Standardization of the pathologic diagnosis of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms

Article information

Abstract

Although the understanding of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (AMNs) and their relationship with disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease have advanced, the diagnosis, classification, and treatment of AMNs are still confusing for pathologists and clinicians. The Gastrointestinal Pathology Study Group of the Korean Society of Pathologists (GPSG-KSP) proposed a multicenter study and held a workshop for the “Standardization of the Pathologic Diagnosis of the Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm” to overcome the controversy and potential conflicts. The present article is focused on the diagnostic criteria, terminologies, tumor grading, pathologic staging, biologic behavior, treatment, and prognosis of AMNs and disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease. In addition, GPSG-KSP proposes a checklist of standard data elements of appendiceal epithelial neoplasms to standardize pathologic diagnosis. We hope the present article will provide pathologists with updated knowledge on how to handle and diagnose AMNs and disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease.

Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (AMNs) are rare appendiceal epithelial tumors, characterized by mucinous epithelial proliferation with extracellular mucin and a common cause of disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease, pseudomyxoma peritonei [1-3]. The accurate diagnosis of AMNs is clinically important because management may include a long-term follow-up to radical innovative therapy, such as cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS-HIPEC) and systemic chemotherapy [1-5]. However, the definition and classification of AMNs have been inconsistent, which causes potential confusion when diagnosing and managing patients [5-11]. Recently, an international working group, Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI), reached a modified Delphi consensus on classifications and diagnostic terminologies [12]. Although this was a global effort, the terminology of AMNs is still contentious. To establish a tumor staging system, the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC 8th) Cancer Staging Manual applied pT staging to lowgrade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (LAMNs) for the differentiation of high-grade diseases [13,14]. However, the biologic behaviors of AMNs and disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease are still controversial among the pathologists who perform diagnoses without adequate guidelines.

The Gastrointestinal Pathology Study Group of the Korean Society of Pathologists (GPSG-KSP) has contributed to the establishment of standard pathologic guidelines for gastrointestinal neoplasms [15-21]. However, there are no well-established or consensus guidelines for diagnosing and evaluating AMNs, leading to confusion and potential conflict in daily practice and medical insurance compensation. There is a need to assess cancer registration because of changes in the newly published 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification (WHO 5th) of Digestive System Tumors and the AJCC 8th Cancer Staging Manual. AMNs are uncommon appendiceal epithelial neoplasm, and there are many limitations in a single institution study. The GPSGKSP proposed a multicenter study to overcome the limitations and held a workshop entitled “Standardization of the Pathologic Diagnosis of the Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm.” The GPSGKSP recruited institutions and pathologists and collected cases diagnosed as AMNs and related diseases in each institution from 2011 to 2015. Expert pathologists of the GPSG-KSP selected typical cases with AMNs and disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease according to the PSOGI consensus guidelines [12], the College of American Pathologists (CAP) protocol [22], the AJCC 8th Cancer Staging Manual [13], and the WHO 5th Digestive System Tumors [1]. Expert pathologists reached the consensus in the collected cases through a live microscopic examination using a 12-head microscope if conflicting cases were presented. One hundred and twenty-one members of the KSP participated in the workshop. Virtual slides provided a total of 23 cases during the workshop. Before the workshop, we asked several questions about the basic information of the participants and diagnostic terminologies and stagings of the AMNs (Supplementary Data S1). After a lecture on updates, we surveyed several issues about the diagnostic criteria, biologic behavior codes, and tumor gradings of the AMNs and disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease (Supplementary Data S2). We collected their responses and discussed differing opinions with members of the GPSG-KSP. In addition, we propose an essential checklist of standard data elements of the appendiceal epithelial neoplasms for the standardization of pathologic diagnosis of AMNs and disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease.

APPENDICEAL MUCINOUS NEOPLASMS

Definition and characteristics of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms

Appendiceal epithelial neoplasms, over 70% of the mucinproducing type, account for most primary appendiceal tumors [1-3]. The classification of appendiceal epithelial tumors of the WHO 5th Digestive System Tumors is listed in Table 1. The WHO 5th Digestive System Tumors defined the AMN as a mucinous epithelial proliferation with extracellular mucin and pushing invasion pattern or pushing tumor margins [1]. Most AMNs develop in middle-aged or elderly patients and present with non-specific symptoms or signs, such as acute abdominal pain [1-5,12]. AMNs can exhibit variable clinical behaviors, ranging from a relatively slow-growing and low-grade tumor, but with considerable risk of recurrence, to a high-grade and aggressive neoplasm that produces eventual peritoneal metastasis [1-7]. AMNs can be divided into LAMN and high-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (HAMN) by cytological grading. The classification, grading, biologic behavior codes, diagnostic criteria, and microscopic features are listed in Table 2.

Pushing invasion in appendiceal mucinous neoplasms

Pushing invasion is defined as a tongue-like protrusion, diverticulum- like growing, or broad-front spread of the epithelium into the appendiceal wall [1,3,12]. Pushing invasion can cause the attenuation of lamina propria and muscularis mucosae, and this is not associated with the destructive invasion or desmoplastic infiltration, characteristics of invasive carcinoma [1,3,12,23]. Moreover, pushing invasion through the appendiceal wall presents extra-appendiceal mucin accumulation, leading to diagnostic difficulty or misdiagnosis. Extracellular mucin can lead to the dissection of the wall and rupture with the potential for intraperitoneal dissemination [24,25].

LOW-GRADE APPENDICEAL MUCINOUS NEOPLASM

Definition and histologic findings of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm

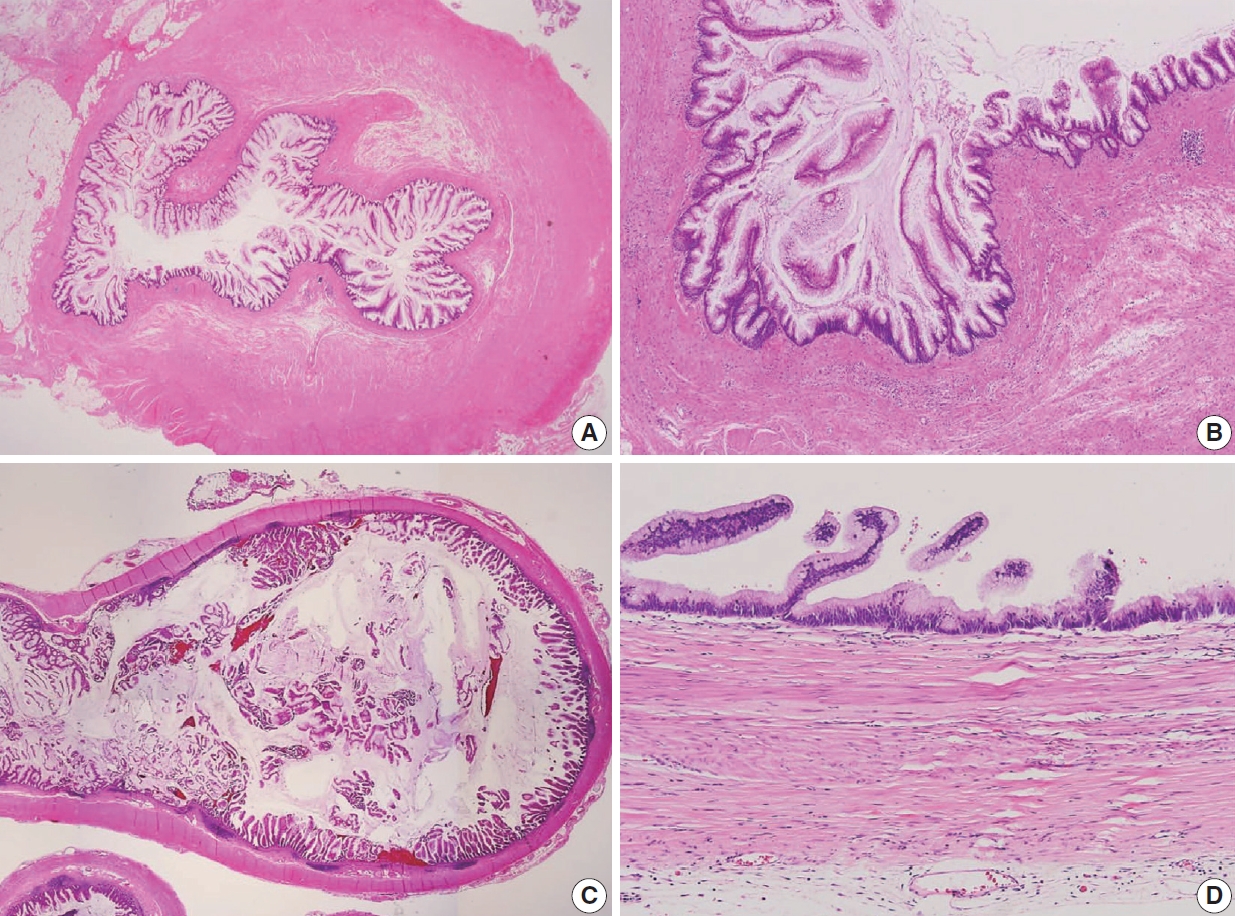

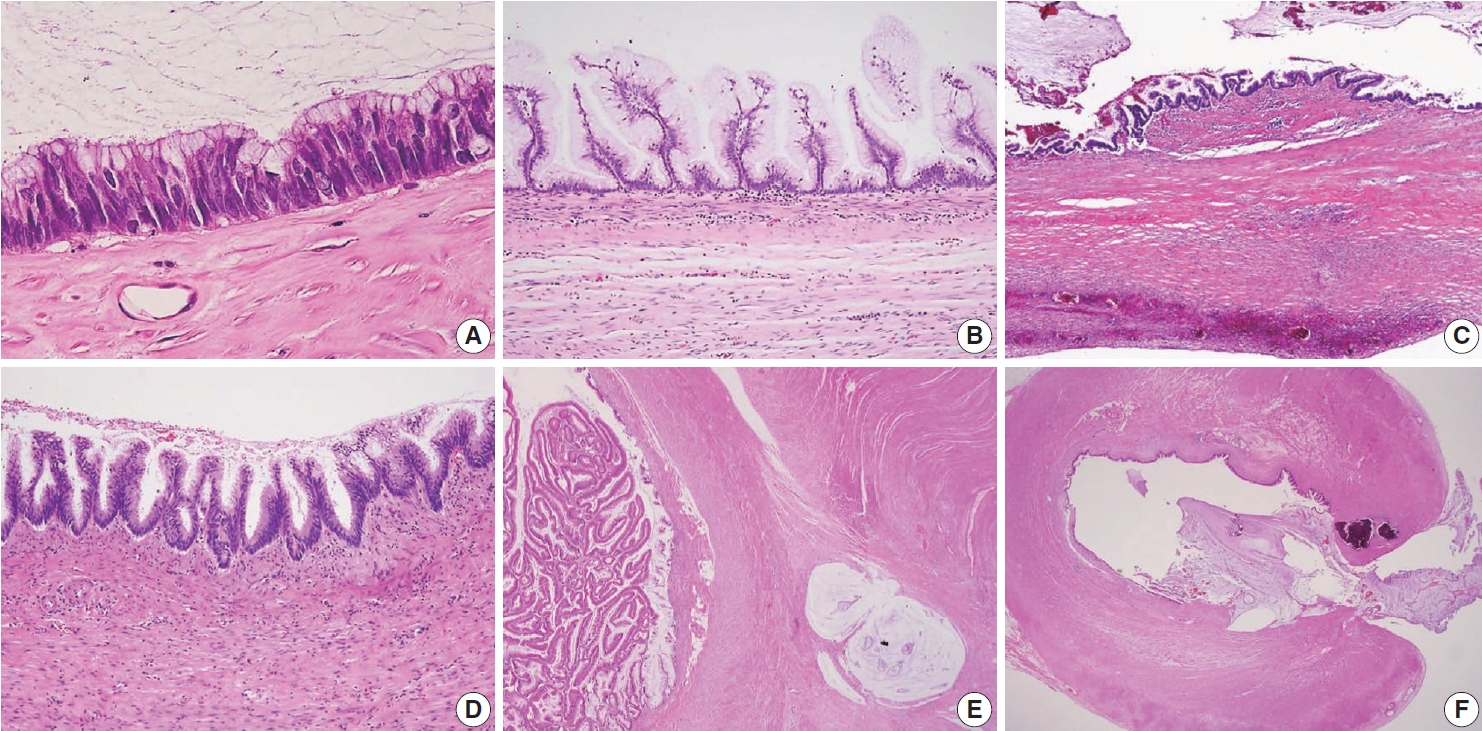

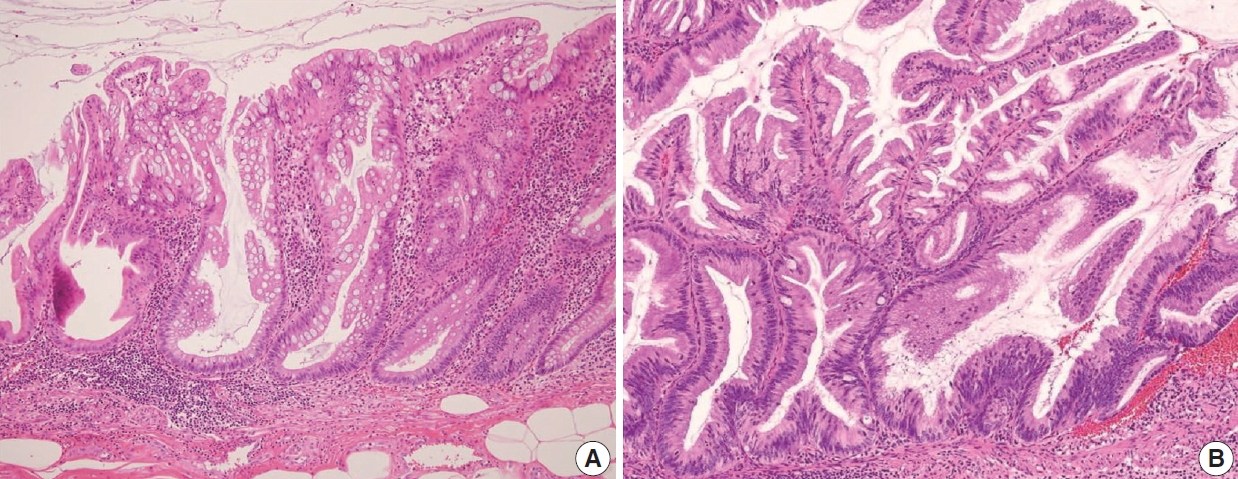

The AJCC 8th Cancer Staging Manual defined a LAMN as a mucinous neoplasm with low-grade cytology associated with the obliteration of the muscularis mucosae without overt features of the invasion [13]. The lamina propria is frequently effaced, and mucosal lymphoid tissues are decreased or absent. Mucinous cystadenoma and mucocele were histologically used as synonyms for LAMN but are no longer recommended in pathologic reports due to their ambiguous and misleading nature. The essential histologic finding of LAMN is low-grade cytology with pushing invasion; however, there is no destructive invasion in the appendiceal wall. Fig. 1 demonstrates the microscopic features of LAMNs, displaying pushing invasion and broad-front spreading by a mucin-rich epithelium. Notably, when regarding whether pushing invasion is necessary for the diagnosis of LAMN, most of the survey responders diagnosed Fig. 1A, B as LAMN. In typical LAMNs, there is a loss of the normal mucosal architectures, at least focally, such as obliteration of the lamina propria and muscularis mucosa, fibrosis of the submucosa, and atrophy of the lymphoid follicles. Although the epithelium may show a papillary, villous, undulating, or flat architecture, lining epithelial cells are generally arranged in a monolayer (Fig. 1C, D). The microscopic features essential for LAMN proposed by the PSOGI panel are illustrated in Fig. 2. It is not surprising that LAMN with intact muscularis mucosae may develop disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease. For this reason, there is hesitancy in diagnosing a lesion with intact muscularis mucosae as adenoma because adenomas should be limited to benign lesions that have no potential for peritoneal dissemination. Patients with LAMN often present symptoms like acute appendicitis. Typical LAMNs usually have thin fibrotic walls and abundant intraluminal mucin, and less commonly, calcification of the wall. Grossly apparent rupture with mucin extrusion is generally manifested in patients with disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease.

Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN). (A) A LAMN demonstrates a “pushing invasion” or tongue-like protrusion into the appendiceal wall. (B) A LAMN reveals a pushing growth by the mucinous epithelium into the appendiceal wall, which should not be considered as infiltrative invasion. (C) A LAMN shows a “pushing border” or broad-front border by the epithelium. (D) A LAMN reveals a flat or papillary epithelium associated with the loss of the lamina propria, obliteration of muscularis mucosae, and atrophy of submucosa and muscularis propria.

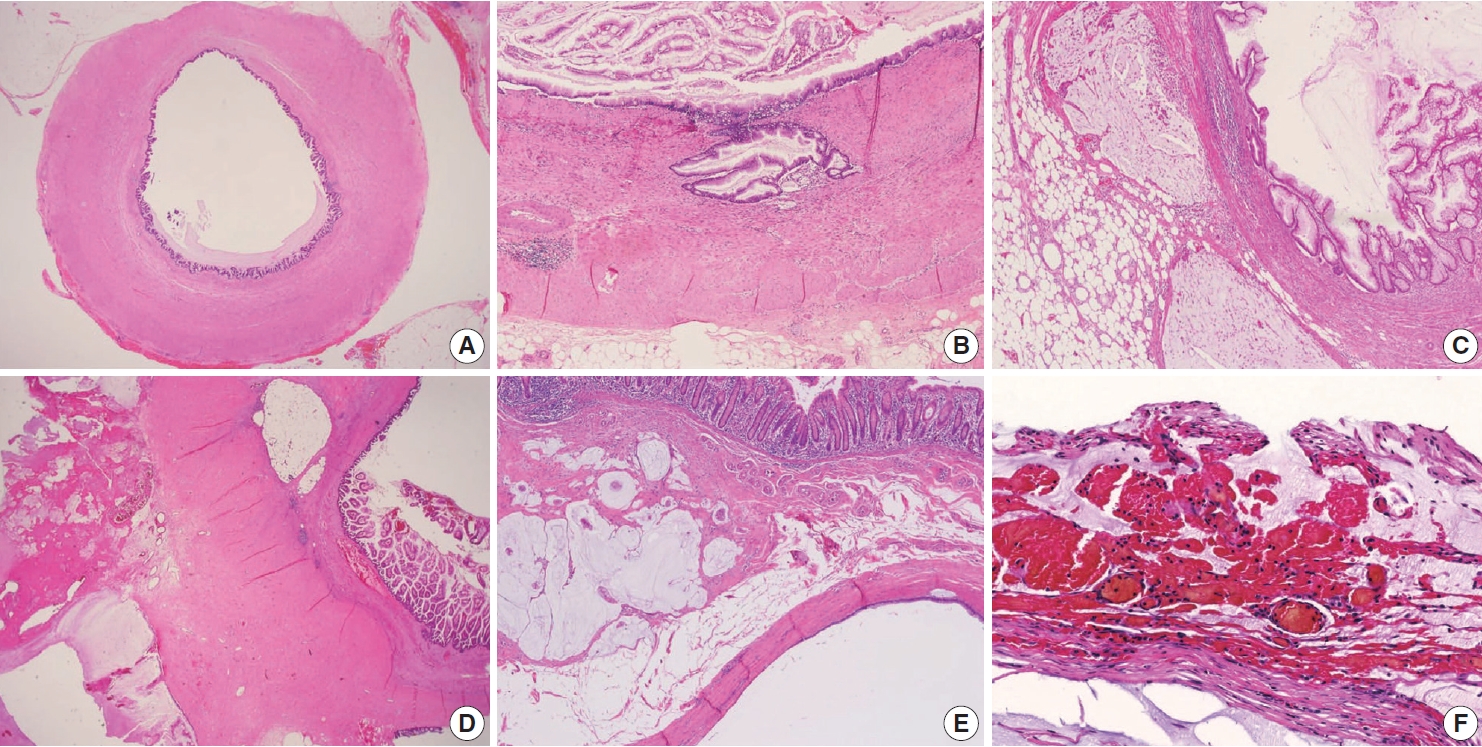

Various microscopic features of a low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm. (A) Low-grade cytologic features with pencil-like nuclei maintaining the nuclear polarity. (B) The neoplastic mucinous epithelium may have a villous architecture with loss of lamina propria and muscularis mucosae. (C) The appendiceal wall exhibits extensive fibrosis. (D) The neoplastic epithelium displays an undulating or short wave-like architecture. (E) The appendiceal wall is dissected by mucin. (F) Rupture of the wall by mucin and/or cells outside the appendix.

Mimickers of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm

Because LAMNs show benign-looking cytology, they can mimic several benign lesions associated with mucinous epithelial proliferation. The appendiceal diverticulum is perhaps the most common mimicker of LAMN due to their pushing growing pattern, specifically when related to abundant mucin exposed to the serosal surface. A preserved lamina propria is an indication of the diagnosis of a diverticulum. Careful examination of the entire appendix at lower magnification often leads to identifying a diverticulum. Sometimes, Schwann cell hyperplasia expands the lamina propria, possibly because of the obliteration effects [26,27]. If a histologic examination of the entire appendix fails to reveal a lining epithelium, the possibility of a retention cyst may be considered. Appendiceal retention cysts are rare and mostly small-sized; thus, lesions more than 2 cm in diameter are much more likely to be LAMNs. Appendiceal endometriosis with intestinal metaplasia is uncommon and can resemble a LAMN. The epithelial component acquires an intestinal phenotype characterized by columnar mucin-secreting cells, sometimes with goblet cells. Recognition of the endometrial stroma surrounding the glands and CD10 immunohistochemical stain will lead to a diagnosis. Mucosal hyperplasia can be seen in acute appendicitis. Mucosal hyperplasia tends to be more pronounced toward the luminal side and is frequently observed in areas of intense inflammation. Occasionally, reactive cellular atypia in the acute suppurative appendicitis may approximate the neoplastic atypia in LAMN. Fig. 3 reveals various mimickers of LAMN.

Mimickers of appendiceal mucinous neoplasm. (A) Acute suppurative appendicitis. (B) An appendiceal diverticulum presents pushing growth by abundant mucin and acute suppurative inflammation. Note that a lower magnification often leads to the identification of the diverticulum. (C) Retention cyst without a lining epithelium. (D) Appendiceal endometriosis.

HIGH-GRADE APPENDICEAL MUCINOUS NEOPLASM

Definition and histologic of HAMN

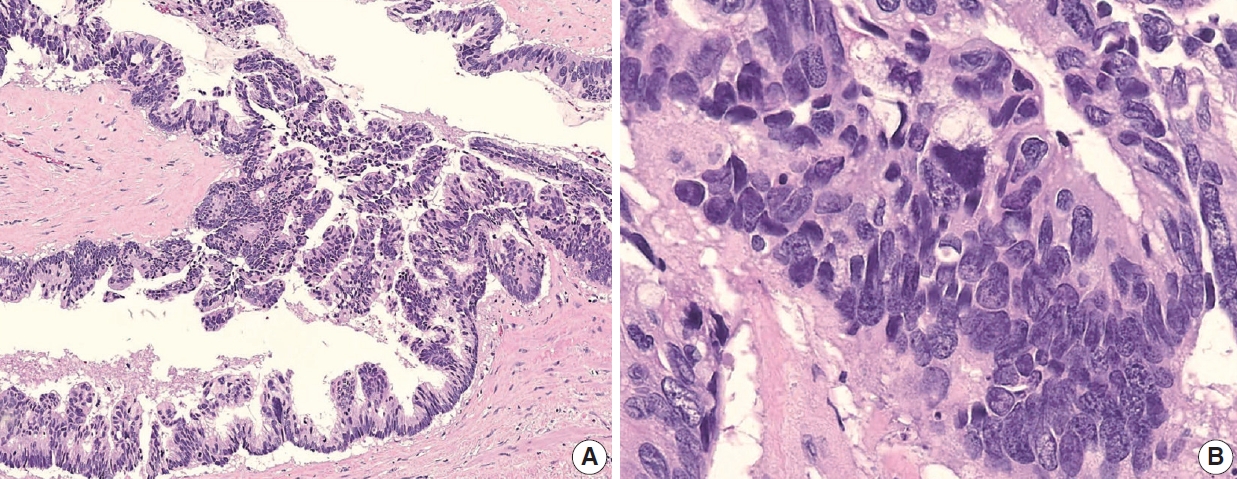

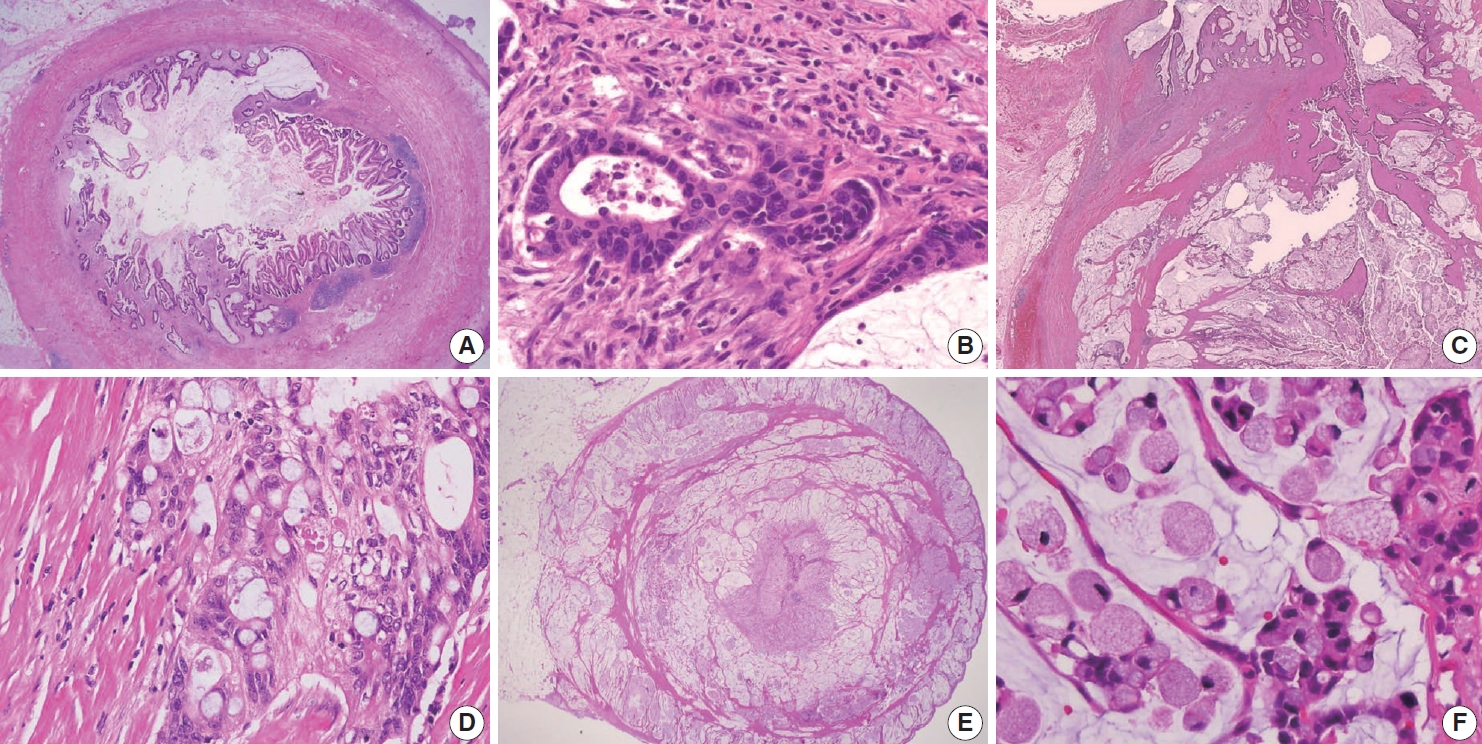

HAMN was proposed for the lesion with similar architectures of LAMN having high-grade cytologic features but no infiltrative invasion [13]. Fig. 4 demonstrates the histologic findings of HAMN. The microscopic findings include cribriform, loss of nuclear polarity, high-grade cytology (i.e., enlarged, hyperchromatic, pleomorphic nuclei, and atypical mitotic figures), frequent single-cell necrosis and may present sloughing of necrotic cells into the lumen [23]. HAMNs are suggested to reveal an intermediate risk between LAMNs and mucinous adenocarcinomas.

High-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (HAMN). (A) A HAMN shows the same low-power architectural features as low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm without infiltrative invasion. (B) A HAMN is characterized by high-grade cytology, including enlarged and vesicular nuclei with full-thickness stratification, loss of nuclear polarity, prominent nucleoli, and sometimes mitotic figures.

Biologic behavior code of HAMN

According to the WHO 5th Digestive System Tumors, the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O3) behavior codes for LAMN and HAMN were proposed as 8480/1 and 8480/2, respectively (Table 2). The response of the ICD-O3 of the HAMN was varied at the workshop because the questionnaire for the suspected ICD-O3 behavior code of the HAMN was conducted before the publication of the WHO 5th Digestive System Tumors. However, there was a consensus that the behavior code should be 8480/2 to avoid confusion in the following GPSG meeting. Misdraji et al. [7] reported that HAMNs show more aggressive clinical behavior than LAMNs, but the prognosis is still not unveiled because HAMNs are extremely rare. Therefore, nothing of the HAMNs prognosis is known. Yantiss et al. [11] reported that HAMN was more likely to be associated with aggressive clinical course and extra-appendiceal mucin spreading than LAMN. Carr et al. [23] proposed that HAMN should include lesions with high-grade cytologic atypia that is seen only focally, provided it is unequivocal; however, there has been no accepted consensus on the quantification of focal lesions yet. We surveyed the “focal” concept at the workshop, and the responses are shown in Supplementary Data S2.

SERRATED LESIONS

Classification of appendiceal serrated lesions

The WHO 5th Digestive System Tumors defined an appendiceal serrated lesion as a mucinous epithelial lesion characterized by a serrated (sawtooth or stellate) architecture of the luminal crypt [1]. Serrated lesions are classified as a hyperplastic polyp, sessile serrated lesion without dysplasia, and serrated lesion with dysplasia or serrated dysplasia [1,14]. Polyps that lack a luminal crypt of serrated architecture and dysplasia are classified as hyperplastic polyps. Sessile serrated lesions are commonly deficient in cytological dysplasia. They often involve mucosa in a diffuse circumferential fashion. Serrated dysplasia refers to conventional adenoma-like dysplasia, traditional serrated adenoma-like dysplasia, and mixed morphological patterns of dysplasia [14]. LAMNs are heterogeneous, with typical LAMN in some areas and serrated lesions in others, raising the possibility that some LAMNs could arise from serrated lesions.

Pathologic findings and pathogenesis of appendiceal serrated

Occasionally, LAMNs simulate a serrated lesion and are challenging to diagnose, particularly if the muscularis mucosae is intact. By the diagnostic criteria of the PSOGI classification, a serrated lesion should be confined to the lesion with intact muscularis mucosae, no mucin in the wall or outside, and no expansile growth pattern or pushing invasion [12]. Although appendiceal serrated lesions have similar microscopic features to their colorectal counterparts, they commonly harbor KRAS mutations but lack BRAF mutations, indicating that the serrated pathway in the appendix is likely to be different from those of the colorectum [14,23,28]. However, serrated lesions remain incompletely studied and are not fully understood. The serrated lesions of the appendix are demonstrated in Fig. 5.

Appendiceal serrated lesions. (A) A sessile serrated lesion without dysplasia is a common microscopic finding to the colorectum counterpart, displaying deep crypt serration and dilated bases. Note that the muscularis mucosae are intact. (B) Serrated dysplasia, low grade presents adenoma-like dysplasia in the crypt base.

STAGING OF APPENDICEAL MUCINOUS NEOPLASMS

AJCC 8th TNM staging

The AJCC 7th Cancer Staging Manual was not clear on applying the staging criteria of AMNs [29]. However, the AJCC 8th Cancer Staging Manual showed significant changes to the staging criteria of AMNs, particularly for LAMN [13]. In addition, the role of acellular mucin or a mucinous epithelium outside of the appendix is also addressed and included in the staging [1,13]. A summary of the AJCC pT classification of LAMN and prognostic significance from the AJCC 8th Cancer Staging Manual is listed in Table 3. In non-mucinous appendiceal tumors, the pTis category includes high-grade dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, and intramucosal carcinoma [13]. Notably, LAMNs confined to the appendiceal wall are classified as pTis. The staging of pTis reflects the excellent outcome when limited to the appendiceal wall [13]. In most LAMNs, there is no well-preserved mucosal architecture; hence, assessing the involvement of the mucosa and submucosa is impossible, resulting in the inability to apply pT1 designation to the LAMNs. In addition, studies evaluating the outcomes in LAMN have determined that pushing invasion into the appendiceal wall is not associated with tumor recurrence [7,11,30]. Thus, pT2 designation does not apply to LAMN [13].

Staging of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm

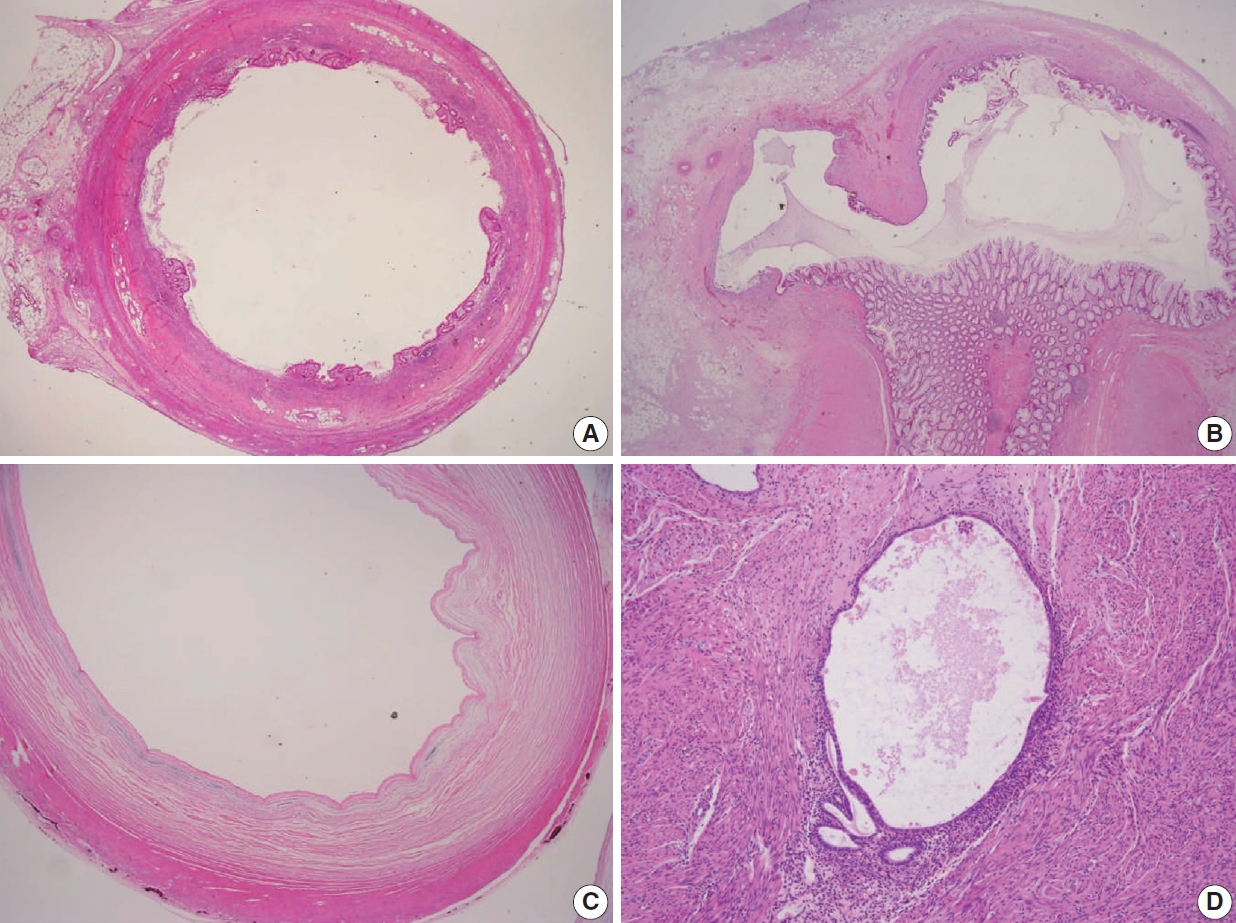

Various pT stagings of LAMN were presented in the workshop and are illustrated in Fig. 6. In a questionnaire for suspected pTis or other stages, many pathologists were unaware of the new concept of pTis(LAMN). Because mucinous tumors can frequently extend into the muscularis propria by pushing invasion in LAMN, mucin extending into the muscularis propria should be classified as pTis(LAMN) as long as it does not extend into the mesoappendix or serosa (Fig. 6A, B). LAMNs showing either acellular mucin or mucinous epithelium involvement to subserosa or mesoappendix are classified as pT3 (Fig. 6C). Perforation of the appendix by LAMN is associated with a high risk of peritoneal dissemination. Given the risk of disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease, pT4 includes assessing both acellular mucin and the mucinous epithelium and is designated as T4a (penetration of the serosa) (Fig. 6D) and T4b (directly invades adjacent organs or structures) (Fig. 6E). Notably, pT4a does not include luminal or mural spreading into the cecum. Most cases of LAMNs are associated with luminal mucin. This mucin can frequently contaminate the serosa during the gross examination, histologic processing, and even operation. These cases should not be diagnosed as pT4a. Indeed, mucinous deposits on the appendiceal serosa are associated with a granulation tissue-like response and neo-vascularization; numerous small capillaries containing red blood cells are seen coursing through the mucin (Fig. 6F). When the peritoneal dissemination is limited to acellular mucin only, it is classified as M1a. Other metastatic categories are M1b, which refers to metastases confined to the peritoneum only, and M1c which refers to metastases outside the peritoneum, such as pleuropulmonary metastasis.

Pathologic staging of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (LAMNs). (A) A LAMN confined to the appendiceal wall is designated as pTis(LAMN). (B) Acellular mucin or mucinous epithelium may frequently extend into the muscularis propria; however, the pT stage is defined as pTis. Note that pT1 and pT2 do not apply to LAMN. (C) A LAMN extends to the subserosa or mesoappendix and is classified as pT3. (D) Acellular mucin or mucinous epithelium penetrating the serosal surface is classified as pT4a. (E) The tumor directly invades into the adjacent intestinal segment by way of the serosa, e.g., invasion of the ileum (pT4b). (F) Acellular mucin on the serosal surface with inflammatory reaction and neovascularization (pT4a).

Staging of HAMN

According to the Union for International Cancer Control staging system, LAMN and HAMN are considered as pTis, if confined to the appendiceal wall [1]. However, the AJCC 8th Cancer Staging Manual stated that the HAMN should be staged using the same staging system as invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma [13]. These two different opinions may bring confusion in daily practice. Valasek and Pai [3] proposed that HAMN with pushing invasion into the muscularis propria would be classified as pT2 using the same staging system for invasive adenocarcinoma. However, since there are very few cases of HAMN, the actual application of the staging for HAMNs will be determined after the results of large-scale survival analysis. We surveyed the expected pT stages of the HAMNs at the workshop, and the responses are shown in Supplementary Data S2.

APPENDICEAL MUCINOUS ADENOCARCINOMA

Definition and histologic findings of appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinoma

Appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinoma is defined as mucinous neoplasms showing infiltrative invasion comprised of > 50% extracellular mucin [1]. In contrast to the pushing invasion of the LAMN, the infiltrative invasion is confined to destructive stromal invasion into the appendiceal wall. The histologic features of infiltrative invasion include infiltrative tumor cells, which exhibit cribriform, small tubules, or single cells accompanied by mucin within the desmoplastic stroma, and small dissecting mucin containing floating tumor cells but inconspicuous desmoplastic reaction [1,3,12]. The neoplastic epithelium in mucinous adenocarcinoma demonstrates high-grade cytology that may be only seen focally, are characterized by enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, increased mitotic figures, full-thickness stratification, and loss of nuclear polarity, which often extends to the luminal aspect of the epithelial cell.

Grading system of appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinoma

The PSOGI consensus panel has classified appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinomas and moderately and poorly differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma, similar to the grading system of nonmucinous adenocarcinoma in other gastrointestinal tracts [12]. However, the PSOGI consensus classification was not easy to apply to appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinomas. The AJCC 8th Cancer Staging Manual classified the appendiceal mucinous tumors as a three-tier grading system: G1 (well-differentiated), G2 (moderately differentiated), and G3 (poorly differentiated), based on cytologic features, tumor cellularity, and signet-ring components [13].

Appendiceal G1 (well-differentiated) tumors are low-grade cytology, usually lacking infiltrative invasion, and essentially refers to LAMN. Given that mucinous adenocarcinoma is characterized by infiltrative invasion and almost always exhibits at least focal areas of high-grade cytologic features, typical mucinous adenocarcinomas should be classified as either G2 (moderately differentiated) or G3 (poorly differentiated) tumors [3]. Mucinous adenocarcinomas often show complex architecture, such as cribriform and complex papillary structures. The presence of signetring cells is an indication of infiltrative mucinous adenocarcinoma. Poorly differentiated (G3) mucinous adenocarcinoma demonstrates infiltrative invasion, with most having signet-ring cells. Signet-ring cells, characterized by prominent intracytoplasmic mucin displacing the nucleus, may infiltrate single cells or as aggregates, classified as grade G3 (poorly differentiated). Most G3 tumors are almost entirely composed of signet-ring cells, while a minority of cases are composed of mixed signet-ring cells and glandular structures. If cancer comprises ≤ 50% signet-ring cells, the WHO terminology is mucinous adenocarcinoma with signet-ring cells or mucinous adenocarcinoma, poorly differentiated. If the tumor contains > 50% signet-ring cells, the WHO terminology is signet-ring cell carcinoma. The microscopic findings of high-grade (G2 and G3) appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinomas are demonstrated in Fig. 7.

Various histologic features of appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinoma and signet-ring cell carcinoma. (A) Mucinous adenocarcinoma presents within the appendiceal wall. (B) Moderately differentiated (G2) mucinous adenocarcinoma exhibits high-grade cytology and demonstrates infiltrating glands associated with desmoplastic stroma. (C) Mucinous adenocarcinoma markedly distorts the appendix with dissecting cellular pools present within the appendiceal wall. (D) Poorly differentiated (G3) mucinous adenocarcinoma demonstrates high-grade cytology and signet-ring cells. (E) Signet-ring cell carcinoma (G3, poorly differentiated) essentially replaces the entire wall of the appendix. (F) Neoplastic signet-ring cells are seen in single cells or small clusters within the dissecting mucin pools.

Most mucinous adenocarcinomas have clinically aggressive behavior, infiltrating through the appendiceal wall (pT4), and frequently metastasize to the abdominal or pelvic peritoneum at diagnosis. After an appendectomy specimen, diagnosis of mucinous adenocarcinoma should result in subsequent right hemicolectomy to evaluate lymph node metastases.

Ancillary tests of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms

A limited number of studies have reported that the vast majority of KRAS mutations occurred in G1 and G2 tumors [4,31-35], and most KRAS mutations occur in 50% to 60% of Tis(LAMN) [4]. These data suggest that KRAS mutations are important in tumor initiation but may be less critical for aggressive highgrade tumor progression. GNAS mutations, known as essential in abundant mucin production, are also presented in G1 and G2 tumors but less commonly in G3 tumors [31-35]. The co-mutation of GNAS and KRAS is identified in between 65% to 85% of cases [35,36]. Other minor mutations, including MET, PIK3CA, FAT4, AKT1, SMAD2, JAK3, STK11, and RB1 have been identified [33,37]. However, BRAF mutation, microsatellite instability (MSI), and DNA mismatch repair protein deficiency are rarely seen in LAMN [10,38].

DISSEMINATED PERITONEAL MUCINOUS DISEASE

Pseudomyxoma peritonei should be avoided in pathologic diagnosis

Pseudomyxoma peritonei, the clinical term for disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease, is a syndrome and applies to a neoplastic condition characterized by the grossly persistent accumulation of mucinous ascites in the peritoneal cavity [12]. The expansion of mucin within the abdominal cavity results from mucus following the normal flow of peritoneal fluid, redistribution of the mucin, and neoplastic cells [23]. Based on clinicopathological and immunohistochemical data, most cases are due to the perforation of AMNs [12,23,24,39,40]. Occasionally, mucinous neoplasms from other organs, including the colon, pancreas, ovary, and urachus, may also present with clinical appearances [12,23,24,39,40]. Immunohistochemical stains of cytokeratin 20 and CDX2 may be helpful in the diagnosis of the appendiceal origin (Supplementary Fig. S1). Clinically, abdominal discomfort, distention, intestinal obstruction, and often omental cake in which the omentum transforms into a firm mass can present within the intraabdominal cavity [4,9,41-43]. Given this, pseudomyxoma peritonei is a clinical term and used mainly by oncologists and radiologists; thus, it should not be used in histopathologic diagnosis [13]. The tendency of tumor cells from the appendix to produce abundant extracellular mucin shows slow infiltration into the peritoneum and underlying tissues with rare lymphovascular invasion relative to the overall tumor bulk [5]. Accurate diagnosis of AMNs and disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease is essential because management may include follow-up or radical treatment such as CRS-HIPEC [23].

Diagnostic terminology and classification of disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease

Ronnett et al. [9] classified disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease into three prognostically relevant categories: disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis (DPAM), peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis (PMCA), and PMCA with signet-ring cells [44]. However, the classification by Ronnett et al. [44] was not well established, leading to conflicting results. Given recent updates on diagnostic terminology, DPAM and PMCA are no longer recommended in pathology reports. Asare et al. [45] found that histologic grade was an independent predictor of survival in 25,992 patients with appendiceal cancer.

The PSOGI consensus panel has presented the diagnostic terminology for disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease: lowgrade mucinous carcinoma peritonei, high-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei, and high-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei with signet-ring cells are equivalent to the alternative terminology of DPAM, PMCA, and PMCA with signet-ring cells, respectively. The AJCC 8th Cancer Staging Manual has proposed terminologies accompanying grading based on the criteria of Misdraji et al. [13,46,47]. Misdraji [46] used the diagnostic terms directly from the appendiceal neoplasm into the peritoneum: LAMN (G1) with peritoneal involvement, mucinous adenocarcinoma moderately differentiated (G2), and mucinous adenocarcinoma poorly differentiated (G3). In addition, acellular mucin is classified separately. Davison et al. [4] determined that the three-tiered grading is the most important predictive factor of overall survival in patients with stage IV AMNs.

Grading system of disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease

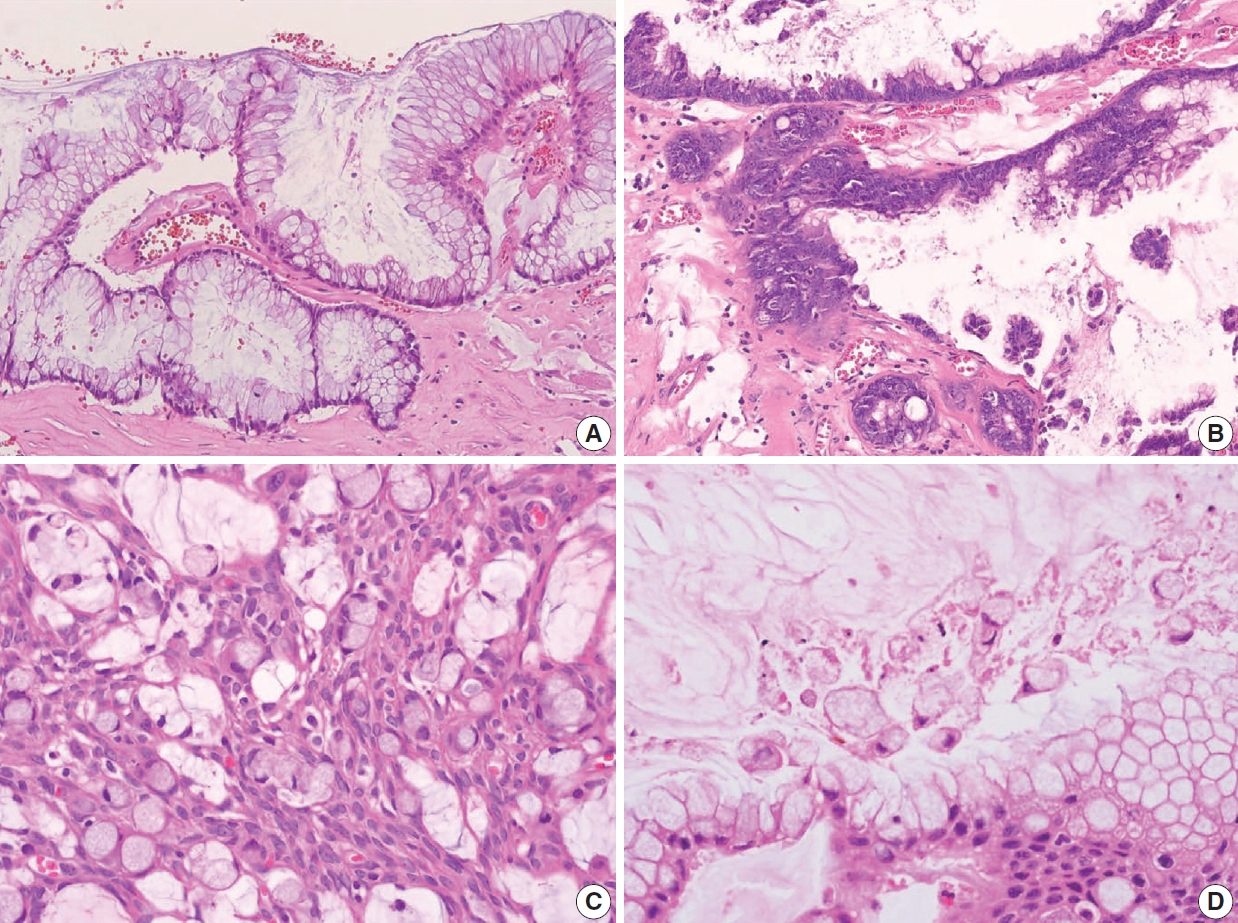

Low-grade (G1, well-differentiated) mucinous carcinoma peritonei, synonymous with a LAMN with peritoneal involvement, is defined as a mucinous neoplasm of low-grade cytology involving the peritoneum without infiltrative invasion or desmoplasia. Perineural and lymphovascular invasions are not seen. Typically, the neoplastic epithelial component accounts for less than 20% of the total mucin component. Low-grade (G1, well-differentiated) mucinous carcinoma peritonei almost always arises from a LAMN, so the AJCC 8th Cancer Staging Manual and Misdraji [46] proposed the term of LAMN with peritoneal involvement [13]. High-grade (G2, moderately differentiated) mucinous carcinoma peritonei, a synonym of moderately differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma, is defined as a disseminated peritoneal mucinous tumor by the presence of high-grade cytology in the absence of signet-ring cells. The high-grade cytology criteria correspond to moderately differentiated (G2) appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinoma or HAMN. These can demonstrate diffuse high-grade cytology or display a mixture of low- and high-grade cytology areas. The cytologic features may be heterogeneous with low-grade areas with high-grade cytology, and this heterogeneity needs generous sampling for histologic evaluation. Cribriform complex growth and infiltrating tubular structures associated with stromal desmoplasia can be seen. Davison et al. [4] defined the high tumor cellularity as > 20% of the mucinous component. High-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei with signet-ring cells (G3 tumor) shows high-grade cytology and invasive tumors with a signet-ring cell component, equivalent to poorly differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma. High-grade (G2 and G3) disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease can present destructive infiltrative invasion into the extra-appendiceal spread, peritoneum, or other organs, frequently associated with perineural and lymphovascular invasion. The microscopic findings of a disseminated peritoneal mucinous tumor are presented in Fig. 8.

Histologic features of disseminated peritoneal mucinous tumors. (A) A disseminated peritoneal mucinous tumor of low-grade (G1, well-differentiated) without destructive invasion. The tumor cells resemble those of low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm. (B) A disseminated peritoneal mucinous tumor of high-grade (G2, moderately differentiated) cytology. High-grade cytology corresponds to moderately differentiated (G2) mucinous adenocarcinoma. (C) High-grade (G3) mucinous carcinoma peritonei with signet-ring cells presents high-grade cytology and invasive signet-ring cell component, equivalent to the poorly differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma. (D) Isolated signet-ringlike cells float within mucin pools. Degenerating tumor cells or histiocytes may exhibit signet-ring-like morphology.

Diagnostic difficulty of disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease

The discordance grade may be presented between appendiceal and peritoneal tumors. The PSOGI consensus panel recommends that peritoneal grading should be used for staging purposes, as intraperitoneal grading is more likely to influence patient prognosis [3]. However, the CAP protocol advocates that more highgrade tumors between the appendix and peritoneum should be assigned to the tumor for staging. These diverse ideas can lead to diagnostic confusion and difficulty; thus, more advanced investigations concerning prognosis are required. Regarding the potential discrepancy between G2 and G3 tumors, Breadly and Carr [40] recommended that more than 10% of the signet-ring cell components should be identified in the diagnosis of G3 tumors. Because degenerating tumor cells or even histiocytes floating within mucin pools without destructive invasion may often exhibit signet-ring cell-like features (Fig. 8D). Sirintrapun et al. [48] reported that isolated signet cells within mucin pools are less prognostically significant than those found in invading tissue. We surveyed the best criterion of a focal lesion with signet-ring cells at the workshop, and the results are shown in Supplementary Data S2.

The pathologic grade is an independent prognostic factor in patients with stage IV mucinous appendiceal neoplasms. Patients with high-grade (G2 or G3) disseminated peritoneal mucinous tumors have significantly worse survival than patients with low-grade (G1) tumors. Therefore, for high-grade disseminated peritoneal mucinous tumors, systemic chemotherapy followed by the option of CRS-HIPEC is recommended according to the therapeutic response [4,45,49-52].

Biologic behavior codes of primary and metastatic tumors

The ICD-O3 code is 8480/6 in secondary disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease regardless of the grading; however, ICD-O3 is 8480/3 in the primary or unknown origin of disseminated peritoneal disease [53]. The histologic grade, behavior codes, diagnostic terminologies, and criteria for acellular mucin and disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease are summarized in Table 4. In addition, the checklist of standard data elements of the appendiceal epithelial tumors, including disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease, is presented in Table 5.

Histologic grade, behavior codes, terminology, and diagnostic criteria for secondary disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease

OTHER APPENDICEAL EPITHELIAL TUMORS

Non-mucinous adenocarcinoma and adenoma

Non-mucinous adenocarcinoma is less common than mucinous adenocarcinoma [1]. Uemura et al. [54] reported that nonmucinous adenocarcinoma is biologically distinct from the mucinous subtype and shows mostly moderate to poorly differentiated with frequent peritoneal metastasis. The histopathologic findings and tumor grading of non-mucinous adenocarcinoma are the same as conventional colorectal adenocarcinoma [1]. Non-mucinous adenocarcinoma demonstrates a high level of MSI. The frequency of KRAS mutation is similar in both colorectal adenocarcinomas and appendiceal non-mucinous adenocarcinomas, but the molecular pathogenesis is different [38,55,56]. The PSOGI panel prefers to confine “adenoma” to lesions that resemble conventional adenomas of the colorectum limited to the mucosa and intact muscularis mucosae without luminal dilatation or expansile growth pattern [12,23]. Based on this, appendiceal adenomas are uncommon, and many neoplasms that were previously reported as adenomas are now classified as LAMN or serrated lesions. For example, a villous lesion showing serration with conventional dysplasia and intact muscularis mucosae without pushing invasion should be called a serrated dysplasia rather than a villous adenoma. The WHO 5th Digestive System Tumors and CAP protocol recommend that appendiceal adenoma should be restricted to the precursor lesion of non-mucinous adenocarcinoma [1,14,22]. The histologic findings of non-mucinous adenocarcinoma arising in adenoma are presented in Fig. 9A–C.

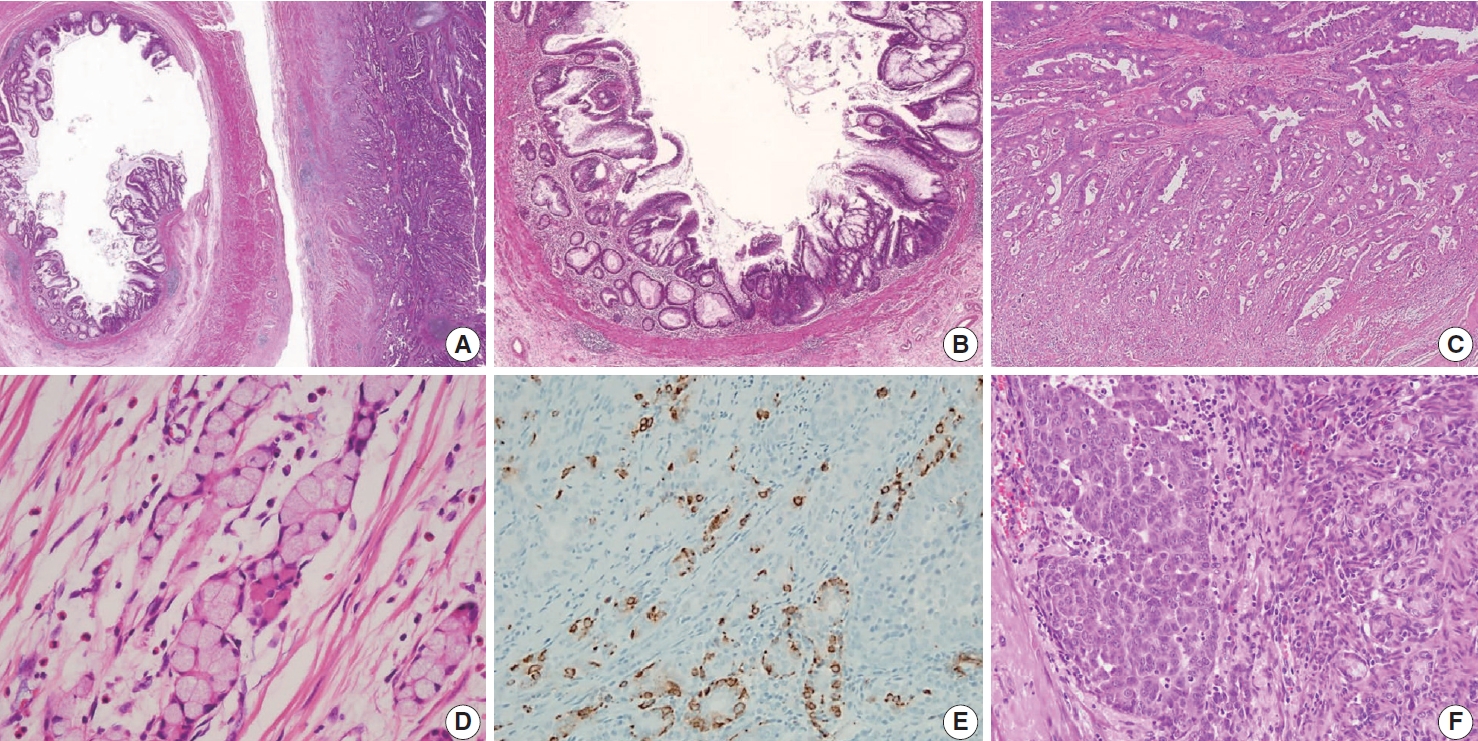

Histologic features of non-mucinous adenocarcinoma and goblet cell adenocarcinoma. (A) Co-existing adenoma and non-mucinous adenocarcinoma of the appendix. (B) Low-grade adenoma of the appendix resembles conventional adenoma of the colorectum. The mucosal architecture is well preserved with intact muscularis mucosae without a pushing invasion pattern. (C) Non-mucinous adenocarcinoma displays moderately differentiated and 50% to 95% gland formation. (D) Low-grade (G1) goblet cell adenocarcinoma shows small clusters composed of cohesive goblet cells and a few Paneth-like cells, displaying mostly low-grade patterns. (E) Low-grade (G1) goblet cell adenocarcinoma, immunohistochemistry of synaptophysin shows positive expression in neuroendocrine cells. (F) High-grade (G3) goblet cell adenocarcinoma displays >50% high-grade patterns.

Goblet cell adenocarcinoma

Goblet cell adenocarcinoma can occur almost exclusively in the appendix and is sometimes difficult to differentiate from AMNs and non-mucinous appendiceal tumors. Goblet cell adenocarcinoma, previously called goblet cell carcinoid or mucinous carcinoid, is a rare and aggressive tumor [1]. The tumor components are goblet-like cells and variable numbers of neuroendocrine cells and Paneth-like cells, and it is characteristically arranged as tubules similar to intestinal crypts [1]. The classic low-grade tumor displays tubular or clustered growth and small groups of cohesive goblet cells, whereas the high-grade tumor shows infiltrating tumor cells, convoluted anastomosing tubules, cribriform masses, irregular solid pattern, and large aggregates of goblet cells or signet-ring cells [57]. Nonaka et al. [58] found that neuroendocrine cells are inconsistent and not essential in the tumor component. For this reason, pathologists must find at least a focal lesion of classical low-grade tumor component to diagnose as a goblet cell adenocarcinoma.

Several classification and grading systems have been described. Tang et al. [59] classified goblet cell adenocarcinomas into three groups based on the histopathologic features: group A (typical goblet cell carcinoid), group B (adenocarcinoma ex-goblet cell carcinoid, signet-ring cell type), and group C (adenocarcinoma ex-goblet cell carcinoid, poorly differentiated type). Recently, the WHO 5th Digestive System Tumors classified goblet cell adenocarcinomas into a three-tiered grading system, based on the proportion of the tumor cells that consists of low-grade and highgrade patterns as follows: grade 1, > 75% of low-grade pattern or < 25% of high-grade pattern; grade 2, 50%–75% of low-grade pattern or 25%–50% of high-grade pattern; and grade 3, < 50% of low-grade pattern or > 50% of the high-grade pattern [1,60]. Nonaka et al. [58] reported that the high-grade component percentage was correlated with cancer-specific survival. The histological and immunohistochemical findings of goblet cell adenocarcinoma are presented in Fig. 9D–F. The pathogenesis remains entirely elusive. It is generally believed that it is derived from the pluripotent stem cells at the crypt base that can undergo dual glandular and neuroendocrine differentiation.

CONCLUSION

The GPSG-KSP presents a “Standardization of the Pathologic Diagnosis of the Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm.” This article focuses on the diagnostic criteria, terminology, grading, staging,biologic behaviors, treatment, and prognosis of AMNs and disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease. In addition, we propose a checklist of standard data elements of the appendiceal epithelial neoplasms. We hope that the present article will lead to the standardization of the pathologic diagnosis of AMNs and disseminated peritoneal mucinous disease and improvement in the communication between pathologists and between pathologists and clinicians.

Supplementary Materials

The Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2021.05.28.

Supplementary Data S1.

Workshop for the Standardization of the Pathologic Diagnosis of the Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm (I)

Supplementary Data S2.

Workshop for the Standardization of the Pathologic Diagnosis of the Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm (II)

Supplementary Fig. S1.

Stage IV appendiceal mucinous tumor with low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN) and disseminated peritoneal mucinous tumor.

Notes

Supplementary Information

The Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2021.05.28.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: MSC, JMK. Project administration: DWK, YNK, BHK, JYK, JMK, JK, HSK, DYP, HYP, JHS, SJL, WL, HSL, MSC, HKC, HJC, MYC, SYJ, YC, HSH. Supervision: BHK, JMK, JK, MSC, HJC. Writing— original draft: DWK. Writing—review & editing: JMK. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

H.S.L., a contributing editor of the Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by The Korean Society of Pathologists Grant No. 2018.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Jae-Hyun Ahn (SeongKohn Traders’ Company) for technical support of whole slide image scanning and online service. Whole slide images are available in online (http://dg.digitalpathology.co.kr/ExternalInterface/Viewlink?INST=INST_A&FA=FAC_B&ENC=Mq0sd5WKOfVTGWOpht1H8QhMt2fskenwse8wnOu3t9Rc5czHdfX3smwHgHd3_MghIeGuQR2V9bkDxEmPeX4HX2fEJuXWDILRYOAb_UuaUNQ).