Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Pathol Transl Med > Forthcoming articles > Article

-

Original Article

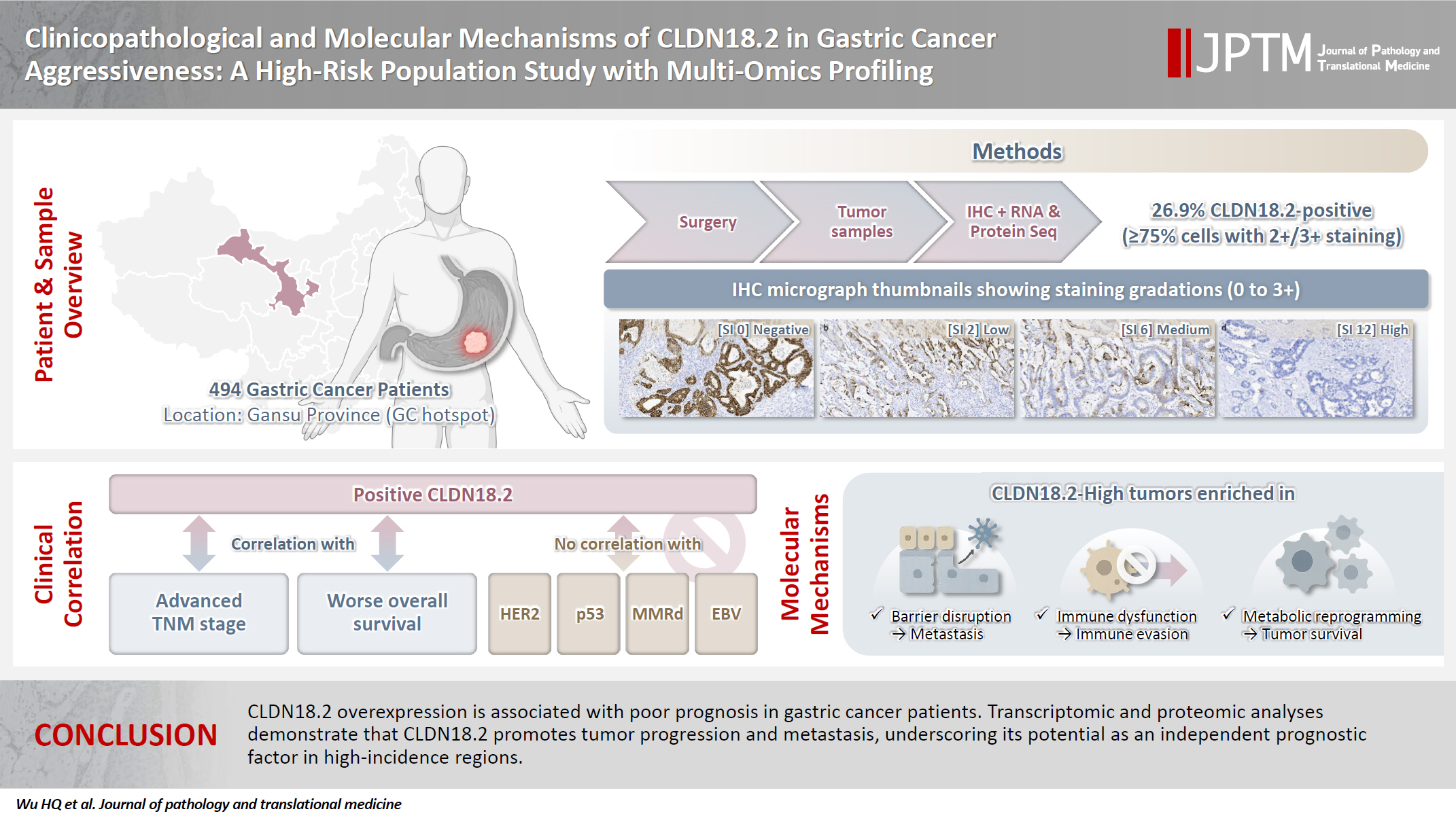

Clinicopathological and molecular mechanisms of CLDN18.2 in gastric cancer aggressiveness: a high-risk population study with multi-omics profiling -

Hengquan Wu1,2,3,4,*

, Mei Li1,3,4,*

, Mei Li1,3,4,* , Gang Wang2,3,4,5

, Gang Wang2,3,4,5 , Peiqing Liao1,2,3,4

, Peiqing Liao1,2,3,4 , Peng Zhang1,3,4

, Peng Zhang1,3,4 , Luxi Yang1,2,3,4

, Luxi Yang1,2,3,4 , Yumin Li1,2,3,4

, Yumin Li1,2,3,4 , Tao Liu1,2,3,4,5

, Tao Liu1,2,3,4,5 , Wenting He1,2,3,4,5

, Wenting He1,2,3,4,5

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2025.09.11

Published online: January 5, 2026

1The Second Hospital & Clinical Medical School, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China

2Gansu Provincial Key Laboratory of Environmental Oncology, Lanzhou, China

3Digestive System Tumor Prevention and Treatment and Translational Medicine Engineering Innovation Center of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China

4Digestive System Tumor Translational Medicine Engineering Research Center of Gansu Province, Lanzhou, China

5School of Basic Medical Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China

-

Corresponding Author Wenting He, PhD, The Second Hospital & Clinical Medical School, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730030, China Tel: +86-09315190901, E-mail: hewt@lzu.edu.cn

Tao Liu, PhD, The Second Hospital & Clinical Medical School, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730030, China Tel: +86-09318943240, Fax: +86-09318458109, E-mail: liut@lzu.edu.cn - *Hengquan Wu and Mei Li contributed equally to this work.

© The Korean Society of Pathologists/The Korean Society for Cytopathology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 123 Views

- 15 Download

Abstract

-

Background

- The tight junction protein claudin18.2 (CLDN18.2) has been implicated in poor prognosis and suboptimal immunotherapy response in gastric cancer (GC). This study investigates the clinicopathological relevance of CLDN18.2 expression and its association with molecular subtypes in GC patients from a high-incidence region, combining transcriptomic and proteomic approaches to explore how CLDN18.2 contributes to progression and metastasis.

-

Methods

- A retrospective cohort of 494 GC patients (2019–2024) underwent immunohistochemical analysis for CLDN18.2, Epstein-Barr virus (Epstein–Barr virus–encoded RNA), p53, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and mismatch repair proteins (MLH1, MSH2, PMS2, and MSH6). CLDN18.2 positivity was defined as moderate to strong (2+/3+) membranous staining in ≥75% of tumor cells. Clinicopathological correlations, biomarker associations, and survival outcomes were evaluated. Transcriptomic and proteomic sequencing was performed to explore molecular mechanisms.

-

Results

- CLDN18.2 positivity was observed in 26.9% (133/494) of gastric adenocarcinomas. CLDN18.2-positive tumors correlated with TNM stage (p = .003) and shorter overall survival (p = .018). No associations were identified with age, sex, HER2 status, microsatellite instability, or Epstein-Barr virus infection. Transcriptomic profiling revealed CLDN18.2-high tumors enriched in pathways involving cell junction disruption, signaling regulation, and immune modulation. Proteomic profiling showed that tumors with high CLDN18.2 were enriched in multiple mechanism-related pathways such as integrated metabolic reprogramming, cytoskeletal recombination, immune microenvironment dysregulation, and pro-survival signaling. These mechanisms may collectively contribute to tumor progression and metastasis.

-

Conclusions

- CLDN18.2 overexpression is associated with poor prognosis in GC patients. Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses demonstrate that CLDN18.2 promotes tumor progression and metastasis, underscoring its potential as an independent prognostic factor in regions with a high incidence of GC.

- Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common malignancy and cause of cancer mortality globally, with approximately one million new cases diagnosed annually [1]. Despite advances in diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, clinical outcomes for advanced GC remain dismal, with limited patient eligibility for targeted therapies and a 5-year survival rate less than 30% [2-4]. This underscores the urgent need to elucidate molecular drivers of tumor progression and identify biomarkers for precision medicine.

- Gastric adenocarcinoma is characterized by profound molecular heterogeneity, complicating efforts to standardize treatment paradigms [5]. While the Lauren classification has historically guided clinical management, its utility in predicting therapeutic responses remains constrained [6]. Landmark work by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) redefined GC into four molecular subtypes of chromosomally unstable, microsatellite unstable, genomically stable, and Epstein-Barr virus–positive (EBV+) tumors, providing a framework for molecularly stratified therapies [7]. However, the clinical translation of these subtypes remains uncertain, necessitating the discovery of actionable biomarkers to refine patient stratification.

- Claudin18.2 (CLDN18.2), a splice variant of the tight junction protein claudin18, has emerged as a promising therapeutic target [8]. It is confined to gastric mucosal tight junctions in normal tissues but is exposed on the surface upon malignant transformation [9,10]. In addition to GC, aberrant CLDN18.2 expression is observed in pancreatic, biliary, ovarian, and lung adenocarcinomas, positioning it as a selective biomarker [11].

- Preclinical and clinical studies, including trials of the monoclonal antibody zolbetuximab (formerly IMAB362) and antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) targeting CLDN18.2, have demonstrated significant antitumor efficacy in CLDN18.2-high GC subsets [12,13]. For instance, the phase III SPOTLIGHT and GLOW trials validated zolbetuximab combined with chemotherapy as a first-line regimen for CLDN18.2-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–negative advanced GC, achieving median overall survival (OS) of 18.23 months and 14.39 months, respectively [9,14]. Additionally, novel ADCs such as CMG901 (AZD0901) demonstrated an objective response rate of 28%–29% and median OS of 10.1 months in a phase I trial for refractory GC [15].

- Despite advances in CLDN18.2-targeted therapies, its expression exhibits heterogeneity across geographical regions and ethnic groups. In Gansu Province, a global GC hotspot with elevated incidence linked to the arid climate and high dietary nitrosamines, our prior analysis of 75,522 GC patients (2013–2021) identified climatic factors as key contributors to GC risk [16]. To address the research gap of CLDN18.2 in this region, we conducted a comprehensive multi-omics investigation encompassing immunohistochemistry (IHC), transcriptomic profiling, and proteomic analysis in 494 GC patients from this region. This study evaluated the relationships between CLDN18.2 expression and molecular subtype, clinicopathological features, and survival outcomes and further explored its potential mechanisms in GC progression and metastasis.

INTRODUCTION

- Case selection

- During the period 2019–2024, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of 510 patients with gastric adenocarcinoma who underwent radical surgical resection in the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University. All specimens were obtained surgically in patients who had not undergone neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

- Patient inclusion criteria were (1) preoperative endoscopic biopsy-confirmed GC; (2) indications for GC surgery; (3) eligible for curative resection; (4) adequate function of other organ systems to tolerate surgery, without comorbidities (such as severe cardiac, cerebral, pulmonary, or metabolic diseases) significantly impacting surgical risk; (5) informed consent by both the patient and their family for curative GC resection; and (6) availability of complete medical records. Patient exclusion criteria were (1) unsuitable for curative GC surgery (defined as R0 resection with D2 lymphadenectomy) due to invasion of adjacent organs or concurrent other tumors; (2) significant comorbidities potentially impacting the surgery; (3) presentation as a surgical emergency; (4) refusal of the surgical plan by either the patient or their family; and (5) incomplete medical records or patient withdrawal from the study.

- After excluding 16 ineligible samples, the final cohort comprised 494 patients. Clinicopathological data were systematically collected, including demographic variables (sex, age), diagnosis schedule (date of initial diagnosis), tumor characteristics (grade, location, histotype, Lauren classification), biomarker profiles (HER2, p53, Epstein–Barr virus–encoded RNA [EBER], MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PMS2), and OS outcomes. Tissue specimens were fixed in formalin within 48 hours post-resection and processed according to standardized histopathological protocols.

- Immunohistochemistry

- IHC analyses on fresh-frozen paraffin-embedded specimens were conducted using a fully automatic slide stainer, the Ventana Benchmark Ultra automated staining platform (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland), with the Ultra View DAB detection kit. HER2 (Kit-0043, MXB), p53 (MAB-0674, MXB), PMS2 (RMA-0775, MXB), MSH2 (MAB-0836, MXB), MSH6 (MAB-0831, MXB), MLH1 (MAB-0838, MXB), EBER, and all immunoreagents were obtained from Ventana Medical Systems (Roche Diagnostics).

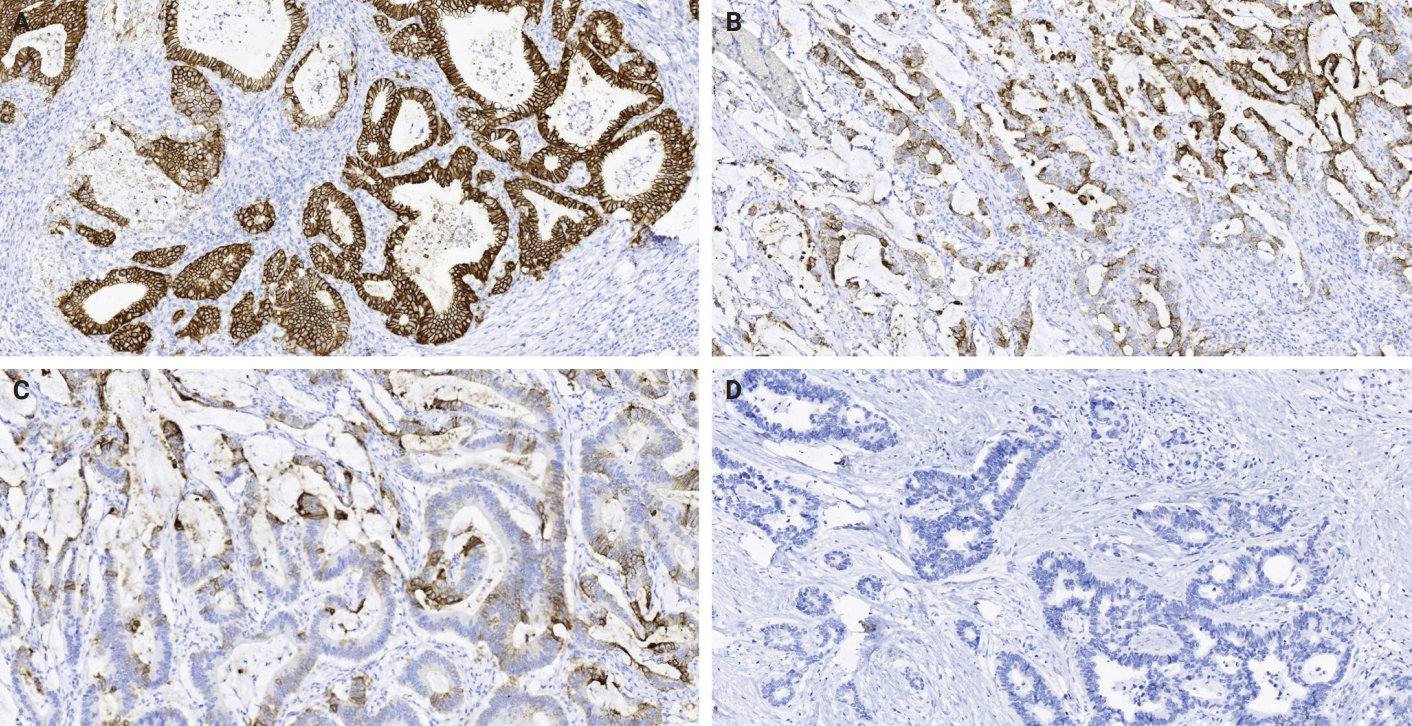

- CLDN18.2 expression was assessed using a polyclonal antibody (1:500 dilution, ab222513, Immunoway, San Jose, CA, USA) through immunohistochemical analysis. Two experienced pathologists independently evaluated the cytoplasmic staining patterns based on established criteria. Staining intensity was graded as strong (3+), moderate (2+), weak (1+), or absent (0), and the percentage of stained tumor cells was recorded. A staining index (SI) ranging from 0 to 12 was calculated by multiplying the intensity score by the percentage score. Based on predefined clinical thresholds, cases were categorized by expression intensity as absent (SI 0), weak (SI 1–2), moderate (SI 3–6), or strong (SI 8–12). Cases were classified according to a cut off of ≥75% tumor cell 2+ or 3+ intensity, which is the eligible IHC cut-off for an ongoing zolbetuximab study [17]. In samples undergoing RNA and protein sequencing, high CLDN18.2 expression is defined as immunohistochemical staining intensity ≥2+ in ≥75% of tumor cells, while low CLDN18.2 expression is defined as staining intensity <2+ in ≥40% of tumor cells.

- Mismatch repair deficiency (MMRd) was determined by loss of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2 on IHC [18]. p53 status was defined as wild-type (patchy nuclear staining) or aberrant (diffuse or complete loss) [19]. HER2 status assessment for gastric adenocarcinoma requires IHC testing, with specimens classified as negative (IHC 0/1+: no/faint reactivity), equivocal (IHC 2+: weak-moderate membranous reactivity in ≥10% tumor cells), or positive (IHC 3+: strong membranous reactivity in ≥10% tumor cells). Equivocal cases require confirmation via in situ hybridization (ISH), where positivity is defined as HER2:CEP17 ratio ≥2 or HER2 copy number ≥6.0 signals/cell; IHC 0/1+ or 3+ results preclude additional ISH testing [20].

- EBER in situ hybridization

- EBV infection was detected using the ISH EBER Probe (MC-3003, MXB) on the Ventana platform per manufacturer guidelines.

- RNA and protein sequencing

- Paired tumor and adjacent normal tissues from eight gastric adenocarcinoma patients were collected as fresh-frozen samples, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until processing. For RNA extraction, tissues were homogenized in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After chloroform phase separation, RNA was precipitated with isopropanol, washed with 75% ethanol, air-dried, and dissolved in RNase-free water. RNA integrity was verified via agarose gel electrophoresis (1% gel; 120 V, 20 minutes), confirming distinct 18S/28S ribosomal RNA bands without degradation. Only high-quality RNA (RNA integrity number > 7.0 implied by gel assessment) was used for cDNA synthesis.

- For protein extraction, tissues were mechanically disrupted in lysis buffer (8 M urea, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate) using a glass homogenizer, followed by centrifugation (14,000 ×g, 20 minutes, 4°C). The supernatant was collected, and total protein was quantified via BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Quality control was performed using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (12% gel; 80 V, 2 hours), ensuring intact protein bands without smearing.

- Subsequent RNA sequencing included reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction–based cDNA amplification, Illumina-compatible paired-end library preparation, and sequencing on the HiSeq platform. For proteomics, proteins were denatured, reduced (10 mM dithiothreitol), alkylated (50 mM iodoacetamide), and digested with trypsin (2 hours, 37°C). Peptides were desalted (C18 SPE), fractionated (high-pH reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography), lyophilized, reconstituted, separated via nano-LC (C18 column), and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry. A data-dependent acquisition spectral library was generated; differential proteins were identified using Spectronaut (v16.1), with functional enrichment (Gene Ontology [GO]/Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes [KEGG]) and subcellular localization analyses.

- Statistical analysis

- Associations between CLDN18.2 and clinicopathological variables were assessed using χ2 or Fisher’s exact test (significance threshold: p < .05). The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were used to calculate the survival curve. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software ver. 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The statistical results were plotted using GraphPad Prism 9.1.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

- Clinicopathological correlates and prognostic significance of CLDN18.2 expression in primarily resected gastric adenocarcinomas

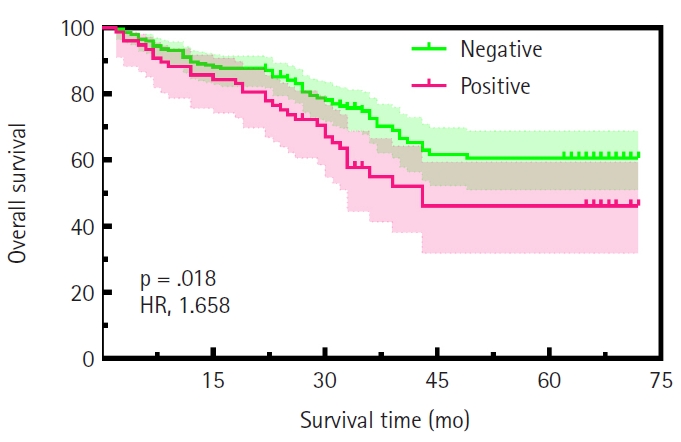

- The study cohort comprised 494 gastric adenocarcinoma patients, comprising 380 males (76.9%) and 114 females (23.1%), with a mean age of 58.54 ± 9.66 years (median, 59 years; range, 22 to 85 years) (Table 1). All patients underwent surgical resection of the primary tumor with an R0 margin. Tumor localization analysis revealed that nearly half of the cases originated in the gastric antrum, while 23.1% and 22.9% were located in the gastric fundus and body, respectively. Pathological staging demonstrated distinct distributions: pT4a and pT4b tumors predominated in pathological tumor (pT) staging (n = 276, 55.8%), whereas pathological nodal (pN) staging showed a higher frequency of pN0 (n = 171, 34.6%). TNM staging classified 22.3% (n = 110) as stage I, 20. 9% (n= 103) as stage II, and 56.8% (n = 281) as stage III–IV. Among them, 200 cases received postoperative chemotherapy, while 81 cases did not (Supplementary Fig. S1). Histologically, 8.5% (n = 42) of tumors were graded as G1, 55.3% (n = 273) as G2, and 36.2% (n = 179) as G3. Lauren classification categorized 31.8% (n = 157) as intestinal type, 40.9% (n=202) as diffuse type, and 27.3% (n = 135) as mixed type. The results demonstrated significant associations of CLDN18.2-positive status with pT category (p = .046), pN category (p = .013), and TNM stage (p = .003). No significant correlations were observed with age, sex, tumor location, histological grade, or Lauren subtype (Table 1). Representative immunohistochemical staining patterns of CLDN18.2 expression are presented in Fig. 1. Our survival analysis revealed that CLDN18.2-positive expression was associated with significantly shorter OS (p = .018) (Fig. 2).

- Characteristics of molecular biomarkers

- MMRd was identified in 6.3% (n = 31) of cases, with 93.7% (n = 463) demonstrating mismatch repair proficiency. EBV infection was detected in 2.0% (n=10) of tumors, while 98.0% (n = 484) tested negative. HER2 overexpression or amplification was observed in 16.2% (n = 80) of cases, while 83.8% (n = 414) lacked HER2 alterations. TP53 abnormalities were present in 46.8% (n=231) of cases, accounting for approximately half of the total cohort (Table 2). No correlation between the expression of CLDN18.2 and MMRd, HER2, TP53, or EBER-ISH was found.

- Analysis of the biological function of genes significantly related to CLDN18.2 by RNA sequencing

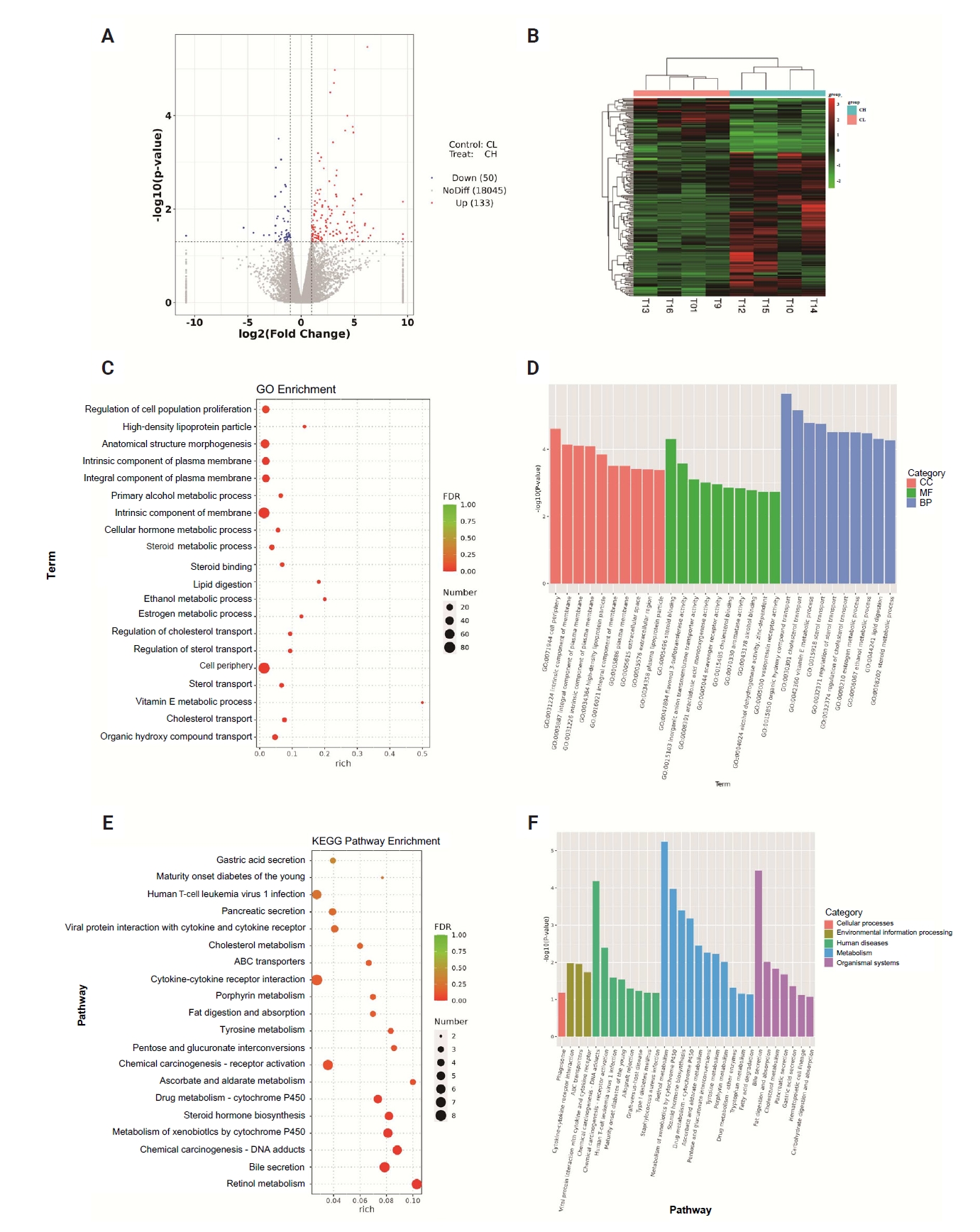

- We divided the eight pairs of tissue samples after sequencing into high CLDN18.2 expression (n = 4) and low expression (n = 4) groups. Compared with the low-expression group, the high-expression group showed 183 genes that were significantly differentially expressed and strongly correlated with CLDN18.2, including 133 upregulated and 50 downregulated genes (Fig. 3A, B). This indicates that broad transcriptional reprogramming is associated with CLDN18.2 overexpression. GO enrichment analysis across cellular components, molecular function, and biological processes identified functional clusters in CLDN18.2-high tumors (Fig. 3C, D). Cellular component enrichment predominantly comprised terms related to membrane integrity, including cell periphery, intrinsic membrane component, and integral plasma membrane component. Molecular function analysis highlighted steroid binding, flavonol 3-sulfotransferase activity, and inorganic anion transmembrane transporter activity. Biological process terms were enriched in pathways governing organic hydroxy compound transport, cholesterol transport, and vitamin E metabolism. KEGG pathway analysis further identified significant enrichment in phagosomes, cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, and chemical carcinogenesis (Fig. 3E, F). These results suggest that CLDN18.2 may influence tumor progression and metastasis via mechanisms involving cell junction disruption, signaling pathway regulation, and immune regulation.

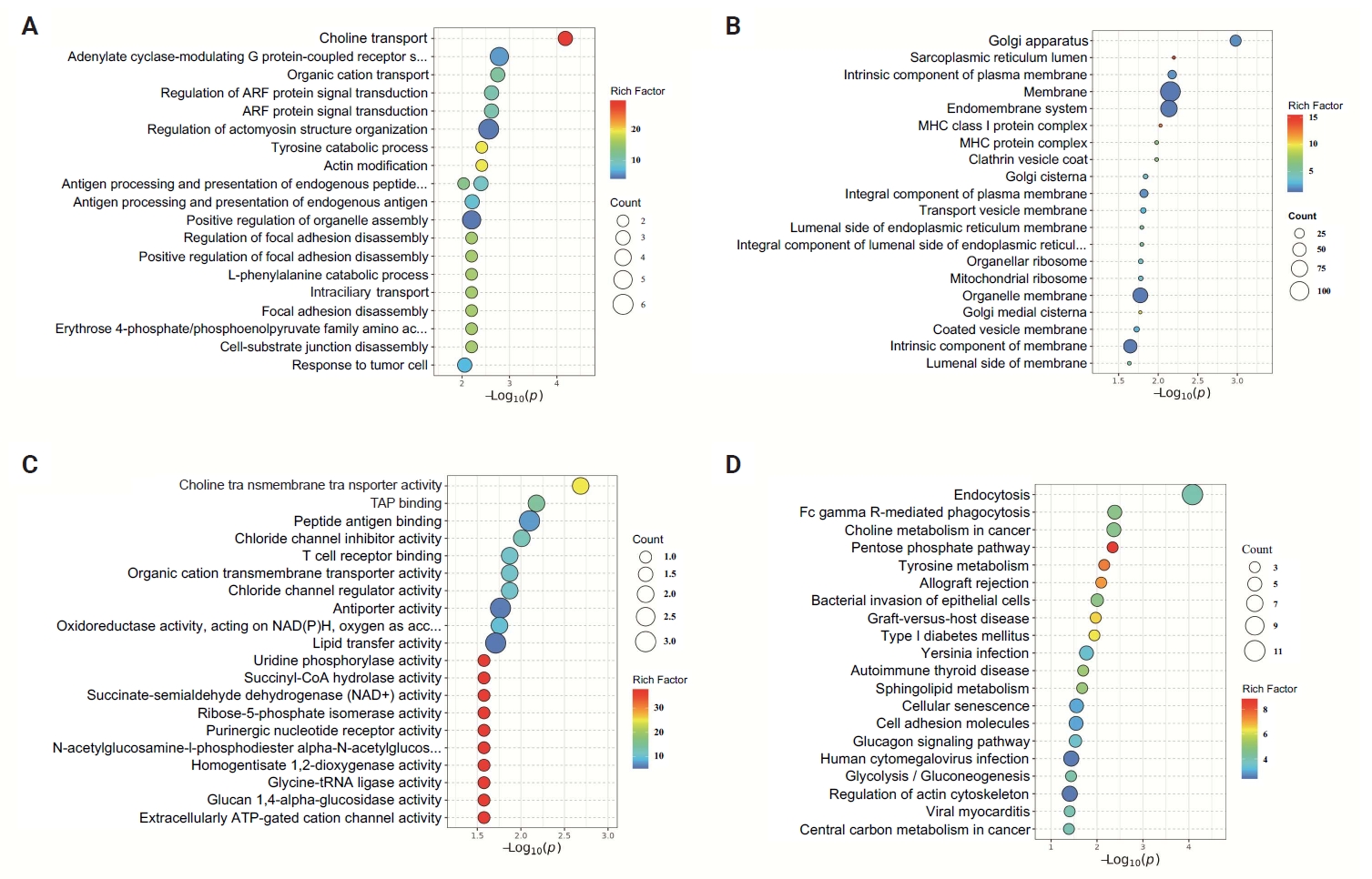

- Analysis of the biological functions of genes significantly associated with CLDN18.2 on proteome sequencing

- Based on proteome sequencing analysis, the CLDN18.2 high-expression group was mainly enriched in choline transport, adenylyl cyclase-G-protein-coupled receptor signal regulation, and regulation of actomyosin structure organization in biological processes (Fig. 4A). Cellular component analysis highlighted dysregulation of the Golgi apparatus, membrane, and endomembrane system, suggesting roles in secretory pathway activation and cell polarity disruption (Fig. 4B). In terms of molecular function, choline transmembrane transporter activity, TAP binding, peptide antigen binding, T-cell receptor binding, and chloride channel inhibitor activity were abnormal (Fig. 4C). KEGG pathway analysis showed that endocytosis, FcγR-mediated phagocytosis, choline metabolism in tumors, and the pentose phosphate pathway jointly regulated metabolic reprogramming, immune microenvironment dysregulation, and pro-survival signaling, promoting the progression and metastasis of GC (Fig. 4D).

RESULTS

- CLDN18.2, a gastric system–specific tight junction protein, is normally localized to differentiated epithelial cells, maintaining mucosal barrier integrity via cell-cell adhesion. However, malignant transformation disrupts cell adhesion and polarity, leading to aberrant CLDN18.2 surface exposure, which may promote metastatic dissemination by compromising epithelial cohesion [9]. In this study, we analyzed CLDN18.2 expression in a high-incidence GC cohort, combining clinicopathological correlations, survival data, and multi-omics profiling to explore its role in tumor progression.

- While our findings demonstrate that CLDN18.2 positivity (26.9%, 133/494) was significantly associated with advanced TNM stage (p = .003) and shorter survival time (p = .018), underscoring its role in aggressive disease biology in our cohort, it is important to acknowledge conflicting evidence in the literature regarding its prognostic value. Recent meta-analyses, including studies by Park et al. [21] and Ungureanu et al. [22], as well as individual studies of comparable scale and population focus [23], have reported no significant association between CLDN18.2 expression and survival outcomes in GC [21-23]. Notably, we found no association between CLDN18.2 and molecular subtypes defined by EBER, HER2, MMRd, p53, or TCGA classification, suggesting that its prognostic value may transcend conventional molecular stratification in our dataset. These findings align with prior studies reporting CLDN18.2 as a stage-dependent biomarker [24]. While our cohort showed no association between CLDN18.2 and age, gender, Lauren classification, tumor grade, or tumor location, Kwak et al. [25] observed a significant correlation between CLDN18.2-positive GC and tumor location in the upper third of the stomach. This difference, along with the prognostic discrepancies highlighted above, may stem from variations in immunohistochemical scoring protocols or regional epidemiological factors, emphasizing the need for standardized CLDN18.2 assessment criteria.

- RNA sequencing revealed enriched genes regulating membrane integrity (e.g., cell periphery and plasma membrane components) in CLDN18.2-high tumors. This molecular signature suggests compromised tight junction function, likely resulting from malignant transformation that disrupts cellular polarity and exposes CLDN18.2 on the cell surface. Preclinical data indicate that aberrant CLDN18.2 expression may contribute to cancer progression, but its direct role in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition remains unconfirmed in clinical studies [26]. Molecular function indicated that CLDN18.2 is linked to steroid binding and inorganic anion transport, implicating roles in lipid metabolism and ion homeostasis. Studies show that CLDN18 loss disrupts transcellular chloride flux and activates YAP/TEAD signaling, which can drive lipid and sterol biosynthesis. The steroid-binding signal likely reflects indirect effects via lipid-handling or steroid-responsive pathways rather than direct ligand binding, suggesting that altered ion transport and lipid metabolism are mechanistically coupled in the CLDN18.2-deficient gastric epithelium [27-29]. Biological processes such as organic hydroxy compound transport and vitamin E metabolism further highlighted metabolic reprogramming toward redox balance and biosynthetic support [30]. KEGG pathway analysis revealed enrichment in phagosomes, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, and chemical carcinogenesis, suggesting that CLDN18.2 synergizes with immune dysregulation and pro-carcinogenic signaling to drive cancer progression [24,31].

- Proteomic profiling corroborated the role of CLDN18.2 in cytoskeletal remodeling and metabolic adaptation. Notably, KEGG analysis identified aberrant endocytosis as a central mechanism, wherein CLDN18.2 may enhance nutrient internalization to sustain proliferation in nutrient-scarce microenvironments [23,32,33]. Concurrent dysregulation of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis and T-cell receptor binding implies that CLDN18.2 fosters immune evasion by perturbing antigen presentation or sequestering immunostimulatory molecules [34]. These perturbations collectively establish an immunosuppressive niche conducive to metastatic outgrowth.

- The relationship between CLDN18.2 and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in GC remains uncertain, with studies reporting conflicting findings. Several groups have found no significant correlation between these biomarkers, suggesting they may independently inform treatment strategies; for example, Ogawa et al. [35] reported that CLDN18.2 expression did not correlate with PD-L1, indicating that anti–programmed death-1 (PD-1)/PD-L1 therapy might not benefit CLDN18.2-positive patients. However, other studies suggest a potential interaction, such as Wang et al. [36], who observed a positive correlation between CLDN18.2 and PD-L1 expression, and Tao et al. [23], whose GSEA revealed significant enrichment of PD-1 signaling in CLDN18.2-high tumors. Clinically, the presence or absence of this overlap is highly relevant, particularly with the recent approval of the anti-CLDN18.2 agent zolbetuximab. Divergent reports regarding co-expression rates underscore the necessity for further research to correlate expression patterns with therapeutic outcomes [37].

- A limitation of this study is that the patients included in the analysis are from a single institution and underwent a relatively short follow-up period, which may introduce selection bias. The small proteomic subset limits mechanistic generalizability, warranting validation in larger cohorts.

- In this study, we demonstrate that elevated CLDN18.2 expression is significantly associated with TNM stage and OS in GC patients from high-incidence regions. Integrated transcriptomic and proteomic analyses revealed that CLDN18.2 drives progression via metabolic reprogramming, cytoskeletal remodeling, and immune dysregulation, establishing it as a key metastasis regulator and potential target for high-risk GC. The prognostic value of CLDN18.2 is pronounced in environmentally high-risk populations, with identified pathways (e.g., endocytosis, FcγR-mediated immune suppression) informing the suitability of combination therapies targeting CLDN18.2 and downstream effectors.

DISCUSSION

Supplementary Information

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval for the use of tissue samples in this research was granted by the Ethical Review Committee of Lanzhou University Second Hospital (IRB No. 2021A-153), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Availability of Data and Material

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: WH, TL. Data curation: WH, ML, HW, PZ, GW, LY, YL. Formal analysis: HW. Funding acquisition: WH, TL. Investigation: WH, ML, HW, GW, PL. Methodology: WH, TL. Project administration: WH, TL. Resources: WH, TL, ML. Supervision: WH, TL. Validation: WH, ML, HW. Visualization: HW. Writing—original draft: HW. Writing—review & editing: TL, WH. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by The Fundamental Research Funds for The Science and Technology Program of Gansu Province (No. 23JRRA1015); International science and technology cooperation project of Gansu Provincial Science and Technology Department (No. 2023YFWA0009).

- 1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024; 74: 229-63. ArticlePubMed

- 2. Shi D, Yang Z, Cai Y, et al. Research advances in the molecular classification of gastric cancer. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2024; 47: 1523-36. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 3. Matsuoka T, Yashiro M. Molecular insight into gastric cancer invasion: current status and future directions. Cancers (Basel) 2023; 16: 54.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 4. Kahraman S, Yalcin S. Recent advances in systemic treatments for HER-2 positive advanced gastric cancer. Onco Targets Ther 2021; 14: 4149-62. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 5. Zhang M, Hu S, Min M, et al. Dissecting transcriptional heterogeneity in primary gastric adenocarcinoma by single cell RNA sequencing. Gut 2021; 70: 464-75. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Ye Y, Yang W, Ruan X, et al. Metabolism-associated molecular classification of gastric adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol 2022; 12: 1024985.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014; 513: 202-9. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 8. Sahin U, Koslowski M, Dhaene K, et al. Claudin-18 splice variant 2 is a pan-cancer target suitable for therapeutic antibody development. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 7624-34. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 9. Shitara K, Lordick F, Bang YJ, et al. Zolbetuximab plus mFOLFOX6 in patients with CLDN18.2-positive, HER2-negative, untreated, locally advanced unresectable or metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (SPOTLIGHT): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023; 401: 1655-68. ArticlePubMed

- 10. Sahin U, Schuler M, Richly H, et al. A phase I dose-escalation study of IMAB362 (Zolbetuximab) in patients with advanced gastric and gastro-oesophageal junction cancer. Eur J Cancer 2018; 100: 17-26. ArticlePubMed

- 11. Zhou KI, Strickler JH, Chen H. Targeting claudin-18.2 for cancer therapy: updates from 2024 ASCO annual meeting. J Hematol Oncol 2024; 17: 73.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 12. Qi C, Gong J, Li J, et al. Claudin18.2-specific CAR T cells in gastrointestinal cancers: phase 1 trial interim results. Nat Med 2022; 28: 1189-98. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 13. Qi C, Liu C, Gong J, et al. Claudin18.2-specific CAR T cells in gastrointestinal cancers: phase 1 trial final results. Nat Med 2024; 30: 2224-34. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 14. Shah MA, Shitara K, Ajani JA, et al. Zolbetuximab plus CAPOX in CLDN18.2-positive gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: the randomized, phase 3 GLOW trial. Nat Med 2023; 29: 2133-41. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 15. Ruan DY, Liu FR, Wei XL, et al. Claudin 18.2-targeting antibody-drug conjugate CMG901 in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (KYM901): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol 2025; 26: 227-38. ArticlePubMed

- 16. Huang B, Liu J, Ding F, Li Y. Epidemiology, risk areas and macro determinants of gastric cancer: a study based on geospatial analysis. Int J Health Geogr 2023; 22: 32.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 17. Klempner SJ, Lee KW, Shitara K, et al. ILUSTRO: Phase II multicohort trial of zolbetuximab in patients with advanced or metastatic Claudin 18.2-positive gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2023; 29: 3882-91. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 18. de la Fouchardiere C, Cammarota A, Svrcek M, et al. How do I treat dMMR/MSI gastro-oesophageal adenocarcinoma in 2025? A position paper from the EORTC-GITCG gastro-esophageal task force. Cancer Treat Rev 2025; 134: 102890.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Coati I, Lotz G, Fanelli GN, et al. Claudin-18 expression in oesophagogastric adenocarcinomas: a tissue microarray study of 523 molecularly profiled cases. Br J Cancer 2019; 121: 257-63. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 20. Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, et al. Gastric cancer, version 2.2025, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2025; 23: 169-91. ArticlePubMed

- 21. Park G, Park SJ, Kim Y. Clinicopathological significance and prognostic values of claudin18.2 expression in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2024; 14: 1453906.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 22. Ungureanu BS, Lungulescu CV, Pirici D, et al. Clinicopathologic relevance of Claudin 18.2 expression in gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2021; 11: 643872.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 23. Tao D, Guan B, Li Z, Jiao M, Zhou C, Li H. Correlation of Claudin18.2 expression with clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis in gastric cancer. Pathol Res Pract 2023; 248: 154699.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Liu S, Zhang Z, Jiang L, Zhang M, Zhang C, Shen L. Claudin-18.2 mediated interaction of gastric cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts drives tumor progression. Cell Commun Signal 2024; 22: 27.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 25. Kwak Y, Kim TY, Nam SK, et al. Clinicopathologic and molecular characterization of stages II-IV gastric cancer with Claudin 18.2 expression. Oncologist 2025; 30: oyae238.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 26. Kubota Y, Shitara K. Zolbetuximab for claudin18.2-positive gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2024; 16: 17588359231217967.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 27. Gaitan-Penas H, Apaja PM, Arnedo T, et al. Leukoencephalopathy-causing CLCN2 mutations are associated with impaired Cl(-) channel function and trafficking. J Physiol 2017; 595: 6993-7008. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 28. Caron TJ, Scott KE, Sinha N, et al. Claudin-18 loss alters transcellular chloride flux but not tight junction ion selectivity in gastric epithelial cells. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 11: 783-801. Article

- 29. Hagen SJ, Ang LH, Zheng Y, et al. Loss of tight junction protein Claudin 18 promotes progressive neoplasia development in mouse stomach. Gastroenterology 2018; 155: 1852-67. ArticlePubMed

- 30. Chiaramonte R, Sauro G, Giannandrea D, Limonta P, Casati L. Molecular insights in the anticancer activity of natural tocotrienols: targeting mitochondrial metabolism and cellular redox homeostasis. Antioxidants (Basel) 2025; 14: 115.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 31. Wu J, Lu J, Chen Q, Chen H, Zheng Y, Cheng M. Pan-cancer analysis of CLDN18.2 shed new insights on the targeted therapy of upper gastrointestinal tract cancers. Front Pharmacol 2024; 15: 1494131.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 32. Banushi B, Joseph SR, Lum B, Lee JJ, Simpson F. Endocytosis in cancer and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2023; 23: 450-73. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 33. Basagiannis D, Zografou S, Murphy C, et al. VEGF induces signalling and angiogenesis by directing VEGFR2 internalisation through macropinocytosis. J Cell Sci 2016; 129: 4091-104. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 34. Wu B, Wang Q, Li B, Jiang M. LAMTOR1 degrades MHC-II via the endocytic in hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 2022; 43: 1059-70. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 35. Ogawa H, Abe H, Yagi K, Seto Y, Ushiku T. Claudin-18 status and its correlation with HER2 and PD-L1 expression in gastric cancer with peritoneal dissemination. Gastric Cancer 2024; 27: 802-10. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 36. Wang C, Wang Y, Chen J, et al. CLDN18.2 expression and its impact on prognosis and the immune microenvironment in gastric cancer. BMC Gastroenterol 2023; 23: 283.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 37. Cho Y, Ahn S, Kim KM. PD-L1 as a biomarker in gastric cancer immunotherapy. J Gastric Cancer 2025; 25: 177-91. ArticlePubMedPDF

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link-

Cite this Article

Cite this Article

- Cite this Article

-

- Close

- Download Citation

- Close

- Figure

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Graphical abstract

| Characteristic | Total (n = 494) | CLDN18-negative | CLDN18-positive | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) (median, 59 yr) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 58.54 ± 9.66 | |||

| <59 | 246 (49.8) | 175 (71.1) | 71 (28.9) | .333 |

| ≥ 59 | 248 (50.2) | 186 (75.0) | 62 (25.0) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 380 (76.9) | 272 (71.6) | 108 (28.4) | .171 |

| Female | 114 (23.1) | 89 (78.1) | 25 (21.9) | |

| Gastric localization | ||||

| Fundus | 114 (23.1) | 85 (74.6) | 29 (25.4) | .802 |

| Body | 113 (22.9) | 80 (70.8) | 33 (29.2) | |

| Antrum | 267 (54.0) | 196 (73.4) | 71 (26.6) | |

| pT | ||||

| 1a–1b | 79 (16.0) | 67 (84.8) | 12 (15.2) | .046 |

| 2 | 64 (13.0) | 49 (76.6) | 15 (23.4) | |

| 3 | 75 (15.2) | 51 (68.0) | 24 (32.0) | |

| 4a–4b | 276 (55.8) | 194 (70.3) | 82 (29.7) | |

| pN | ||||

| 0 | 171 (34.6) | 137 (80.1) | 34 (19.9) | .013 |

| 1 | 63 (12.8) | 50 (79.4) | 13 (20.6) | |

| 2 | 120 (24.3) | 79 (65.8) | 41 (34.2) | |

| 3a-3b | 140 (28.3) | 95 (67.9) | 45 (32.1) | |

| TNM staging | ||||

| I | 110 (22.3) | 90 (81.9) | 20 (18.1) | .003 |

| II | 103 (20.9) | 82 (79.6) | 21 (20.4) | |

| III–IV | 281 (56.8) | 189 (67.3) | 92 (32.7) | |

| Tumor grading | ||||

| G1 | 42 (8.5) | 33 (78.6) | 9 (21.4) | .638 |

| G2 | 273 (55.3) | 196 (71.8) | 77 (28.2) | |

| G3 | 179 (36.2) | 132 (73.7) | 47 (26.3) | |

| Lauren | ||||

| Intestinal | 157 (31.8) | 125 (79.6) | 32 (20.4) | .077 |

| Diffuse | 202 (40.9) | 140 (69.3) | 62 (30.7) | |

| Mixed | 135 (27.3) | 96 (71.1) | 39 (28.9) |

| Characteristic | Total (n = 494) | CLDN18-negative | CLDN18-positive | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMRd | ||||

| Yes | 31 (6.3) | 23 (74.2) | 8 (25.8) | .885 |

| No | 463 (93.7) | 338 (73.0) | 125 (27.0) | |

| HER2 | ||||

| Positive | 80 (16.2) | 53 (66.3) | 27 (33.8) | .133 |

| Negative | 414 (83.8) | 308 (74.4) | 106 (25.6) | |

| p53 | ||||

| Altered | 231 (46.8) | 168 (72.8) | 63 (27.2) | .870 |

| Wild type | 263 (53.2) | 193 (73.4) | 70 (26.6) | |

| EBER | ||||

| Positive | 10 (2.0) | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | .193 |

| Negative | 484 (98.0) | 356 (73.6) | 128 (26.4) |

Values are presented as number (%). GC, gastric cancer; CLDN18.2, claudin18.2; SD, standard deviation.

Values are presented as number (%). CLDN18.2, claudin18.2; MMRd, mismatch repair deficiency; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; EBER, Epstein–Barr virus–encoded RNA.

E-submission

E-submission