Elevated expression of Axin2 in intestinal metaplasia and gastric cancers

Article information

Abstract

Background

The Wnt signaling pathway regulates crucial cellular processes, including stem cell development and tissue repair. Dysregulation of this pathway, particularly β-catenin stabilization, is linked to colorectal carcinoma and other tumors. Axin2, a critical component in the pathway, plays a role in β-catenin regulation. This study examines Axin2 expression in normal gastric mucosa and various gastric pathologies.

Methods

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue samples from normal stomach, gastritis, intestinal metaplasia (IM), and gastric carcinoma were collected. Axin2 and β-catenin expression were evaluated using RNA in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry, respectively. Histo-scores (H-scores) were calculated to quantify expression levels of Axin2. Associations between Axin2 expression and clinicopathological variables were examined.

Results

Axin2 expression was examined in normal stomach, gastritis, and IM tissues. Axin2 expression was mainly observed in the surface and isthmus areas in the normal stomach and gastritis, whereas Axin2 expression was markedly higher at the bases of IM. Axin2 H-scores were significantly elevated in IM (mean ± standard deviation [SD], 87.0 ± 38.9) compared to normal (mean ± SD, 18.0 ± 4.5) and gastritis tissues (mean ± SD, 33.0 ± 18.6). In total, 30% of gastric carcinomas showed higher Axin2 expression. Axin2 expression did not have significant associations with age, sex, Lauren classification, histological differentiation, invasion depth, and lymph node metastasis. However, a strong positive correlation was observed between Axin2 and nuclear β-catenin in gastric carcinomas (p < .001).

Conclusions

Axin2 expression was significantly increased in IM compared to normal and gastritis cases. In addition, Axin2 showed a strong positive association with nuclear β-catenin expression in gastric carcinomas, demonstrating a close relationship with abnormal Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

Wnt signaling serves a variety of critical functions in the human body, orchestrating the regulation of stem cell development, cell differentiation, proliferation, immune cells and tissue repair and regeneration [1,2]. Delicate and various communication mechanisms exist between the Wnt protein and a receptor called Fizzled, to facilitate the precise execution of biological roles in a coordinated manner. Wnt signaling is classified into canonical and noncanonical pathways [3]. Inappropriate activation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway contributes to colorectal carcinoma and a variety of other tumors [4]. The stabilization of β-catenin is a key regulatory step during cell fate changes and transformations to tumor cells [5].

The axis inhibition protein 2 (Axin2) is a crucial component of the cytoplasmic complex that targets β-catenin for degradation in the absence of ligand [6]. In the absence of Wnt ligand, cytoplasmic β-catenin is degraded; degradation depends on a destruction complex that includes Axin2, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), casein kinase 1 (CK1), and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β). When Wnt proteins bind the Frizzled and LRP5/6 coreceptors, Axin2 is removed from the destruction complex, and stable β-catenin moves to the nucleus where, in combination with LEF/TCF DNA binding proteins, it activates target gene expression. In the presence of Wnt ligand, the Wnt signaling pathway induces dephosphorylation of Axin2, and the dephosphorylated Axin2 binds β-catenin less efficiently compared to its phosphorylated form [5]. The molecules that inhibit the activity of tankyrase reduce Wnt slignaling in carcinoma cell lines, and it has been suggested that they provide a new option for therapy for Wnt-based tumors [7]. Axin2 mutation have been reported in a variety of human carcinomas including hepatocel-lular carcinomas and colorectal carcinomas [8-10].

Axin2 operates as a scaffold protein within the Wnt signaling pathway [11]. Prior investigations have explored Axin2 mutations in connection with gastric carcinoma (GC) [12]. Nonetheless, the differences in Axin2 expression, encompassing both the spatial distribution and intensity, among normal tissue, gastritis, intestinal metaplasia (IM), and GC, have not been investigated. In this study, we aim to thoroughly examine the expression of Axin2 in various gastric pathologies and particularly evaluate its significance in GC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue samples

The samples were collected from patients with gastric carcinomas who underwent surgical resection at Jeju National University Hospital (JNUH) in Jeju, Korea, between 2012 and 2017, including GC (n = 56), IM (n = 10), chronic gastritis (n = 5), and normal (n = 5) gastric samples. Inflammation in the gastric mucosa was graded according to the Sydney classification and we considered the cases as chronic gastritis when inflammation grade is moderate or marked. The classification of histological subtypes of carcinomas was independently determined by two pathologists (D.H.L. and B.J.). For GC cases, we gathered clinical and pathological data, including age, sex, Lauren classification, histological grade, invasion depth, and lymph node metastasis.

Tissue array construction

Total five tissue microarrays (TMAs) were constructed; four TMAs included 96 cores from GC cases and 20 cores from noncancerous gastric lesions. In brief, representative tumor portion was carefully selected from hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides through histologic examination. Each representative tumor portion comprised more than 70% of the cell population. The 4-mm diameter core tissues were obtained from individual GC paraffin blocks and non-cancerous block. Then, these core tissues were arranged in a new recipient paraffin block (tissue array block) using a trephine apparatus (SuperBioChips Laboratories, Seoul, Korea).

Immunohistochemistry and interpretation

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) targeting β-catenin was conducted on 4-μm sections of the TMAs. IHC was done with the BOND-MAX automated immunostainer and a Bond Polymer Refine Detection kit (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. The primary antibody used was anti–β-catenin (1:800, catalog number 17C2, Novocastra Laboratories, Newcastle, UK). Positive nuclear β-catenin staining was defined as cases where more than 10% of tumor cell nuclei displayed strong staining for β-catenin.

Axin2 RNA in situ hybridization and interpretation

To detect Axin2 mRNA, we applied RNAscope kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Hayward, CA, USA) with unstained tissue slides according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each tissue section underwent pretreatment involving heat and protease application before hybridization with a specific Axin2 probe. A horseradish peroxidase-based signal amplification system was hybridized to the probe, followed by color development using 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride. The housekeeping gene ubiquitin C was employed as a positive control, and the bacterial gene DapB served as a negative control. The patterns of brown punctate dots present in nucleus and/or cytoplasm interpreted positive staining. Axin2 expression was quantified according to the five-grade scoring system (grade 0: no staining, grade 1: 1–3 dots/cell, grade 2: 4–10 dots/cell, grade 3: > 10 dots/cell, grade 4: > 15 dots/cell with > 10% of dots in clusters) [13]. The grade and percentage of tumor cells expressing Axin2 were measured, and histoscores (H-scores) were calculated by multiplying the grade (range, 0 to 4) and percentage of Axin2-positive tumor cells (range, 1 to 100), ranging from 0 to 400. For statistical analysis, H-score of 68 was chosen as cutoff value based on the mean value of Axin2 H-score (H-score, 68); the tumor was defined as high when Axin2 H-score is higher than 68.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) statistical software ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Prism ver. 9.0.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). We analyzed the association of Axin2 with clinicopathological features with the Pearson χ2 test. The correlations between the Axin2 H-scores and β-catenin expressions were evaluated by the Spearman correlation test. Difference was considered significant when p < .05.

RESULTS

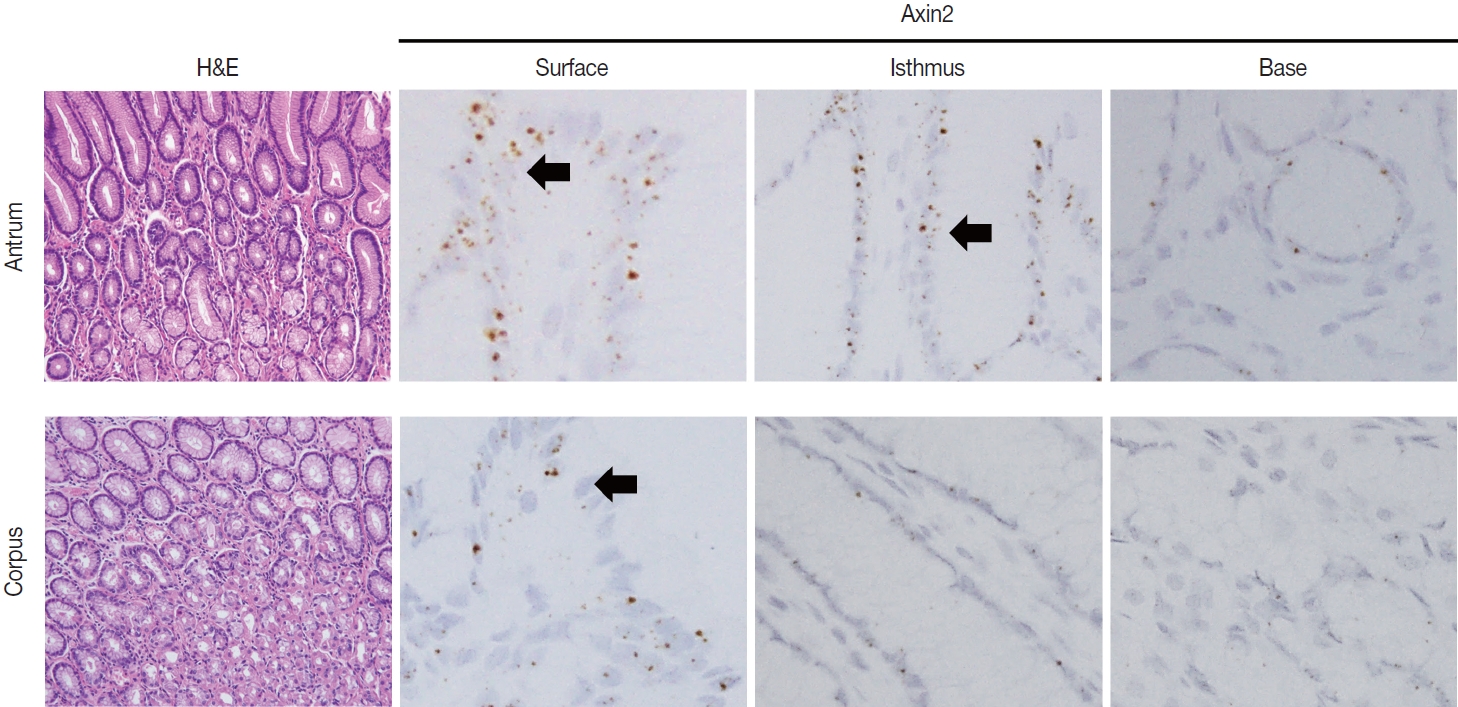

Axin2 expression in the normal gastric mucosa with or without inflammation

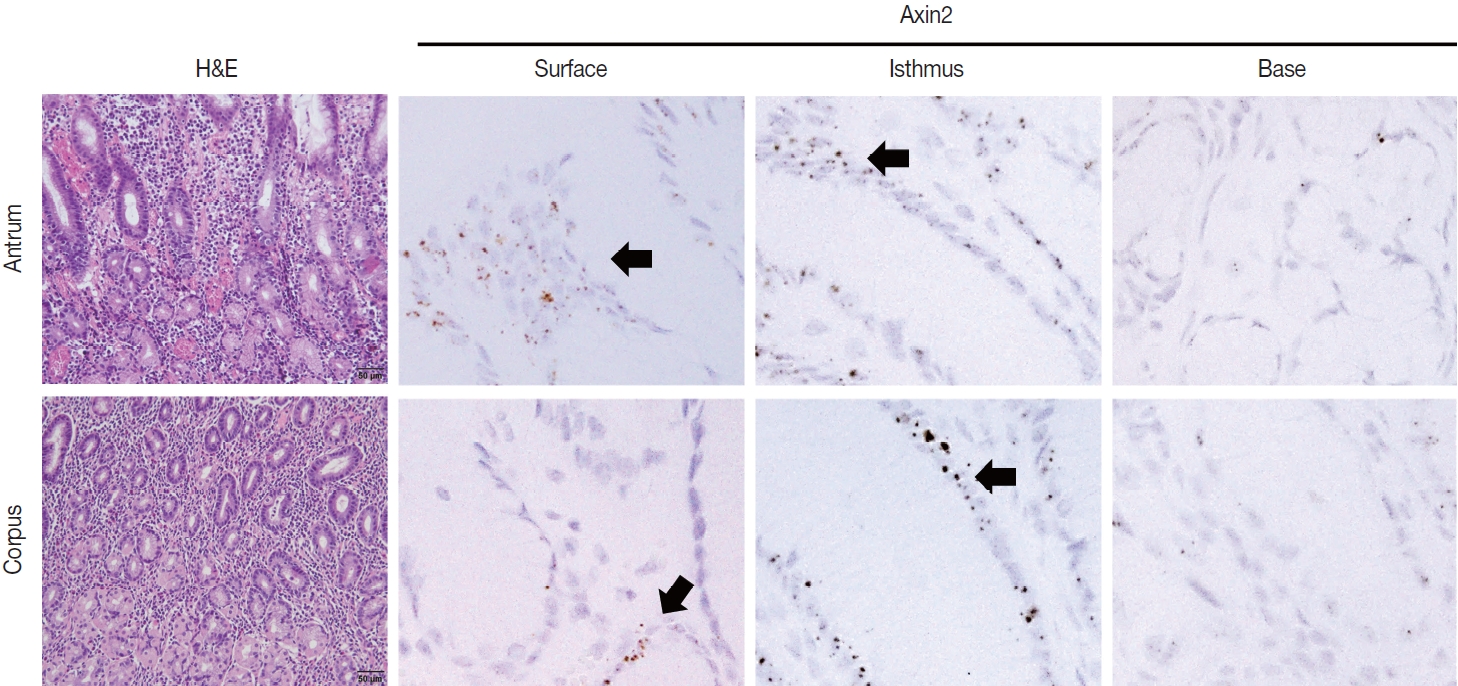

To examine Axin2 expression in the non-tumorous stomach, we performed RNA in situ hybridization for Axin2 with 12 cases of normal gastric tissues (n = 12, comprising 20 spots): including samples from normal gastric mucosa without inflammation (5 spots), gastritis cases (5 spots), and IM (10 spots). We observed a significant level of Axin2 expression in the normal stomach without inflammation. Axin2 was primarily expressed in the superficial epithelial cells and isthmus areas with an intensity level of 2 or lower (Fig. 1). In contrast, Axin2 expression was rarely observed at the gland bases. Then, we determined Axin2 expression in gastritis cases and observed a similar extent of Axin2 expression to as seen in the normal gastric mucosa (Fig. 2).

Axin2 expression in normal gastric mucosa. Normal antrum and corpus show focal Axin2 expression (intensity level 2) in the superficial and isthmic areas.

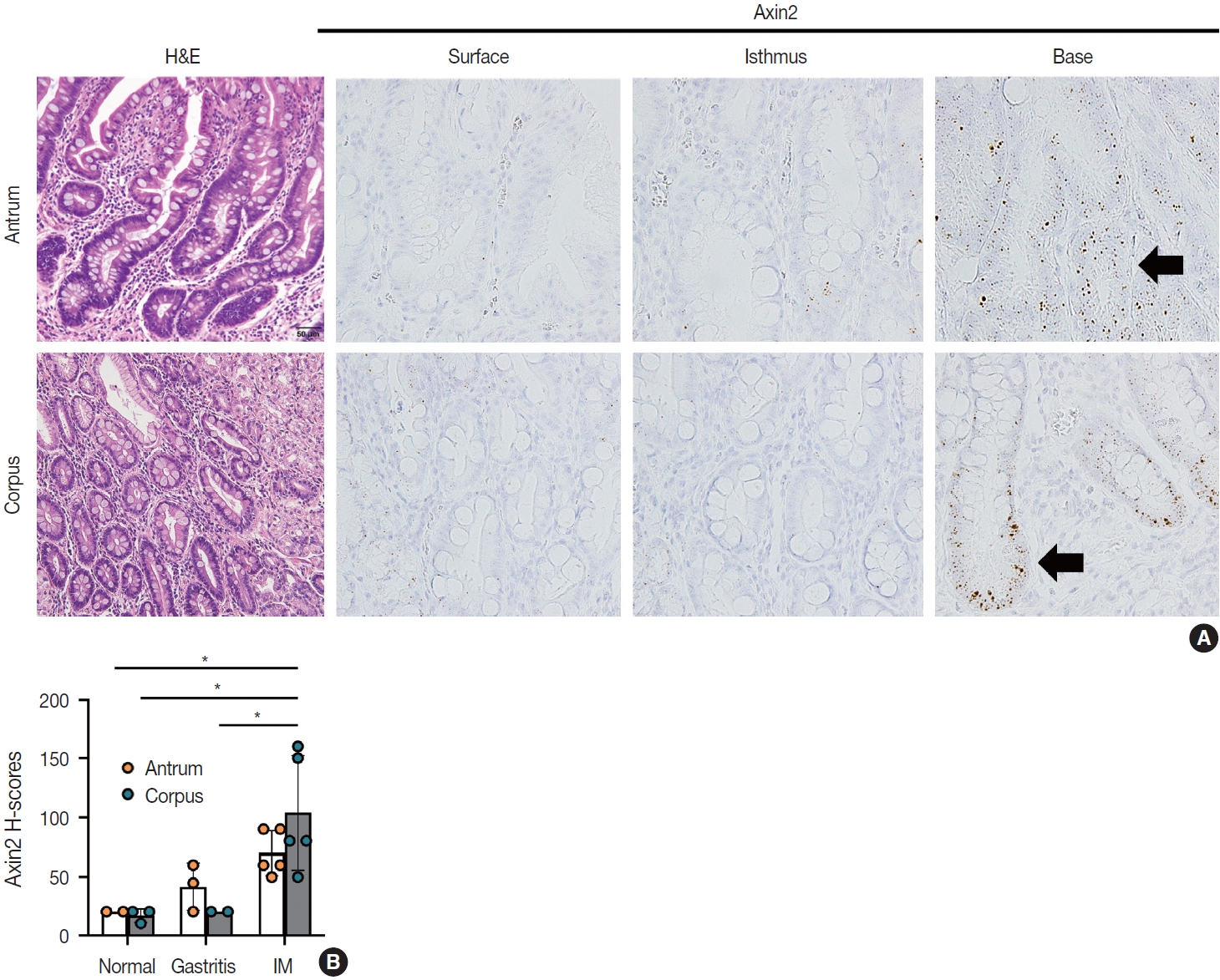

Axin2 expression in IM

IM is considered a precancerous lesion of GC. Thus, we evaluated Axin2 expression in IM and found that Axin2 expression was remarkably increased with an intensity level of 3 or higher both in the antrum and corpus. In particular, Axin2 expression was accentuated at the bases of IM glands (Fig. 3A), while the surface and isthmus regions displayed an intensity level of 2. Likewise, goblet cells in the superficial area did not exhibit Axin2 expression, whereas those at the base region displayed an intensity level of 2 to 3. We determined H-scores of Axin2 in 12 nontumorous tissue samples. Axin2 expression was significantly upregulated in IM (H-score: mean ± standard deviation [SD], 87.00 ± 38.88) compared to normal (H-score: mean ± SD, 18.00 ± 4.47) and gastritis (H-score: mean ± SD, 33.00 ± 18.57) cases (Fig. 3B). These findings suggest that Axin2 expression might be associated intestinal differentiation or indicate a development into precancerous stage.

Increased Axin2 expression in intestinal metaplasia (IM). (A) IM lesions in the antrum and corpus show enhanced Axin2 expression (intensity level 2–3) mainly at the bases. (B) A bar graph showing histo-scores (H-scores) of Axin2 in the non-cancerous stomach tissues, including normal gastric tissue, chronic gastritis, and IM cases. *p < .05.

Associations of Axin2 expression with clinicopathological features in gastric carcinomas

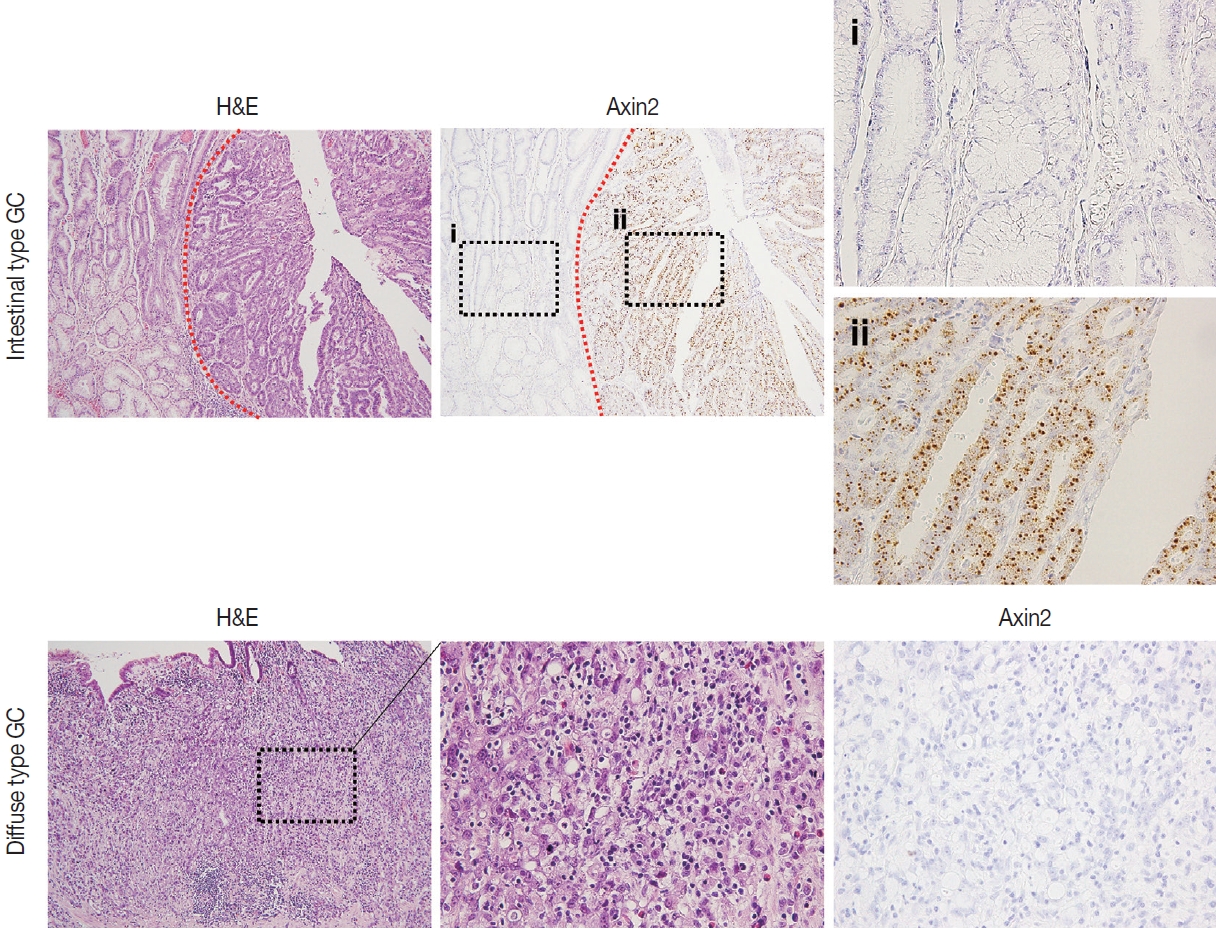

Next, we examined Axin2 expression in 56 cases of early gastric carcinomas and measured H-scores. Patient characteristics including age, gender, Lauren classification, histological differentiation, invasion depth, and lymph node metastasis is presented in Table 1. We considered Axin2 expression high when Hscores were higher than 68 based on the fact that mean value of H-score was 68. In total, 30% of GC cases showed high Axin2 expression (Table 1). No clinicopathological characteristic was found to be significantly associated with Axin2 expression (Table 1). Although it did not reach the statistical significance, high Axin2 expression was more often observed in GC patients with older age (p = .062), and intestinal-type gastric carcinomas tend to show high Axin2 expression (p = .286) (Fig. 4). Furthermore, lymph node metastasis was not observed in Axin2-high GC (p = .108).

Axin2 expression in gastric carcinomas according to Lauren classification. Representative intestinal (A) and diffuse type (B) gastric carcinomas showing high or low Axin2 expression. Red dotted lines indicate the border between normal gastric mucosa and gastric carcinoma. Black dotted boxes denote enlarged areas.

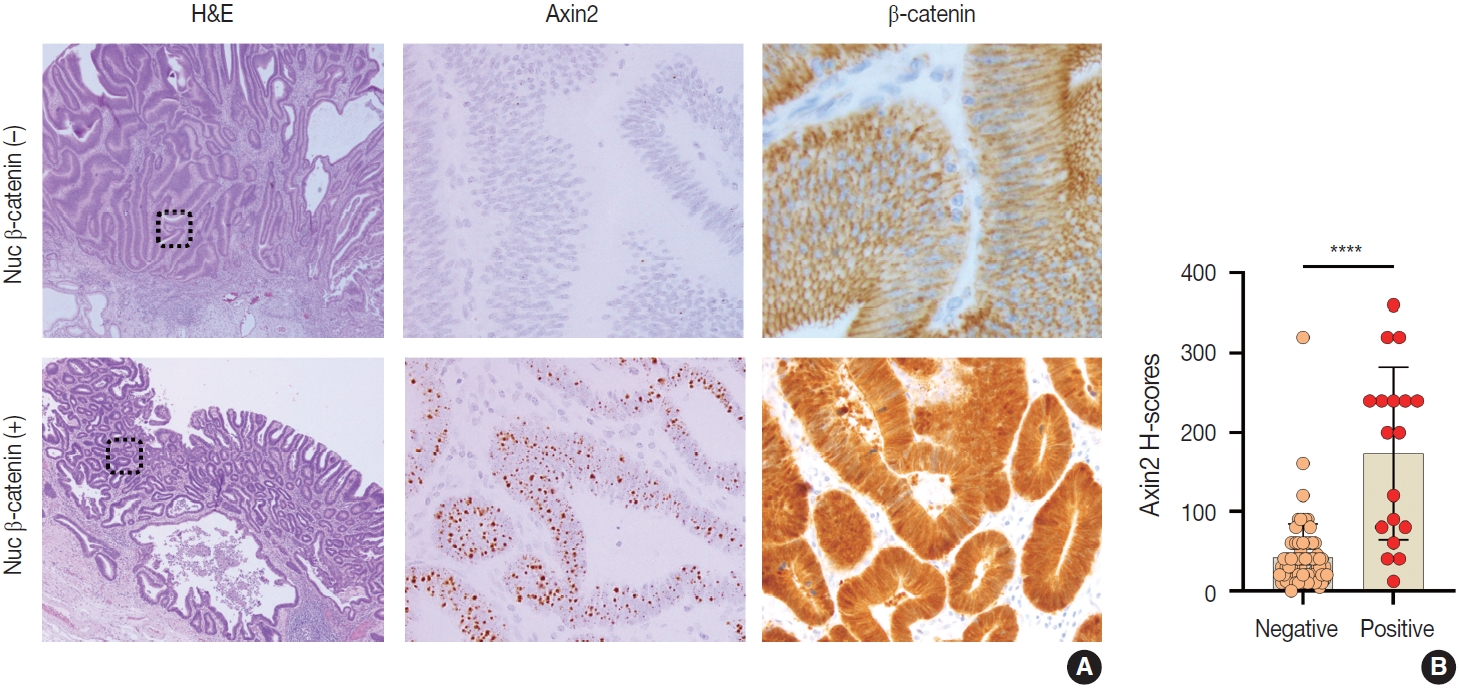

Nuclear β-catenin expression in gastric carcinomas and its correlation with Axin2

Nuclear β-catenin represents abnormal activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Since Axin2 is one of the target genes of Wnt pathway, we hypothesized that Axin2 expression might be associated with nuclear β-catenin expression. Therefore, we performed IHC for β-catenin on GC cases and found that 12 cases (21%) of GC exhibited nuclear β-catenin expression (Table 1). Notably, Axin2 expression exhibited a strong positive association with nuclear β-catenin (p < .001) (Table 1). Representative images are presented in Fig. 5A. Among 44 cases with negative nuclear β-catenin, 37 cases (84%) displayed low Axin2 H-scores (mean ± SD, 78.00 ± 77.04), while seven cases (16%) exhibited high Axin2 H-scores. Conversely, in the subset of 12 cases featuring positive nuclear β-catenin, two cases (17%) demonstrated low Axin2 H-scores, while the remaining 10 cases (83%) exhibited high Axin2 H-scores (mean ± SD, 179.40 ± 87.09). Axin2 H-scores were significantly higher in GC with nuclear β-catenin expression (Fig. 5B), clearly indicating that abnormally enhanced Wnt/b-catenin activity might be associated with elevated Axin2 expression.

Associations between Axin2 and nuclear β-catenin (nuc β-catenin) expression in gastric carcinomas. Representative cases showing low Axin2 and negative nuclear β-catenin expression (A) and high Axin2 and positive nuclear β-catenin expression (B) in gastric carcinomas. (C) A bar graph showing histo-scores (H-scores) of Axin2 in gastric carcinomas with negative nuclear β-catenin expression or positive nuclear β-catenin expression. ****p < .0001.

DISCUSSION

When comparing the expression of Axin2 among normal, gastritis, and IM, normal and gastritis samples demonstrated H-scores below the average in the surface and isthmus regions, respectively. Conversely, IM predominantly exhibited elevated H-scores, particularly at the base of glands (Fig. 5). The absence of a substantial increase in Axin2 expression in gastritis suggests that mild to moderate gastritis does not induce activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway. In contrast, Axin2 expression was significantly increased in cases of IM. We believe that this is the first study that has demonstrated the upregulation of Axin2 in IM. Considering that Axin2 is normally highly expressed in the crypt bases of normal intestines, Axin2 upregulation in IM seems to be associated with the transition into intestinal phenotype. This observation appears to align with previous research indicating that the progression of IM increases the susceptibility to dysplasia and carcinoma in the stomach [14]. However, further studies are required to fully understand the implications of Axin2 in IM, for example, whether it is involved in the progression of IM into dysplasia or gastric carcinoma. Despite the relatively limited number of IM cases in the present study, our results provided a connection between the IM and Axin2 expression.

Axin2 is a direct target gene of Wnt/β-catenin. It exerts control over the cytoplasmic levels of β-catenin by facilitating its degradation [1]. In the absence of Wnt signaling, the amino terminus of β-catenin undergoes phosphorylated by CK1 and GSK-3β, leading to its destruction through multi-protein destruction complex composed of APC, GSK-3β, Axin1, and conductin/Axin2. This process results in the proteasomal degradation of β-catenin [15,16]. In the nucleus, β-catenin bonds with TCF to activate expression of various genes including Axin2. Axin2 participates in the negative feedback regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by promoting the degradation of β-catenin [17]. Consistent with this role, Axin2 has been demonstrated to act as a tumor suppressor [16]. Carcinomas arising due to abnormalities in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway exhibit increased expression of nuclear β-catenin [18]. Therefore, we suggest that increased Axin2 expression in gastric carcinomas is likely derived from the enhanced Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Furthermore, it might be meaningful to explore the potential of high Axin2 expression as a prognostic factor for gastric car-cinoma, similar to abnormal β-catenin nuclear expression [19].

One disappointing aspect of our findings is the absence of a discernible correlation between the expression level of Axin2 and the differentiation status of gastric carcinomas. This observation implies that the differentiation of GC might be governed by mechanisms independent of abnormal activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. As previously established, well-differentiated (WD) carcinoma and poorly differentiated (PD) carcinoma follow distinct carcinogenetic pathways [20]. While WD carcinoma is primarily associated with factors such as H. pylori infection, hTERT-positive stem cell hyperplasia, and genetic instability, PD carcinoma is linked to events like chromosome 17p’s loss of heterozygosity (LOH), mutation or LOH of p53, and mutation or loss of E-cadherin [20]. Our initial hypothesis suggested that Axin2 might play a role in the differentiation process; however, our results did not yield substantial evidence to substantiate this notion.

This study has certain inherent limitations. Firstly, we did not simultaneously assess other components of the Canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. The progression of cancer cells can occur through specific proteins other than β-catenin and Axin2. Further study is required to better understand the interactions between Axin2 and other essential proteins in Wnt signaling pathway. Secondly, there exists an imbalance in the number of cancer tissues exhibiting high Axin2 expression compared to low expression. Ideally, a more balanced distribution would be desirable. However, in our experimental setup, the ratio of patients with Axin2-high GC to those with Axin2-low GC was approximately 1:2. Consequently, future experiments with a greater number of Axin2-high GC could yield results differing from those obtained in this study. Furthermore, the evaluation of Helicobacter pylori infection and the noncanonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway was not included in our study. Prior research has reported an increase in nuclear β-catenin and TCF/LEF transactivation due to H. pylori [21,22]. Hence, exploring the potential association between H. pylori infection and Axin2’s negative feedback could offer meaningful insights.

In summary, we discovered that Axin2 expression is significantly increased in IM compared to normal gastric tissue and gastritis, in line with the fact that IM is a precancerous stage for dysplasia or cancer progression. The expression level of Axin2 in GC was also associated with the nuclear expression of β-catenin, demonstrating the intimate relationship between Axin2 and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Further research is required to explore the potential of Axin2 as a prognostic marker in GC.

Notes

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Institutional Review Board of JNUH (IRB 2021-07-007) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent from the patients was exempted by IRB approval.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: DHL, IHJ, BJ. Data curation: DHL, IHJ, BJ. Formal analysis: BJ. Investigation: DHL. Supervision: BJ. Visualization: DHL. Writing—original draft: DHL. Writing—review & editing: BJ. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding to declare.