Intravascular NK/T-cell lymphoma: a case report and literature review

Article information

Abstract

Intravascular lymphoma is characterized by an exclusively intravascular distribution of tumor cells. Intravascular natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (IVNKTL) is extremely rare, highly aggressive, commonly Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive, and predominantly affects the skin and central nervous system. Here we report a case of IVNKTL diagnosed in a 67-year-old female, presenting with persistent intermittent fever and skin rashes throughout the body. Incisional biopsy of an erythematous lesion on the chest exhibited aggregation of medium to large-sized atypical lymphoid cells confined to the lumen of small vessels that were positive for CD3, granzyme B, and CD56 on immunohistochemistry and EBV-encoded RNA in situ hybridization. EBV DNA was also detected in serum after diagnosis. With a review of 26 cases of IVNKTL to date, we suggest that active biopsy based on EBV DNA detection may facilitate early diagnosis of IVNKTL.

Intravascular lymphoma (IVL) is a rare extranodal lymphoma characterized by selective proliferation of lymphoma cells within the lumina of small blood vessels. IVL of the B-cell lineage is more common, and intravascular B-cell lymphoma was classified as a distinct disease entity in the revised 4th edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of hematolymphoid tumors, while intravascular natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma (IVNKTL) has not, and this has remained the same in the 5th edition [1,2]. IVNKTL is extremely rare and has been described as a rare extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma (mass-forming) in the WHO classification. However, it differs from non-mass lesions based on distinct disease behavior. IVNKTL is mostly Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive, highly aggressive, and predominantly affects the skin and central nervous system [3]. Since its pathological characteristics are still unclear, it was described as an aggressive NK-cell leukemia rather than an extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma in the 5th WHO classification. However, further studies are required to determine where it fits best [2].

To the best of our knowledge, 26 cases of IVNKTL with sufficient immunohistochemical and clonality data have been reported thus far, with two cases from Korea [4-23]. Herein, we report another case of IVNKTL with confirmed serum EBV DNA and review previously reported cases from a diagnostic perspective.

CASE REPORT

A 67-year-old woman with a history of asthma (adequately treated) was admitted with an intermittent night fever (39°C) lasting 1 month and general weakness that persisted after antibiotic treatment at a local hospital. Other vital signs were stable and there were no symptoms or signs other than fever, erythematous skin rash on the chest, and general weakness. Laboratory tests revealed slightly low white blood cell count, 3,090/mm3 (4000–10,000/mm3), and increased aspartate transaminase level of 99 U/L (0–37 U/L), alanine transaminase level of 42 U/L (0– 41 U/L), and lactate dehydrogenase level of 2,600 U/L (135– 225 U/L). Peripheral blood smear findings were normal. Immunological tests for antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factors were negative. Blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and urine cul-tures also yielded negative results. Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed a focal consolidative lesion in the right lower lobe and bronchial wall thickening in both lungs. Slightly enlarged lymph nodes were found in the mediastinum and both hilar regions. Positron emission tomography showed multiple focal hot uptake lesions in bones, suggesting the differential diagnosis of multiple myeloma. However, a bone marrow biopsy and protein electrophoresis revealed no evidence of multiple myeloma or other malignancies. Abdominal and brain CT showed no remarkable findings. There was no history or evidence of hemophagocytic syndrome. The origin of the fever remained unclear. Given the recurrent fever, skin rash, and lymphadenopathy, adult-onset Still disease was suspected, and high-dose prednisolone was prescribed. After treatment, the fever subsided, but the skin rash showed little improvement. The patient developed a fever again, accompanied by multiple erythematous skin lesions all over her body. Her mental status decreased, and she underwent episodes of seizure. Brain CT and magnetic resonance imaging scans showed no specific findings. An incisional skin biopsy of the anterior chest was performed.

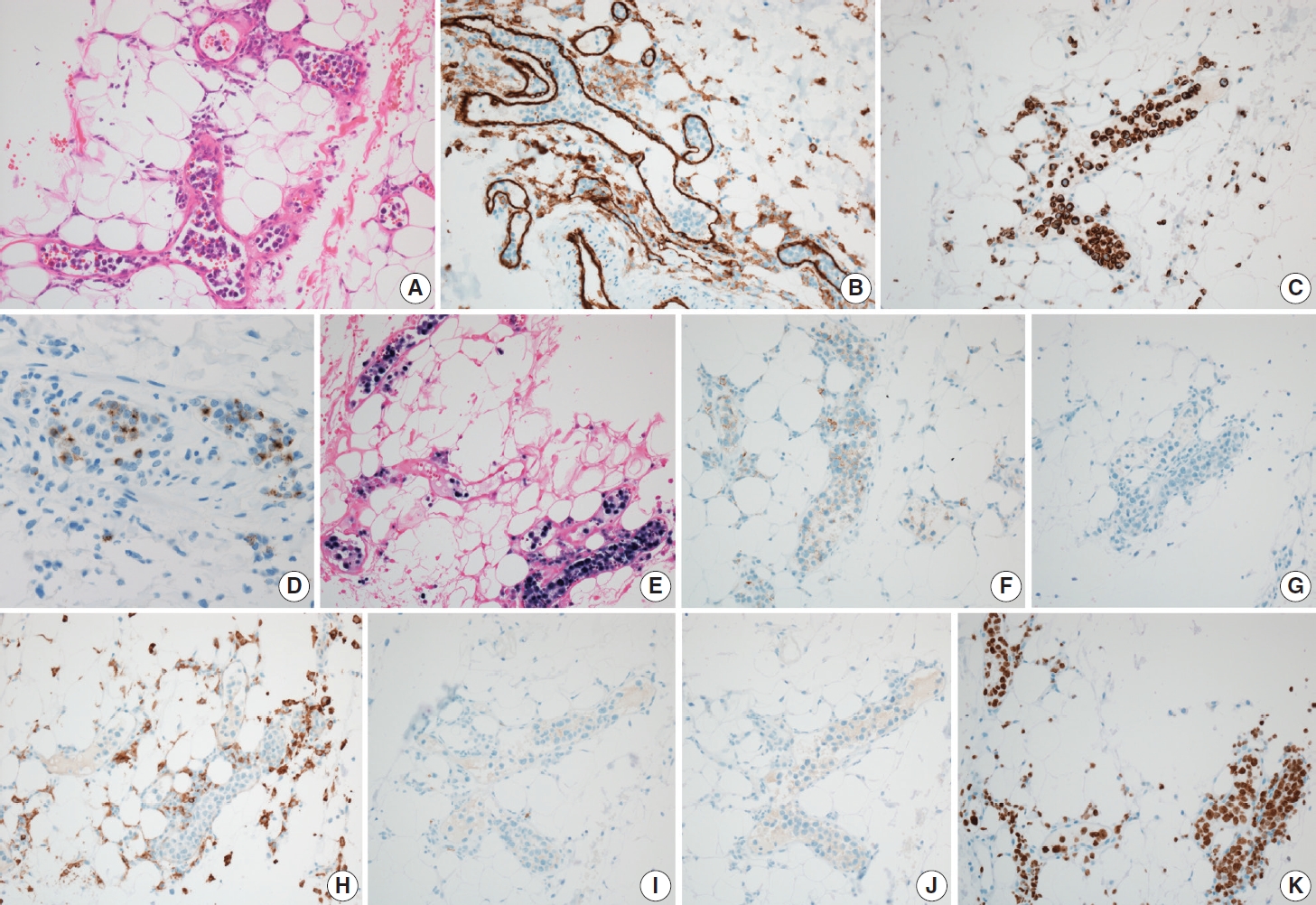

Microscopic examination of skin specimen revealed mildly dilated capillaries in the dermis and superficial subcutaneous fat. Atypical lymphoid cells were confined to the lumen of the small blood vessels. The intravascular atypical cells were medium to large in size compared to normal lymphocytes and were poorly cohesive. The atypical cells had large, irregular nuclei and scanty cytoplasm (Fig. 1A). Occasional mitoses were observed. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for CD31 highlighted the vasculature, and the intravascular presence of atypical cells was confirmed (Fig. 1B). Atypical cells were positive for CD3 (Fig. 1C), granzyme B (Fig. 1D), and EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) in situ hybridization (Fig. 1E). CD56 was weakly positive in the atypical cells (Fig. 1F). CD20, CD4, CD8, and CD30 expression were negative (Fig. 1G–J), and the Ki-67 proliferation index was >90% (Fig. 1K). A T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangement test did not show monoclonal T-cell proliferation. In conclusion, the patient was diagnosed with cutaneous intravascular EBV-positive NK/T-cell lymphoma. After diagnosis, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detected EBV DNA (445,000 copies/mL) in serum. The patient’s clinical condition deteriorated with acute respiratory failure, and her mental status did not improve. She and her family opted for hospice care and no further pathological examination was done, but the progression of symptoms suggested that multiorgan failure and brain involvement had occurred. The patient expired 18 days after diagnosis.

Microscopic findings of cutaneous intravascular natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Medium-sized atypical lymphoid cells can be seen in subcutaneous vessels (A). CD31 highlights vasculature (B), and atypical cells are positive for CD3 (C), granzyme B (D), and Epstein-Barr virus– encoded RNA in situ hybridization (E). CD56 shows weak positivity in atypical cells (F). CD20 (G), CD4 (H), CD8 (I), and CD30 (J) are negative. Ki-67 index is more than 90% (K).

DISCUSSION

IVNKTL is an extremely rare, highly aggressive lymphoma that predominantly involves the skin and central nervous system. Histological diagnosis is essential. Twenty-seven cases of IVNKTL, including the present case, with sufficient immunohistochemical and clonality data, have been reported (Table 1). The patients included 13 men and 14 women aged 18–87 years. The clinical presentation varied, including skin rash, neurologic symptoms, fever, cytopenia, weight loss, and malaise. Most patients had skin lesions (23/27, 85.2%, skin lesion only in 11 patients). Central nervous system involvement was found in 10 patients (10/27, 37.0%). Most of tested cases showed EBER positivity (22/26, 84.6%). Seven cases with clonality data showed the presence of monoclonal proliferation (7/22, 31.8%).

A skin biopsy is the easiest and most effective way to diagnose IVNKTL; however, it is challenging in patients without obvious skin lesions. Of the four patients without skin lesions, two presented with neurological symptoms and were diagnosed by brain biopsy (cases No. 23 and 26), and the other two were confirmed on autopsy (cases No. 3 and 25). Brain biopsy is more burdensome than skin biopsy. In each case, brain biopsy was performed after neurological symptoms worsened, and EBV DNA was detected in the CSF. The other two patients showed various symptoms and signs, including pancytopenia at presentation, and were diagnosed by bone marrow biopsy and autopsy. Autopsies of the last two patients revealed multiorgan involvement of IVNKTL, including the brain, kidneys, and bone marrow.

Bone marrow involvement was uncommon (4/19, 21.1%) and seemed to be associated with poor prognosis. In the case reported by Gebauer et al. [13] (case no. 14), bone marrow biopsy revealed dense medullary infiltration of IVNKTL, constituting approximately 40% of the overall cellularity. However, bone marrow biopsies showed only subtle sinusoidal lymphomatous infiltration in the other two cases (cases Nos. 3 and 25). The remaining case exhibited no evidence of neoplastic infiltration in morphological and IHC analyses of the bone marrow biopsy, and only TCR gene rearrangement test of the bone marrow aspirate confirmed clonality (case No. 23). Although bone marrow involvement may be uncommon, it can also easily be missed. Meanwhile, patients with bone marrow involvement showed shorter survival (<1 month) after confirmation of bone marrow involvement. Bone marrow involvement may indicate rapid disease progression; however, further evaluation is needed.

Most reports did not mention EBV DNA PCR testing (24/27, 88.9%). In three recent cases, EBV DNA PCR of pleural effusion, lung tissue (case No. 25), CSF (case No. 26), and blood (present case) was positive. Serum EBV DNA load has been suggested as a biomarker in EBV-associated cancers such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and EBV-positive Hodgkin lymphoma [24]. IVNKTL may also present with a high serum EBV DNA load. Since procedures for histopathological examination (e.g., brain biopsy) are invasive, detection of serum EBV DNA could provide a supportive basis for conducting further work-up for diagnosis, especially in patients without apparent skin lesions.

In conclusion, we reported a case of IVNKTL in which serum EBV DNA was detected. An active skin biopsy or other invasive biopsy based on EBV DNA detection may facilitate early diagnosis of IVNKTL.

Notes

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gyeongsang National University Hospital, and the need for informed consent was waived (IRB No. GNUH 2023-07-033).

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: JWY. Data Curation: JMN, WJ, JWY. Investigation: JMN, WJ, JWY. Resources: MK, YHC, JSL. Supervision: YHC, JWY. Visualization: JMN, JWY. Writing—original draft preparation: JMN, JWY. Writing—review & editing: JMN, DHS, JWY. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Dong Hoon Shin (Pusan National University Yang-San Hospital) for assistance in performing immunohistochemistry stain for granzyme B.