Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Extrahepatic Common Hepatic Duct

Article information

Abstract

We report a rare case of hilar squamous cell carcinoma. A 62-year-old Korean woman complaining of nausea was referred to our hospital. Her biliary computed tomography revealed a 28 mm-sized protruding solid mass in the proximal common bile duct. The patient underwent left hemihepatectomy with S1 segmentectomy and segmental excision of the common bile duct. Microscopically, the tumor was a moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct, without any component of adenocarcinoma or metaplastic portion in the biliary epithelium. Immunohistochemically, the tumor was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5/6, CK19, p40, and p63. Squamous cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct is rare. To date, only 24 cases of biliary squamous cell carcinomas have been reported. Here, we provide a clinicopathologic review of previously reported extrahepatic bile duct squamous cell carcinomas.

Cholangiocarcinoma is a malignant tumor arising from the biliary tree at any portion of the bile duct: from the bile ductules of the intrahepatic area to the ampulla of Vater. Most of the tumors are adenocarcinomas, and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the extrahepatic bile duct is rare. Since the first reported case by Cabot and Painter [1], about 24 cases of bile duct SCC have been reported in the literature [2-18].

Here, we review the clinicopathologic characteristics of the reported cases of biliary SCC.

CASE REPORT

Clinical summary

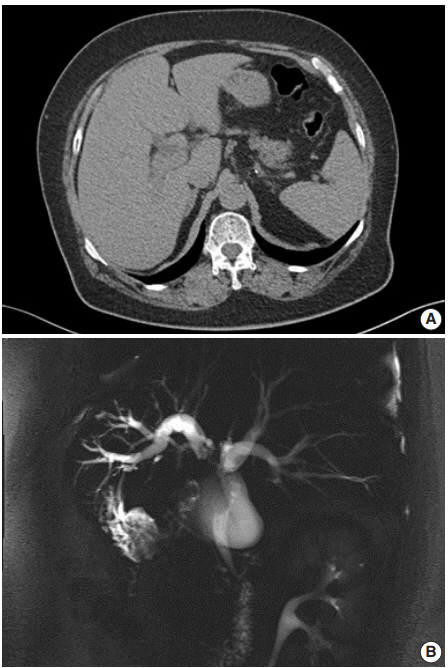

A 62-year-old Korean woman complained of continuous nausea and abdominal discomfort for two months. Except for the diagnosis of thyroid papillary carcinoma 13 years prior to presentation, she had no history of other malignancies or cholelithiasis. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) performed at a local clinic revealed a dilated bile duct (Fig. 1A). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed luminal narrowing in the distal bile duct with proximal dilation (Fig. 1B). Perihilar proximal biliary cholangiocarcinoma was suspected. Liver magnetic resonance images (MRI) showed a 1 cm-sized, non-enhancing, T2 high signal intensity lesion in the left lobe, suggesting hepatic cyst or abscess. Metastasis to the common hepatic artery, portocaval lymph node, and hepatic duct ligament was also suspected. Preoperatively, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-assisted biopsy was performed, and a diagnosis of carcinoma with squamous differentiation was rendered. Subsequently, left hemihepatectomy with S1 segmentectomy and segmental excision of the common bile duct were performed. After surgical resection, abdominal CT revealed an enlarged common hepatic arterial lymph node, resulting in suspicion of metastasis. The patient developed ascites and a pleural effusion. In addition, a thrombus developed in the superior vena cava. Heparin was used for treatment of thrombus; however, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia was followed. The patient received 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and cisplatin, but chemotherapy had to be stopped after the first cycle due to pancytopenia, aggravating thrombocytopenia, and persistent fever. The patient refused additional chemoradiotherapy. During the postoperative 15 months, liver MRI showed metastasis with increased size in the hepatic duct lymph nodes, portocaval, and paraduodenal areas, and the largest size increased from 1.8 to 3.1 cm in short diameter. The patient was alive over the 15-month follow-up period.

Pathological findings

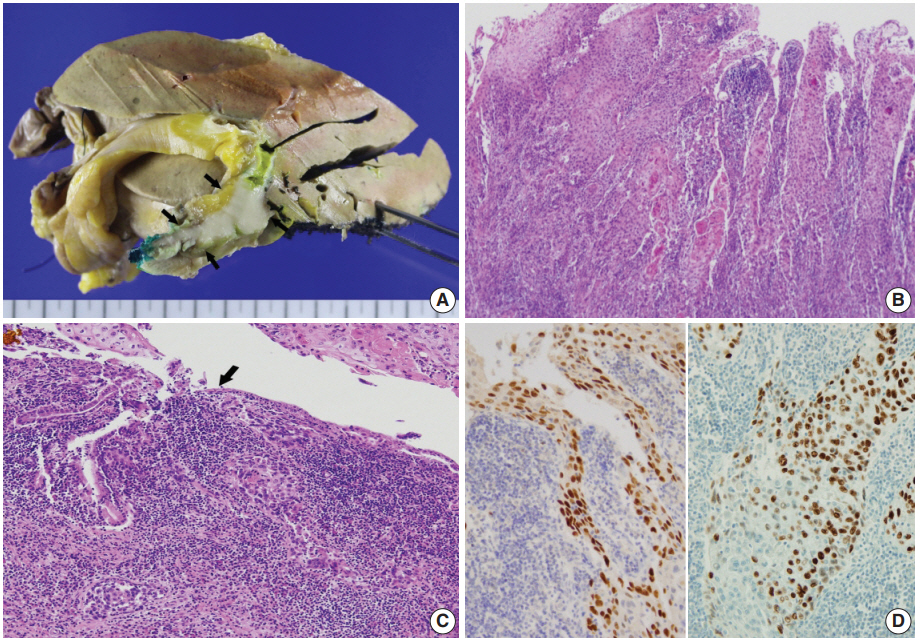

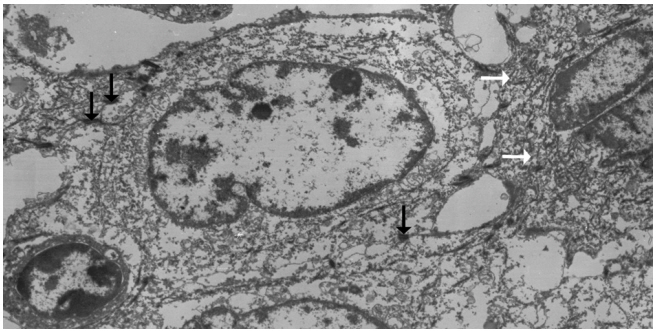

Left hemihepatectomy with S1 segmentectomy and segmental excision of the common bile duct were performed. Serial sections revealed a firm grayish-white mass measuring 2.8 cm at the proximal common hepatic duct near the hilar region (Fig. 2A). The mass did not involve the cystic duct or the right and left hepatic ducts. Microscopically, the papillary-protruded mass was composed entirely of squamous cells with eosinophilic keratin pearls (Fig. 2B). The surface of the mass was denuded and inflamed due to preoperative stent insertion. No mucin production or duct formation was detected. There were no metaplastic or biliary intraepithelial neoplastic lesions. An abrupt transition to neoplastic squamous epithelium from the cuboidal biliary epithelium was noted (Fig. 2C). Mitosis was frequently found. The tumor extended to the pericholedochal fibroconnective tissue. Lymphovascular and perineural invasion were noted. The tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 (CK5/6; 1:100, D5/16 B4, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), CK19 (prediluted, B/70, Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), p63 (prediluted, DAK-P63, Dako) (Fig. 2D), p40 (prediluted, BC28, Dako), and Ki-67 (1:100, MIB-1, Dako). However, the tumor cells were negative for CK7 (1:100, OV-TL 12/30, Dako), CK20 (1:100, KS 20.8, Dako), periodic acid Schiff, and polyclonal carcinoembryonic antigen (prediluted, polyclonal, Dako). The tumor cells were focally non-block positive for p16 (1:200, JC8, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Entirely embedded sections of tumor and bile duct revealed no adenocarcinoma component. The tumor was diagnosed as a pure SCC with moderate differentiation. Ultrastructurally, polygonal to elongated tumor cells were filled with dilated rough endoplasmic reticulums, intermediate filaments, and primary and secondary lysosomes with prominent golgi apparatus (Fig. 3). Well-formed desmosomes were found. The gallbladder was separately submitted and showed only inflammation without any stones. A 1 cm-sized abscess with periductal inflammation was noted in the background liver parenchyma. Aspiration cytology of the enlarged common hepatic arterial lymph node showed metastatic SCC (pT2aN1M0, stage IIIc according to American Joint Committee on Cancer). Human papillomavirus was not detected using the HPV 9G DNA kit (BMT, Chuncheon, Korea) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol.

(A) The gross specimen revealed a protruded mass (arrows) accounting for all layers of the hepatic duct wall. (B) Histologically, thickened papillary squamous epithelium shows moderately differentiated dyskeratotic squamous cells with keratin pearls with stromal invasion. (C) Surface epithelium shows a transition from unilayered cuboidal to squamous epithelium (arrow). (D) Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells are positive for p63 (left) and p40 (right).

Ultrastructurally, ovoid-shaped tumor cells have cytoplasmic tonofilaments (white arrows) and are connected with wellformed desmosomes (black arrows, ×2,500).

Approval was obtained from our Institutional Review Board (No. GCIRB2018-066) for this case report with a waiver of informed consent.

DISCUSSION

Histologically, the biliary mucosa is composed of a singlelayered cuboidal epithelium without squamous epithelial cells. Adenocarcinoma is the most common histologic type of biliary tract malignancies, and biliary SCC is rare. By definition, the diagnosis of adenosquamous carcinoma of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts can be made when SCC comprises more than 25% of the tumor component, but the current classification system by the World Health Organization requires that no glandular component is present for a diagnosis of biliary SCC.

The pathogenesis of this rare biliary SCC has not been elucidated to date. It is presumed that the normal columnar epithelium undergoes squamous metaplasia by continuous irritation due to an inflammatory stimulus, which then may result in carcinomatous changes through dysplasia [1]. Predisposing conditions that can lead to squamous metaplasia of the biliary epithelium and biliary SCC include hepatolithiasis, recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, and clonorchiasis [1]. Secondly, pluripotent bile duct stem cells are known to undergo malignant transformation. Other possible theories include heterotopic squamous epithelium or squamous metaplasia of preexisting adenocarcinoma [9,13]. The second and third theories might explain biliary SCC cases that lack preexisting normal squamous epithelium, like the present case. Our patient’s histology revealed pure SCC, and there was no hepatolithiasis or choledochal cysts on imaging studies. There was no underlying squamous epithelium, but there was an abrupt transition to dysplastic squamous epithelium from the biliary mucosa. On the other hand, a previous case reported by Abbas et al. [10] showed biliary SCC associated with high-grade squamous dysplasia, similar to cervical carcinogenesis. Their finding supports the metaplasia-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence theory. However, the direct causality of inflammation-metaplasia-dysplasia should be questioned. Whether gallstones predispose to cholangiocarcinoma remain unclear, and most reported cases have not been accompanied by a metaplasia-dysplasia lesion. Another possible theory may be that SCCs are derived from undifferentiated basal cells. Immunoreactivity for CK7, CK8, CK14, CK18, and/or CK5/6 suggests the origin of the cancer cells to be the basal cells of keratinized squamous epithelium. Moreover, positive staining for biliary CK19 would confirm the bile ductular ontogeny of the neoplastic cells [19].

The incidence of cholangiocarcinoma increases with age, and most reported cases occur in the fifth to seventh decades. Due to its rare incidence and strict diagnostic criteria, biliary SCC is rarely reported, and there are few reports to be retrieved for review. From the literature, we found 34 cases of biliary SCCs in the extrahepatic bile duct. Among the 34 reported cases of SCC of the extrahepatic duct, only 24 provided well-described clinicopathologic data [2-18]. Only one case associated with a choledochal cyst demonstrated predisposing precursors. A review of the cases revealed that age ranged from 24 to 86 years (mean, 62 years). The male-to-female ratio was 16:9. The site of occurrence of biliary SCC was the common hepatic duct region in four cases, hilar region in seven cases, proximal common bile duct region in two cases, mid portion in five cases, and distal common bile duct in seven cases.

A review of the previously reported cases demonstrated that the prognosis of biliary SCCs is extremely grave. Cholangiocarcinoma containing a component of SCC showed the following trends: rapid progression to advanced stage, short survival time, large tumor size, aggressive intrahepatic spreading, and frequent metastasis. Findings related to poor prognosis include elevated preoperative level carbohydrate antigen 19-9, resection margin involvement, advanced T category, and metastatic lymph node [20]. The mortality rate of biliary SCCs was up to 63.6% (14/22 cases of available data) during the follow-up period (mean, 14.8 months). Twenty out of 25 cases with available data (80%) underwent surgical resection with or without chemoradiotherapy. Among them, nine cases were combined with chemoradiotherapy. Two out of 25 cases (8%) received only conservative treatment. Ten cases (40%) received chemotherapy with or without radiation. The mean survival of patients without surgery was less than 12 months. Unlike head and neck SCCs, there is no supportive evidence for radiation therapy for unresectable biliary SCC. However, there are some reports of chemotherapy’s important palliative value for painful localized metastasis or uncontrolled bleeding [20]. These results are summarized in Table 1. Patients undergoing surgery had a better prognosis than those receiving conservative, non-surgical treatments (median survival, 32 months vs 3 months, p = .009). However, age and stage at diagnosis and associated general medical condition were also influential factors. Cases with additional chemotherapy showed a tendency toward poorer prognosis than those with surgery only, although the difference was not statistically significant (median survival, 12 months vs 32 months; p = .085). Other clinical findings, including sex, age, and site of bile duct involvement, had no impact on prognosis.

Clinicopathologic summary of reported cases of squamous cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct

Due to the extremely rare incidence of biliary SCCs, no standardized therapeutic strategies have been established. The recommended treatment for biliary SCCs is surgical resection with or without chemoradiotherapy, and the recommended chemotherapy is GEMOX (gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin) or GP (gemcitabine plus cisplatin), as in bile duct adenocarcinomas [20]. Similar to the treatment for cancers of the gastrointestinal tract such as esophageal cancers, chemotherapy with docetaxel plus cisplatin plus 5-FU therapy or S-1 plus cisplatin therapy may be helpful. With such a regimen (S-1 plus cisplatin), one patient with biliary SCC was successfully treated [16]. Combined targeted therapy, such as epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapy, has shown certain benefits in other cancer types, and its effects are being investigated.

Here, we reported a case of SCC of the hilar bile duct and reviewed previous reports regarding biliary SCCs. The poor prognosis observed in SCC patients may be attributed to its rarity, initial advanced stage, and lack of accumulated clinical data.

Notes

Author Contributions

Investigation: YHP

Supervision: DHC, HYC.

Writing—original draft: MK, NRK.

Writing—review & editing: MK, NRK.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.