New insights into classification and risk stratification of encapsulated thyroid tumors with a predominantly papillary architecture

Article information

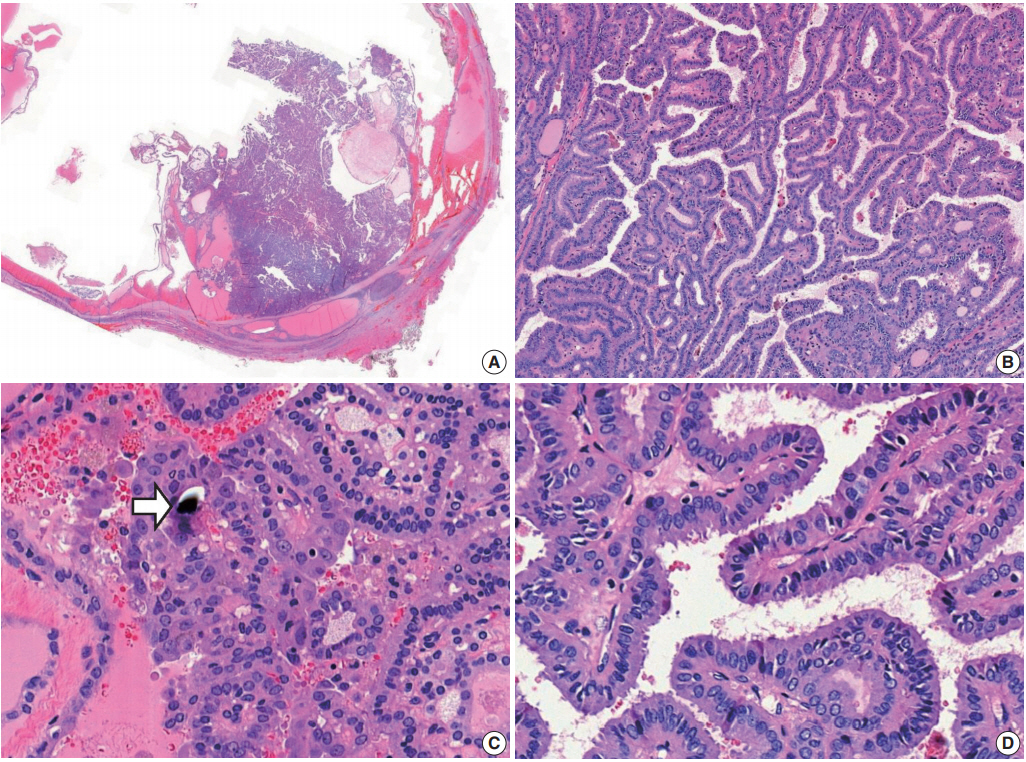

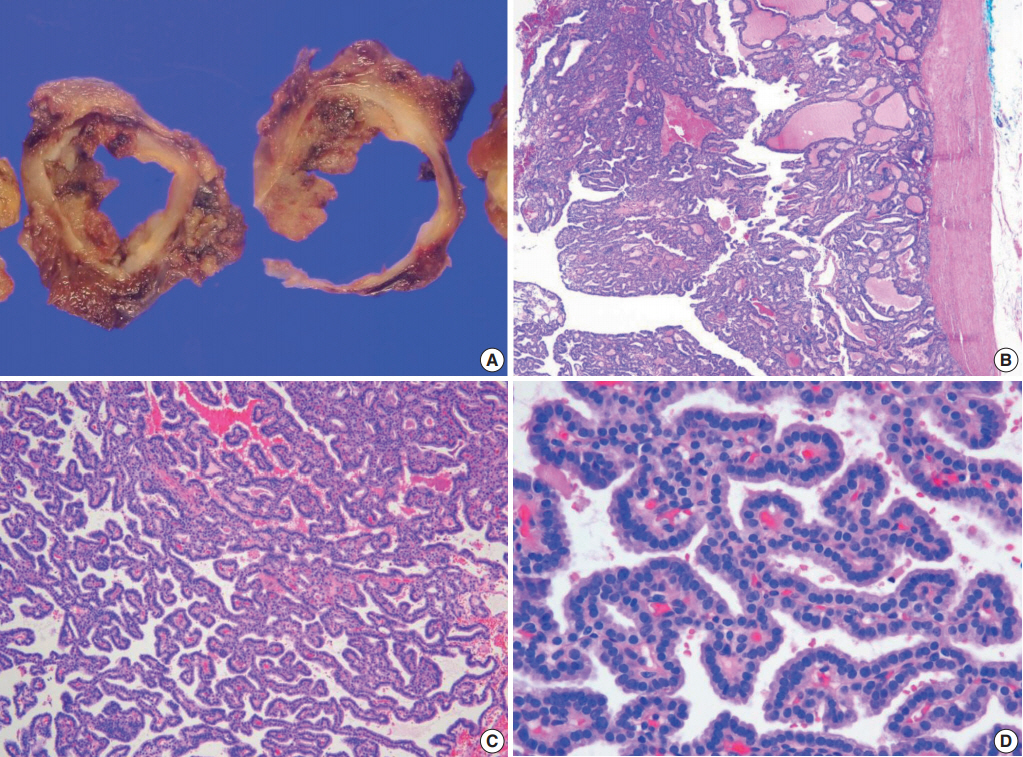

Three cases of noninvasive encapsulated papillary RAS-like (NEPRAS) thyroid tumor are reported in this issue [1]. The term “NEPRAS” was first used by Ohba et al. in 2019 [2] to designate a noninvasive thyroid tumor showing a complete fibrous capsule, a predominantly papillary architecture, and RAS mutation but with subtle nuclear features of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) (Fig. 1). The tumor was considered a borderline thyroid tumor that showed a predominantly papillary structure. The name and concept of “NEPRAS” tumors were proposed as a counterpart of noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP) having a predominantly follicular architecture. NEPRAS is different from follicular adenoma with papillary hyperplasia because of the appearance of nuclear features of PTC (Fig. 2). The distinction between NEPRAS and NIFTP is based on the presence of papillary structure in NEPRAS tumors (Table 1). NEPRAS tumors with RAS mutations or other RAS-like mutations are different from encapsulated classic PTCs in that classic PTCs typically harbor the BRAF V600E mutation. Therefore, in the diagnostic schema recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of thyroid tumors, pathologists might have variably classified these noninvasive encapsulated tumors as either benign follicular adenoma or encapsulated PTC depending on the subjective judgment of nuclear features.

Noninvasive encapsulated papillary RAS-like thyroid tumor. (A) The tumor has a thick fibrous capsule and shows cystic change. (B) The solid area is predominantly composed of papillary architecture lined by cuboidal to columnar follicular cells. (C) Psammoma bodies are occasionally seen (arrow). (D) Tumor cells show nuclear enlargement, overlapping, and elongation, with slightly irregular nuclear membranes and dark chromatin, and have no nuclear pseudoinclusions. Molecular analysis revealed KRAS G12V mutation.

Follicular adenoma with papillary hyperplasia. The tumor is cystic and has a thick complete capsule upon gross (A) and microscopic examination (B). (C) The tumor is composed of a predominantly papillary structure. (D) Tumor cells show basally located, small, and dark nuclei with round contours.

The 2017 WHO classification newly adopted a borderline tumor of the thyroid [3]. Encapsulated follicular-patterned thyroid tumors with borderline behavior include follicular tumor of uncertain malignant potential (FT-UMP), well-differentiated tumor of uncertain malignant potential (WDT-UMP), and NIFTP [3]. FT-UMP has round nuclei that lack PTC-type nuclear features, whereas WDT-UMP and NIFTP share the nuclear features of PTC, including a nuclear score of 2 or 3 on a three-point scoring scale [3]. Although encapsulated follicularpatterned lesions are well defined by the WHO classification, there is a lack of consensus on encapsulated papillary-patterned thyroid tumors that demonstrate subtle nuclear changes. Many diagnostically controversial cases exhibit subtle nuclear features, such as a nuclear score of 2, and therefore pose challenges for accurate diagnosis.

Pathologic diagnosis of a thyroid tumor is fundamentally dependent on pathologists’ knowledge and experience in interpreting microscopic findings [4-8]. Due to variable application of loose or strict criteria in assessing the nuclear features of PTC and its invasion of the tumor capsule and vessels, there is discrepancy in diagnosis of encapsulated/well-circumscribed thyroid tumors among pathologists [6-9]. Noninvasive encapsulated papillary-patterned thyroid tumor is diagnosed as encapsulated classic PTC if nuclear features of the tumor are interpreted as nuclear score of 3. However, diagnostic challenges may arise in cases with subtle nuclear changes. In Western practice, equivocal nuclear changes are more easily interpreted as PTC-type nuclear features, whereas most Asian pathologists agree that such nuclear features are insufficient for diagnosis of PTC [10]. As a result, the same tumor can be diagnosed as a follicular adenoma by certain pathologists who apply more stringent criteria for diagnosis of PTC.

RAS-mutated thyroid tumors demonstrate different histology and biological behavior than tumors with BRAF V600E mutation [11]. RAS or other RAS-like mutations are frequently found in follicular adenoma, NIFTP, and follicular carcinoma with a similarity in the possible spectrum of mutations [12-14]. In PTCs, two molecular subtypes, BRAF V600E-like and RAS-like types, were proposed by the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project [11]. Follicular-patterned PTCs typically carry RAS-like mutations, including RAS mutations, whereas PTCs with papillary architecture have BRAF V600E or other BRAF-like mutations. However, this rule does not apply in all cases. RAS-like mutations can be found in PTCs with papillary architecture. In the TCGA dataset [11], of 250 classic PTCs with molecular classification data, 43 (17.2%) had an RAS-like molecular signature, while 16 (6.3%) had RAS mutations. Noninvasive encapsulated papillary-patterned tumor can also demonstrate PTC-like nuclear features and RAS mutations. The tumor was previously classified either as encapsulated classic PTC if it had a nuclear score of 2–3 or as follicular adenoma with papillary hyperplasia if it had a nuclear score of 0 or 1 according to the WHO classification [3]. However, the new diagnostic term “NEPRAS” can reclassify a subset of noninvasive encapsulated papillary-patterned tumors as borderline tumors [2].

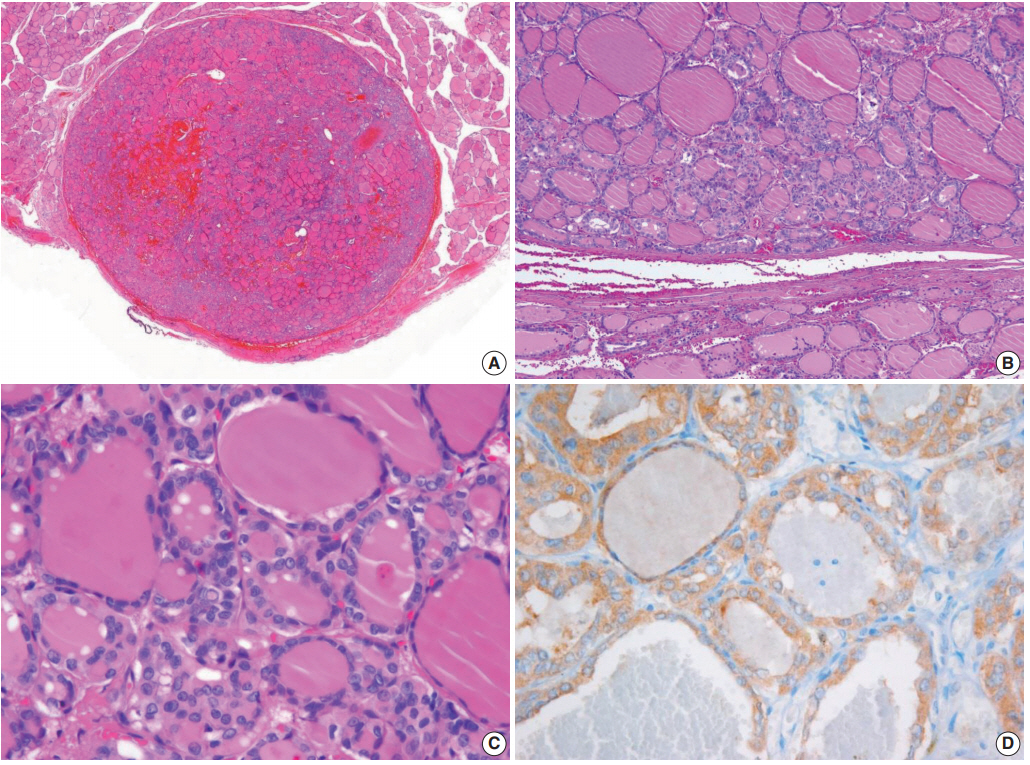

NEPRASs share common characteristics of NIFTP as a noninvasive encapsulated tumor, having RAS-like mutations, and demonstrating a PTC-type nuclear score of 2. However, NEPRAS lesions are papillary-patterned tumors and can have psammoma bodies (Fig. 1). Because the presence of true papillae and psammoma bodies suggest the probability of classic PTC, these findings are major exclusion criteria for the diagnosis of NIFTP. A nuclear score of 3 and the well-developed nuclear features of PTC are not exclusion criteria for NIFTP, but they indicate a higher probability of classic PTC and should serve as an indicator for a more thorough examination of the tumor, including more grossing and immunostaining or molecular testing for BRAF V600E (Fig. 3) [15-18]. As encapsulated papillary-patterned tumors with nuclear scores of 3 are frequently positive for the BRAF V600E mutation and therefore confidently diagnosed as PTC, a nuclear score of 3 is an exclusion criterion for diagnosis of NEPRAS. While NEPRAS remains a morphologic diagnosis like NIFTP, detection of RAS-like low-risk mutations (RAS, BRAF K601E, EIF1AX, PPARGfusion, THADA fusion, and so forth) further substantiates the diagnosis when molecular results are available. BRAF-like mutations (BRAF V600E, ALK, RET/PTC, NTRK fusions, etc.) and high-risk mutations (TERT promoter, TP53, PIK3CA, CTNNB1, etc.) are essentially exclusionary criteria for diagnosis of NEPRAS and NIFTP lesions. In our case series (Table 2), one NEPRAS tumor had a KRAS mutation. In addition, the NRAS mutation was found in one NEPRAS tumor showing minimal capsular invasion. Another case had no RAS mutations.

Noninvasive encapsulated classic papillary thyroid carcinoma with predominant follicular growth and BRAF V600E. This tumor was initially misdiagnosed as noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP). (A) The tumor is completely surrounded by a thin fibrotic capsule. (B) The encapsulated tumor is composed of follicular architecture. (C) The tumor cells have florid nuclear features of papillary carcinoma. Nuclear pseudoinclusions and grooves are frequently seen. (D) Immunostaining for BRAF V600E (VE1) is positive.

Cases of noninvasive encapsulated papillary RAS-like thyroid tumor and its malignant counterpart with invasion

Most encapsulated thyroid tumors without invasion are very indolent and behave like follicular adenoma despite their growth patterns. The management strategy for patients with NEPRAS tumors is similar to those with NIFTP lesions. Thyroid lobectomy is a sufficient treatment for NEPRAS and NIFTP tumors. No further surgery, completion thyroidectomy, or radioactive iodine treatment is required after surgical resection of the primary tumor. Thus, reclassification of a subset of encapsulated classic PTCs into borderline tumors would ultimately lead to more conservative treatment standard and improved quality of life for patients with these tumors.

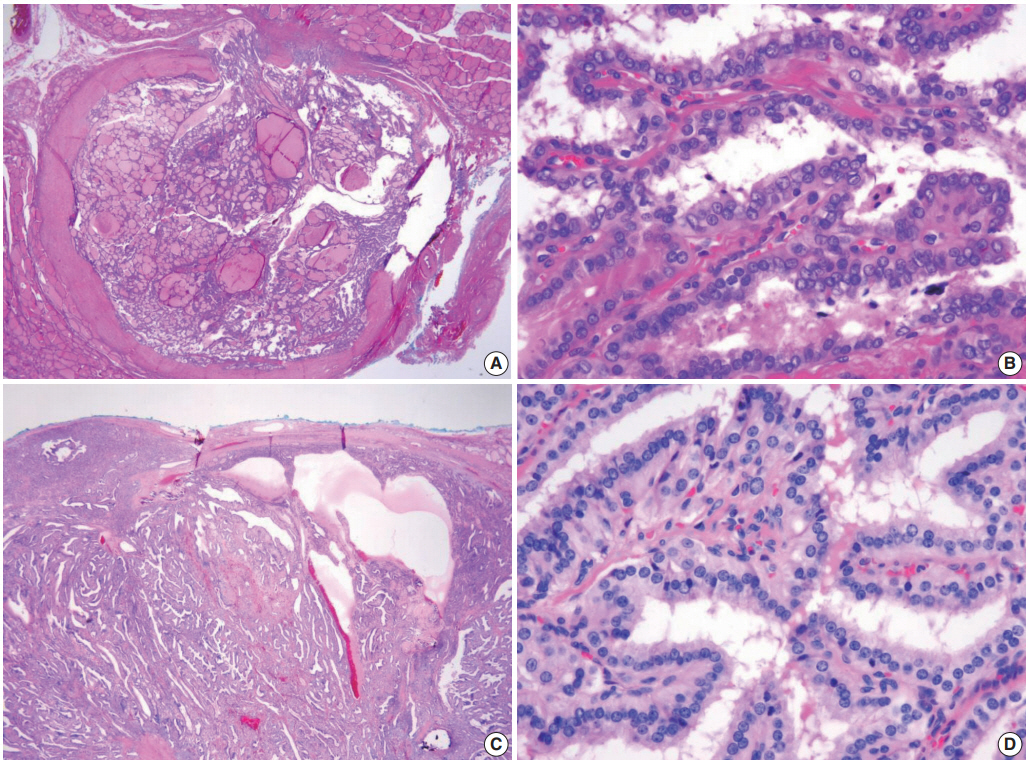

NEPRAS tumors can progress to invasive cancer just as NIFTP has the potential to progress to an invasive encapsulated follicular variant of PTC (Fig. 4). When NIFTP and NEPRAS tumors develop capsular and/or vascular invasion, they are truly malignant and mostly labelled as PTCs based on the PTC-type nuclear features (Table 1). However, the same cases may be diagnosed as follicular carcinoma if the nuclear features are interpreted as a nuclear score of 1. Fortunately, these tumors are lowrisk cancers despite their name and do not require additional treatment after surgical resection if the tumor is only minimally invasive without angioinvasion. Table 2 summarizes the reported cases in the literature, including our cases.

Two cases of the invasive form of noninvasive encapsulated papillary RAS-like thyroid tumor. (A, B) A tumor with NRAS Q61R. (C, D) The other case without BRAF V600E or RAS mutations. Both tumors show capsular invasion (A, C). A high-power view of the tumors reveals enlarged round-to-ovoid, overlapping nuclei with few nuclear grooves and less chromatin clearing than seen in classic papillary carcinoma.

Although long-term follow-up results of patients with NEPRAS are not available, it is reasonable to expect an excellent outcome after surgical resection of the tumor. Even when late recurrences do occur, the disease can be successfully treated. While reclassification has important impacts in clinical practice, implementation of new diagnostic criteria and terminologies may provoke resistance in pathologists and clinicians at variable levels. However, these efforts by pathologists will contribute to reducing the incidence rates of overdiagnosis and overtreatment of thyroid cancer.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (IRB No. KC20ZASI0282), Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB No. B-2004-611-103), and Ajou University Hospital (IRB No. AJIRB-BMREXP-20-074) with a waiver of informed consent.

Notes

Author contributions

Conceptualization: CKJ, KK.

Data curation: CKJ, SYP, JHK, KK.

Formal analysis: CKJ.

Funding acquisition: CKJ.

Investigation: CKJ.

Methodology: CKJ, SYP, JHK, KK.

Project administration: CKJ.

Resources: CKJ.

Supervision: CKJ.

Validation: CKJ, SYP, JHK, KK.

Visualization: CKJ, KK.

Writing—original draft: CKJ.

Writing—review & editing: CKJ, SYP, JHK, KK.

Conflicts of Interest

C.K.J. and S.Y.P. are the editors-in-chief of Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine. J.H.K. and K.K. are editorial-board members of the journal.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant (2017R1D1A1B03029597) from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT.