Infections and immunity: associations with obesity and related metabolic disorders

Article information

Abstract

About one-fourth of the global population is either overweight or obese, both of which increase the risk of insulin resistance, cardiovascular diseases, and infections. In obesity, both immune cells and adipocytes produce an excess of pro-inflammatory cytokines that may play a significant role in disease progression. In the recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, important pathological characteristics such as involvement of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, endothelial injury, and pro-inflammatory cytokine release have been shown to be connected with obesity and associated sequelae such as insulin resistance/type 2 diabetes and hypertension. This pathological connection may explain the severity of COVID-19 in patients with metabolic disorders. Many studies have also reported an association between type 2 diabetes and persistent viral infections. Similarly, diabetes favors the growth of various microorganisms including protozoal pathogens as well as opportunistic bacteria and fungi. Furthermore, diabetes is a risk factor for a number of prion-like diseases. There is also an interesting relationship between helminths and type 2 diabetes; helminthiasis may reduce the pro-inflammatory state, but is also associated with type 2 diabetes or even neoplastic processes. Several studies have also documented altered circulating levels of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes in obesity, which likely modifies vaccine effectiveness. Timely monitoring of inflammatory markers (e.g., C-reactive protein) and energy homeostasis markers (e.g., leptin) could be helpful in preventing many obesity-related diseases.

Several investigators have reported that obesity or obesity-related complications appeared to be associated with increased risk of hospitalization of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients and death [1-3]. In general, overweight or obese persons are at higher risk for infections and respond poorly to therapies [4,5]. Being obese or overweight corresponds to a state of energy imbalance and is caused by inappropriate intake of energy-dense foods and physical inactivity. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 1.9 billion adults were overweight (body mass index [BMI], 25.0 to <30) in 2016; of these over 650 million were obese (BMI, 30 or higher). In addition, over 340 million children and adolescents aged 5–19 were overweight or obese in 2016. Elevated BMI is an important risk factor for various non-communicable diseases such as type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance, hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, osteoarthritis, and certain cancers such as postmenopausal breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and renal cell carcinoma. With increasing BMI, the risk for these diseases also increases.

Obesity and its intimately associated disorder– type 2 diabetes or insulin resistance – are associated with gradual alterations in cellular physiology. Many investigators believe that the poor outcomes observed in individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes/ insulin resistance are due to immune system dysfunction that is triggered by chronic low-grade inflammation present in both health problems [6]. Interestingly, these patients also are at increased risk of infections and mortality from sepsis. Recent data suggest that infections may precipitate insulin resistance via multiple mechanisms such as the pro-inflammatory cytokine response, the acute-phase response, and alteration of nutrient status [7]. In general, excessive adipose tissue in the body is known to hinder immune function, altering leucocyte counts as well as cell-mediated immune responses [8]. These immune cells are an intimate part of adipose tissue and an important source of proinflammatory cytokines/products, which ultimately contribute to the development of local adipose tissue inflammation and several metabolic complications [9].

In fact, adipose tissue acts as an endocrine organ; it secretes a number of hormone-like cytokines or adipokines, e.g., leptin, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, resistin, adipsin, and adiponectin among others. The majority of these adipokines participate in pro-inflammatory processes in obesity and perpetuate the state of insulin resistance [10]. Among these adipokines, several studies have suggested that leptin has an important role in major obesity-related health problems such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and different cancers [11]. Under normal conditions, leptin primarily maintains energy homeostasis through the central/hypothalamic anorexigenic pathway. However, in obesity, leptin possibly acts differently and supports a pro-inflammatory milieu. The long isoform of the leptin receptor (ObRb) may play a key role in both physiologic and pathologic conditions. Interestingly, both long and short forms of the leptin receptor are expressed by different immune cells, e.g., B-cells, T-cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, monocytes, and macrophages [12-14]. Therefore, leptin can modulate both innate and adaptive immune response. An appropriate understanding of the complicated network of infectious pathologies and immune responses in obesity would help to formulate novel preventive strategies.

CORONAVIRUS DISEASE, OTHER VIRAL INFECTIONS, AND OBESITY-RELATED PROBLEMS

During the last two decades, there have been three coronavirus disease outbreaks. The first was the 2002–2004 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV or SARSCoV-1) that emerged in China. A similar disease, caused by Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), was initially detected in Saudi Arabia in 2012. The latest coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) caused by SARS-CoV-2 began in December 2019 in China. The rapid spread of this infectious disease has been documented in different parts of the world, and about 6.7 million deaths have been recorded so far. SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped positive-sense single-stranded linear RNA virus; the envelope is coated with envelope (E) and membrane (M) proteins as well as a spike (S) glycoprotein that is responsible for binding to the host target cell receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2). In addition, other cellular components such as extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer/CD147, transmembrane serine protease 2, and ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 are implicated in viral endocytosis [15].

ACE catalyzes the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, which is an important step in the regulation of blood pressure via the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). Moreover, ACE acts on several biomolecules including bradykinin, encephalin, substance P, and amyloid β-peptide (Aβ), as well as in various physiological processes such as renal development, male fertility, hematopoiesis, and immune responses [16,17]. Conversely, ACE-2 is an important homolog of ACE and responsible for the conversion of angiotensin II to angiotensin 1-7, thereby counterbalancing ACE activity [18]. Both ACE and ACE-2 are cell membrane-anchored proteins, expressed in several organs, and functionally antagonistic to each other.

As mentioned earlier, to enter host cells, SARS-CoV-2 utilizes ACE-2 expressed in various organs, e.g., lung cells (pneumocytes and bronchial epithelium), gastrointestinal epithelium, and endothelial cells. Besides the lung parenchymal injury, there may be generalized endotheliitis (accumulation of lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages below the endothelium and in the perivascular spaces) [19]. In COVID-19, endothelial dysfunction is associated with the recruitment of immune cells and can result in many complications such as vasoconstriction, ischemia, inflammation, a pro-coagulant state, edema, and finally organ damage [20]. Moreover, abnormally increased levels of immune reaction and cytokines in different organs may cause a cytokine storm that can lead to additional organ dysfunction.

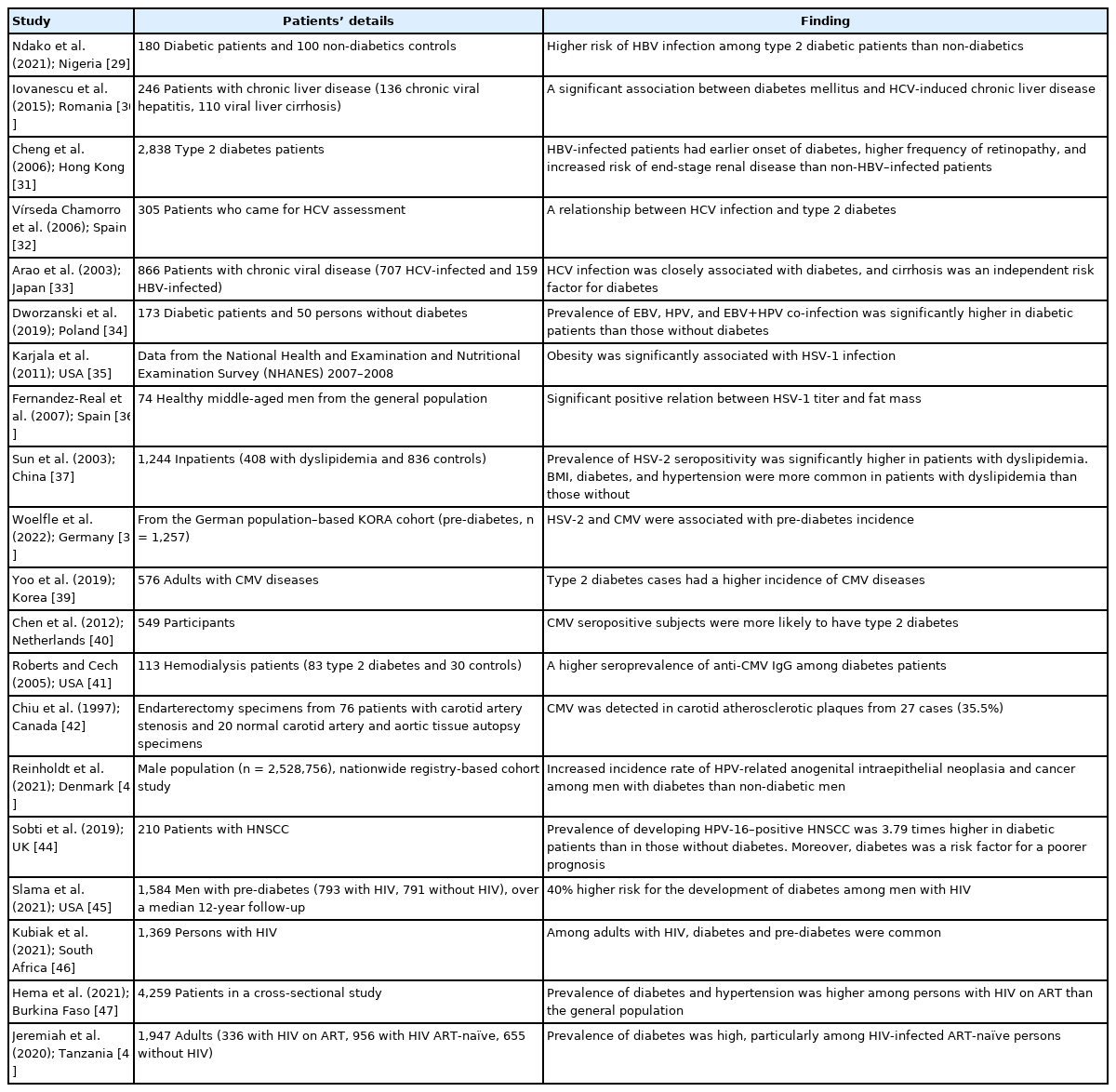

Obesity and insulin resistance are strongly connected to the activity of RAAS. Interestingly, expression of ACE-2, the functional receptor for viral entry, has been found to be higher in adipose tissue (and therefore higher in obesity) [21,22]. Furthermore, obesity and its complications such as hypertension, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes are associated with a higher risk of COVID-19 disease severity and mortality [22-24]. The impact of obesity and/or diabetes on SARS-CoV-1 infection has not been properly evaluated, although a few studies have investigated MERS-CoV–linked pathologies. One study of 32 MERSCoV infected patients observed that mortality was significantly correlated with both obesity and diabetes [25]. A meta-analysis of 637 MERS-CoV cases revealed that diabetes and hypertension were present in roughly 50% of the patients [26]. Additionally, in the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, obesity was also identified as an important risk factor for a poor prognosis [27,28]. In general, a number of reports have documented an association between type 2 diabetes and chronic viral infections (Table 1) [29-48].

In addition to the disrupted immune response in obesity, other plausible mechanisms responsible for the poor prognosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection include obesity-associated pre-existing endothelial dysfunction, a reduction in respiratory compliance, dysregulated lipid metabolism, and an overabundance of pro-inflammatory cytokines [20,22,49]. It is worth mentioning that obese individuals have defective/decreased responses to vaccination [49]. As a result, the combined effects of obesity and viral infection may worsen the existing status of cytokines, which normally coordinate the immune system and physiological homeostasis.

COVID-19–ASSOCIATED OPPORTUNISTIC FUNGAL DISEASES AND DIABETES

Generally, the majority of COVID-19 patients are asymptomatic or have minor symptoms. Less than 20% of cases require medical attention. According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH, USA), approximately 65% of individuals with serious illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection also had metabolic disorders such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and heart issues. Disease severity is associated with an uncontrolled immune response involving macrophages, neutrophils, different complement components, and a number of cytokines including TNF-α and interleukin-6 (IL-6). All these factors ultimately lead to a ‘cytokine storm’ and accompanying problems such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), widespread vascular inflammation, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Therefore, to prevent the aforementioned abnormal immune reactions, intervention with corticosteroids (like dexamethasone) has been considered [50]. Of note, apart from immune suppression, corticosteroid therapy can aggravate insulin resistance/type 2 diabetes, which is a risk factor for COVID-19 disease severity. Moreover, immune suppression can also allow the growth of opportunistic bacterial and fungal pathogens. Among hospitalized COVID-19 patients, investigators have isolated various bacterial strains such as coagulase-negative staphylococci, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, as well as a number of fungal agents including Candida albicans, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Cryptococcus neoformans [51-53]. Although Aspergillus and Candida species are commonly found in severely ill COVID-19 patients, studies have also documented other fungal pathogens. For example, researchers detected Histoplasma capsulatum complement fixation titers in patients with serious SARS-CoV-2 infection [53,54]. Other factors also thought to play a key role in fungal co-infection include hypoxemia/lack of tissue oxygenation, mechanical ventilation, and type 2 diabetes and associated hyperglycemia [55].

Inappropriately managed diabetes increases the risk of infection of various body organs. Furthermore, diabetes can hinder both innate and adaptive immune mechanisms [56]. In the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in India (roughly from March to July 2021), there was a mysterious outbreak of mucormycosis or black fungus infection among patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, and diabetic patients were more susceptible to mucormycosis [57]. In the normal immune system, all three complement activation pathways (classical, lectin, and alternative) play an important role protecting against fungal pathogens through mechanisms such as opsonization, humoral immune response stimulation, and chemotaxis of immune cells [58,59]. In diabetes, glycation of complement components (functional low levels) may lead to an impaired immune response [55,60]. Consequently, the impaired immune response in severe COVID-19 illness allows fungal infection.

OTHER NON-VIRAL PATHOLOGIES: PRION AND PRION-LIKE DISEASES

Prions or protease-resistant misfolded proteins are unusual protein aggregates (also termed amyloids/amyloid fibrils) that have a high proportion of β-sheets. The first prion identified was the PrP protein [61]. The gene encoding the normal cellular prion protein (PrPC, misfolded–PrPSc) is located on chromosome 20, and this glycoprotein is commonly present on the cell surface and can serve as a receptor for the Aβ peptide [62]. In addition, PrPC is expressed in different organs, particularly in the nervous and immune systems, and is thought to have numerous physiological functions such as cell surface scaffolding. Nevertheless, the mechanism of misfolding and aggregation into an abnormal prion-like conformation that again influences the misfolding of other associated protein copies in a self-propagating manner is indeed a unique biological process, and we can see this phenomenon even in yeast and fungi.

Apart from typical prion diseases, which include CreutzfeldtJakob disease (CJD), kuru, Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease, and fatal familial insomnia [63], there are other prion-like diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, type 2 diabetes, and amyloidosis. Certain proteins such as Aβ, tau, α-synuclein, and serum amyloid-A, which share some pathological characteristics with prions, have been implicated in these prion-like diseases [64,65]. For example, in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, aggregates of Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein can transmit the disease-pathology to experimental animals [65]. Of note, the fundamental features of Alzheimer’s disease lesions are the formation of Aβ in plaques and tau in tangles — both are β-sheet-rich misfolded variants of normal proteins.

Currently, about 50 different proteins are thought to form various human disease-related amyloid fibrils [66]. Furthermore, some of these abnormal proteins can cross species barriers and affect humans such as bovine spongiform encephalopathy or madcow disease, which is linked to variant CJD (vCJD) [67]. Interestingly, aggregation of amylin or islet amyloid polypeptide has been found in the pancreatic islets of Langerhans in individuals with type 2 diabetes [66]. In addition, patients with type 2 diabetes have an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Of note, a number of pathophysiological associations have been documented between Alzheimer’s disease and metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome [68]. On the other hand, both Alzheimer’s and prion diseases are neurodegenerative disorders, and there are several neuropathological commonalities and genetic connections between these diseases [69].

In humans, the most common prion disease is CJD with an incidence of about 1 case per 1 million population per year worldwide [70]. The majority (~85%) of cases of this rare disease occur sporadically, while ~10%–15% cases are due to familial or genetic mutations. The remaining cases (less than 1%) are linked to obvious environmental causes such as contaminated tissue transplant or surgical instruments (i.e., iatrogenic CJD) and contaminated meat consumption (i.e., vCJD). Another prion disease, kuru, once endemic in the Eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea, disappeared rapidly after the cessation of ritual cannibalism. Clinically, kuru has a prodromal phase and three stages. Interestingly, in the second stage, obesity is a common feature, which could also exist in early disease in association with bulimia [71]. However, unlike dissemination of microbial infections, prion disease is spread through ingestion or inoculation of contaminated materials (aside from sporadic and genetic inheritance). Therefore, different mechanisms by which conventional infectious diseases are spread, e.g., skin/mucosal contact, droplet/aerosol (airborne, coughs or sneezes), body fluids (like urine), fecal-oral route, vector-borne transmission, and fomites, have no role in the spread of prion diseases.

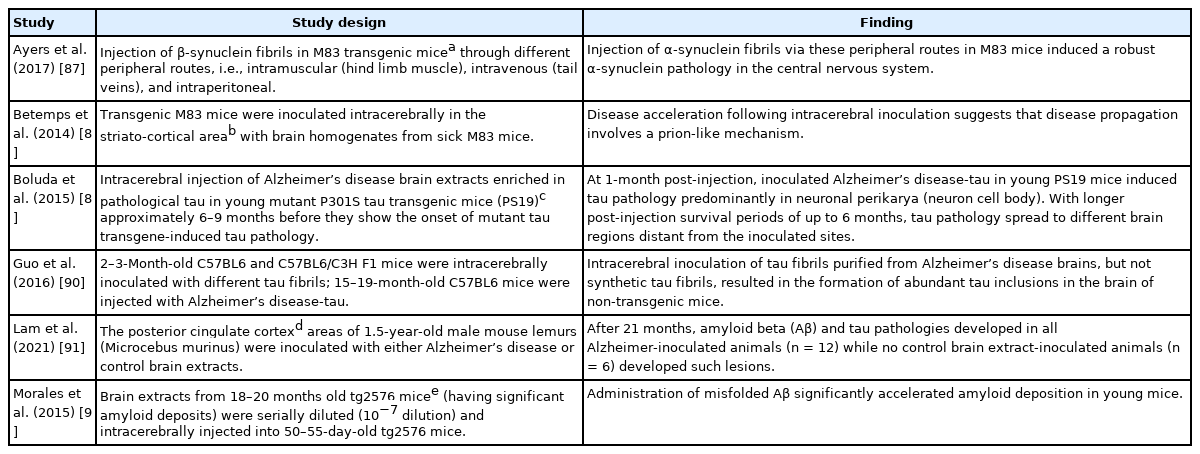

A number of investigators recorded an alteration of gut microbiota (dysbiosis) in prion disease and other neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease [72-76]. Gut microbiota dysbiosis has also been reported in obesity and metabolic disorders including type 2 diabetes [77-80]. Nonetheless, there is a close similarity between protein misfolding disorders and pathogenesis of prions (infectious/transmissible proteins). For example, misfolded Aβ and tau (of Alzheimer’s disease) spread in a way very similar to misfolded PrP [81-83]. As mentioned above, PrPC functions as a cell surface receptor for Aβ. Fascinatingly, PrPC acts in the propagation of prions as well as to transduce the neurotoxic signals from Aβ oligomers [82]. Experimentally, the transmission of kuru and CJD to various in vivo models has been performed by different laboratories [84-86]. Similarly, the pathologies of Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein could be transmitted in a prion-like manner to in vivo models by injecting the misfolded proteins. In this connection, the results of selected studies have been mentioned briefly in Table 2 [87-92].

Selected observations that displayed prion-like transmission characteristics of the most common neurodegenerative disease-related proteins

Both in vitro and in vivo studies have identified a number of compounds that have anti-prion activity. Congo red, polyanionic glycans, quinacrine, and compB either inhibit the formation of PrPSc or enhance the degradation of PrPSc. Interestingly, in experimental studies, anle138b (a recently developed drug) has been documented to inhibit the formation of pathological aggregates of α-synuclein (Parkinson’s disease) and tau (Alzheimer’s disease) proteins in addition to inhibiting aggregation of prion protein (PrPSc) [93,94]. A clear understanding of protein misfolding and its association with metabolic disorders at the molecular level may provide insights into their precise pathogenesis and result in the development of prevention strategies. Furthermore, early diagnosis (preferably in the preclinical stage) and prompt intervention are critical when there are few pathological protein aggregates in the brain. Accordingly, identification of appropriate early diagnostic markers is essential.

PARASITES IN OBESITY-RELATED PATHOLOGIES

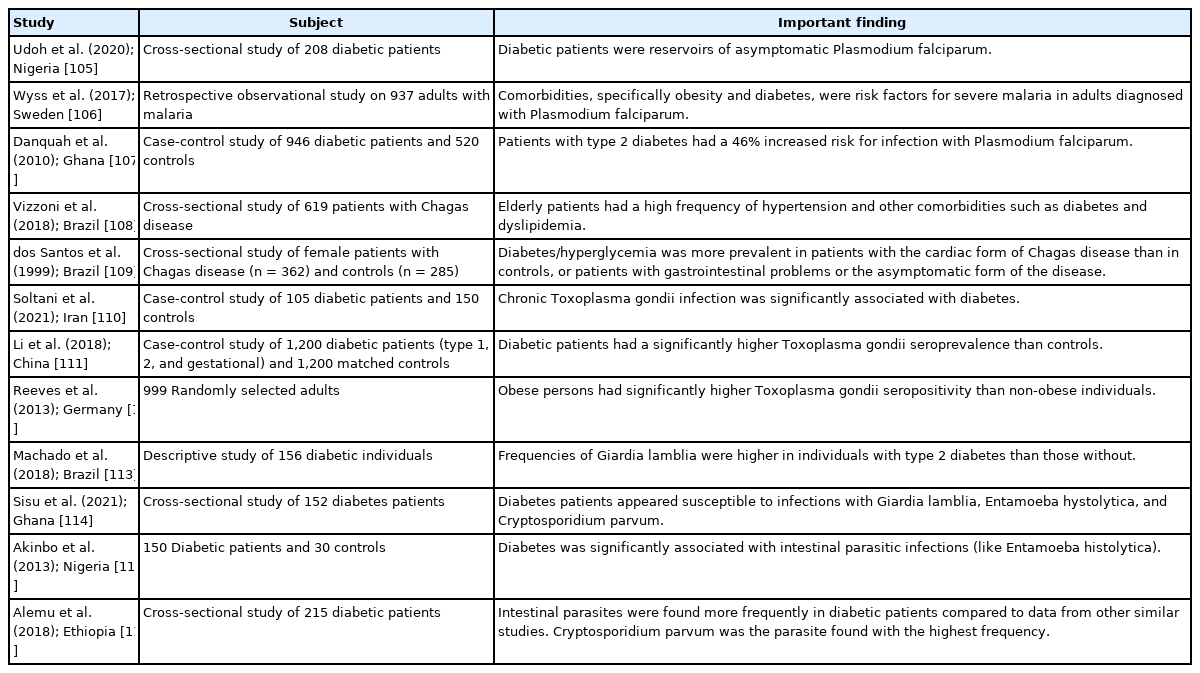

Parasitic infestations can have a diverse range of consequences/ sequelae. Ryan et al. [95] posited that helminth-related anti-inflammatory mechanisms may be beneficial. Lifestyle-linked chronic diseases usually have a strong connection with inflammation. In this context, hookworm species, particularly Necator americanus, may have a protective effect in inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis as well as in celiac disease. In addition, these authors reported an inverse association between human helminth infection and insulin resistance/type 2 diabetes. In an experimental study on male C57BL/6 wild-type mice, infection with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (rodent hookworm) significantly decreased various diabetes-associated parameters such as fasting blood glucose and weight gain [96]. Similarly, studies in human subjects have demonstrated that infection with Strongyloides stercoralis (threadworm) can reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes by modulating the expression of different pro-inflammatory cytokines [97-99]. A study from Thailand showed that Opisthorchis viverrini (liver fluke) infection had a protective effect against hyperglycemia and metabolic disease risk [100]. In contrast, many studies have reported that individuals with parasitic diseases are more susceptible to diabetes or that diabetic persons are at higher risk of infection with various parasites, e.g., Ascaris lumbricoides, Echinococcus granulosus, Enterobius vermicularis, Schistosoma mansoni, S. haematobium, Hymenolepis nana, hookworm, and Taenia species, as well as protozoan parasites such as Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, and Cryptosporidium species (Table 3) [101-116]. Some of these helminths are also considered to be responsible for cancer development. For example, S. haematobium can induce squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder, and O. viverrini may cause cholangiocarcinoma/bile duct cancer [117]. Unprecedentedly, a report revealed the dissemination of cancer cells from H. nana to different organs of a human host [118].

Selected studies that recorded a positive association between metabolic disorders and protozoan parasites

Two major types of primary liver cancer, i.e., hepatocellular carcinoma (~75% of all liver cancers) and cholangiocarcinoma (10%–20% of cases), are uniquely linked to a diverse group of risk factors namely viral hepatitis (hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus), obesity, type 2 diabetes, alcohol consumption, smoking, and toxic substances including aflatoxins produced by Aspergillus species. Moreover, risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma are inflammatory bowel disease, parasitic infections, and hepatolithiasis. Along with O. viverrini, infection with Clonorchis sinensis (another liver fluke) can cause the development of cholangiocarcinoma, particularly in Southeast Asia [119]. In addition, C. sinensis and A. lumbricoides may promote hepatolithiasis [119,120]. Interestingly, the co-occurrence of O. viverrini infection and diabetes has been shown to be associated with hepatobiliary tract damage and malignant transformation [121,122].

For helminthic infestations that are predominantly connected with tissue migration, numerous studies have documented the presence of peripheral eosinophilia (or increased number of eosinophils in the peripheral blood) or Loeffler’s syndrome (i.e., accumulation of eosinophils in the lung) [123,124]. Although eosinophils play a significant role in various physiologic processes including innate and adaptive immunity, data on the precise role of human eosinophils in defense against helminths are limited. Data on the specific anti-parasitic role of mast cells and basophils, which behave functionally similar to eosinophils in hypersensitivity/allergic inflammation, are also inadequate [125-127]. By contrast, there is a growing body of evidence that neutrophils play a protective role against several parasitic infections such as E. histolytica, Leishmania, and Plasmodium infections [128-130]. Neutrophils may clear the parasites by a number of mechanisms including phagocytosis, generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and formation of neutrophil extracellular traps.

IMMUNE CELLS IN OBESITY

White blood cells (WBCs or leukocytes) are fundamental components of the immune system. Several studies have reported a quantitative increase in WBCs among obese people [131-133]. A major component of the observed increase in WBC counts is neutrophils. In peripheral blood, more than half of the WBCs (up to about 70%) are neutrophils. It is notable that these cells are present in marginated (recoverable part) and circulating pools in almost equal proportions, while circulating cells have a remarkably short lifespan. Nonetheless, along with increased WBC counts, many investigators have noticed significantly higher levels of neutrophils in obese people [134-136]. Neutrophils from obese subjects have also been found to be functionally more active than neutrophils from lean controls. In obesity, the levels of neutrophil-released superoxides are significantly greater than in normal controls [137]. Apart from an elevated leukocyte count and release of ROS like superoxide (i.e., oxidative burst), the lymphocyte count is also elevated in obesity. In a communitybased study of 116 obese women, investigators found that obesity was connected with an increase in certain lymphocyte subset counts, excepting natural killer (NK) and cytotoxic/suppressor T cells [138]. Multivariate analyses of 322 women who were longitudinally followed from 1999 through 2003 revealed that increasing body weight was independently related to higher WBC, total lymphocyte, CD4, and CD8 counts [139]. Similarly, a study of 119 Saudi female university students showed that both BMI and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) were significantly correlated with WBC, neutrophil, and CD4 lymphocyte counts [140]. Furthermore, in a cross-sectional, retrospective study of 223 participants (female- 104), BMI was found to have a significant positive relationship with WBC, neutrophil, and lymphocyte counts [141]. These findings indicate that being overweight or obese may impact both innate and adaptive immune responses to numerous pathophysiological phenomena including infections by various pathogens.

Obesity is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation. A relatively inexpensive method to assess the systemic pro-inflammatory state is to determine the blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) [142]. It is believed that this parameter also indicates the stress situation of our body. A healthy range is between 1 and 2; values more than 3 or less than 0.7 in adults are pathognomonic [142]. In a study that compared NLR between obese individuals with insulin resistance (n=46) and those without (n=51), both the neutrophil count and NLR were found to be significantly higher in the insulin resistance group [143]. It is worth mentioning that insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes, which is a common sequela of obesity, is also associated with elevated total and differential WBC counts [131,132,144]. In a study of 600 subjects (BMI: 27.9±4.7) selected from 474,616 patients who visited Severance Hospital, Seoul, South Korea between January 2008 and March 2017, NLR was significantly associated with intra-abdominal visceral adipose tissue volume [145]. In addition, WBCs and levels of the serum inflammatory marker high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) were strongly correlated with visceral adipose tissue. In a cross-sectional study in Taiwan, a total of 26,016 subjects with metabolic syndrome were recruited between 2004 and 2013 [146]. Of note, the American Heart Association criteria for metabolic syndrome are central obesity, hypertension, high blood glucose and triglycerides, and lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the blood. In this study, obesity and related anthropometric parameters such as WHR were positively associated with NLR and C-reactive protein (CRP) in both sexes. Another study of 1,267 subjects (1,068 female and 199 male) collected from the out-patient clinic of Düzce University Hospital, Turkey during 2012–2013 reported that while WBC, neutrophil, and lymphocyte counts as well as level of hs-CRP exhibited a significant interrelationship with BMI, BMI was not correlated with NLR [147]. NLR may not be a better pro-inflammatory indicator than CRP or hs-CRP. Nonetheless, a different study from Turkey of 306 morbidly obese subjects (BMI ≥40) demonstrated significantly higher NLR levels in these subjects than normal controls [148]. Moreover, the authors concluded that elevated NLR was an independent and strong predictor of type 2 diabetes in morbidly obese individuals. A cross-sectional study from the 2011–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 2011–2016, a US population database) recorded a positive association between BMI and NLR in healthy adult female participants (n=3,201) [149]. The above studies indicate that being overweight or obese is linked with certain circulating markers that can be used affordably to evaluate systemic inflammatory status.

Lymphocytes (T-cells, B-cells, NK cells) play a significant role in obesity-linked inflammation [150]. A study from Germany revealed an impaired NK cells phenotype and subset alterations in obesity [151]. Another study of 169 subjects demonstrated an increase in total lymphocytes along with granulocytes and a decrease in the NK cell population among persons with metabolic syndrome and increased visceral adipose tissue [152]. Furthermore, an increase in memory cells was also documented in those subjects with an increased BMI and visceral adipose tissue. Impaired B-cell and T-cell function has been observed in high-fat (HF) diet-induced obese mice [153].

In HF diet-induced obese C57BL/6J female mice, investigators noted higher circulating monocytes in the HF group than the standard chow diet-fed mice [154]. Likewise, a number of studies involving human subjects have recorded an increased monocyte count in obese individuals [132,138,155,156]. However, other studies found no correlation between BMI and blood monocyte count [140,151]. Monocytes are the largest cells in our blood and normally up to 10% of WBCs are monocytes. Monocytes can be classified into three categories depending on their surface receptors: classical (CD14+), intermediate (CD14+ and low levels of CD16+), and non-classical (CD16+ along with lower levels of CD14+). In a study of 58 obese subjects and 25 metabolically healthy lean controls, numbers of both intermediate and non-classical monocytes were higher in obese subjects than lean controls [157]. Interestingly, these investigators also found that the levels of intermediate monocytes were positively and significantly related with the obese group’s serum triglyceride levels and mean blood pressure. Monocytes can differentiate into macrophages after migration to different tissues of our body— therefore, macrophages are present in the extracellular space. A number of reports have confirmed the accumulation of macrophages in the excess adipose tissue of obese individuals [157-159]. These infiltrated macrophages in adipose tissue create an inflammatory environment due to their production of several pro-inflammatory molecules. Consequently, macrophage infiltration and adipose tissue inflammation are important pathological processes that contribute to systemic inflammation and various complications such as insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome.

INFLUENCE OF OBESITY ON VACCINE EFFECTIVENESS

The efficacy and effectiveness of any vaccine varies considerably and no vaccines can provide 100% protection. According to the WHO, vaccine effectiveness is associated with a number of factors including age, gender, ethnicity, and other accompanying health conditions. The efficacy of a vaccine is evaluated by estimating the development of disease among vaccinated people in comparison with a placebo/control group in controlled clinical trials (i.e., ideal conditions). Conversely, vaccine effectiveness refers to how a vaccine actually performs in different populations.

The basic biological mechanisms underlying vaccine non-responsiveness are not well known. However, there is evidence that both carbohydrate and fat metabolic pathways are involved in responsiveness to vaccines [160]. Furthermore, obesity has been proposed to be associated with inadequate vaccine responsiveness [161]. Apart from well-established health-related problems such as insulin resistance and hypertension, the obesity-related chronic low-grade inflammatory state has adverse effects on the immune system [162]. Obviously, more research is needed to understand the effects of obesity on vaccine effectiveness.

POTENTIAL INDICATORS OF OBESITY AND INFLAMMATION

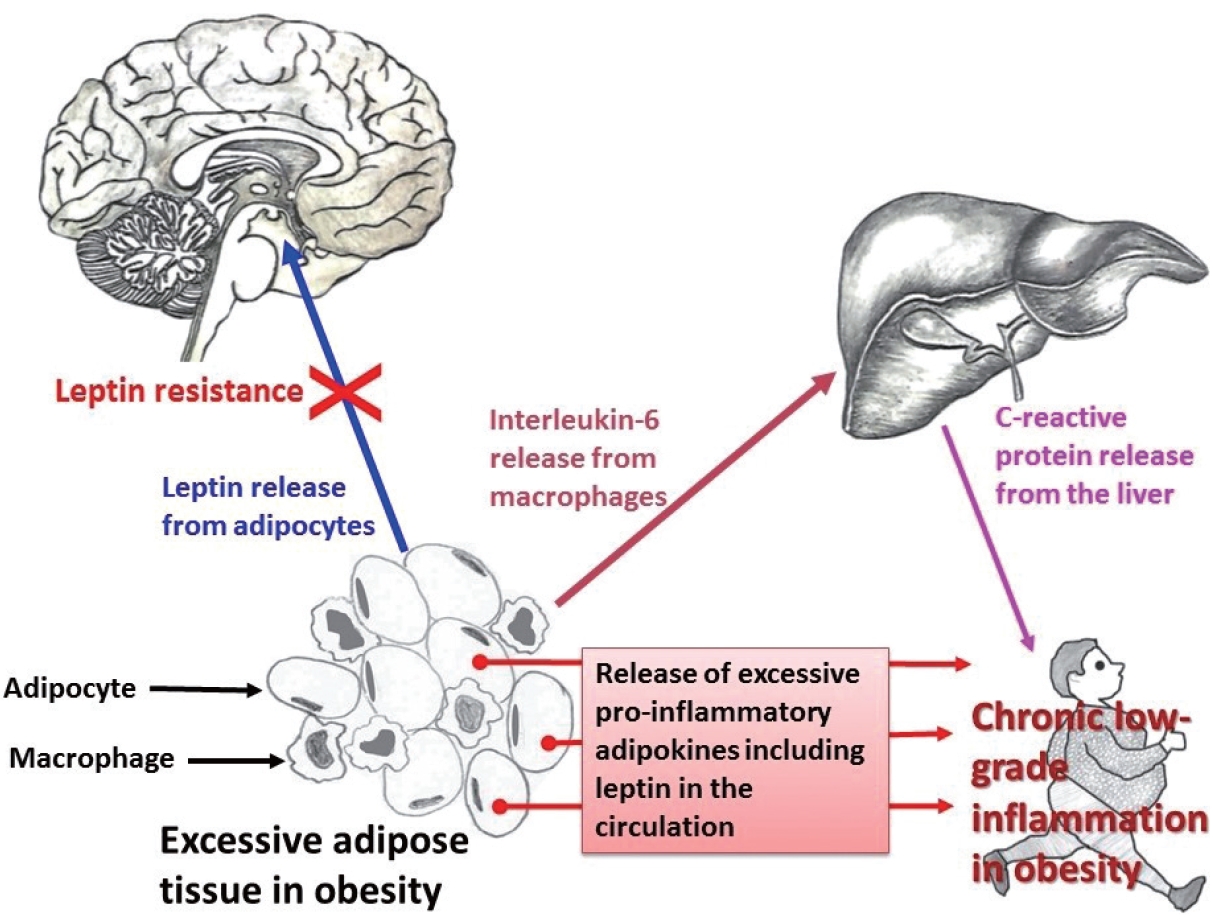

Obesity and CRP have been demonstrated to be positively correlated [163]. Furthermore, CRP is widely used as a marker of inflammation. Along with its role in inflammation, CRP also functions significantly in host defense against different pathogenic organisms [164]. CRP is present in at least two distinct forms: pentameric and monomeric (mCRP) isoforms, which have diverse activities and functional characteristics. Dissociation of the pentameric group into monomeric forms occurs at sites of inflammation and the monomeric form then may participate in local inflammation. CRP is primarily produced by the liver and its blood levels may increase from 0.8 mg/L (approximate normal value) to more than 500 mg/L in inflammatory conditions [165]. However, CRP is involved in several pathophysiological processes such as activation of the complement system, phagocytosis, promotion of apoptosis, release of nitric oxide (NO), and biosynthesis of various cytokines particularly pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-6 [166]. In addition, it is believed that mCRP can stimulate the process of chemotaxis and recruitment of circulating WBCs to sites of inflammation. Studies have documented associations (both positive and negative) between CRP and various hormone-like cytokines (adipokines) that are released from adipose tissue [167-169]; in particular, with the pro-inflammatory adipokine leptin (Fig. 1).

Relationship among pro-inflammatory adipokines, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and C-reactive protein (CRP) in obesity. Infiltration of macrophages in excess adipose tissue is a common phenomenon. The pleiotropic pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6, secreted by monocytes/macrophages, induces the biosynthesis of CRP from the liver.

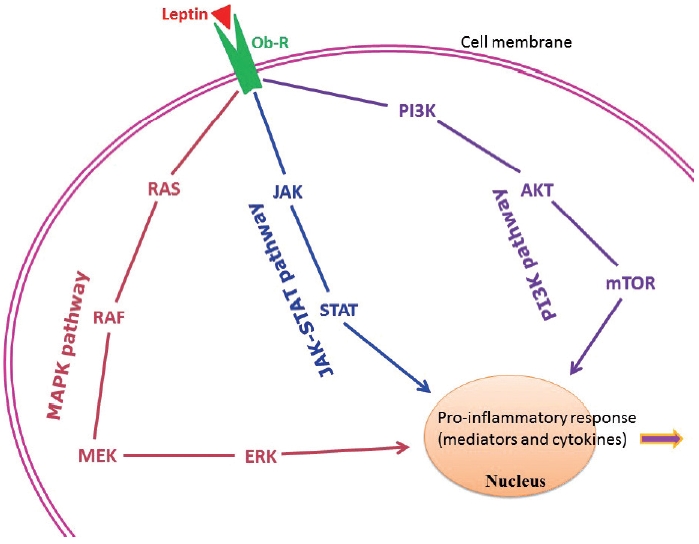

Adipose tissue behaves like an endocrine organ. As mentioned earlier, several hormone-like cytokines or adipokines are secreted from adipose tissue or fat cells. In general, the majority of these adipokines are pro-inflammatory, for example, leptin, visfatin, and resistin. However, a few anti-inflammatory adipokines such as omentin, apelin, and adiponectin are also secreted. Nevertheless, the majority of published studies have focused mainly on two adipokines– pro-inflammatory leptin and anti-inflammatory adiponectin. These two adipokines are involved in a number of biological mechanisms both under normal health conditions as well as under pathological circumstances. Interestingly, both adipokines are closely linked with our immune system. Leptin is a 16-kD protein produced primarily by adipocytes. Its main function is maintenance of energy homeostasis through regulation of the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. Leptin is associated with both innate and adaptive immune responses [170]. This adipokine has a close connection with inflammatory molecules including IL-6, TNF-α, NO, eicosanoid, and cyclooxygenase (particularly cyclooxygenase 2) [171], as well as intracellular signaling pathways connected with inflammation such as mitogen-activated protein kinase, Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription, and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (Fig. 2). In addition, leptin promotes chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and release of ROS [170,172].

Principal intracellular signaling pathways of leptin in connection with the chronic low-grade inflammatory state found in obesity. AKT, protein kinase B/serine-threonine kinase; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; JAK, Janus kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; mTOR, mechanistic/mammalian target of rapamycin; Ob-R, leptin receptor; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription.

Higher circulating levels of both leptin and CRP have been demonstrated to be correlated with disease severity and poor prognosis in patients with COVID-19 [173-175]. In a recently published report from Italy, COVID-19 patients with pneumonia had increased circulating levels of leptin and IL-6 and lower adiponectin levels than age- and sex-matched healthy controls [176]. Similar findings were documented in another study from the Netherlands [177]. In contrast, a group of investigators hypothesized that increased blood levels of leptin could be due to patients’ obesity and unrelated to disease pathology [178,179]. A number of mechanisms have been proposed to explain the poor prognostic role of leptin in COVID-19. van der Voort et al. reasoned that SARS-CoV-2 infection, by inducing higher leptin production, might overactivate leptin receptors in pulmonary tissue, ultimately enhancing local inflammation in the lungs [177]. Higher leptin levels could also activate monocytes and thus upregulate the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in monocytes, resulting in dysregulation of immune responses, finally leading to ARDS and multiple organ failure [173,180]. As mentioned earlier, leptin receptors are present in all immune cells. Therefore, leptin may affect the functions of these cells. Understanding the precise role of leptin and its interactions with different adipokines (both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory) and other classical hormones such as insulin, insulin-like growth factors, and estrogen, will help elucidate the relationships between obesity-related problems and immune mechanisms.

CONCLUSION

The recent COVID-19 pandemic has renewed interest in infectious diseases, and the disease pathology itself is a meeting place of both communicable and non-communicable diseases. For this reason, many authors have described the grave situation of 2020 and 2021 as ‘double pandemics’– the pandemic of COVID-19 and the long-continued global problem of obesity [1,181,182]. Apart from bacterial and fungal infections that are a common occurrence in obesity-related health conditions like type 2 diabetes, a number of prion-like diseases have a close link with these metabolic disorders. Regular assessment of a few markers such as CRP and leptin and adjustment of lifestyle factors could help protect against pathogens as well as metabolic diseases.

Notes

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available in the [MEDLINE] repository.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AR. Data collection and assembly: RP. Formal analysis: KJN. Project administration: MJLB, RP. Supervision: MJLB, RP. Writing— original draft: AR, MJLB. Figures: KJN. Writing—review & editing: RP, KJN, AB. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding to declare.