ThinPrep Cytological Findings of Desmoplastic Small Round Cell Tumor with Extensive Glandular Differentiation: A Case Study

Article information

Abstract

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is a rare and highly aggressive neoplasm. The cytological diagnosis of this tumor has only been reported in a few cases. In most of these cases, the diagnosis was made using fine-needle aspiration cytology. Most DSRCTs resemble disseminated carcinomatoses in their clinical manifestation as well as cytomorphologically, even in young-adult patients. These authors report a case of using peritoneal-washing and pleural-effusion ThinPrep cytology to diagnose DSRCT, with extensive glandular differentiation and mucin vacuoles. We found that fibrillary stromal fragment, clinical setting, and adjunctive immunocytochemical staining were most helpful for avoiding misdiagnosis.

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is a rare and highly aggressive neoplasm.1 The cytological diagnosis of this tumor has only ocurred in a few cases, and most of these cases were based on fine-needle aspiration cytology.2-5 Presented herein is a case of cytological finding of DSRCT with extensive glandular differentiation using peritoneal-washing and pleural-effusion ThinPrep.

CASE REPORT

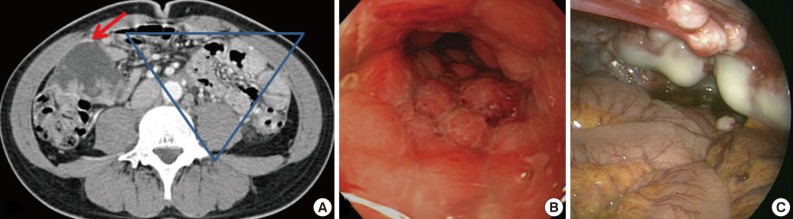

A 31-year-old man was admitted for constipation and abdominal pain that had persisted for a month. The patient was transferred for an abdominal mass on an abdominal sonogram at local clinic. Physical examination revealed a fist-sized mass on the right lower quadrant of abdomen. The initial abdominopelvic computer-tomography images showed a 5.5 cm-sized mass at the right lower quadrant with surrounding seeding nodules and mesenteric lymphadenopathy, suggesting carcinomatosis (Fig. 1A). The colonoscopy revealed a diffuse luminal narrowing due to the extrinsic masses (Fig. 1B). The laparoscopic finding showed multiple disseminated, variable-sized, firm, whitish masses or plaques on the hepatic capsule and the serosal surface of the colon (Fig. 1C).

(A) The abdomino-pelvic computer-tomography image discloses a 5.5 cm-sized mass at the right lower quadrant abdominal cavity (red arrow) and seeding nodules and mesenteric lymphadenopathy (gathered in blue inverted triangle). (B) The colonoscopic findings are compatible with extrinsic masses. The mucosa is intact. (C) The laparoscopic findings disclose multiple disseminated, variable sized whitish firm masses.

Cytological findings

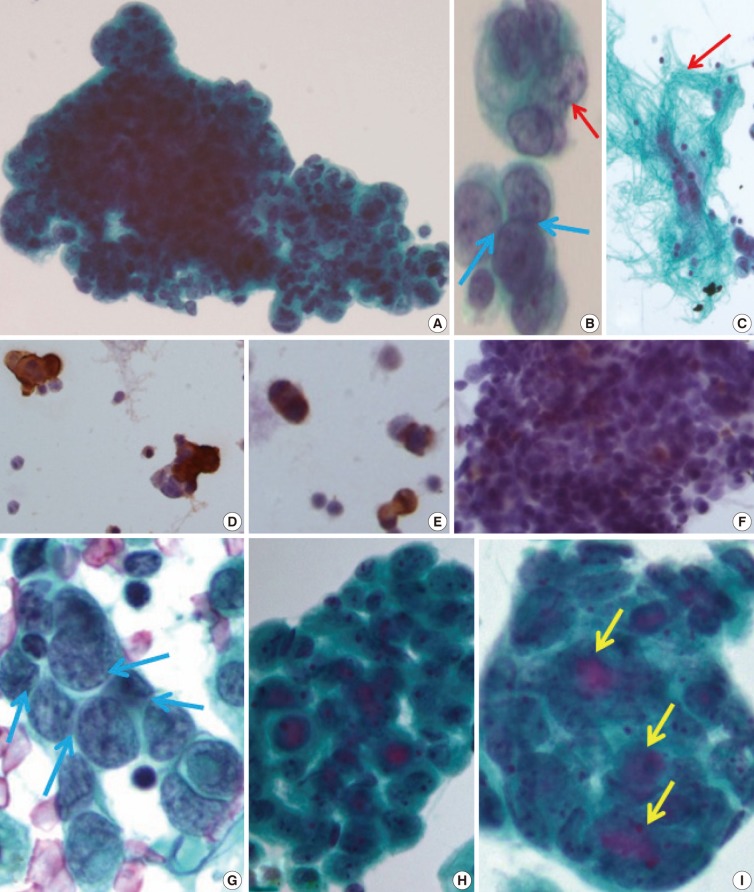

The initial peritoneal-washing fluid (ThinPrep) diagnosed the tumors as "adenocarcinoma" because the clusters of tumor cells revealed finger-like buddings (Fig. 2A). The high power field disclosed common outer-cell borders, intracytoplasmic vacuoles, convoluted nuclei, and relatively large prominent nucleoli. However, retrospective cytological review of the distinct nuclear moldings that were also identified, favored the diagnosis of small round cell tumors (Fig. 2B). There were a few fragments of fibrillary stroma (Fig. 2C). The immunocytochemical stainings were positive for vimentin (Fig. 2D), pancytokeratin (panCK) (Fig. 2E), and vaguely positive for desmin (Fig. 2F).

(A) The clusters of tumor cells are arranged in finger-like budding with common outer cell borders. (B) The tumor cells show intra-cytoplasmic vacuoles, convoluted nuclei (red arrow), and relatively prominent nucleoli, with a few foci of nuclear molding (blue arrows). (C) Thin-Prep cytology of peritoneal washing shows a few fragments of fibrillary stroma (red arrow). (D-F) Immunocytochemistry reveals a positive reaction to vimentin (D), pancytokeratin (E), and weak positive reaction to desmin (F). (G) The conventional smear of pleural effusion fluid shows clusters of angulated nuclei and distinct nuclear moldings (blue arrows). (H, I) The ThinPrep cytology of pleural effusion shows rounded clusters with a three-dimensional structures (H), with extracellular mucinous content (I, yellow arrows), and more glandular differentiation.

After eight months, a malignant pleural-effusion was detected. Conventional fluid cytology showed cytological features similar to those seen from the peritoneal washing, but angulated nuclei with distinct nuclear moldings were also present (Fig. 2G). In ThinPrep findings, the clusters were more rounded, with three-dimensional structures, and even extracellular mucin content, very similar to adenocarcinoma (Fig. 2H, I).

Histologic findings

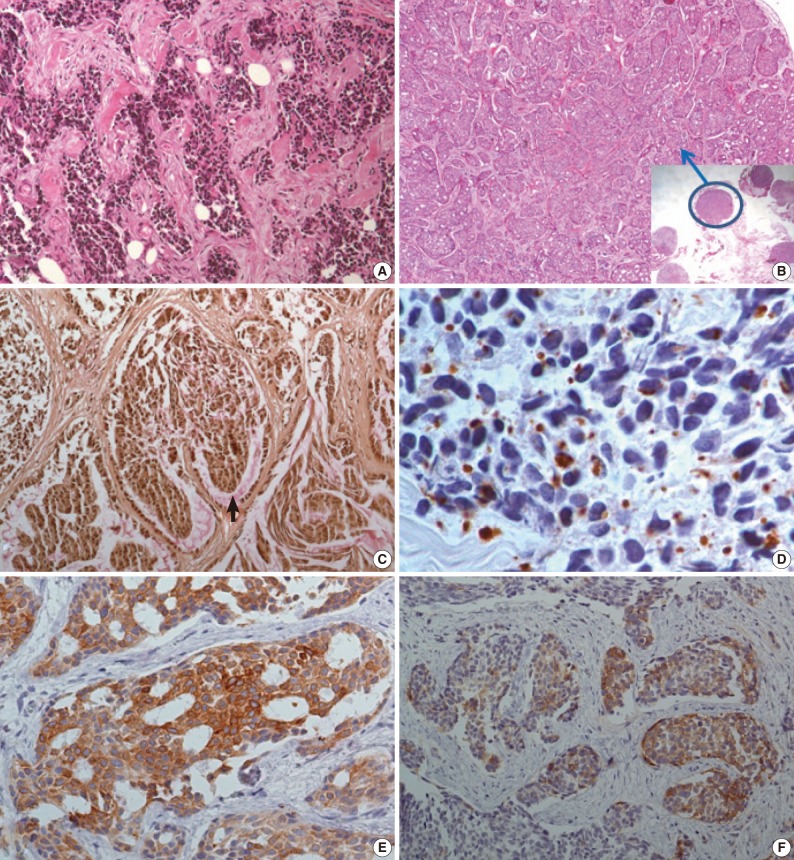

The initial laparoscopic biopsy showed typical findings of DSRCT, desmoplastic stroma, and variable-sized nests of small round cells (Fig. 3A). Four months later, a second biopsy specimen was obtained during T-loop colostomy for a marked-intestinal-obstruction relief. There were multiple nodules on the mesentery. Each nodule had diverse morphology (Fig. 3B). The mucicarmine staining was positive for intraglandular content (Fig 3C). Immunohistochemical staining disclosed dot-like desmin positivity (Fig. 3D). Co-expression of panCK and vimentin was variable in each nodule. In the gland-forming portion, the tumor cells were strongly positive for panCK (Fig. 3E) and weakly positive for vimentin. Neuronal differentiation was also variable (Fig. 3F).

(A) The initial biopsy discloses typical findings of desmoplastic small round cell tumor; desmoplastic stroma, and variable sized nests of small round cells. (B) In the second biopsy specimen, there are multiple nodules, some of them (blue circle) show extensive glandular differentiation. (C) Mucicarmine staining is positive for intra-glandular content. (D-F) The immunohistochemical staining is also divergent for each nodule. The dot-like desmin reactivity is well demonstrated in a typical desmoplastic small round cell tumor appearing nodule (D), but pancytokeratin reactivity is strong in a glandular differentiated nodule (E), and the neuronal differentiation (CD56) is variable (F).

Follow-up

Despite the diagnosis of DSRCT, the patient refused chemotherapy and the disease rapidly progressed. The patient passed away a year after the first biopsy due to the increase in size and volume of the intra-abdominal masses and associated complications (intestinal and ureteral obstruction, hydronephrosis, and chronic renal failure).

DISCUSSION

DSRCT is a rare neoplasm, usually affecting adolescent male patients.1 It is difficult to distinguish from other small round cell tumors, because the cytological findings consistently include the following features: loosely clustered cellular population of round, oval, or spindled blue cells with scant cytoplasm, irregular nuclear membranes, finely granular chromatin, and inconspicuous nucleoli. Differential diagnoses are mainly Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumour, small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, malignant lymphoma, embryonal/alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, and neuroblastoma/Wilms tumor. Ultimately, cytologic differentiation is limited. To the diagnosis of DSRCT, however, can be established using the correlation of the clinical, cytological, and immunohistochemical features.2-4 Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is associated with a much older patient population and usually originates in the lung. Neuroblastoma and Wilms tumors, however, occur in very young children. High-grade lymphoma often demonstrates a diffuse growth pattern and does not exhibit the characteristic cohesion of DSRCT. The most distinct cytological feature of DSRCT compared to the other small round cell tumors, is its stromal fibrillary fragment, which is not a commonly found in body fluid, and can only be found using fine-needle aspiration cytology. In the case presented herein, there were occasional slender fragments of fibrillary tissue in the peritoneal-washing fluid, which were mixed with dis-cohesive single tumor cells but were not noted in the pleural fluid.

Immunohistochemically, DSRCT may show a various differentiation, which is a striking feature of the tumor. Typically, tumor cells are immunoreactive for epithelial (keratin and epithelial-membrane antigen), mesenchymal (vimentin), myogenic (desmin), and neural (neuron-specific enolase and CD56) markers. Immunostaining for desmin frequently shows a distinct staining pattern: namely, punctuate and perinuclear positivity. In this case, desmin immunostaining was diagnostic for DSRCT.

Attempts have been made to use immunocytochemical staining from small, round, blue cell tumor groups for the differential diagnosis of DSRCT.3 The results of the case presented herein are similar to those of the previous reported cases (vimentin [+], panCK [+], and desmin [weak+]). In this case, however, an additional interesting point is the divergent differentiation among different nodules. Each nodule showed that typical DSRCT had extended to extensive glandular differentiation, with mucicarmine-positive mucin content. The immunohistochemical profile is also quite for each nodule. The typical DSRCT nodule shows a weak epithelial marker and dot-like desmin positivity, but the extensive glandular-differentiated nodule is strongly positive for panCK and weakly positive/negative for vimentin and desmin. There is only one case report mentioning these various cytologic differentiations.5 In that paper, the same various cytologic differentiations are noted (inconspicuous to conspicuous nucleoli and with a different immunohistochemistry).

The most well known molecular event was a specific reciprocal translocation t(11; 22)(p13; 12). Shen et al.6 and Roberts et al.7 described a variant where other chromosomes were involved in addition to chromosomes 11 and 22. The translocation t(11; 22)(p13; 12) involves the EWS gene in 22q24 and the WT1 gene in 11p13. This translocation produces the chimeric transcript EWS/WT1 and the related WT1 protein, which can be detected immunohistochemically. The case presented herein, however, was negative for WT1. There have been some trials of the molecular diagnosis of small round cell tumors via fine-needle aspiration.8 In comparison, immunocytochemical analysis resolved 19/25 Ewing sarcomas (76%), nine (82%) of the 11 rhabdomyosarcomas, six (46%) of the 13 neuroblastomas, and one (50%) of the two DSRCTs. Overall, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction resolved 38 (86%) of 44 vs 35 (69%) of 51 cases through immunocytochemical analysis. There have been some reports of the molecular confirmation of DSRCT with a cytological sample.9

ThinPrep smear disclosed that the cytoplasm of tumor cells was well-preserved. The clusters, however, were more rounded with a three-dimensional structure than those of a conventional smear, and were thus very similar to adenocarcinoma. In some of the literatures, liquid-based cytomorphology in serous fluid could be used to make an accurate diagnosis, as it showed excellent morphology against a clear background, with preservation of the three-dimensional configuration and a sufficient amount of extracellular material.10 In our pleural fluid case, the liquid-based cytology smear showed more glandular differentiation than a conventional smear, including enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and an extracellular mucinous material. Therefore, we should carefully examine ThinPrep smear compared to the conventional smear for cytologic differential diagnosis of DSRCT from adenocarcinoma.

In conclusion, the cytological diagnosis of DSRCT via cytomorphology is very difficult. Clinicopathologic consideration and adjunctive immunocytochemistry and molecular study would be helpful for avoiding the misdiagnosis of "disseminated adenocarcinoma."

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Inje University Research Foundation (20110767).

Notes

This subject was presented at 2011 Korean-Japanese Cytopathology meeting (Poster#16).

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.