Pulmonary Nodular Lymphoid Hyperplasia with Mass-Formation: Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Nine Cases and Review of the Literature

Article information

Abstract

Background

Pulmonary nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (PNLH) is a non-neoplastic pulmonary lymphoid disorder that can be mistaken for malignancy on radiography. Herein, we present nine cases of PNLH, emphasizing clinicoradiological findings and histological features.

Methods

We analyzed radiological and clinicopathological features from the electronic medical records of nine patients (eight females and one male) diagnosed with PNLH. IgG and IgG4 immunohistochemical staining was performed in three patients.

Results

Two of the nine patients had experienced tuberculosis 40 and 30 years prior, respectively. Interestingly, none were current smokers, although two were ex-smokers. Three patients complaining of persistent cough underwent computed tomography of the chest. PNLH was incidentally discovered in five patients during examination for other reasons. The remaining patient was diagnosed with the disease following treatment for pneumonia. Imaging studies revealed consolidation or a mass-like lesion in eight patients. First impressions included invasive adenocarcinoma and mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue‒type lymphoma. Aspergillosis was suspected in the remaining patient based on radiological images. Resection was performed in all patients. Microscopically, the lesions consisted of nodular proliferation of reactive germinal centers accompanied by infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages in various degrees and surrounding fibrosis. Ultimately, all nine patients were diagnosed with PNLH and showed no evidence of recurrence on follow-up.

Conclusions

PNLH is an uncommon but distinct entity with a benign nature, and understanding the radiological and clinicopathological characteristics of PNLH is important.

Non-neoplastic pulmonary lymphoproliferative disorders include nodular lymphoid hyperplasia, follicular bronchiolitis, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia, Castleman’s disease, and intrapulmonary lymph node [1-3]. The term “pseudolymphoma” was initially proposed in 1963 by Saltzstein [4] in his study on pulmonary lymphoid lesions. Kradin and Mark [5] later suggested the term “pulmonary nodular lymphoid hyperplasia” (PNLH). Abbondanzo et al. [6] also suggested that PNLH consisted of reactive pulmonary lesions ranging from follicular hyperplasia to diffuse hyperplasia of the bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue [7].

On microscopy, PNLH is composed of reactive nodular lymphoid proliferation that forms one or more pulmonary masses [2,6-8]. However, the other lymphoproliferative lesions mentioned above should be considered, especially malignant lymphomas. Diagnosis can be made using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of slides with the addition of immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for CD3, CD20, and Ki-67. If necessary, kappa and light chain IHC staining and/or an immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) gene rearrangement test can be performed in cases with polyclonal results [6-9].

PNLH is a benign, reactive, and uncommon lesion [6,7,10]. In the present study, the histopathological features and radiological findings in the resected lungs of nine patients diagnosed with PNLH were evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case selection and clinical data

The electronic medical records of Samsung Medical Center were searched for lung specimens of patients diagnosed with PNLH between January 2012 and September 2017. We excluded lymphoid interstitial pneumonia and other lymphoproliferative disorders that were not nodular or reactive. Clinical characteristics of patients were also retrieved from the electronic medical records, including age, sex, chief complaint, past and/or current history, smoking history, and radiological findings. The present study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Samsung Medical Center (IRB No. 2017-10-055-011). Formal written informed consent was not required and was waived by the IRB.

Pathological evaluation

Two pathologists (J. Han and J. Sim) reviewed the slides of selected cases. Primary malignant lymphomas and other lymphoproliferative lesions were excluded. IHC staining with CD3 (A0452, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), CD20 (L26, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), and Ki-67 (MIB-1, Dako) was performed in all cases. BCL2 (124, Dako), BCL6 (LN22, Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), and kappa and lambda light chain (Dako) IHC staining was performed in only one patient who showed a diffuse pattern (case 6). Additionally, the IgG4:IgG ratio was assessed using IgG (Dako) and IgG4 (MRQ-44, Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA, USA) antibodies in only three cases which showed plasma cell infiltration (cases 1, 2, and 6). Special staining was performed to confirm the presence of microorganisms. Molecular tests such as IgH gene rearrangement test were not performed in any case.

RESULTS

Clinical and radiological findings

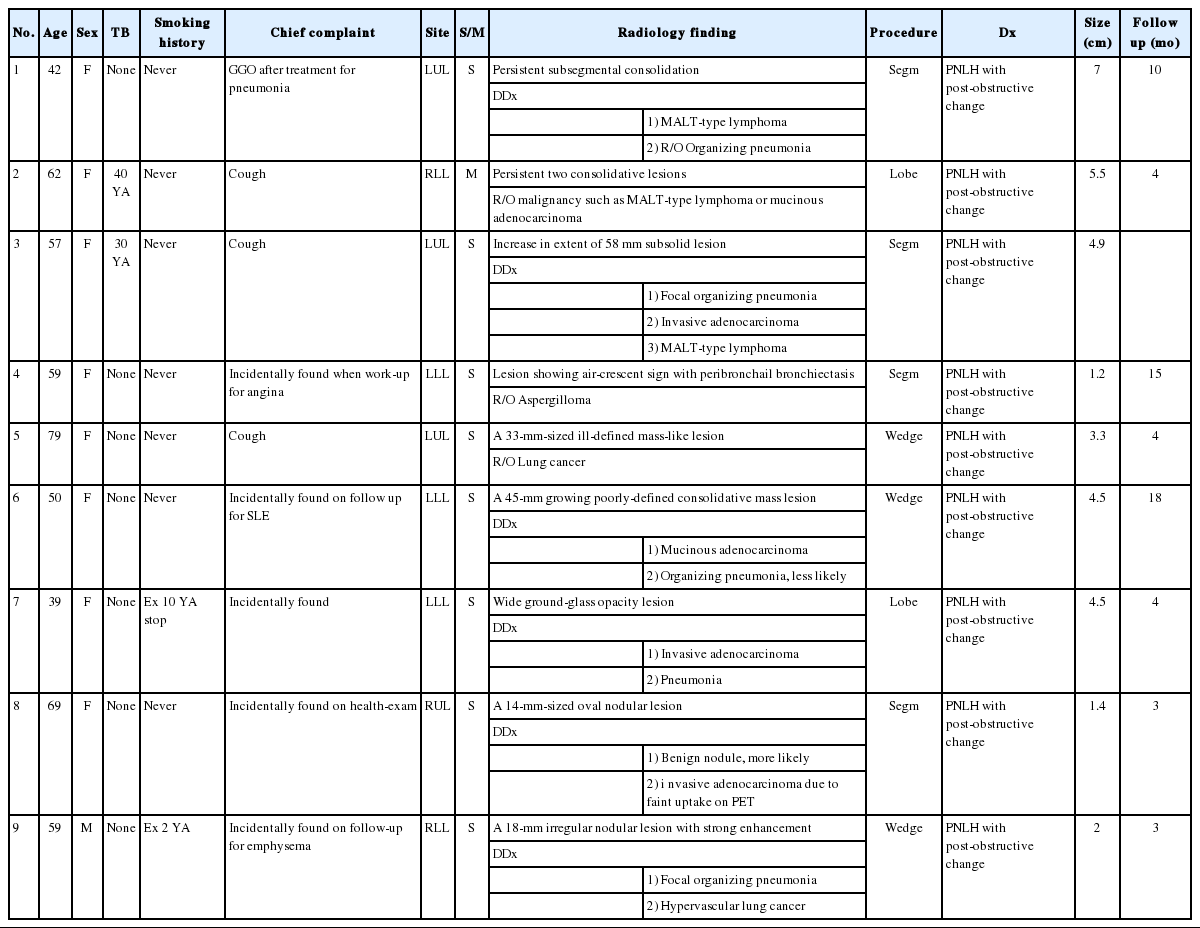

Table 1 shows the clinicopathological characteristics of the nine patients (eight females and one male). The mean age was 57.3 years (range, 39 to 79 years). Two patients (patients 2 and 3) had a history of tuberculosis 40 and 30 years prior, respectively. Seven patients had never smoked, and the other two patients were ex-smokers who stopped smoking 20 and 2 years prior, respectively; none of the patients were current smokers. Three patients were diagnosed with cough symptoms, and five were accidentally discovered during an examination for other reasons, including angina, emphysema, health examination, and systemic lupus erythematosus. The remaining patient was identified after treatment for pneumonia. Only one patient (patient 6) had several autoimmune antibody tests. Antinuclear antibody titer was 1:40 with a nuclear pattern. Negative results were obtained for several autoimmune antibodies, including anti-Sjogren’s syndrome A, anti-Sjogren’s syndrome B, anti-ribonucleoprotein, anti-Sm, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. The lesions were solitary in eight patients and multiple in one patient (patient 2). Most radiological findings were persistent and/or slow-growing consolidation lesions (Fig. 1). In eight patients, the possibility of primary lymphoma or primary lung cancer was suspected based on radiological findings. One patient (patient 4) was suspected of aspergilloma based on radiological images. Recurrence, previous disease, or new lesions were not observed in any patient during the 3–18 months of radiological follow-up.

Radiological images (chest computed tomography) of three patients before surgery. (A) Image from patient 3 shows the extent of a 58-mm subsolid lesion in the lingular division of the left upper lobe. (B) Image from patient 7 shows a wide ground-glass opacity lesion in the superior segment of the left lower lobe. (C) Image from patient 9 shows an 18-mm irregular nodular lesion with strong enhancement in the posterior basal segment of the right lower lobe.

Pathological features

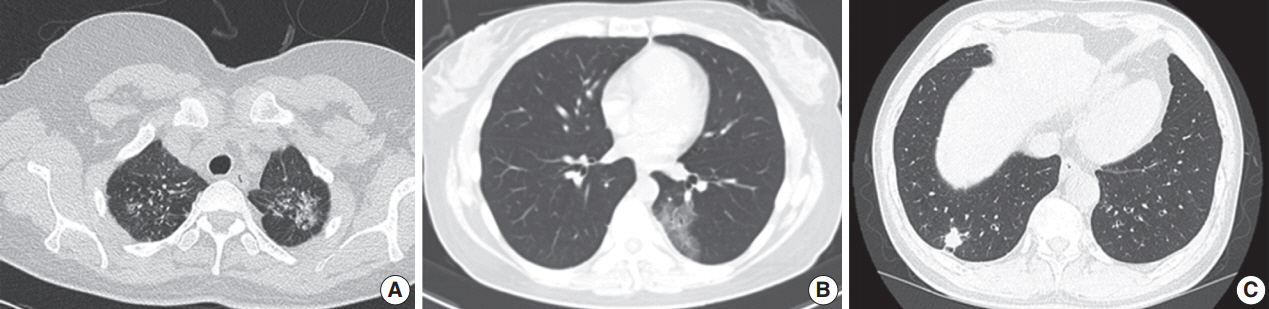

Although gross images were not available in four patients, softto-firm and well-circumscribed lesions were observed in most cases on gross examination. An infiltrative mass-like lesion mimicking invasive lung cancer was observed on one image (Fig. 2A). The remaining four patients showed a relatively well-defined lesion with soft-to-firm consistency (Fig. 2B).

Gross findings of pulmonary nodular lymphoid hyperplasia. (A) Gross image from patient 3 shows a relatively well-circumscribed grayish-white mass-forming lesion with firm consistency. (B) Gross image from patient 7 displays a well-defined lesion with soft-to-firm consistency

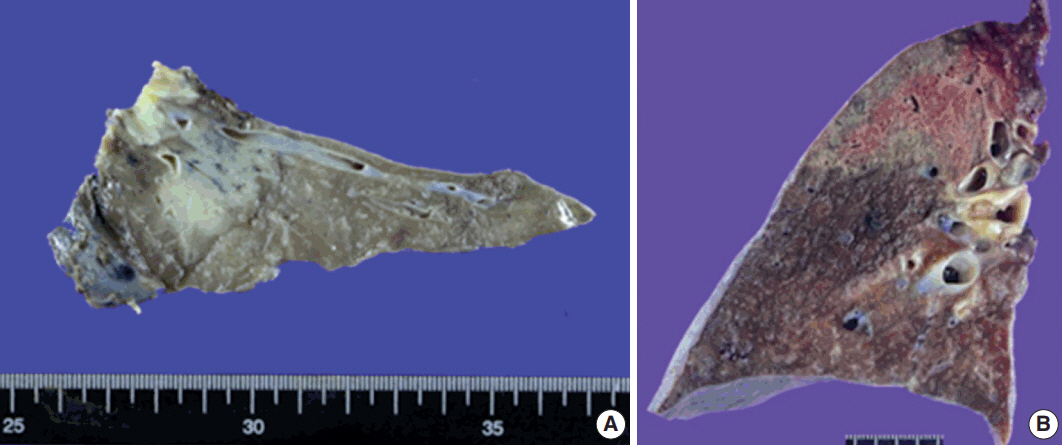

Based on microscopy, the lesions were relatively well-defined with a nodular pattern. Although six of nine patients had well-marginated and regular borders (Fig. 3A), three had a relatively well-demarcated, irregular borders (Fig. 3B). Four cases showed a nodular pattern (Fig. 3B), and the other five showed a mixed diffuse and nodular pattern (Fig. 3C, D). Each lesion was composed of polymorphous lymphoid cells, reactive germinal centers, and infiltration of a variety of neutrophils, plasma cells, and macrophages without a carcinoma component. No Dutcher bodies or invasion of the pleura were present in any case. In addition, three cases showed moderate neutrophilic infiltration with a few macrophages. In contrast, moderate to marked infiltration of macrophages with rare neutrophilic infiltration was observed in five cases. The remaining one showed marked infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages. The degree of fibrosis was variable. Three cases showed rare or mild fibrosis (Fig. 3A, B), and the remaining six displayed moderate to marked fibrosis (Fig. 3D). However, the pattern of fibrosis was not storiform in any case. Obliterative arteritis or phlebitis suggesting IgG4-related disease was not detected in any patient. The amount of plasma cell infiltration also varied from scattered to dense. The plasma cell infiltration was in a scattered pattern in three cases and moderate to marked in six cases (Fig. 3E). Two patients had mild lymphoepithelial lesions which were not extensive or destructive (Fig. 3F). Microscopic features are summarized in Table 2.

Histopathological features on hematoxylin and eosin slides of pulmonary nodular lymphoid hyperplasia. (A) In patient 2, a well-circumscribed lesion was observed. The lesion consisted of reactive germinal centers with septal fibrosis, moderate infiltration of neutrophils, and a few macrophages. (B) In patient 4, the lesion was relatively well-defined with irregular borders and rare fibrosis. The lesion was composed of reactive germinal centers with marked infiltration of macrophages. A fungal ball was present in the bronchus at the upper portion of the image and was confirmed using Grocott's methenamine silver stain and Periodic acid–Schiff stain (not shown). (C) In patient 6, the lesion was composed of scattered reactive germinal centers with moderate infiltration of macrophages. No fibrous septum was present. (D) In patient 5, a relatively well-demarcated lesion with irregular border was observed. The lesion consisted of a few reactive germinal centers with fibrosis and marked infiltration of macrophages. (E) In patient 4, the lesion showed moderate infiltration of plasma cells between germinal centers. However, storiform fibrosis or obliterative phlebitis was not detected. (F) Patient 1 showed a mild form of lymphoepithelial lesion. However, the lesion was not extensive or destructive, suggesting extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue.

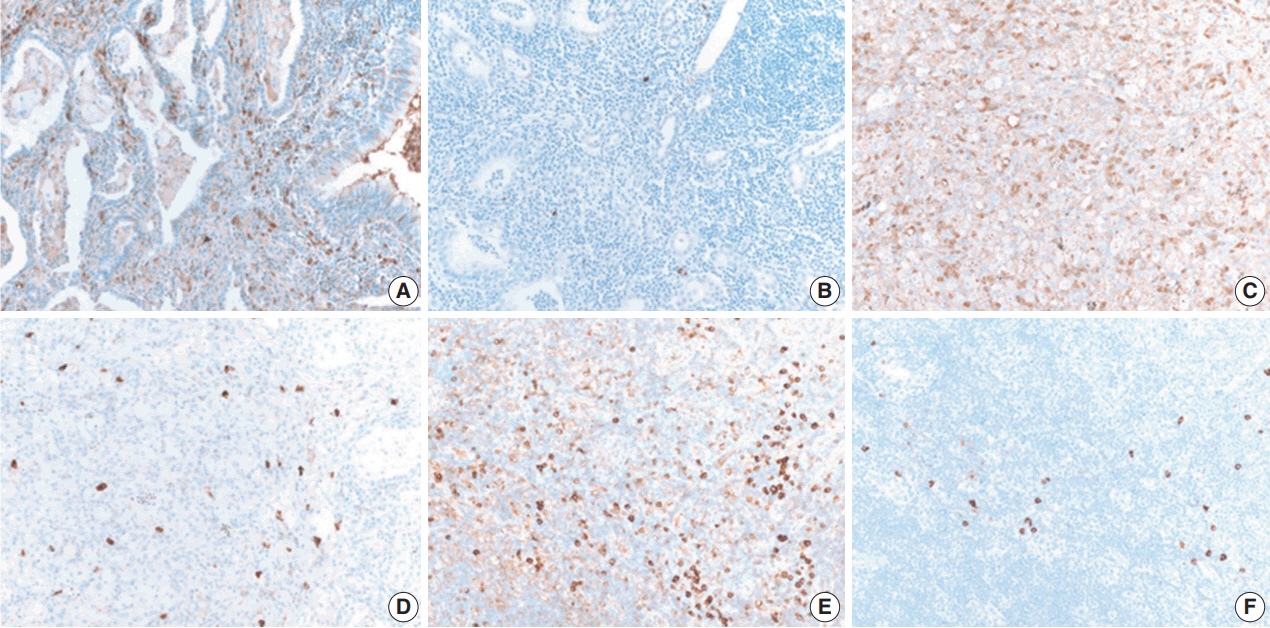

IHC staining for B cells showed numerous B cells within reactive follicles in all cases (Fig. 4A). IHC staining for CD3 displayed many T cells in interfollicular areas and occasional T cells within reactive follicles (Fig. 4B). A high proliferative activity (Ki-67 index) was observed in reactive follicles (Fig. 4C), dividing dark and light zones. Although two cases showed a diffuse pattern, diffuse B-cell infiltration which is a characteristic of extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)-type lymphoma was not identified by CD3 and CD20 IHC staining (Fig. 4D, E). Additionally, BCL2 and BCL6 IHC staining confirmed inter-follicular lymphoid cells and germinal centers (Fig. 4F, G). Moreover, kappa and lambda light chain IHC staining did not reveal any monoclonality (Fig. 4H, I).

Immunohistochemical (IHC) results of pulmonary nodular lymphoid hyperplasia. IHC staining using CD20 (A) and CD3 (B) showed that the lesion in patient 2 had several well-preserved germinal centers with mixed inter-follicular T-cells. (C) Ki-67 IHC staining showed high proliferative activity in the germinal center. IHC staining using CD3 (D) and CD20 (E) showed an inter-follicular T-cell zone and germinal center in the lesion in patient 6, confirming a diffuse pattern. (F, G) Additionally, the inter-follicular and germinal centers were IHC stained with BCL2 and BCL6. (H, I) IHC staining of kappa and lambda light chains indicated a polyclonal population.

Thus, PNLH was diagnosed as such. In all patients, molecular tests such as IgH gene rearrangement test were not required to differentiate malignant lymphomas. Patient 4 showed an aspergillus species that was confirmed by Grocott’s methenamine silver stain and periodic acid–Schiff stain (not shown). The IgG4:IgG ratio was less than 0.2 in three patients, which was not compatible with IgG4-related disease (Fig. 5).

IgG4:IgG ratio of pulmonary nodular lymphoid hyperplasia. The IgG4:IgG ratio varied in this study. The ratio in case 1 was less than 0.1 (A, IgG; B, IgG4). The ratios in case 5 (C, IgG; D, IgG4) and case 6 (E, IgG; F, IgG4) were approximately 0.1–0.2, which is not compatible with IgG4-related disease.

DISCUSSION

We reviewed clinicopathological features of nine PNLH patients. Based on radiological findings, eight patients were suspected to have a malignancy such as adenocarcinoma or MALT-type lymphoma, and one showed a solid mass-forming lesion on gross examination. However, histological findings on H&E staining showed benign reactive lesions. Non-extensive lymphoepithelial lesions were present in two patients. However, extensive lymphoepithelial lesion, Dutcher bodies, or pleural invasion were not observed. Additional IHC staining for CD3, CD20, and Ki-67 showed no evidence of malignancy. Only one case showed a diffuse pattern; additional staining was required to distinguish the lesion from MALT-type lymphoma. IHC staining of kappa and lambda light chain indicated a polyclonal population. Molecular testing such as IgH gene rearrangement test was not performed in any case.

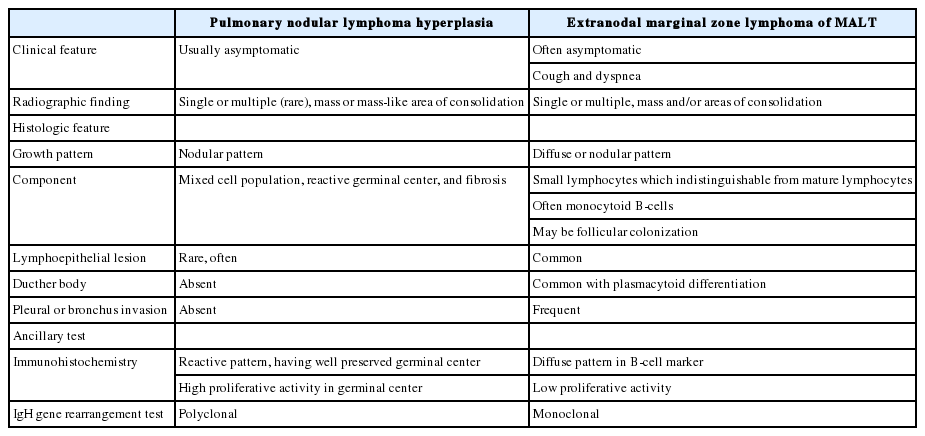

PNLH is usually asymptomatic and in most cases is found incidentally during examination for other reasons. As mentioned above, PNLH is a benign lesion typically diagnosed histologically using H&E-stained slides [2,3,6,9]. Based on histological analysis, PNLH is composed of reactive germinal centers with a nodular pattern and is mainly located in the subpleural area. Fibrosis and infiltration of other inflammatory cells are variable. Lymphoepithelial lesions with lymphocytes infiltrating the bronchial epithelium can occur [10]; however, no pleural or bronchus invasion is observed [6,10]. Although presence of a single lesion is common, the clinical course of solitary and multiple lesions is similar. Based on radiological findings, PNLH appears as a consolidation or mass-like lesion and cannot be easily distinguished from lung cancer or malignant lymphoma, especially when the size increases during follow-up [7]. Differential diseases include lymphoid interstitial pneumonia, follicular bronchitis, and MALT-type lymphoma [2,8,9,11]. Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia infiltrates the lungs as a whole and does not form a germinal center. MALT-type lymphoma also presents with a diffuse pattern with monotonous lymphoid cells. Dutcher bodies, pleural invasion, and bronchus invasion are common in MALT-type lymphoma. IHC staining and/or IgH gene rearrangement test indicate a monoclonal population. The key features of PNLH and MALT-type lymphoma are summarized in Table 3.

Key features of pulmonary nodular hyperplasia and extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)

In 2000, Abbondanzo et al. [6] reported clinicopathological features of 14 patients with PNLH. They demonstrated that PNLH was mainly asymptomatic, incidentally found on radiological imaging or due to complaints of cough, and often observed as a mass on radiological imaging. Although most patients presented with a single mass smaller than 3 cm, others were as large as 5 cm. Histological analysis showed that PNLH has germinal centers with a nodular pattern, sometimes accompanied by fibrosis. Lymphoepithelial lesions, pleural plaques, or bronchial cartilage involvement was not observed. However, Begueret et al. [10] demonstrated that PNLH could also have lymphoepithelial lesions. They further found the lymphoepithelial lesions in MALT-type lymphoma were CD20+/CD43+, in contrast to CD3+/CD43+ or CD20+/CD43– lesions in lymphoid hyperplasia. Moreover, they found no intralymphatic extension in lymphoid hyperplasia.

In 2013, Guinee et al. [12] reported that the number of IgG4-positive plasma cells was significantly higher in PNLH than in other lesions. Their study included six patients with PNLH, nine patients with MALT-type lymphoma, eight patients with intrapulmonary lymphoma, eight patients with follicular bronchitis, and four patients with lymphoid interstitial pneumonia. They demonstrated that the IgG4/IgG ratio in PNLH was significantly higher than in other lesions. Moreover, two of six PNLH patients had an IgG4/IgG ratio greater than 0.4. However, in 2017, Bois et al. [13] reported that the ratio in 26 PNLH patients was not higher than that in controls. The control group in their study included two patients with diffuse lymphoid hyperplasia without nodularity, five patients with usual interstitial pneumonia and increased lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, and two patients with thoracic lymphadenopathy. In addition, they found that PNLH had a low IgG4/IgG ratio that did not suggest IgG4-related disease and reported no evidence of Epstein-Barr virus infection. In our study, IgG and IgG4 IHC staining results were available in three patients. Similar to the previous results, there was no evidence of IgG4-related disease in those patients. Whether PNLH is associated with IgG4-related disease requires further evaluation with a greater number of patients.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) may be the first presentation of connective tissue diseases (CTDs); up to 15% of patients initially diagnosed with idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) have an underlying systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease upon further evaluation [14,15]. The most common histological pattern in patients with CTD is NSIP [14]. However, no evidence of ILD except PNLH was found in the systemic lupus erythematosus patient included in this study. Moreover, on radiological analysis, ILD was not evident. PNLH in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome was previously reported [16]. To determine whether PNLH is associated with CTD requires further studies with a larger cohort.

In addition, we observed that PNLH could have various degrees of fibrosis as well as neutrophil and macrophage. Patients with PNLH could possibly be diagnosed using some of the organizing pneumonia spectrum as a post-obstructive change due to mass formation. Moderate to marked infiltration of neutrophils with rare macrophage infiltration could represent a relatively early phase of organizing pneumonia, while numerous macrophages and surrounding fibrosis with rare neutrophil infiltration are more likely to indicate progression of organizing pneumonia.

In conclusion, we report a mass-like or consolidative lesion in nine patients with PNLH. Differential diagnosis of PNLH includes MALT-type lymphoma and other benign lymphoproliferative disorders. Although molecular tests were not performed, meticulous pathological examination can aid in diagnosing PNLH with confidence.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.