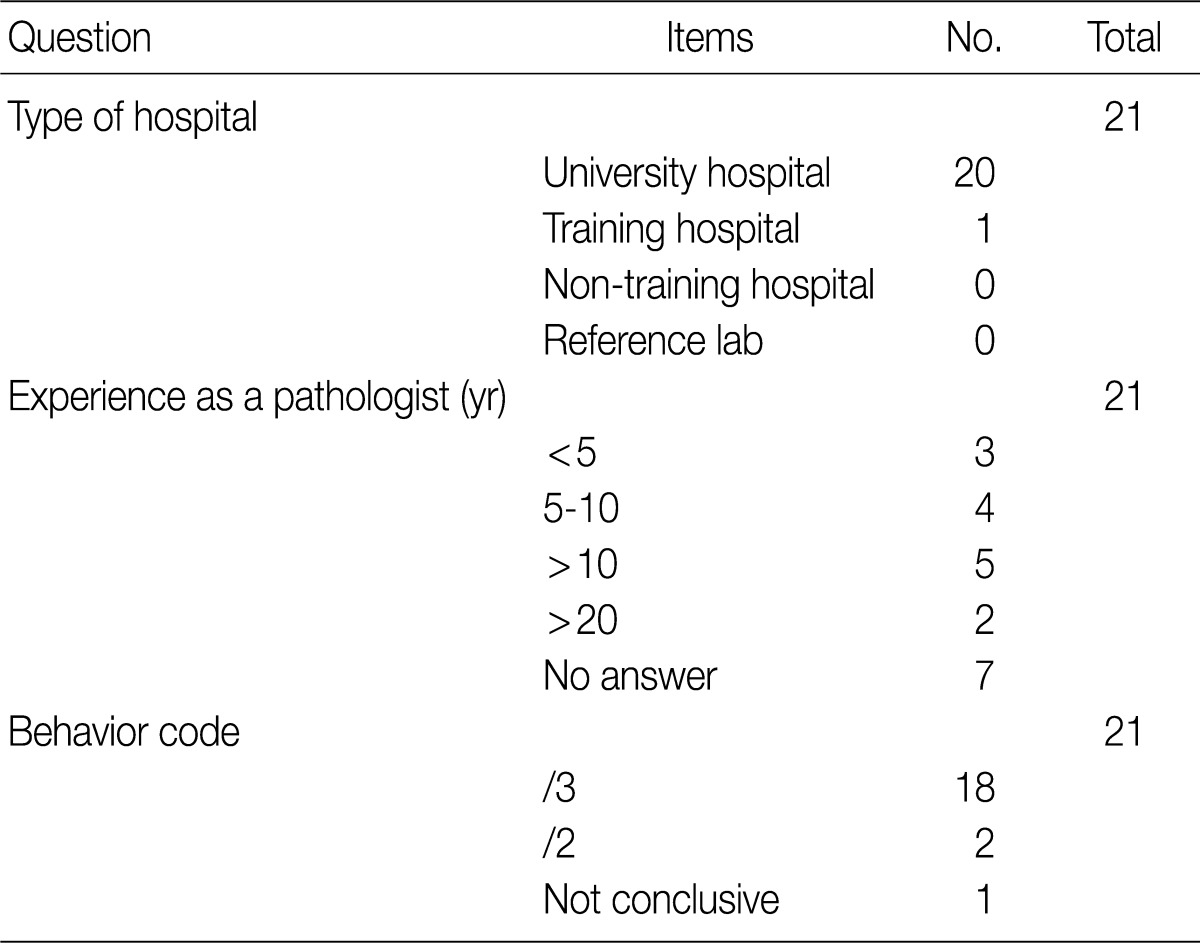

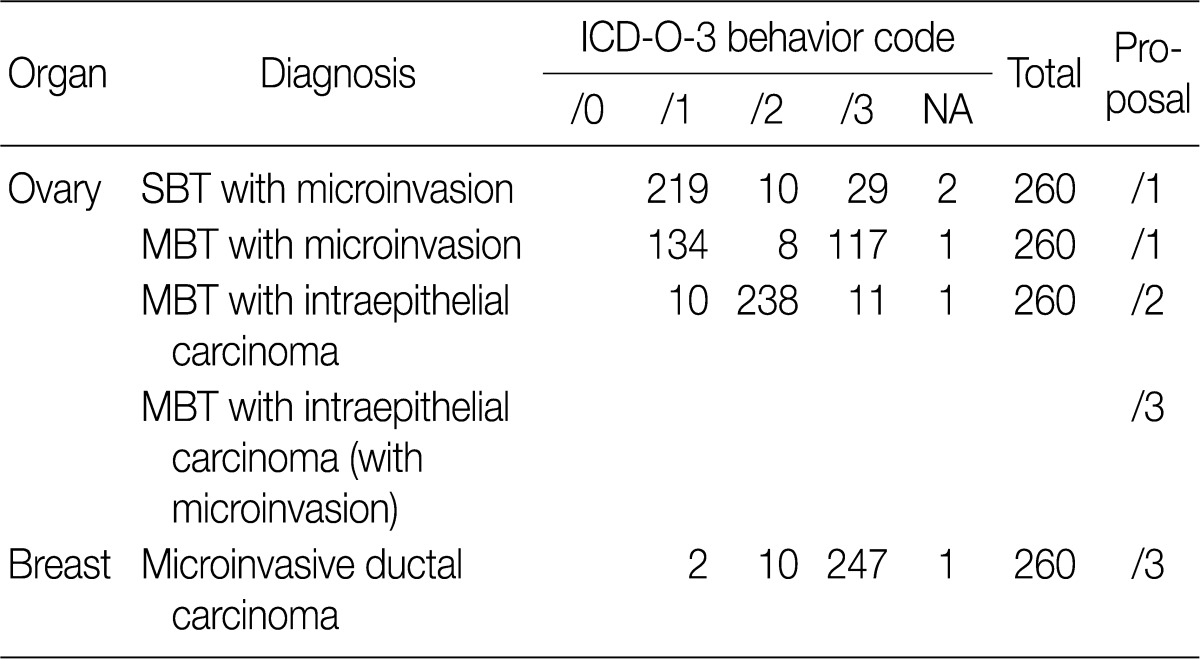

Based on workshop and a questionnaire survey, members of the Breast Pathology Study Group and those of the KSP drew a conclusions that microinvasive tumors or DCISM of the breast are an invasive form of carcinoma, which should be termed as MIC, and they should be differentiated from ductal carcinoma in situ and then be registered as an invasive carcinoma (/3) with the ICD-O code M8500/3 (study group members, 18/20; KSP members, 247/260) (Tables 3, 4).

Microinvasive tumors of the ovary

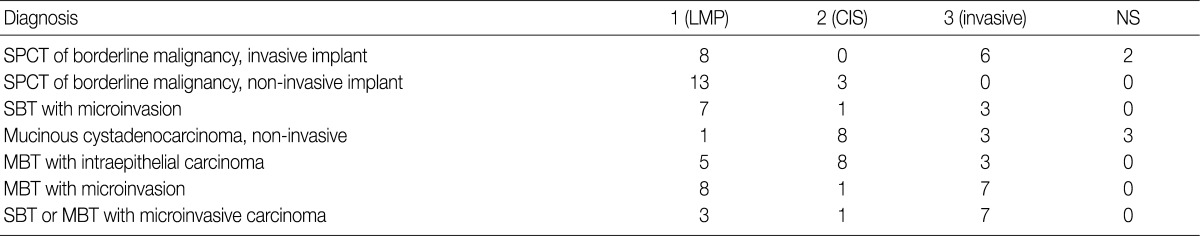

In the workshop, there was a diversity of the responses on behavior code of microinvasive tumor between members of Gynecological Pathology Study Group (Table 5). According to a questionnaire survey based on the workshop, however, serous borderline tumors (SBT) with microinvasion were regarded as borderline tumors (/1) with the ICD-O code M8442/1. The mucinous borderline tumors (MBT) with microinvasion, where the cellular components were not carcinomatous, were registered as borderline tumors (/1) with the ICD-O code M8472/1. In addition, the MBT with intraepithelial carcinoma were registered as carcinoma in situ (/2). Therefore, the MBT with microinvasion, composed of carcinomatous cells were registered as invasive carcinoma (/3) with the ICD-O code M8470/3 (Tables 4, 5).

DISCUSSION

Microinvasive tumors of the breast

Concerning the breast cancer registration program, whether microinvasive tumors should be treated as carcinoma in situ or invasive carcinoma is an important issue. In addition, diagnostic terms of the microinvasive tumors are used as DCISM or MIC. When the cancer registrars encounter with DCISM, they might confuse the disease entity with its behavior. The definition of microinvasion in ductal and lobular carcinoma and their behavior are not clearly defined and varies between the authors.6-10 For example, microinvasion is defined in several different way, such as: 1) invasive focus is too small to grade; 2) invasive focus <10%; 3) invasive focus <0.2 cm; and 4) invasive focus <0.1 cm. The rate of axillary lymph node metastasis was varied from 0% to 20% and follow-up data was also varied from no further recurrence during 11 years to death.6-10

This poses a diagnostic challenge to pathologists. But Silver and Tavassoli10 performed a review of lieratures and thereby reported that MIC should be treated differently from carcinoma in situ based on its clinical behavior including the lymph node metastasis. But this has not been confirmed but remains controversial, which is due to a variability in the definition of microinvasion between the authors. Since the publication of the 5th edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cancer staging manual in 1997,22 the AJCC defined MIC as follows:

Microinvasion is the extension of tumor cells beyond the basement membrane into the adjacent tissues with no focus >0.1 cm in the greatest dimension

When there are multiple foci of microinvasion, the size of the largest focus is used to classify the microinvasion (do not use the sum of all individual foci)

Presence of multiple foci should be noted and/or quantified, as with multiple larger invasive carcinomas.

These criteria for definition of MIC resolved the diagnostic problems. Thus, most of the pathologists now follow the AJCC cancer staging manual guidelines. The behaviors of microinvasive tumors remain inconclusive, for which many controversial opinions exist. De Mascarel et al.11 showed that MIC exhibits distant metastases (2.8%) and death due to breast cancer (1.4%; same as DCIS) within ten years. Padmore et al.12 showed that only one of 11 patients suffered local recurrence of MIC and these patients had no further recurrence eight years later although there was a lung metastasis in one of them who had DCIS with the greatest dimension of 8 cm and 17 microinvasive foci. Yang et al.13 reported that all of their patients they studied had negative lymph nodes, 3.5% of whom did a family history of breast cancer. In addition, these authors also noted that 54% of the cases were human epidermal growth factor (HER2)/neu-positive and 40% were estrogen receptor- and progesterone receptor-negative. These authors showed that the behavior of MIC was similar to the DCIS. Zavagno et al.14 reported that axillary involvement was found in 7.5% of patients with MIC who were treated with axillary lymph node dissection and 14.3% of those who were treated with a sentinel node biopsy. These results indicate that there is a difference in the clinical behavior between MIC and DCIS. In AJCC cancer staging manual22 MIC was categorized as invasive carcinoma (T1). However, the World Helath Organization (WHO) tumor classification did not have an ICD-O code for MIC, on the ground that MIC is not generally accepted as a tumor entity and more evidence and follow-up data are needed for adjusting the code.23 Furthermore, in the Rosen's textbook for breast pathology,24 MIC is included in the chapter of intraductal carcinoma. We have therefore speculated not only that it would be clinically meaningful to collect opinions about the biological behavior of MIC but also that it would be of help for statistics to share common concepts. This is why we consider an microinvasive tumor as an issue although MIC was considered more as an invasive carcinoma according to the AJCC guidelines. Based on these results, members of the Breast Pathology Study Group and members of the KSP drew the proposal as follows:

Microinvasive tumors (MIC or DCISM) of the breast are an invasive form of carcinoma

They should be designated as MIC

They should be differentiated from ductal carcinoma in situ

They should be registered as an invasive carcinoma (/3) with the ICD-O code M8500/3 (study group members, 18/20; KSP members, 247/260) (Tables 3, 4).

Microinvasive tumors of the ovary

Every carcinoma has its own definition depending on the histological type. The behavior of the microinvasive tumors of the ovary also varies depending on the histological type. Moreover, the classification of malignant ovarian tumors has undergone changes with the advances in understanding of molecular pathogenetic mechanisms. In the current proposal, we focused on the two most common ovarian tumors; serous and mucinous types.

In 1973, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) and WHO defined the diganostic criteria of ovarian carcinoma as a tumor with a destructive stromal invasion within the primary ovarian tumor and a borderline tumor as a tumor without a destructive stromal invasion.25 However, this general definition cannot be commonly applied to all histological types of ovarian carcinoma. Therefore, each type of ovarian carcinoma has its own diagnostic criteria.

Ovarian serous tumor is generally classified as a benign serous tumor, SBT and serous carcinoma. SBT is defined as a tumor showing one or more cysts with polypoid excrescences, glands and closely packed papillae that are lined by stratified cuboidal to columnar epithelial cells without a frank stromal invasion. The degree of nuclear atypia of the epithlelial cells varies from mild to moderate, which is the different feature from carcinoma in situ.25,26

Ovarian serous carcinoma is defined as a tumor having a destructive stromal invasion regardless of the presence of extraovarian tumor implants or lymph node metastasis.16 A tumor showing a stromal invasion of less than 3-5 mm without a desmoplastic reaction has been designated as a microinvasive tumor.15 Microinvasion is described in the borderline tumor category as one of the associated features while dealing with SBT.26 Microinvasion can be found in otherwise typical SBT and these microinvasive tumors have similar biologic behaviors and prognosis to those of tumors lacking this feature.15-18,26 Accordingly, SBTs with microinvasion should be distinguished from serous carcinoma. The latter means that serous tumors exhibit definite destructive stromal invasion.

SBTs with micropapillary features are known to be frequently associated with extraovarian implants, tumor recurrences, and tumor-related deaths. It has also been described that 50-60% of patients with non-invasive low-grade micropapillary serous carcinoma have cancer-associated deaths after a long-term follow-up.27 Therefore, there is an increasing consensus that it should be regarded as a carcinoma despite a lack of evidence of destructive stromal invasion.27 However, this is not a well-accepted viewpoint by most investigators.26 Therefore, further investigation is warranted to resolve this issue.

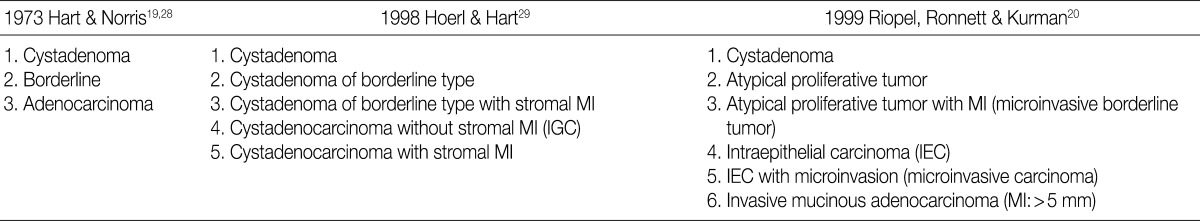

There is a difference in the definition between the carcinoma in ovarian mucinous tumors and the ovarian serous tumors. In addition, there is also a difference in the clinical significance between the microinvasive tumor in ovarian mucinous tumors and the ovarian serous tumors. Although FIGO and WHO defined carcinoma as a tumor having destructive invasion,25 Hart and Norris added several histologic criteria for the mucinous type, and these include, more than four layers of epithelium, presence of back-to-back arrangement or cribriform pattern, and the presence of severe nuclear atypia, thus termed as Hart and Norris criteria.19,28 However, it is well known that significant interobserver disagreement exists using these diagnostic criteria. Subsequently, new diagostic criteria have been proposed by Hoerl and Hart29 and Riopel et al.,20 which are most commonly used in place of WHO and FIGO classification (Table 6). A cribriform pattern or back-to-back arrangements have not been mentioned as diagnostic criteria of carcinomas. It is quite confusing that these classification systems use the term "microinvasion" even in the category of borderline tumors. Thus, many tumors that have been classified as carcinomas have been revised to borderline tumors, while some carcinomas have been re-classified into the MBT with microinvasion or intraepithelial carcinomas.20,29 The most important change was in the concept of stromal microinvasion in the mucinous tumor.29,30 The definition of microinvasion in mucinous tumors was the presence of one or several tumor cell clusters or that of invasive irregular glands with an ill-defined margin. But there is no consensus existed regarding the degree of cytologic atypia and the size of the microinvasive lesion. Despite an incomplete consensus, many authors suggest that significant cellular atypia as well as the size of the invasive foci are required for the diagnosis of MIC.21,26 We have a consensus on many authors' opinion that the presence of significant cellular atypia is a requisite for the diagnosis of MIC. This is because the presence of microinvasive foci composed of only low grade nuclear atypia (MBT with microinvasion) does not alter the favorable prognosis of the otherwise typical MBT.20,26 In addition, irregularly marginated cellular clusters can also be seen in the stroma in association with mucin granulomas, which are frequently formed in MBT. This explains why MBT with microinvasion should be distinguished from MIC. MBT with intraepithelial carcinoma can be defined as MBT exhibiting areas of four or more epithelial cell layers, scattered foci of cribriform or stroma-free papillary architecture, and most importantly, moderate or severe atypical nuclei.26 Moreover, the presence of microinvasive component and the adjacent glands containing severe atypical nuclei, should result in the diagnosis of an MIC.26 This led to a conclusion that MBT with intraepithelial carcinoma with microinvasion by severely atypical carcinoma cells should be diagnosed as MBT with MIC. But this was not confirmed on a questionnaire survey. Based on these tentative conclusions, we can propose that not only MBT with microinvasion, whose cellular constituents are not severely atypical, should be regarded as borderline tumors (/1), but also that those whose cellular constituents are severely atypical (carcinomatous), should be regarded as MBT with MIC (/3).

In the workshop, there was a diversity of the responses on behavior code of microinvasive tumor between the members of Gynecological Pathology Study Group. According to a questionnaire survey based on the KSP workshop, however, the responses were more integrative and conclusive. Thus, based on these results, members of the Gynecological Pathology Study Group and the KSP drew the proposal as follows:

SBT with microinvasion should be regarded as borderline tumors (M8442/1)

MBT with microinvasion should be regarded as borderline tumors with behavior code /1 (M8472/1)

MBT with intraepithelial carcinoma should be regarded as carcinoma in situ (/2)

MBT with microinvasion by carcinomatous cells (MBT with MIC) should be regarded as invasive carcinoma with behavior code /3 (M8470/3) (Tables 4, 5).

We have not reached conclusive and precise definitions for the diagnostic criteria and behavior codes, but the above proposal will be used as another reference that is subject to alterations upon further analysis and feedback in the future. Our results demonstrate great merit in improving the quality of cancer registration and cancer control programs. In addition, we'll also continue to make efforts to develop and improve guidelines for more tumors in the future.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the members of the Breast Pathology Study Group, the Gynecological Pathology Study Group, and the Cancer Registration Committee of the KSP for participating in the workshop and all members of the KSP for responding to a questionnaire survey.

This study was supported by a grant from the Management Center for Health Promotion of NCC in 2008.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.