Histopathological characteristics of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–associated encephalitis and colitis in chronic active EBV infection

Article information

Abstract

Chronic active Epstein-Barr virus (CAEBV) can induce complications in various organs, including the brain and gastrointestinal tract. A 3-year-old boy was referred to the hospital with a history of fever and seizures for 15 days. A diagnosis of encephalitis based on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging findings and clinical correlation was made. Laboratory tests showed positive serology for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and negative for Rotavirus antigen and IgG and IgM antibodies for cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella zoster virus, respectively. Abdominal CT showed diffuse wall thickening with fluid distension of small bowel loops, lower abdomen wall thickening, and a small amount of ascites. The biopsy demonstrated positive Epstein-Barr encoding region in situ hybridization in cells within the crypts and lamina propria. The patient was managed with steroids and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). This case showed histopathological characteristics of concurrent EBV-associated encephalitis and colitis in CAEBV infection. The three-step strategy of immunosuppressive therapy, chemotherapy, and allogeneic HSCT should be always be considered for prevention of disease progression.

INTRODUCTION

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a double-stranded DNA virus categorized within the Herpesviridae family, causes a ubiquitous infection in more than 90% of the world’s population [1,2]. EBV is usually acquired during childhood or adolescence and then establishes a permanent latent infection in B lymphocytes in immunocompetent patients [3-5]. Chronic active EBV (CAEBV) infection is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by persistent infectious mononucleosis-like symptoms for more than 3 months, increased EBV DNA (>102.5 copies/mg) in peripheral blood, and organ involvement in an immunocompetent patient [6-8]. Various organs can be affected in CAEBV infection and they show a spectrum of manifestations. The ill-defined, diverse clinicopathological characteristics of CAEBV infection often delay the diagnosis and treatment [1,9,10]. In this study, we report a 3-year-old patient with CAEBV infection, who was confirmed to have both EBV encephalitis and EBV colitis through pathological examination. The diagnosis of EBV encephalitis and EBV colitis can be a challenge in pathological practice because of the deceptive morphologies. Using microscopic examination and in situ hybridization technique, we diagnosed EBV infection in both the brain and colon tissue, resulting in successful diagnosis and treatment.

CASE REPORT

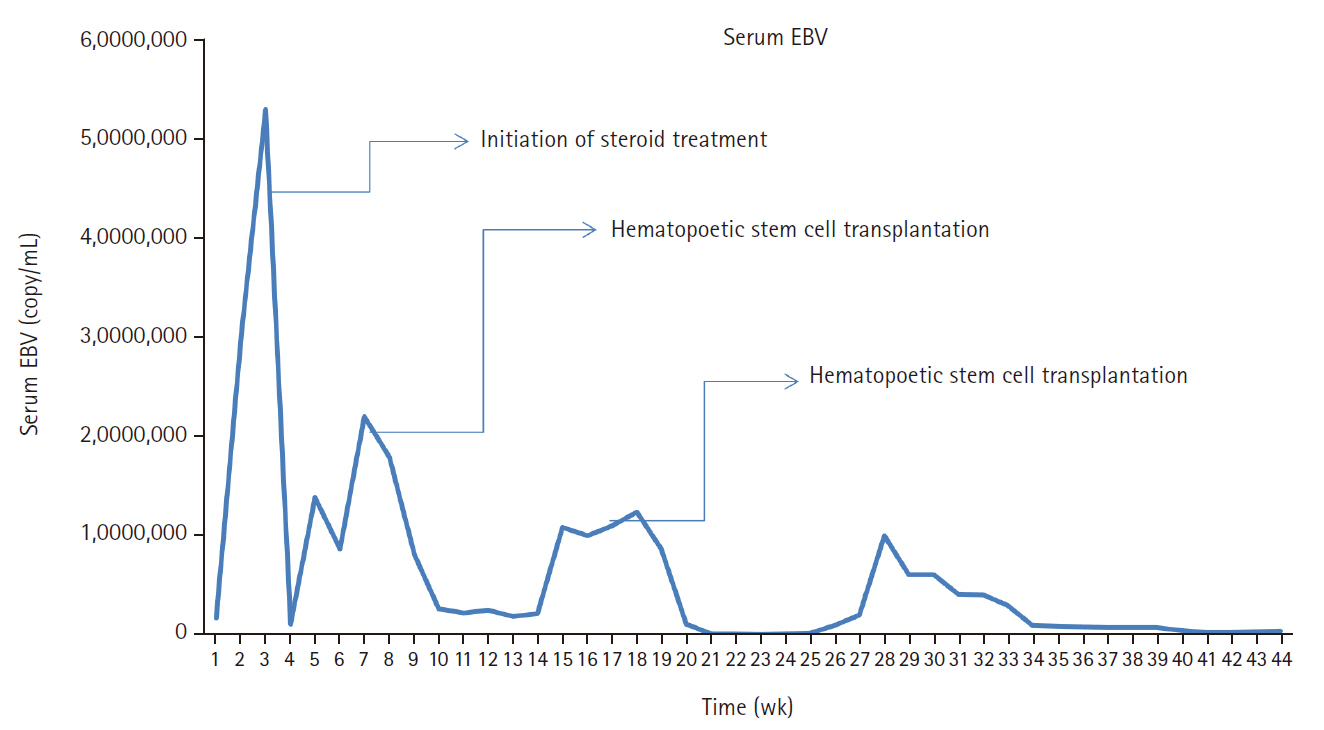

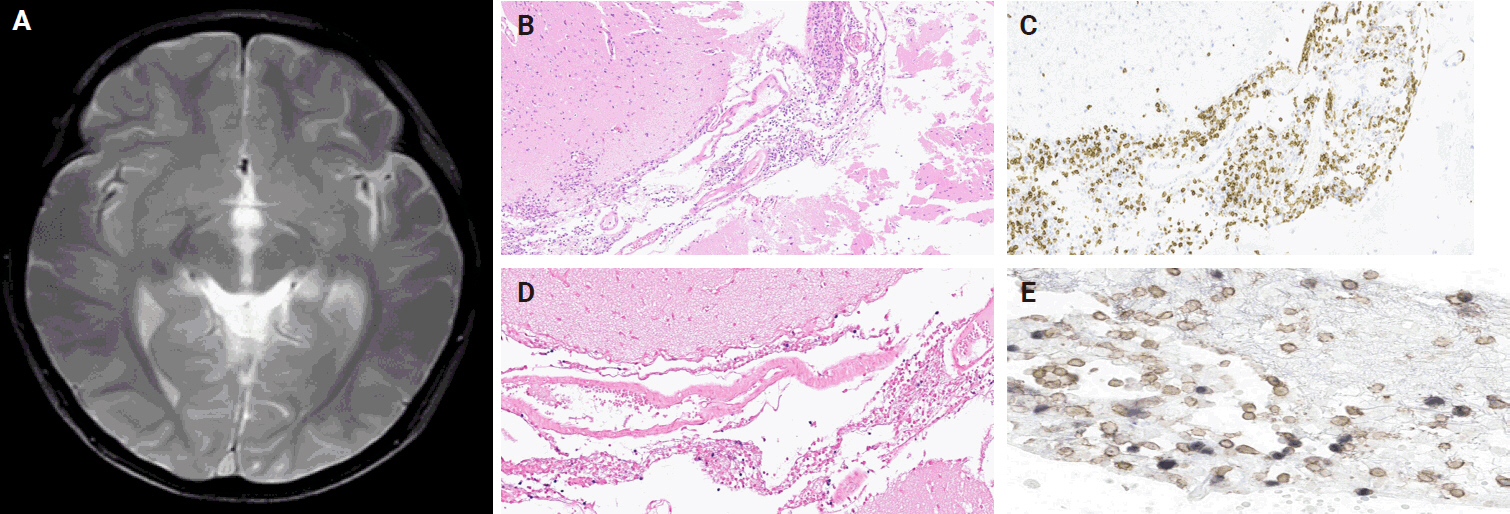

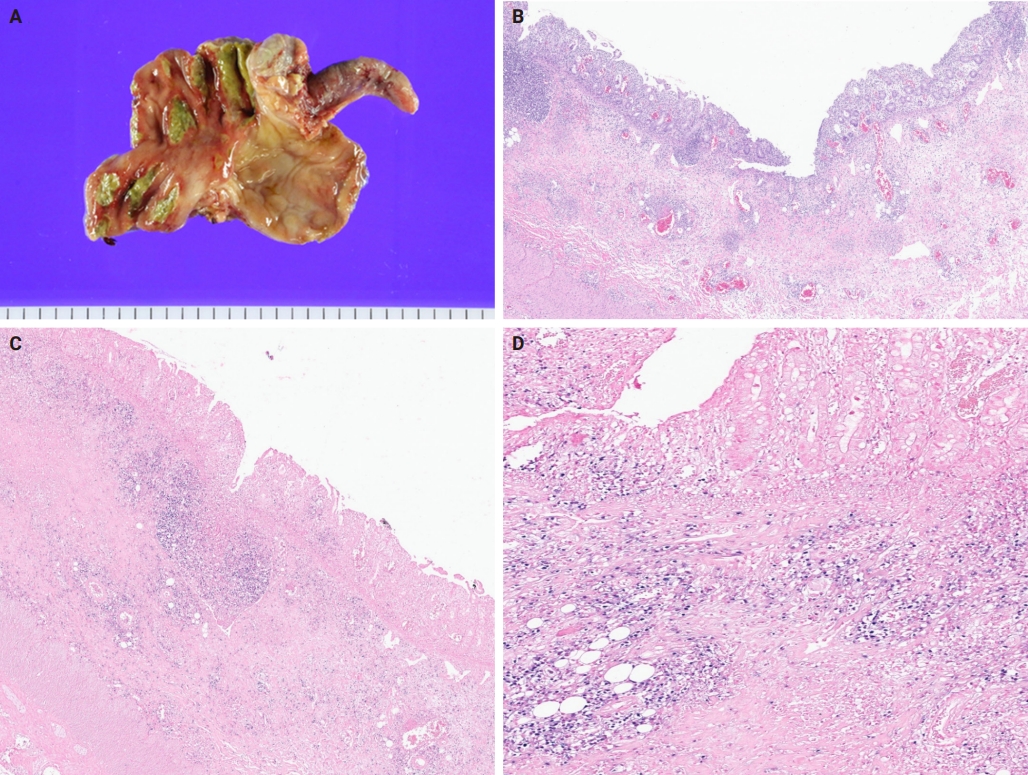

A 3-year-old boy was admitted to the Severance Hospital (Seoul, Korea) with a history of fever and seizures for 15 days. The boy did not have any history of recurrent infections or family history of immune disease. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed swelling in the basal ganglia, thalamus, midbrain, pons, cerebellum, and left hypothalamus (Fig. 1A). The initial EBV level was elevated to 1,685,506 U/mL in the serum and 103,285 U/mL in the cerebrospinal fluid. In serology, anti–viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgM was undetected while anti-VCA IgG was positive which indicated chronic response to EBV. Although the patient was managed empirically with steroids, his mental status remained unstable. To confirm the diagnosis, brain biopsy was performed. The brain tissue sections showed focal perivascular and subarachnoid lymphocyte infiltration and focal microglial cell proliferation (Fig. 1B). However, CD3-positive T lymphocytes infiltrated the perivascular area (Fig. 1C) and these cells were positive to EBV in situ hybridization (Fig. 1D). Further testing revealed that CD3-positive cells expressed CD8 (Fig. 1E), but not CD4. Moreover, molecular analysis showed no evidence of T-cell receptor (TCR) beta or TCR gamma gene rearrangement. A week later, the patient developed perianal ulceration, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Abdominal CT showed diffuse wall thickening and distension in the small bowel loops indicating high risk of perforation. The patient underwent ileocecectomy (Fig. 2A). The resected colon showed dense infiltration of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells in the lamina propria and widespread neutrophilic cryptitis, crypt abscess, and distortion. The lymphocytes showed minimal atypia. Multifocal submucosal edema with serositis was prominent (Fig. 2B). Diagnosis of EBV-associated colitis was made based on Epstein-Barr encoding region (EBER) in situ hybridization of positive CD3 T lymphocytes that infiltrated the mucosa, submucosa, and intestinal walls (Fig. 2C, D). Immunohistochemical staining for CD56 showed a few scattered natural killer (NK) cells. The diagnosis of CAEBV also befits the patient. Germline testing using next-generation sequencing analysis revealed no pathogenic gene mutations associated with immune dysregulation. The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing results were as follows: HLA-A*02:06/02:06, -B*15:18/51:01, -C*08:01/14:02, -DRB1*04:05/14:05, -DQA1*01:04/03:03, -DQB1*04:01/05:03, -DPA1*01:03/02:02, and -DPB1*02:01/05:01. Full matched allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) was performed 6 months after the initial diagnosis. EBV level decreased to 34,262 copies/mL in serum 12 months after treatment (Fig. 3).

(A) Magnetic resonance imaging showing swollen and multifocal T2 high signal intensity with swelling of the basal ganglia, thalamus, midbrain, pons, cerebellum, and left hypothalamus. (B) Brain tissue sections showing focal perivascular and subarachnoid lymphocyte infiltration and focal microglial cell proliferation. (C) CD3-positive T- lymphocytes infiltrating the perivascular area. (D, E) In situ hybridization of Epstein-Barr encoding region and CD8-positive Epstein-Barr virus double-staining cells from the brain tissue.

(A) Gross appearance of the ileocecectomy specimen with appendix attached, the mucosa surface showing multiple ulcerative lesions in the cecum. (B) The ileocecectomy specimen demonstrating infiltration of the lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells in the lamina and widespread neutrophilic cryptitis, crypt abscess, and distortion. (C, D) CD3-positive Epstein-Barr encoding region (EBER) in situ hybridization cells from the colon tissue (EBER antibody staining).

DISCUSSION

We herein report a patient with CAEBV infection showing both EBV encephalitis and colitis. It is an infection induced by infiltration of EBV-infected lymphocytes into the affected tissues [11,12]. EBV infects NK and T cells in CAEBV; T-cell CAEBV is further classified into CD4- and CD8-positive types [12,13].

Comprehensive assessment of multiple organs with high suspicion and correct recognition of EBV-associated histopathological features are important for the diagnosis of CAEBV infection [14]. It was difficult to diagnose EBV encephalitis and colitis in our patient owing to the subtle and deceptive morphologies. A brain biopsy performed after steroid treatment demonstrated mild lymphocytic infiltration and subtle microglial proliferation. The colon showed inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)–like microscopic changes, including marked glandular distortion and transmural chronic inflammation with cryptitis and crypt abscess. The detection of EBV in tissue samples using in situ hybridization demonstrated an EBV-induced pathological process, highlighting the critical role of EBV assay in the diagnosis of CAEBV infection [4].

EBV can lead to various central nervous system complications [15]. Some authors have suggested that there has been an increase in the occurrence of neurological complications of EBV infection [16,17]. A study examining pediatric EBV-associated encephalitis found that EBV infection was present in 9.7% of the children hospitalized with neurological complications [18]. EBV encephalitis is rare in children but can have severe neurological complications; usually, the positive MRI findings occur in the brain stem, basal ganglia, cerebellum, and thalamus [19-21]. This was somewhat similar to MRI findings of the present case that showed hyperintense T2 lesion in the thalamus, basal ganglia, and brain stem.

EBV encephalitis can show various clinical and histological characteristics [16,22]. Establishing a diagnosis of EBV encephalitis is difficult; consequently, molecular, serological, and imaging techniques should be used when investigating children with encephalitis [15]. Biopsy is important to confirm general pediatric encephalitis because it may reveal the underlying infective process, chronic inflammatory change, or neoplastic disease [23]. Diagnosing EBV encephalitis requires demonstration of EBV-infected cells. Our case showed EBV-infected T lymphocytes infiltrating the perivascular area; this is consistent with the previous reports [16,22,24]. The EBV-infected T lymphocytes in our case were CD8-positive, thereby confirming EBV encephalitis involving CD8-positive T lymphocytes. Another study conducted on EBV encephalitis reported features of cortical infiltration of T lymphocytes with perivascular and perineuronal clusters, while the B lymphocytes were frequently seen in the perivascular cuffs [25]. The prognosis associated with EBV encephalitis is controversial. Some reports have suggested it to be a relatively benign, self-limited disease with an almost full recovery; however, others have documented the occurrence of various neurologic sequelae in a substantial number of cases [15,18,26].

Gastrointestinal involvement is very rare and few cases of immunocompetent hosts have been reported [27-29]. Among these, the lymphoid cells that were involved were of the B-cell lineage. However, our case had involvement of the T-cell lineage. EBV colitis is rare in children, and few cases have been reported [30]. EBV colitis is difficult to differentiate from IBD owing to overlapping symptoms and endoscopic findings, and discerning whether the severity of symptoms is attributable to CAEBV or the exacerbation of IBD is challenging, thereby making diagnosis of EBV colitis and IBD difficult [9,31,32]. Our case demonstrated findings that were consistent with the pathological findings observed by other authors in their studies [9,33,34]. Despite the similarity between IBD and EBV colitis, it was noted that atypical infiltrates were more frequently observed in patients with EBV positivity. Consequently, every patient with IBD should undergo the EBV test [35]. Although further studies are warranted to clarify the role of EBV in inflammatory gut disorders, it was proposed that EBV may induce immune alterations in the colon, thereby aiding the pathogenesis of EBV colitis [36]. The molecular detection of EBV-encoded RNA transcripts by in situ hybridization remains the gold standard in the identification of EBV in biopsies [35].

Our patient’s viral load was initially high on admission, after the initiation of steroids and immunosuppressive agents; it reduced gradually with significant improvement after HSCT. The effective treatment strategy for eradicating EBV-infected Tor NK-positive cells is HSCT, if initiated before deterioration of the patient’s condition. HSCT is, by far, considered the most effective treatment for CAEBV by revitalizing the hematopoietic system. However, because not all patients with CAEBV may undergo HSCT, immunosuppression and chemotherapy can also be considered with or without HSCT [37]. Although the outcome of patients with active disease accompanied by fever, liver dysfunction among others may be worse [1,38]. Studies have proved that manifestation of signs and symptoms is subject to the host immune responses [9,39]. Usually, patients with EBV infection have serious clinical abnormalities that may persist for 6 months or more with high antibody titers against EBV but not against EBV nuclear antigen [9,39]. Thus, multiple organ involvement in CAEBV infection often results in poor prognosis [14,40]. The present case may be slightly different owing to early recognition; awareness of CAEBV, especially regarding the histological changes, EBER, and EBV DNA, are crucial for patients with EBV, similar to what was observed in another study [34]. CAEBV disease and post-HSCT lymphoproliferative disorders share similarities. However, although both post-HSCT posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) and CAEBV disease involve EBV reactivation and immune dysfunction, distinct differences exist between conditions [3,6]. PTLD is predominantly of B-cell origin, compared to CAEBV being of T-cell origin. Although monomorphic PTLD of T-cell origin exist, it is typically EBV-negative [41].

Several genetic factors of CAEBV have been found to increase genetic susceptibility of the hosts. For example, candidate gene studies of transplant HLA have reported that transplant recipients have haplotypes, such as HLA-A26 and B36, that are associated with a higher risk of developing EBV-positive B-cell origin PTLD [42]. The HLA result of our patient indicated no increased risk to CAEBV disease.

This case showed histopathological characteristics of concurrent EBV-associated encephalitis and colitis in CAEBV infection. CAEBV is an extremely rare and severe complication that can arise from EBV infection. It is a life-threatening medical condition that is more likely to occur as a result of primary infection, reactivation, and immunosuppression. Histopathological features will help the discrimination, serum EBV DNA and in situ hybridization for EBV-encoded RNA are recommended to exclude. This condition is more likely to pose treatment challenges, especially when the treatment is initiated at a late stage. HSCT should be considered a crucial therapeutic option for preventing the progression of disease.

Notes

Ethics Statement

All procedures performed in the current study were approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Severance Hospital (reference # 4-2024-0533 dated 19th June 2024) in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. Patient consent waiver was obtained for this study.

Availability of Data and Material

All relevant data and information pertaining to the patient presented in this case report are included in the manuscript.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: MJ. Data curation: BKA, MJ. Formal analysis: SOY, SHK, MJ. Funding acquisition: MJ. Investigation: BKA, MJ. Methodology: MJ. Project administration: MJ. Resources: SOY, SHK, MJ. Software: BKA. Supervision: JJY, MJ. Validation: MJ. Visualization: BKA. Writing—original draft: BKA, MJ. Writing—review & editing: all authors. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

S.H.K., a contributing editor of the Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00341570).