Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Pathol Transl Med > Forthcoming articles > Article

-

Review Article

Solitary fibrous tumor: an updated review -

Joon Hyuk Choi

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2025.10.08

Published online: December 29, 2025

Department of Pathology, Yeungnam University College of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

- Corresponding author: Joon Hyuk Choi, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology, Yeungnam University College of Medicine, 170 Hyeonchung-ro, Nam-gu, Daegu 42415, Korea Tel: +82-53-640-6754, Fax: +82-53-640-6769, E-mail: joonhyukchoi@ynu.ac.kr

© The Korean Society of Pathologists/The Korean Society for Cytopathology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 166 Views

- 16 Download

Abstract

- Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is a fibroblastic neoplasm characterized by a branching, thin-walled dilated staghorn-shaped (hemangiopericytoma-like) vasculature and a NAB2::STAT6 gene fusion. SFTs can occur in almost any anatomical location, including superficial and deep soft tissues, visceral organs, and bone. They most commonly occur in extrapleural locations, equally affect both sexes, and are typically present in adults. Although metastasis is rare, SFTs frequently show local recurrence. The diagnosis of SFTs is difficult because of their broad histological and morphological overlap with other neoplasms. An accurate diagnosis is important for guiding disease management and prognosis. Despite advances in molecular diagnostics and therapeutic strategies, the biological complexity and unpredictable clinical behavior of SFTs present significant challenges. This review provides an updated overview of SFT, with a focus on its molecular genetics, histopathological features, and diagnostic considerations.

- Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is a rare fibroblastic neoplasm defined by a distinctive network of thin-walled, branching staghorn-shaped (hemangiopericytoma-like) vessels [1]. It may occur in almost any anatomical location, such as superficial and deep soft tissue, visceral organs, and bone, although it most often arises in extrapleural sites. SFT affects both sexes equally and is typically diagnosed in adults.

- Many tumors previously classified as hemangiopericytomas are now recognized as SFTs and reflect fibroblastic rather than true pericytic differentiation [2]. Histologically, SFTs exhibit a wide morphological spectrum, usually consisting of spindle to ovoid cells arranged haphazardly within a collagen-rich stroma and associated with prominent staghorn-shaped vasculature [3]. However, its biological behavior is often unpredictable and cannot be reliably inferred from morphology alone [4].

- Recent advances in molecular pathology, particularly the discovery of the NAB2::STAT6 gene fusion and its downstream effects, have provided considerable insight into the biology, classification, and potential therapeutic targets of SFT [5-7]. Nonetheless, diagnosis remains difficult because of marked histological heterogeneity and overlap with other spindle cell neoplasms.

- Most SFTs pursue an indolent course; however, a clinically important subset shows aggressive behavior, including local recurrence or distant metastasis. Therefore, accurate pathological classification, integrated with molecular findings, is essential for guiding management and prognostication.

- In this review, the clinicopathological and molecular features of SFT are summarized, including the histological subtypes, diagnostic approaches, and key differential diagnoses.

INTRODUCTION

- The term hemangiopericytoma was first introduced in the 1940s by Stout and Murray [8] and Stout [9,10] to describe tumors thought to originate from pericytes, which are specialized contractile cells surrounding capillaries and venules; however, their original definition lacked specificity and encompassed a heterogeneous group of neoplasms, including entities now classified as myofibromas. In 1976, Enzinger and Smith [11] refined the concept, characterizing these tumors by their undifferentiated small round-to-spindle cells and the presence of prominent, branching staghorn-shaped vessels. Despite this refinement, its classification remains problematic because of inconsistent ultrastructural evidence of pericytic differentiation [12-15], infrequent actin expression [16-19], and poor diagnostic reproducibility [20], which has resulted in a gradual decline in the use of the term.

- The entity known as SFT subsequently emerged. First described by Klemperer and Rabin [21] as a pleural-based lesion designated “fibrous mesothelioma” or “benign fibrous tumor of the pleura,” it was more clearly defined by England in 1989 [22], who proposed the term “localized fibrous tumor of the pleura.” By the late 1980s and early 1990s, histologically indistinguishable tumors were increasingly recognized at extrapleural sites, which supported the concept of a broader, site-independent lesion.

- Extrapleural tumors with a hemangiopericytoma-like morphology frequently express CD34, similar to SFTs, which suggests a shared lineage. This was confirmed by the discovery of the recurrent NAB2::STAT6 gene fusion and its corresponding nuclear signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) expression in SFTs and tumors, which were previously diagnosed as hemangiopericytomas, regardless of anatomical site [23-26].

- Based on this evidence, the 2002 WHO classification of tumors of soft tissue and bone (3rd edition) [27] revised the definition of hemangiopericytoma. It was recognized that most remaining cases closely resemble the cell variant of SFT morphologically and clinically. In 2013, the 4th edition of the WHO classification [28] eliminated the term hemangiopericytoma, reclassifying nearly all such tumors under the unified diagnosis of SFT. Table 1 lists the conceptual changes in hemangiopericytoma classification.

HISTORICAL ASPECTS

- SFTs affect both sexes equally and predominantly occur in adults, with a peak incidence between 40 and 70 years of age [29-31]. Although SFTs may arise anywhere in the body, extrapleural locations are more common. Approximately 30%–40% occur in the extremities, 30%–40% in the deep soft tissues of the abdomen, pelvis, or retroperitoneum, 10%–15% in the head and neck, and 10%–15% in the trunk [30,32].

- In the gastrointestinal system, SFTs typically develop in adults aged 20–70 years, but are rare in children and adolescents. The liver, pancreas, mesentery, or serosal surfaces of the gastrointestinal tract are considered common sites. A slight male predominance was reported in the lipomatous (fat-forming) subtype [33-35]. In the female genital tract, SFTs primarily affect women aged 22–75 years, with a peak incidence during the fifth decade. Common sites include the vulva, vagina, and cervix [36].

- In the thorax, SFTs primarily occur from the visceral pleura and typically present in the sixth decade. They may also arise in the lung or pericardium, whereas mediastinal involvement is rare. No sex predilection is evident [22,37]. In the central nervous system (CNS), SFTs are extremely rare and account for less than 1% of all CNS tumors. They often present in middle-aged to older adults. Most are dural-based and are often located in the supratentorial region, with occasional cases reported in the skull base, spinal cord, or pineal region [38-40].

- In the urinary and male genital tracts, SFTs generally occur in adults between 20 and 70 years of age, with no clear sex predilection. Reported locations include the kidney, bladder, prostate, seminal vesicles, and penis [41,42]. In the endocrine system, SFTs most commonly involve the thyroid gland or pituitary fossa, whereas other endocrine organs are rare. These tumors typically occur between ages of 50 and 60, with no sex predilection [43,44].

- In the head and neck, a marked male predominance is observed in the larynx (male-to-female ratio ~6:1), whereas tumors arising in the orbit, nasal cavity, or paranasal sinuses occur across a broad age range in both sexes [45,46]. Orbital SFTs are most common in individuals in their mid-40s and are rare in children. These tumors may occur in the intraconal and extraconal compartments, with occasional involvement of the lacrimal gland, conjunctiva, or eyelid [47-49].

EPIDEMIOLOGY

- The clinical presentation of SFTs varies by anatomical site, but they most commonly manifest as a slow-growing, painless mass. Abdominopelvic SFTs may cause symptoms, such as abdominal distention, constipation, urinary retention, or early satiety [50,51], whereas head and neck lesions result in nasal obstruction, hoarseness, or epistaxis [52,53]. Orbital SFTs typically present with periorbital fullness, proptosis, globe displacement, and diplopia, whereas deeper lesions may compromise the optic nerve [47,49,54].

- Thoracic SFTs are often asymptomatic and incidentally detected; however, larger tumors can result in cough, dyspnea, or chest pain [55]. CNS SFTs generally present with mass effect symptoms or increased intracranial pressure [56]. In the digestive, urinary, and endocrine systems, tumors are usually painless but may produce compressive symptoms depending on their size and anatomical relationships [41,43,57].

- A subset of large or aggressive SFTs secretes insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2), which results in paraneoplastic hypoglycemia (Doege-Potter syndrome) and, rarely, acromegaloid features [58,59].

CLINICAL FEATURES

- Upon imaging, SFTs typically show nonspecific radiographic features [60,61], whereas computed tomography (CT) usually yields a well-defined, occasionally lobulated, isodense mass relative to the skeletal muscle (Fig. 1). They exhibit heterogeneous contrast enhancement because of their rich vascularity [62,63]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically shows intermediate T1 signal intensity and variable T2 signals, which correspond to fibrous (low T2) and cellular or myxoid (high T2) components [63-65]. Larger or more aggressive tumors may display heterogeneity because of fibrosis, necrosis, hemorrhage, or cystic changes [63].

- In the thorax, SFTs are usually present as sharply marginated, pleural-based masses without chest wall invasion. Malignant lesions may exhibit increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on positron emission tomography; however, overlap with benign tumors may occur [66,67]. In the CNS, SFTs often mimic meningiomas on imaging. The lesions exhibit isointensity on T1-weighted MRI, variable T2 signals, and peripheral dural enhancement (dural tail); however, no specific CT or MRI features reliably distinguish them from other dural-based tumors [68,69].

- In the head and neck region, SFTs typically appear as well-circumscribed, contrast-enhanced masses by CT and MRI [70,71]. In the orbit, MRI typically exhibits iso-intense signals on T1-weighted images, whereas CT demonstrates contrast enhancement and is valuable for assessing bone involvement [47,72].

RADIOLOGICAL FEATURES

- Most SFTs harbor a recurrent paracentric inversion on chromosome 12q13. This inversion results in the fusion of the NAB2 and STAT6 genes [26,73,74]. This fusion replaces the C-terminal repression domain of NAB2 with the transcriptional activation domain of STAT6, thereby converting NAB2 from a transcriptional repressor into a constitutive activator of EGR1. Consequently, EGR1 drives the expression of downstream targets, such as IGF2 and FGFR1, as well as other genes that promote growth and survival [73].

- Multiple NAB2::STAT6 gene fusion variants have been discovered, with the length of the retained STAT6 portion correlating with tumor morphology and clinical behavior. For example, fusions involving NAB2 exon 4 and STAT6 exon 2 or 3 are associated with a reduced cellular and more indolent course. In contrast, fusions involving NAB2 exons 6–7 and STAT6 exons 16–17 more commonly occur in cellular or clinically aggressive variants [75,76].

- No distinct molecular features have been identified that can reliably distinguish benign from malignant SFTs; however, other genetic alterations linked to high-grade transformation or aggressive behavior have been identified, including TERT promoter mutations [55,77], TP53 mutations, and p16 overexpression [78-81]. Moreover, IGF2, a key mediator of Doege-Potter syndrome in SFTs, is a target gene of EGR1 and may be dysregulated by the NAB2::STAT6 fusion, which may account for the relatively high frequency of this paraneoplastic syndrome [26].

- The NAB2::STAT6 gene fusion is definitively diagnostic; however, its detection by molecular methods is challenging because of the close proximity of the genes on chromosome 12q and the heterogeneity of the fusion breakpoints. Thus, STAT6 immunohistochemistry demonstrating strong, diffuse nuclear staining, serves as a sensitive and specific surrogate marker for all fusion variants and is widely used in routine diagnostic practice [23,25,82].

MOLECULAR CHARACTERISTICS

- Macroscopic features

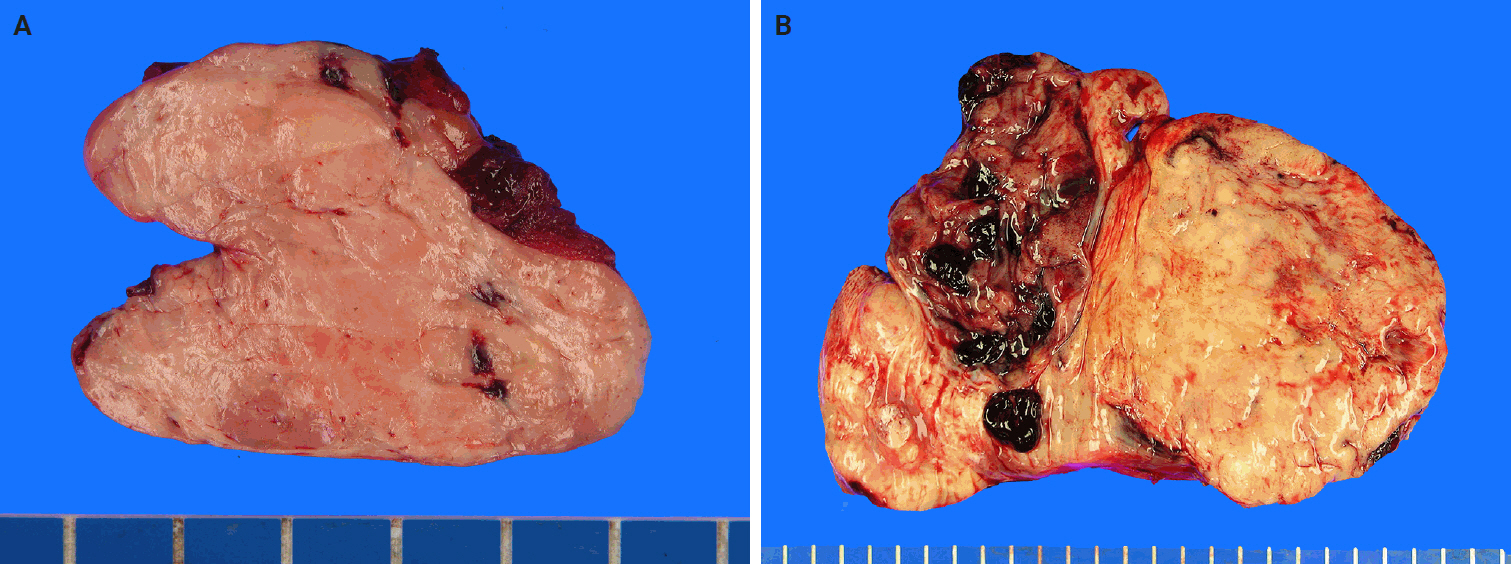

- SFTs are usually well-circumscribed, solid masses ranging in size from 1 cm to greater than 25 cm, with most measuring between 5−10 cm in diameter [83,84]. The cut surface varies from firm and white in more fibrous tumors to tan and fleshy in highly cellular lesions (Fig. 2). Hemorrhage, calcification, or necrosis may occur, particularly in the larger tumors [85-88]. Benign SFTs are typically well-circumscribed, but unencapsulated, whereas malignant tumors often exhibit infiltrative borders and areas of necrosis [89].

- Tumors arising from serosal surfaces often exhibit an exophytic appearance, whereas those within body cavities may be present as polypoid, stalk-attached fibrous masses [3]. Pleural SFTs are often large (>10 cm) and pedunculated, with a pedicle containing prominent feeder vessels. Some cases lack direct pleural attachment and can appear enclosed within the lung parenchyma [37].

- In the CNS, SFTs are usually dural-based, well-circumscribed, firm, white to reddish-brown masses; however, they may occasionally exhibit infiltrative growth or lack dural attachment [90-92]. In the head and neck region, tumor size varies by anatomical site, including approximately 2.5 cm in the larynx, 4 cm in the salivary glands, and 5 cm in the sinonasal tract [46,52,53,89].

- Histopathology

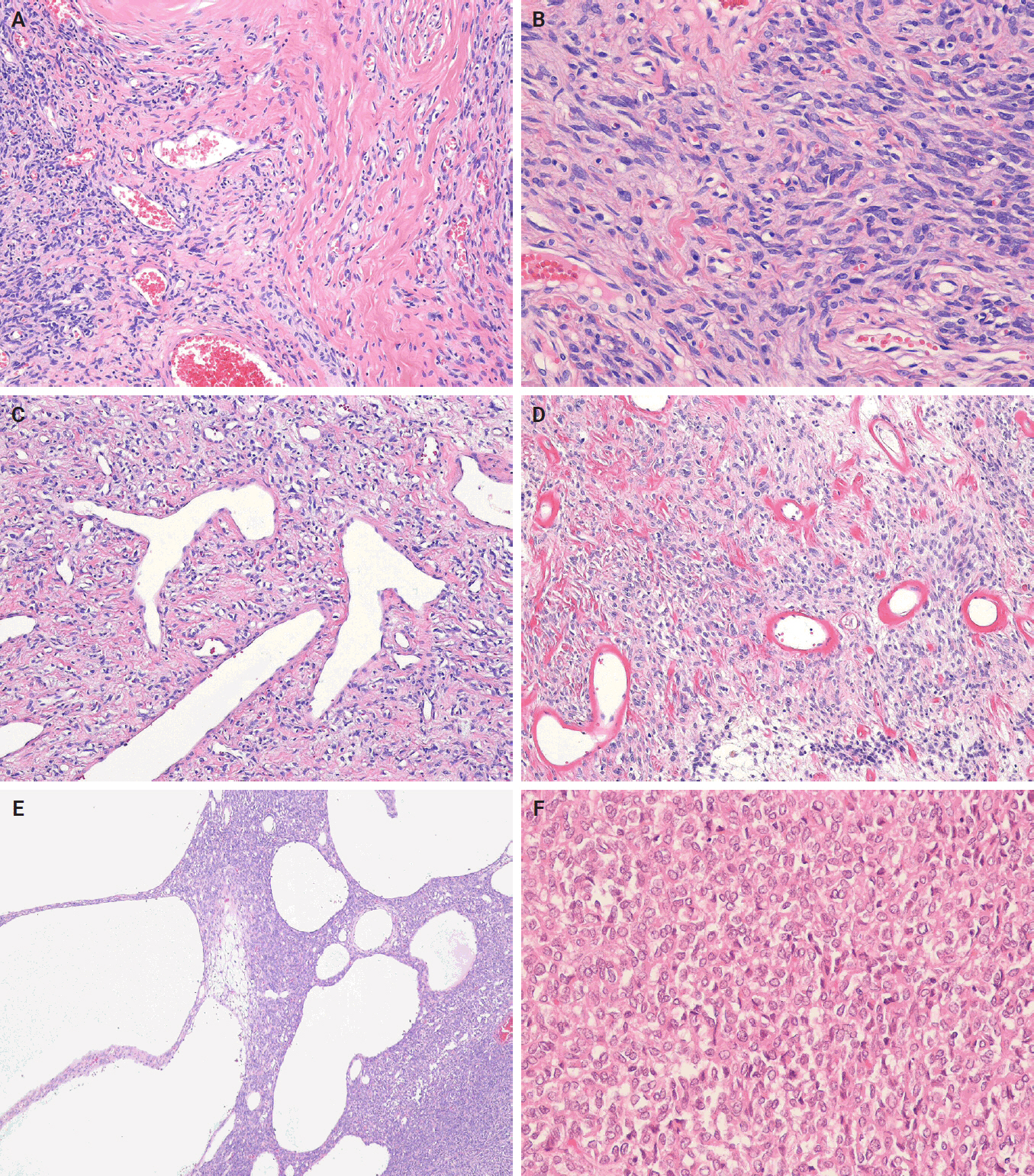

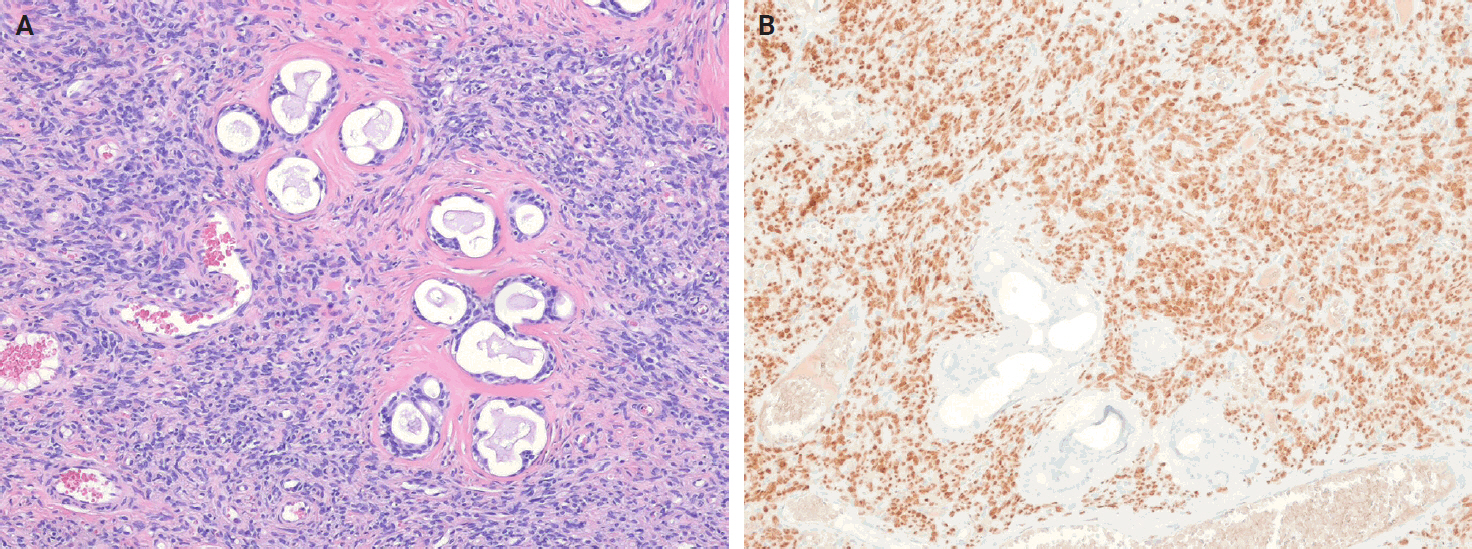

- Histologically, classic SFTs display the so-called patternless pattern, characterized by alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas, with tumor cells frequently interposed between collagen bundles (Fig. 3A). The tumor cells are ovoid to spindle-shaped, with vesicular nuclei, pale eosinophilic cytoplasm, and indistinct cell borders, and are embedded in a variably collagenous stroma (Fig. 3B). A characteristic feature is the presence of thin-walled, branching, staghorn-shaped vessels (Fig. 3C). Perivascular hyalinization may also be observed (Fig. 3D). The degree of cellularity varies considerably, ranging from sparsely scattered individual cells or linear clusters to highly cellular areas, even within the same tumor. The tumor cells are haphazardly arranged within the stroma, often in a storiform configuration or as randomly oriented fascicles. Mitoses are typically infrequent, and significant nuclear pleomorphism or necrosis is absent in conventional cases. Additional histological features may include multinucleated giant cells, myxoid or cystic changes, and hemorrhage (Fig. 3E). Rarely, the foci of epithelioid or rhabdoid tumor cells may also be present (Fig. 3F).

- Subtypes of solitary fibrous tumor

- SFT subtypes share clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical characteristics that support their close relationship.

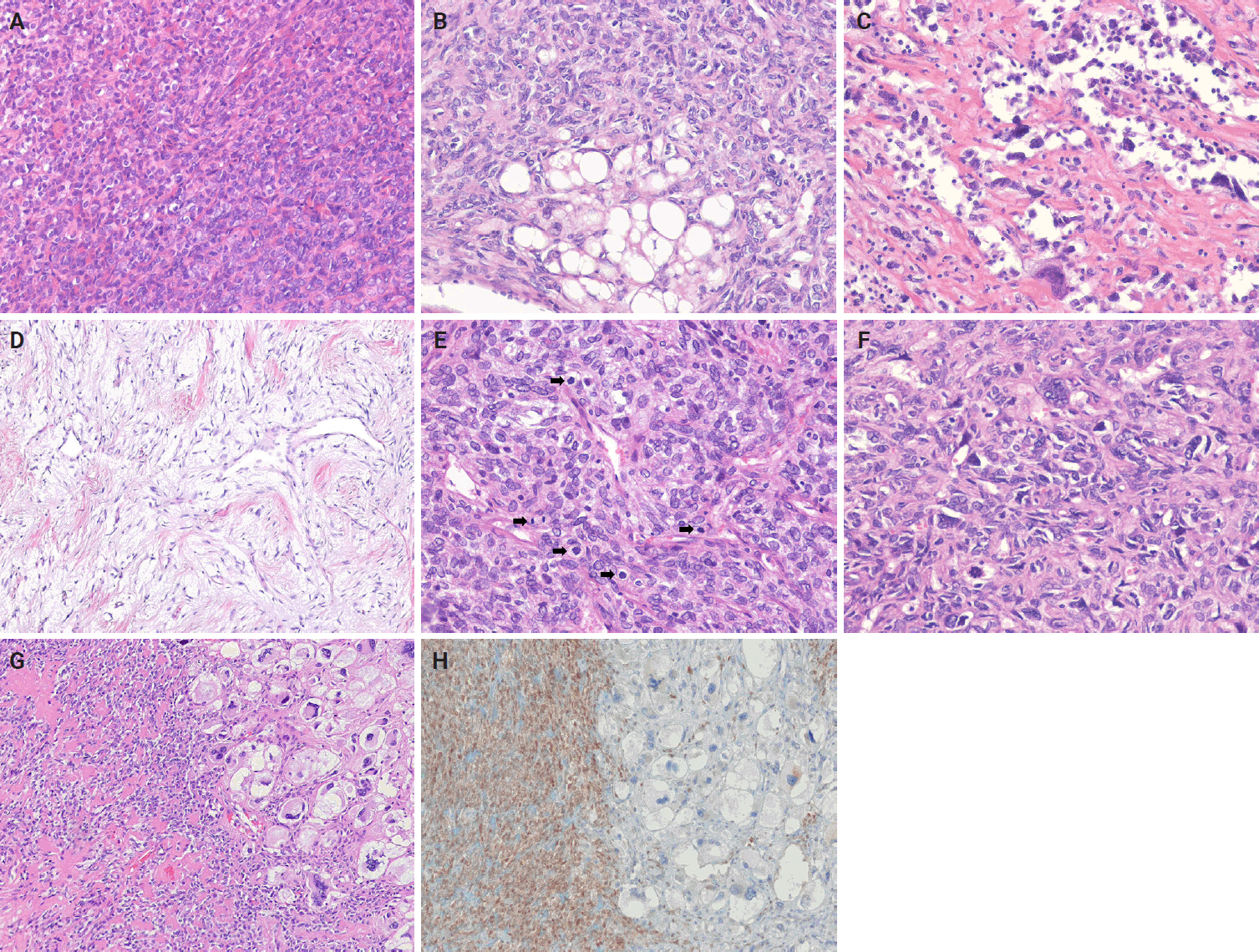

- Cellular SFT is characterized by densely packed tumor cells with indistinct cytoplasmic borders and prominent thin‑walled, branching staghorn-shaped vessels, with little or no intervening stroma. This subtype corresponds to the originally described hemangiopericytoma. The tumor cells are typically monotonous, showing loss of spindled morphology and transition to a more ovoid or rounded shape (Fig. 4A). Hemorrhage is common in cellular SFT, whereas necrosis may also be present.

- Lipomatous (fat-forming) SFT is a rare histological subtype characterized by mature adipose tissue forming an integral component of the tumor. Histologically, it displays the typical features of SFT mixed with a variable amount of mature fat (Fig. 4B) [35,93-95]. An immature lipoblastic component may also be present. Although the majority of lipomatous SFTs are benign, cases with malignant histological features have also been reported [96].

- Giant cell-rich SFT (formerly known as giant cell angiofibroma) is a rare SFT subtype that retains the typical morphological features of conventional SFT, but contains a mixed population of multinucleated giant cells scattered within the stroma and lining pseudovascular spaces [97,98]. The tumor is composed of bland, round-to-spindle cells and multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 4C). It exhibits alternating hypocellular/sclerotic and hypercellular areas, often associated with staghorn-shaped vasculature.

- Focal myxoid change is a common finding in SFTs and may result from an increase in mucin production by neoplastic cells within the connective tissue. Myxoid SFT is a rare SFT subtype characterized by diffuse and prominent myxoid changes involving most of the tumor and exhibit a hypocellular, bland histological appearance (Fig. 4D) [99].

- Malignant SFT is defined by one or more adverse histological features, including hypercellularity, increased mitotic activity (>4 mitoses per 10 high-power fields [HPFs]), cytological atypia, tumor necrosis, and/or infiltrative margins (Fig. 4E, F) [84,100,101]. Of these, a high mitotic count is considered the most reliable predictor of aggressive behavior and poor clinical outcome [30,102]. In accordance with the College of American Pathologists (CAP) and WHO guidelines, it is currently recommended that mitotic activity be reported as the number of mitoses per mm². With older models of microscopes, 10 HPFs are equivalent to 1 mm². With a modern microscope featuring a 0.5 mm field diameter, 5 HPFs correspond to an area of approximately 1 mm². Risk-stratification models, such as that of Demicco et al. [103], integrate clinical and pathological parameters to improve prognostic accuracy.

- Dedifferentiated SFT accounts for less than 1% of all cases and is characterized by an abrupt transition from conventional SFT morphology to high-grade spindle or pleomorphic sarcoma features (Fig. 4G, H) [104-112]. It may occur in various anatomical sites, including the meninges and orbit. Heterologous elements, such as rhabdomyosarcoma or osteosarcoma, have also been described. Dedifferentiated SFT has a high risk of recurrence and metastasis and portends a poor prognosis.

HISTOPATHOLOGICAL FEATURES

Cellular solitary fibrous tumor

Lipomatous (fat-forming) solitary fibrous tumor

Giant cell-rich solitary fibrous tumor

Myxoid solitary fibrous tumor

Malignant solitary fibrous tumor

Dedifferentiated solitary fibrous tumor

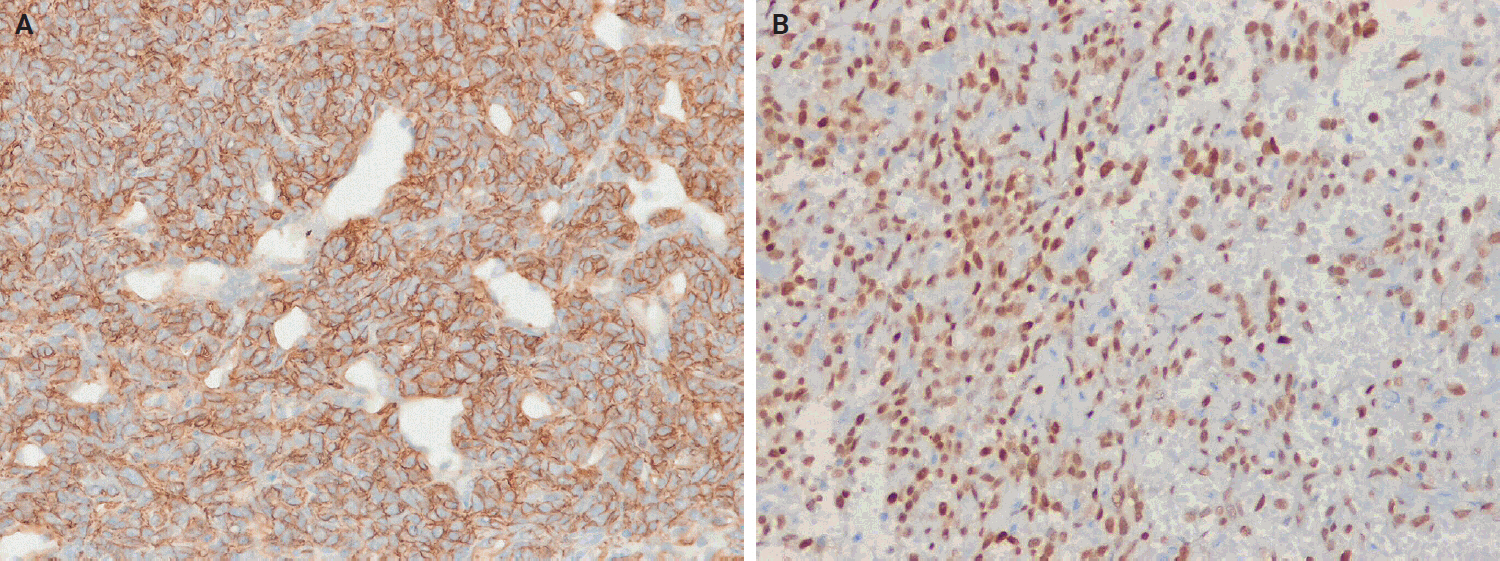

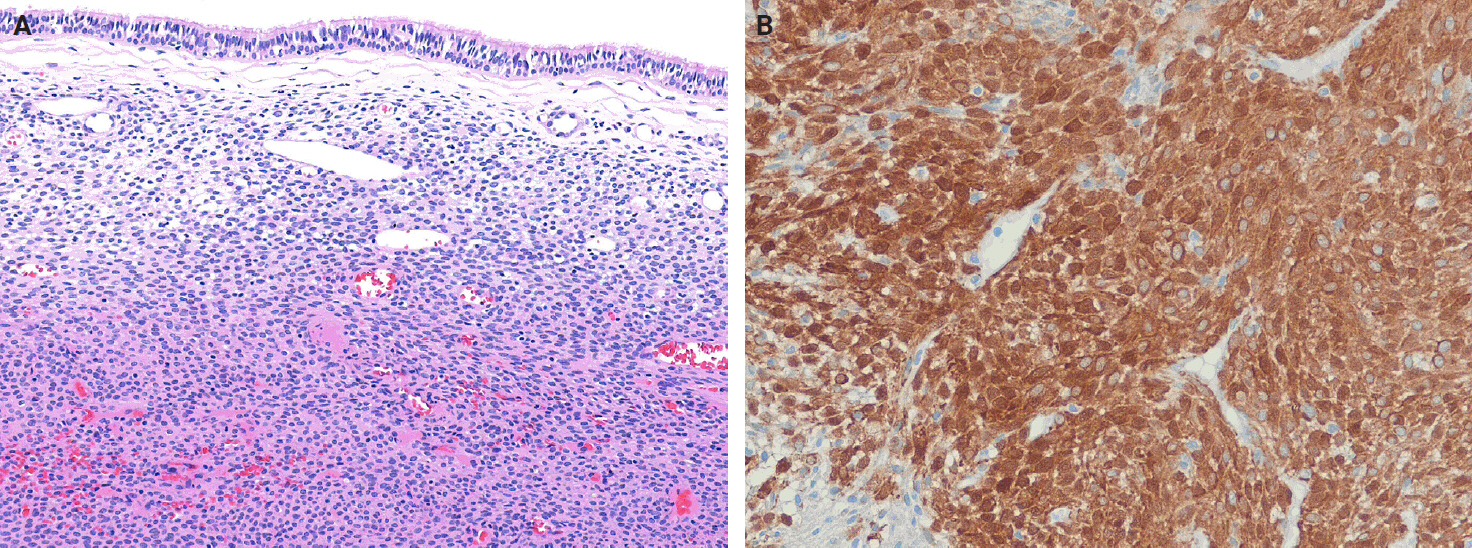

- Immunohistochemical studies have shown that SFTs typically exhibit strong, diffuse nuclear expression of STAT6 and CD34 (Fig. 5) [23,25,73,84,113]. The nuclear localization of STAT6 reflects the presence of the NAB2::STAT6 fusion and serves as a sensitive and specific diagnostic marker that distinguishes SFT from histological mimics [114-117]. However, STAT6 expression has also been reported in dedifferentiated liposarcoma (DDLPS) [118] and GLI1-altered soft tissue tumor [119]. CD34 is expressed in approximately 81%–95% of cases, particularly in low-grade tumors; however, its expression may be decreased or lost in high-grade or dedifferentiated SFTs [120-123]. Similarly, loss of STAT6 expression has been observed in dedifferentiated or embolized tumors [121].

- Gene expression profiling identified other markers that can distinguish SFTs from their histological mimics. Among these, glutamate ionotropic receptor AMPA type subunit 2 (GRIA2) shows 80%–93% sensitivity for SFT [124]. Cytoplasmic aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) demonstrates 84% sensitivity and 99% specificity in differentiating SFT from meningioma and synovial sarcoma (SS) [125]. Subsequent studies indicate that ALDH1 sensitivity ranges from 76% to 97% and GRIA2 sensitivity ranges from 64% to 84%, with GRIA2 exhibiting lower specificity compared with ALDH1 and STAT6 [111,112,126].

- Other immunohistochemical markers, such as BCL2 and CD99, are frequently positive. Epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and smooth muscle actin (SMA) show variable expression, whereas desmin, S100 protein, SOX10, actins, cytokeratins, and the progesterone receptor are typically negative or only focally expressed [83,127,128]. Transducin-like enhancer of split 1 (TLE1) may show weak positivity [129]. Occasional PAX8 expression has also been reported, which may cause diagnostic confusion with renal cell carcinoma [130]. Table 2 summarizes the immunohistochemistry profiles for SFT.

IMMUNOHISTOCHEMICAL FEATURES

- A systematic and integrated approach is required to accurately diagnose SFTs. The process begins with a thorough histopathological evaluation of hematoxylin and eosin sections, particularly at low magnification, to assess tumor borders, cellular uniformity, and overall architecture. Key histological features include bland spindle cell morphology, patternless or short fascicular architecture, and stromal characteristics, such as hyalinization, myxoid change, and the distinctive staghorn-shaped vascular pattern. Recognizing these features is critical for distinguishing SFTs from other spindle cell neoplasms with overlapping morphologies.

- The clinical context, including patient age, tumor location, and symptomatology, together with radiological findings, provides valuable complementary information. For example, a well-circumscribed, hypervascular mass on imaging in a middle-aged or older adult supports the presumptive diagnosis of SFT. These clinical-radiological correlations are particularly helpful when histological findings are equivocal.

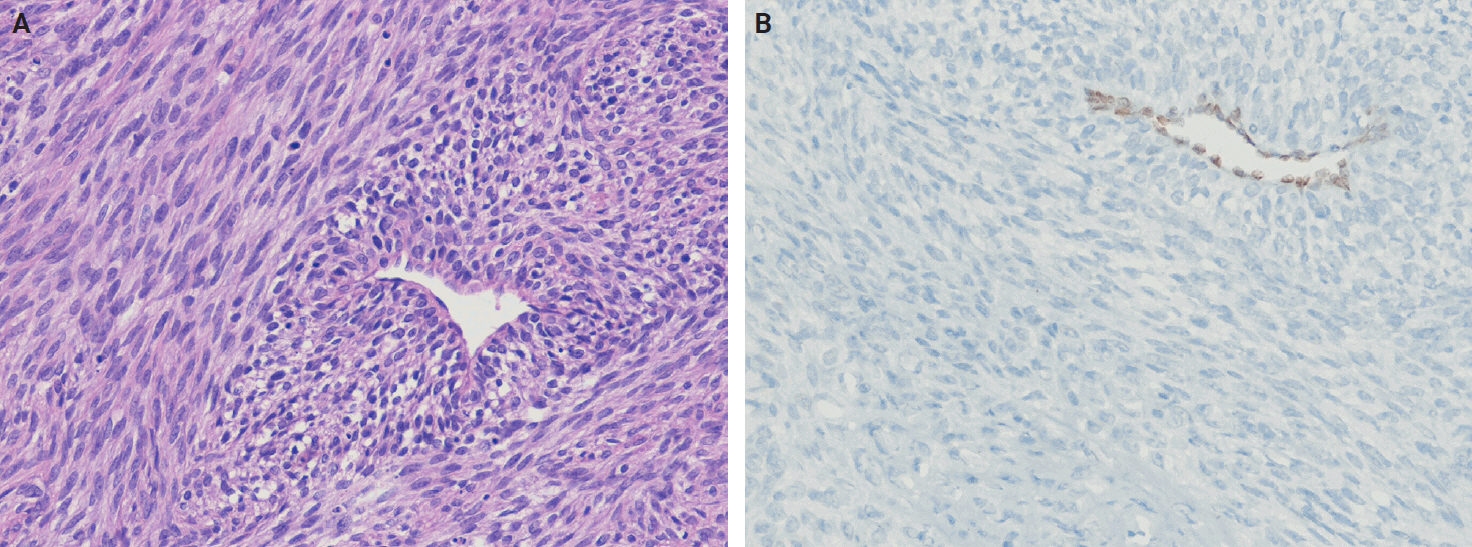

- Immunohistochemistry plays an essential role in the diagnostic algorithm and has largely replaced electron microscopy due to its accessibility and diagnostic utility. It is necessary not only for establishing the line of differentiation but also for identifying molecular surrogates of specific genetic alterations. For SFTs, strong, diffuse nuclear STAT6 expression, which serves as a surrogate marker for the NAB2::STAT6 gene fusion, together with CD34 positivity, constitutes a highly sensitive and specific marker combination. These two markers are routinely used and are generally sufficient to confirm an SFT diagnosis in most cases. However, they are not entirely specific, as focal STAT6 expression may also occur in other mesenchymal tumors, creating potential diagnostic pitfalls. Moreover, additional diagnostic confusion may arise, particularly in tumors occurring in visceral organs, such as the lung, salivary gland, or prostate [32,131]. For example, entrapment of normal glandular epithelium should not be misinterpreted as a biphasic neoplasm, such as phyllodes tumor, pleomorphic adenoma, or sarcomatoid carcinoma (Fig. 6). If STAT6 is negative, second-line antibodies, such as GRIA2 and ALDH1, may be used.

- For diagnostically challenging or histologically atypical cases, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or next-generation sequencing may provide additional diagnostic clarity. These approaches are also helpful for detecting fusion genes or mutations associated with dedifferentiation. They have been incorporated into routine diagnostic workflows to enhance diagnostic precision and enable prognostic stratification, particularly in high-grade or dedifferentiated subtypes. In summary, a comprehensive diagnostic approach that integrates morphologic, immunophenotypic, clinical, and molecular data is essential for achieving diagnostic accuracy, refining risk stratification, and guiding appropriate patient management.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

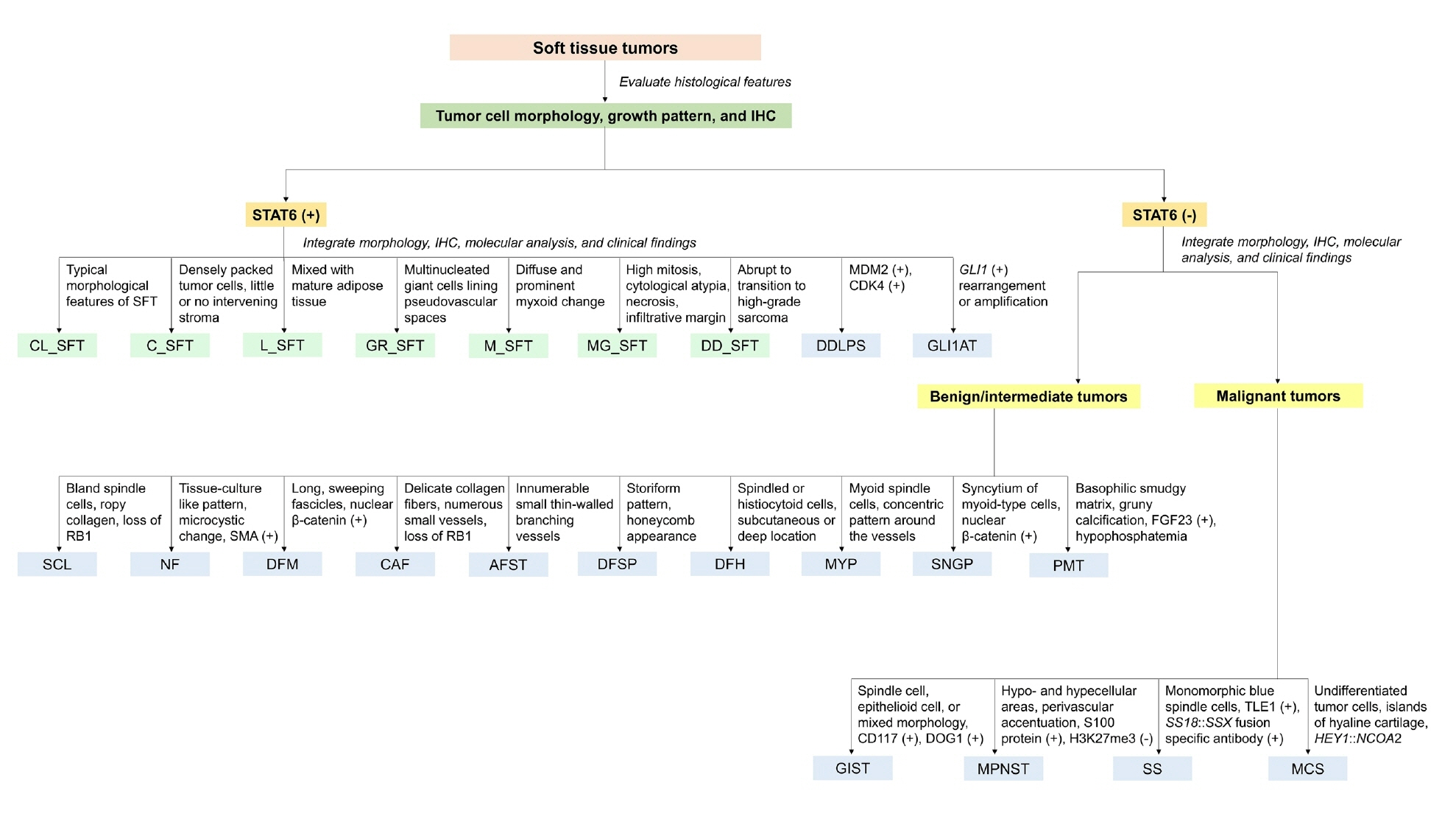

- The histological differential diagnosis of SFT depends on the location and morphology of the tumor; however, it may be substantially improved by immunohistochemical detection of nuclear STAT6 expression. Accurate diagnosis requires a combination of clinical context, anatomic site, histopathological features, and a focused immunohistochemical panel.

- Spindle cell lipoma

- Spindle cell lipoma (SCL) is a benign adipocytic tumor consisting of variable amounts of mature adipocytes, bland spindle cells, and ropy collagen [132]. It occurs most commonly in men aged 45–60 years and typically arises in the subcutaneous tissue of the posterior neck, back, and shoulders. SCL is histologically characterized by bland spindle cells arranged in small, aligned clusters within a myxoid matrix, accompanied by mature adipose tissue and ropy collagen. The spindle cells are typically CD34-positive [133,134] and show loss of nuclear RB1 protein expression [135]. SFTs with hyalinized stroma and admixed adipose tissue may resemble SCL; however, SCLs rarely exhibit a staghorn-shaped vasculature and lack nuclear STAT6 expression.

- Nodular fasciitis

- Nodular fasciitis (NF) is a benign, self-limited fibroblastic/myofibroblastic neoplasm that frequently exhibits a recurrent USP6 rearrangement [136]. It is usually found in the subcutaneous tissue of the extremities and is typically <3 cm in size. NF is relatively common and can present at any age, although it most frequently occurs in young adults. Histologically, NF consists of plump, uniform fibroblasts and myofibroblasts arranged in a tissue culture-like pattern, within a variably myxoid stroma that often contains microcystic changes and extravasated erythrocytes. The tumor cells are positive for SMA and muscle-specific actin (MSA), with occasional desmin expression, but consistently negative for STAT6. The identification of a USP6 rearrangement can assist in diagnostically challenging cases [137-139].

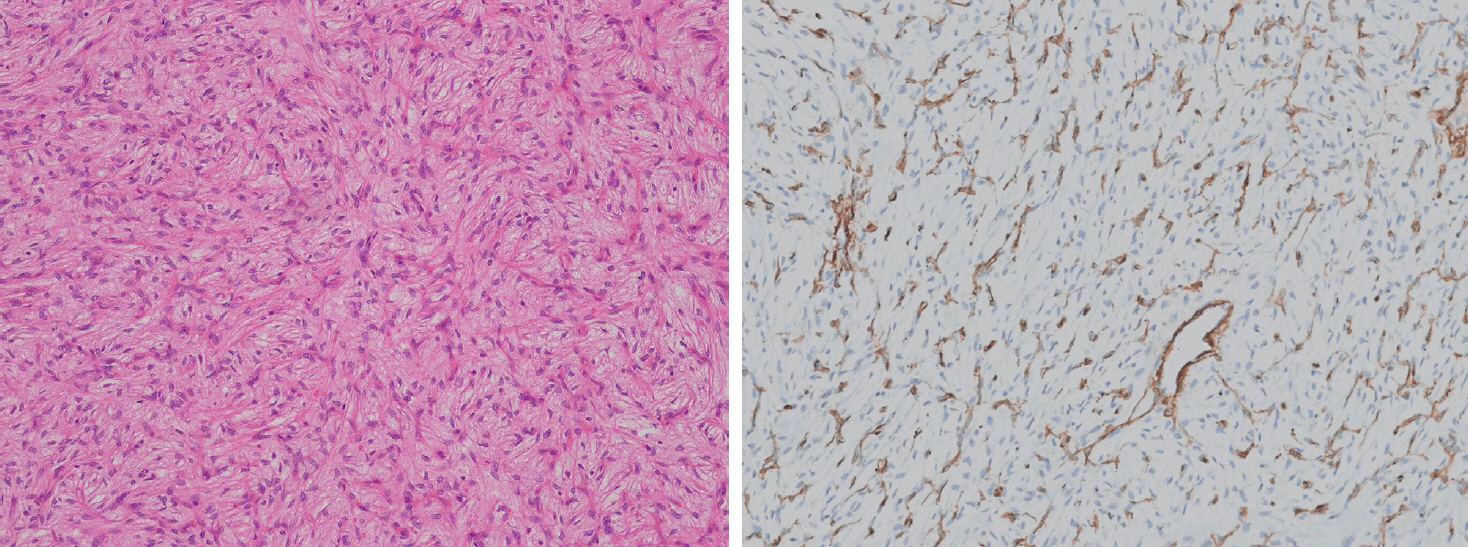

- Desmoid fibromatosis

- Desmoid fibromatosis (DFM) is a locally aggressive, non-metastasizing myofibroblastic neoplasm that is characterized by infiltrative growth and a high propensity for local recurrence [140]. It frequently arises in the extremities, abdominal cavity, retroperitoneum, abdominal wall, and chest wall, and predominantly affects young female adults, with a median age of 37–39 years. DFM is driven by somatic CTNNB1 mutations or inactivating germline APC mutations [141-144]. Histologically, it consists of uniform fibroblastic cells arranged in long, sweeping fascicles with collagen deposition. Small-caliber vessels with perivascular edema are also present. Immunohistochemically, DFM is positive for SMA and MSA, and nuclear β-catenin expression is observed in most cases. STAT6 negativity helps distinguish DFM from SFT.

- Cellular angiofibroma

- Cellular angiofibroma (CAF) is a benign, cellular, and richly vascular fibroblastic neoplasm that typically arises in the vulvar or inguinoscrotal region [145]. It affects both sexes with a similar frequency, with peak incidence in women during the fifth decade and in men during the seventh decade. Loss of 13q14, including RB1, is a characteristic genetic alterations in CAFs [146,147]. Histologically, it consists of bland spindle cells arranged in short fascicles among delicate collagen fibers, accompanied by numerous small- to medium-sized thick-walled vessels, and may contain intermixed adipose tissue. Immunohistochemically, CD34 is expressed in 30%–60% of cases, whereas SMA and desmin are variably expressed in a minority of cases [145,148]. Loss of nuclear RB1 expression is frequently observed. CAF can mimic SFT morphologically; however, the vessels are generally smaller, more hyalinized, and fibrotic. STAT6 expression is consistently negative.

- Angiofibroma of soft tissue

- Angiofibroma of soft tissue (AFST) is a benign fibroblastic neoplasm characterized by a prominent, arborizing network of numerous branching, thin-walled blood vessels [149]. It primarily affects middle-aged adults, with a peak incidence in the sixth decade of life [150-152]. AFSTs typically arise in the extremities, particularly the legs. A recurrent t(5;8)(p15;q13) translocation, resulting in an AHRR::NCOA2 gene fusion, occurs in approximately 60%–80% of cases [151-153]. Histologically, AFST is composed of bland, uniform short spindle cells embedded in a variable myxoid or collagenous stroma with innumerable small, thin-walled, branching blood vessels (Fig. 7). Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells variably express EMA and CD34, whereas desmin positivity may be observed in scattered dendritic cells [150,152]. AFST often exhibits morphologic overlap with SFT; however, STAT6 expression is consistently absent.

- Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

- Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a superficial, locally aggressive fibroblastic neoplasm. It is characterized by a storiform arrangement of uniform spindle cells and is typically associated with a COL1A1::PDGFB or related gene [154]. DFSP usually occurs on the trunk and proximal extremities, followed by the head and neck region. It predominantly affects young to middle-aged adults with a slight male predominance. Histologically, DFSP shows diffusely infiltrative growth into surrounding tissues, often producing a characteristic honeycomb pattern within the subcutaneous fat. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells are diffusely positive for CD34 and negative for STAT6. In contrast, SFTs are usually well-circumscribed and show nuclear STAT6 expression, which serves as a distinguishing feature.

- Deep fibrous histiocytoma

- Deep fibrous histiocytoma (DFH) is a benign morphological variant of fibrous histiocytoma that arises entirely within the subcutaneous or deep soft tissue [155]. It occurs over a wide age range (6–84 years old, with a median age of 37 years) with a slight male predominance. The extremities are the most commonly affected sites, followed by the head and neck region. Approximately 10% of cases occur in visceral soft tissues, such as the retroperitoneum, mediastinum, and pelvis [156]. Rearrangements of either PRKCB or PRKCD have been identified [157,158]. Histologically, DFH is a well‑circumscribed lesion that exhibits monomorphic spindle‑shaped or histiocytoid cells arranged in a mixed fascicular and storiform pattern, which is often accompanied by prominent branching vessels. Approximately 40% of DFHs express CD34 [156]. These cases may be challenging to distinguish from SFTs; however, they are characteristically negative for STAT6.

- Myopericytoma

- Myopericytoma is a distinctive perivascular myoid neoplasm that forms part of a morphological spectrum with myofibroma [159]. It occurs at any age but is most commonly observed in adults. It usually involves the distal extremities, followed by the proximal extremities, neck, trunk, and oral cavity. Mutations in the PDGFRB gene may underlie a shared pathogenesis among myopericytoma, myopericytomatosis, and myofibroma [160,161]. In addition, cellular or atypical myofibromas are associated with SRF::RELA gene fusions [162]. Histologically, myopericytoma consists of bland, myoid-appearing spindled cells arranged in a concentric perivascular pattern around numerous small vessels (Fig. 8A). Immunohistochemically, myopericytomas express SMA and caldesmon, with focal positivity for desmin and/or CD34 (Fig. 8B). In contrast, SFTs do not show concentric perivascular architecture but instead demonstrate diffuse CD34 and STAT6 positivity.

- Sinonasal glomangiopericytoma

- Sinonasal glomangiopericytoma is a distinctive soft tissue tumor of the sinonasal tract characterized by perivascular myoid differentiation [163]. It occurs at any age, but most commonly presents in the sixth or seventh decade of life, with a slight female predilection. Unilateral involvement of the nasal cavity, particularly the turbinates and septum, is typical, whereas bilateral disease is rare and occurs in fewer than 5% of cases. Molecular alterations include recurrent missense mutations in exon 3 of CTNNB1. Histologically, the tumor appears as an ovoid to spindled syncytium of myoid-type cells within a richly vascularized stroma (Fig. 9A). Perivascular hyalinization with extravasated erythrocytes, mast cells, and eosinophils is commonly observed. The tumor cells exhibit strong SMA and nuclear β-catenin expression, with variable CD34 positivity (Fig. 9B) [164,165]. In contrast, SFTs are positive for CD34 and STAT6, but negative for SMA.

- Dedifferentiated liposarcoma

- DDLPS arises through progression from an atypical lipomatous tumor (ALT) or well-differentiated liposarcoma (WDLPS) into a non-lipogenic sarcoma of variable histologic grade [166]. It most frequently occurs in the retroperitoneum, followed by the spermatic cord and, more rarely, the mediastinum, head and neck, and trunk. DDLPS predominantly affects middle-aged adults, with a peak incidence in the fourth to fifth decade of life, and show no significant sex predilection. Approximately 90% of cases develop de novo, whereas about 10% arise from recurrent ALT/WDLPS [167]. DDLPS shares molecular features with ALT/WDLPS, as both harbor amplification of MDM2 (mouse double minute 2 homolog) and CDK4 (cyclin-dependent kinase 4) on chromosome 12q14-q15 [168,169]. Histologically, DDLPS shows an abrupt or gradual transition from a WDLPS to a spindle cell or pleomorphic non-lipogenic tumor (rarely lipogenic), which may be low or high grade. Immunohistochemically, nuclear positivity for MDM2 and CDK4 is observed in most cases. Lipomatous SFTs may be mistaken for WDLPS or DDLPS because of their fat-containing appearance, particularly in limited biopsy samples or imaging studies. Rarely, DDLPS may display an SFT‑like morphology and even show STAT6 positivity [118], whereas SFTs are typically negative for MDM2 and CDK4. Myxoid SFT may resemble myxoid liposarcoma; however, DDIT3 FISH is negative, and STAT6 expression is diffusely positive in SFTs.

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are mesenchymal neoplasms with variable biological behavior and are characterized by differentiation toward the interstitial cells of Cajal [170]. GISTs can occur at any site within the gastrointestinal tract, whereas extragastrointestinal GISTs most commonly develop in the mesentery, omentum, and retroperitoneum. Sporadic GISTs occur at any age, but most cases appear in the sixth decade of life (median age, 60 to 65 years), with a slight male predominance [171]. Most GISTs have activating mutations in KIT or PDGFRA. Histologically, GISTs display a broad morphological spectrum and typically consist of relatively monomorphic spindle cells, epithelioid cells, or a mixture of both. Immunohistochemically, GISTs positively express CD34, CD117 (KIT), and DOG1. They may closely resemble SFTs, but can be distinguished by their positive CD117 (KIT) and DOG1 expression, and negative STAT6 expression.

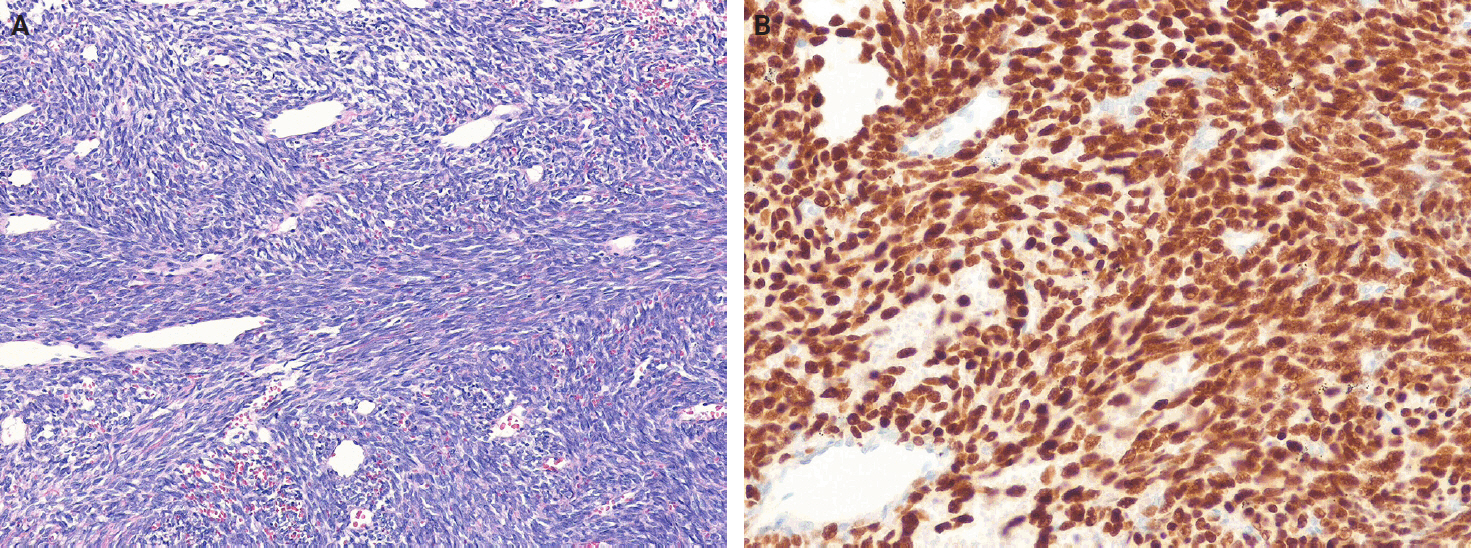

- Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

- Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) is a malignant spindle cell neoplasm with Schwannian differentiation [172]. It most commonly arises in older adults during the seventh decade of life, although it can occur across a wide age range [173]. Approximately 50% of cases occur in association with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), 10% are associated with prior radiation exposure, and the remainder are sporadic [174]. MPNST most frequently involves the trunk and extremities, followed by the head and neck region. At the molecular level, MPNSTs exhibit complex structural and numerical chromosomal abnormalities, and biallelic inactivation of the NF1 gene is commonly observed in MPNST [175,176]. Histologically, conventional MPNST displays fascicular growth of relatively uniform spindle cells, alternating hypercellular and hypocellular areas, perivascular accentuation, and geographical necrosis (Fig. 10A). The tumor cells show focal positivity for S100 protein and SOX10 expression, along with loss of H3K27me3 expression (Fig. 10B) [177]. MPNST may resemble cellular SFT; however, it is usually negative for CD34 and STAT6, while showing focal expression of S100 protein and SOX10.

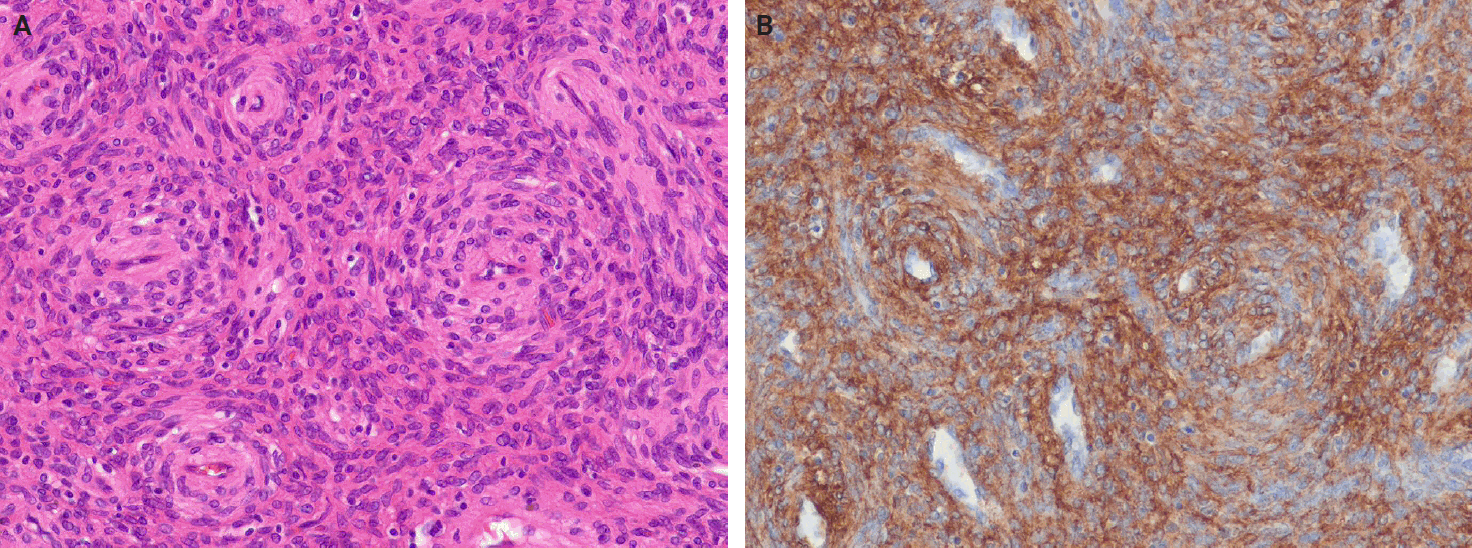

- Synovial sarcoma

- SS is a monomorphic spindle cell sarcoma with variable epithelial differentiation. It is defined by SS18::SSX1, SS18::SSX2, or SS18::SSX4 gene fusions [178]. Approximately 70% of the cases occur in the deep soft tissue of the extremities, often near joints, with 15% in the trunk and 7% in the head and neck. SS can occur at any age, with no sex predilection, although half of the patients are adolescents or young adults [179]. Histologically, SS may be classified into three subtypes: monophasic (dense fascicles of monomorphic spindle cells with staghorn-shaped vasculature), biphasic (containing epithelial and spindle components), and poorly differentiated (high cellularity, nuclear atypia, and brisk mitotic activity) (Fig. 11A) [180]. TLE1 shows nuclear positivity in up to 95% of cases, with patchy to focal cytokeratin and EMA staining. SS18::SSX fusion–specific and SSX-specific C-terminal antibodies have recently been developed that yield strong, diffuse nuclear staining with >95% sensitivity and specificity (Fig. 11B) [181]. Cellular SFT can mimic SS; however, SSs are typically negative for CD34 and STAT6.

- Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor

- Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors (PMTs) are morphologically distinct neoplasms that cause tumor-induced osteomalacia, most often through overproduction of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) [182]. PMTs may arise in almost any soft tissue or bone, but are uncommon in the retroperitoneum, viscera, and mediastinum. They frequently affect middle‑aged adults with no sex predilection, although they can also develop in pediatric and elderly patients. Approximately half of all PMTs harbor FN1::FGFR1 fusions and, rarely, FN1::FGF1 fusions [183,184]. Histologically, PMT consists of bland spindle-shaped cells with characteristic grungy calcification and a prominent capillary network, with occasional staghorn-shaped vessels. PMT exhibits variable ERG, SATB2, and CD56 expression. FGF23 expression has been reported in some cases, but currently available antibodies lack specificity, which limits their diagnostic utility [185,186]. PMTs may mimic SFTs; however, SFTs lack the grungy calcified matrix typical of PMTs and usually show CD34 and STAT6 positivity.

- Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma

- Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma (MCS) is a high‑grade malignant tumor with a distinct biphasic pattern. It consists of primitive undifferentiated mesenchymal cells and well‑differentiated hyaline cartilage [187]. MCS most commonly arises in the second or third decade of life, with a median age of approximately 30 years and a slight male predominance. MCS exhibits a broad anatomical distribution, involving bone, soft tissue, and intracranial locations. Approximately 40% of cases occur in somatic soft tissues, and the meninges are a common extra-skeletal site [188]. At a molecular level, MCS harbors a specific and recurrent HEY1::NCOA2 fusion, which has been identified in nearly all cases [189]. Histologically, MCS exhibits undifferentiated tumor cells, cartilage islands, and a staghorn-shaped vascular pattern. The undifferentiated tumor cells often express CD99, SOX9, and NKX2.2 [190], and may occasionally show aberrant expression of desmin, myogenin, and MYOD1. Because the cartilage foci may be scant or absent in limited biopsies, MCS may be mistaken for malignant SFT; however, SFTs are distinguished by nuclear STAT6 positivity, which is absent in MCSs.

- Table 3 provides an overview of the differential diagnosis of SFTs, summarizing the clinical, histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of morphologically similar entities.

- Fig. 12 shows diagnostic algorithm and differential diagnosis of SFT.

HISTOLOGICAL DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

- SFTs exhibit a broad spectrum of clinical behavior, with local or distant recurrence occurring in 10%–30% of cases and, occasionally, >15 years after treatment [30,31,101,191]. To improve prognosis, multivariate risk models have been developed and validated across various anatomical sites. The most commonly used model includes mitotic count, tumor size (≥5 cm), and patient age (≥55 years), with some modifications that also include necrosis as a fourth parameter [31,103,192]. Table 4 presents three-variable and modified four-variable risk models for predicting metastatic risk in SFTs [31,103]. These models are superior to the traditional benign versus malignant classification and may be applied to thoracic, extra-thoracic, and gynecologic SFTs.

- At the molecular level, TERT promoter mutations and TP53 loss are more frequently observed in high-grade or dedifferentiated tumors [77,193]. Positive p53 expression and elevated Ki-67 index (>5%) are associated with poorer prognosis in some studies [54].

- In the CNS, SFTs exhibit higher rates of long-term recurrence and metastasis, even in WHO grade 1 cases. Mitotic activity and necrosis, rather than tumor size or patient age, are the strongest predictors of progression. A three-tiered histologic grading scheme was recommended for CNS SFTs [39,76]. In the head and neck region, most SFTs behave indolently, with recurrence rates <10%; however, ocular adnexal SFTs exhibit a higher local recurrence rate (~25%) with a low metastatic potential (~2%) [46,194]. Positive surgical margins and dedifferentiation are independent risk factors of relapse. If metastasis occurs, it most often involves the lungs, bones, and liver [55].

PROGNOSIS

- The management of SFT should be done in specialized sarcoma centers with a multidisciplinary team experienced in this rare entity [7]. Treatment response is generally assessed using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST); however, because of the hypervascular nature of SFT, some studies also use the Choi criteria, which is defined as a ≥10% decrease in tumor size or a >15% decrease in tumor density [195-197].

- Localized lesions

- Complete en bloc surgical resection with negative margins (R0) is the gold standard for treatment. The 10-year overall survival rate following R0 resection ranges from 54% to 89% [198-200]. If margins are positive (R1/R2), re‑resection should be considered where feasible. Adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) can achieve >80% 5-year local control for high-risk or margin-positive cases, although no survival benefit has been demonstrated [68,201-204]. Preoperative RT may be considered in selected cases to increase resectability; however, there is no proven role for neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy [205-207]. SFTs generally do not respond well to conventional sarcoma regimens. Thus, systemic therapy should be reserved for clinical trials or in very high‑risk situations.

- Advanced or metastatic lesions

- Isolated, resectable metastases (e.g., lung) can be treated with surgery or ablative methods. RT is an option for local control in selected cases. Conventional chemotherapy demonstrates low overall response rates (0%–20%) [208,209]. Anthracycline-based regimens are used as first-line therapy. Ifosfamide, dacarbazine, or trabectedin may be administered in later lines [210-212]. Median progression‑free survival is generally limited to 4–5 months. Because SFTs are highly vascular, antiangiogenic therapy has shown promising results. Pazopanib, sunitinib, sorafenib, and temozolomide plus bevacizumab have achieved partial responses and significant disease control [213-218]. In prospective trials, pazopanib produced partial responses in >50% of patients by Choi criteria, supporting its role as a potential first-line therapy for advanced SFT. IGF-1 is frequently overexpressed in SFTs. Figitumumab, an anti–IGF-1 receptor monoclonal antibody, has shown efficacy in some advanced cases [218,219]. Data on immunotherapy are limited, although anecdotal durable responses have been reported with programmed death-1 inhibitors (e.g., pembrolizumab) [220,221]. Ongoing studies are evaluating combinatorial approaches with immune checkpoint inhibitors and antiangiogenic agents.

TREATMENT

- The current understanding of SFTs is primarily based on retrospective case series and preclinical studies, which limits the generalizability and robustness of existing diagnostic and therapeutic strategies [222]. Consequently, substantial gaps remain in the areas of tumor biology, prognostication, and optimal treatment pathways.

- A critical area of investigation is the prognostic relevance of the specific NAB2::STAT6 gene fusion variants. Although the NAB2::STAT6 fusion is a molecular hallmark of SFTs, its transcript variants and their effects on tumor behavior, metastatic potential, and treatment response remain unclear. Prospective studies integrating molecular and clinicopathological data are essential for developing reliable, fusion-based risk stratification models.

- The development of advanced molecular platforms, such as NGS, offers the ability not only to detect NAB2::STAT6 gene fusions but also to identify additional genetic alterations with prognostic or therapeutic significance. In addition, ongoing research into the immunologic profile of SFTs warrants further study of immune checkpoint inhibitors and other immunotherapeutic strategies.

- Ultimately, progress in SFT management will depend on coordinated efforts to refine molecular classification, improve diagnostic accuracy, and develop targeted therapies tailored to individual patient risk profiles.

- Recent advances in artificial intelligence and digital pathology suggest new opportunities for prognostic assessment in SFTs. By enabling quantitative and reproducible evaluation of histomorphological features, AI-based image analysis may complement existing clinicopathological models. Although data are still limited, future integration of these technologies could enhance risk stratification and individualized patient management.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

- SFT is a rare fibroblastic neoplasm that poses significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Its broad histological spectrum and frequent morphological overlap with other soft tissue tumors make accurate diagnosis difficult, often requiring an integrated approach that combines immunohistochemistry and molecular testing. A comprehensive understanding of SFT, including its histological variants, molecular subtypes, and variable clinical behavior, is essential for optimizing surgical management, identifying patients requiring systemic therapy, and establishing effective long-term surveillance protocols. As the molecular mechanisms underlying SFT are further elucidated, it will be critical to incorporate these advances into clinical practice to enhance diagnostic precision, refine risk stratification, and enable the development of personalized treatment strategies.

CONCLUSION

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

J.H.C., a contributing editor of the Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article.

Funding Statement

No funding to declare.

| Immunostain | Approximate frequency (%) | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Fusion-related marker | ||

| STAT6 | >95 | Strong, diffuse nuclear staining; highly sensitive and specific surrogate for NAB2::STAT6 gene fusion, although rare exceptions have been reported in other tumorsa |

| Markers discovered by gene expression profiling | ||

| ALDH1 | 75–95 | Stem cell marker; not entirely specific |

| GRIA2 | 60–80 | Relatively specific; limited commercial availability |

| TLE1 | <10 | Rarely positive; not diagnostically useful |

| Endothelial marker | ||

| CD34 | 90–95 | Commonly positive; may be lost in dedifferentiated SFT |

| Neuroectodermal marker | ||

| CD99 | ~70 | Nonspecific; also positive in other tumors |

| Muscle markers | ||

| SMA | 20–35 | Nonspecific; focal expression |

| Desmin | <5 | Usually negative |

| Nerve sheath marker | ||

| S100 protein | ~15 | Focal expression; may mimic nerve sheath tumors; potential diagnostic pitfall |

| Epithelial markers | ||

| EMA | 20–35 | Focal expression; potential diagnostic pitfall |

| Cytokeratins | <10 | Rare focal expression; may be confused with carcinoma |

| PAX8 | ~40 | Relatively frequent expression; not a specific marker of SFT; potential diagnostic pitfall |

| Prognostic markers | ||

| p53 | Variable | Aberrant expression associated with malignant/dedifferentiated SFTb |

| p16 | Variable | Overexpression may be associated with aggressive behavior |

| Others | ||

| BCL2 | ~30 | Frequently expressed but nonspecific; limited diagnostic value |

STAT6, signal transducer and activator of transcription 6; ALDH1, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1; GRIA2, glutamate ionotropic receptor AMPA type subunit 2; TLE1, transducin-like enhancer of split 1; SMA, smooth muscle actin; EMA, epithelial membrane antigen; PAX8, paired box gene 8; SFT, solitary fibrous tumor; BCL2, B-cell lymphoma 2.

aSTAT6 is rarely expressed in dedifferentiated liposarcoma and GLI1-altered soft tissue tumor;

bTP53 mutation in approximately 40% of malignant SFTs.

| Tumor type | Clinical feature | Histological feature | Immunohistochemistry | Molecular feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spindle cell lipoma | Men aged 45–60 years; posterior neck, back, shoulders | Bland spindle cells, mature adipose tissue, myxoid stroma, ropy collagen | CD34 (+); loss of RB1 protein expression | Loss of chromosome 13q14, including RB1 |

| Nodular fasciitis | Young adults; subcutaneous tissue of extremities; usually <3 cm in size | Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in tissue culture-like growth pattern, myxoid, microcystic changes | SMA (+), often diffuse; desmin (±) | USP6 rearrangement |

| Desmoid fibromatosis | Young to middle-aged adult; female predominance; abdominal wall, extremities, mesentery | Uniform fibroblasts arranged in long sweeping fascicles, collagen deposition | SMA (+); desmin (±); nuclear β-catenin (+) in the majority of cases | Somatic mutations in CTNNB1; inactivating germline mutations in APC |

| Cellular angiofibroma | Women (5th decade) and men (7th decade); vulvar and inguinoscrotal sites | Bland spindle cells with delicate collagen fibers, small- to medium-sized thick-walled vessels | CD34 (+); SMA (±); desmin (±); loss of RB1 protein expression | Loss of chromosome 13q14, including RB1 |

| Angiofibroma of soft tissue | Middle-aged adults (6th decade); extremities, most commonly legs | Bland spindle cells in myxoid or collagenous stroma with small thin-walled branching blood vessels | SMA (+); desmin (±) | t(5;8)(p15;q13); AHRR::NCOA2 |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans | Young to middle-aged adults; trunk, proximal extremities, head and neck region | Uniform spindle cells arranged in a storiform pattern with fat infiltration showing a honeycomb pattern | CD34 (+) | COL1A1::PDGFB |

| Deep fibrous histiocytoma | Broad age range (median 37 years); most commonly subcutaneous; extremities, head and neck | Monomorphic spindle or histiocytoid cells in storiform or fascicular pattern | CD34 (+) in approximately 40% of cases | PRKCB or PRKCD rearrangements |

| Myopericytoma | Any age, most often adults; extremities, neck, trunk, oral cavity | Bland, myoid-appearing spindle cells in a concentric perivascular growth pattern | SMA (+); caldesmon (+); desmin (±); CD34 (±) | PDGFRB mutations; SRF::RELA (cellular/atypical myofibromas) |

| Sinonasal glomangiopericytoma | Any age, most common in adults; sinonasal tract, particularly turbinate and septum | Ovoid to spindle cells, syncytial arrangement, thin-walled staghorn-shaped vessels | SMA (+); nuclear β-catenin (+) | Mutations in CTNNB1 exon 3 |

| Dedifferentiated liposarcoma | Middle-aged adults; retroperitoneum, spermatic cord, mediastinum | Abrupt transition from WDLPS to spindle cell or pleomorphic non-lipogenic sarcoma | MDM2 (+); CDK4 (+) | MDM2 and CDK4 amplification |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | Any age (peak in the 6th decade); gastrointestinal tract, mesentery, omentum | Relatively monomorphic spindle cells, epithelioid cells, or mixture of both | CD117 (+), DOG1 (+); PDGFRA (+)a; loss of SDHB expressionb | KIT or PDGFRA mutations |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | Older adults, but can occur across a wide age range; trunk, extremities, head and neck | Spindle cells arranged in fascicles with alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas, often with necrosis | S100 protein (+)c, SOX10 (+); loss of H3K27me3 expression | Mutations in NF1, CDKN2A/CDKN2B, PRC2 core components (EED or SUZ12) |

| Synovial sarcoma | Adolescents and young adults; extremities, trunk, head and neck | Monophasic (monomorphic spindle cells), biphasic, poorly differentiated patterns | SS18::SSX fusion–specific antibody (+), SSX-specific antibody (+); TLE1 (+) | SS18::SSX1, SS18::SSX2, or SS18::SSX4 |

| Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor | Middle‑aged adults; any site; typically associated with hypophosphatemia and osteomalacia | Bland spindle-shaped cells with grungy calcification and a prominent vascular network | ERG (+); SATB2 (+); CD56 (+); FGF23 (+) | FN1::FGFR1, FN1::FGF |

| Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma | Adolescents and young adults; bone, soft tissue, and meninges | Undifferentiated round tumor cells with islands of cartilage and staghorn-shaped vascular pattern | CD99 (+); SOX9 (+); NKX2.2 (+); desmin (±); myogenin (±) | HEY1::NCOA2 |

+, positive staining; RB1, retinoblastoma 1; SMA, smooth muscle actin; ±, variable staining; WDLPS, well-differentiated liposarcoma; MDM2, mouse double minute 2; CDK4, cyclin-dependent kinase 4; DOG1, discovered on GIST-1; PDGFRA, platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha; SDHB, succinate dehydrogenase subunit B; SOX10, SRY-box transcription factor 10; PRC2, polycomb repressive complex 2; H3K27me3, trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 27; TLE1, transducin-like enhancer of split 1; ERG, ETS-related gene; SATB2, special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2; FGF23, fibroblast growth factor 23; NKX2.2, NK2 homeobox 2.

aPDGFRA-mutant gastrointestinal stromal tumors typically demonstrate strong, diffuse expression of PDGFRA;

bSuccinate dehydrogenase-deficient gastrointestinal stromal tumors show complete loss of SDHB staining;

cS100 protein is focally positive in 50%–60% of cases.

| Risk factor | Cut-off | Points (3-variable model) | Points (4-variable model) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient age (yr) | <55 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥55 | 1 | 1 | |

| Mitoses per mm2 (mitoses per 10 HPFs) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| 0.5−1.5 (1−3) | 1 | 1 | |

| ≥2 (≥4) | 2 | 2 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0−4.9 | 0 | 0 |

| 5−9.9 | 1 | 1 | |

| 10−14.9 | 2 | 2 | |

| ≥15 | 3 | 3 | |

| Tumor necrosis | <10% | N/A | 0 |

| ≥10% | N/A | 1 | |

| Risk category (total points)a | Low risk | 0−2 | 0−3 |

| Intermediate risk | 3−4 | 4−5 | |

| High risk | 5−6 | 6−7 |

- 1. Demicco EG, Han A. Solitary fibrous tumour. In: The WHO Classification Editorial Board, ed. WHO classification of tumours: soft tissue and bone tumours. 5th ed. Lyon: IARC Press, 2020; 104-8.

- 2. Fletcher CD. The evolving classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the new WHO classification. Histopathology 2006; 48: 3-12. ArticlePubMed

- 3. Kallen ME, Hornick JL. The 2020 WHO classification: what's new in soft tissue tumor pathology? Am J Surg Pathol 2021; 45: e1-23. PubMed

- 4. Thway K, Ng W, Noujaim J, Jones RL, Fisher C. The current status of solitary fibrous tumor: diagnostic features, variants, and genetics. Int J Surg Pathol 2016; 24: 281-92. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 5. Martin-Broto J, Mondaza-Hernandez JL, Moura DS, Hindi N. A comprehensive review on solitary fibrous tumor: new insights for new horizons. Cancers (Basel) 2021; 13: 2913.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 6. Bianchi G, Lana D, Gambarotti M, et al. Clinical, histological, and molecular features of solitary fibrous tumor of bone: a single institution retrospective review. Cancers (Basel) 2021; 13: 2470.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. de Bernardi A, Dufresne A, Mishellany F, Blay JY, Ray-Coquard I, Brahmi M. Novel therapeutic options for solitary fibrous tumor: antiangiogenic therapy and beyond. Cancers (Basel) 2022; 14: 1064.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Stout AP, Murray MR. Hemangiopericytoma: a vascular tumor featuring Zimmermann's pericytes. Ann Surg 1942; 116: 26-33. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Stout AP. Hemangiopericytoma: a study of 25 cases. Cancer 1949; 2: 1027-54. ArticlePubMed

- 10. Stout AP. Tumors featuring pericytes: glomus tumor and hemangiopericytoma. Lab Invest 1956; 5: 217-23. PubMed

- 11. Enzinger FM, Smith BH. Hemangiopericytoma: an analysis of 106 cases. Hum Pathol 1976; 7: 61-82. PubMed

- 12. Battifora H. Hemangiopericytoma: ultrastructural study of five cases. Cancer 1973; 31: 1418-32. ArticlePubMed

- 13. Erlandson RA, Woodruff JM. Role of electron microscopy in the evaluation of soft tissue neoplasms, with emphasis on spindle cell and pleomorphic tumors. Hum Pathol 1998; 29: 1372-81. ArticlePubMed

- 14. Dardick I, Hammar SP, Scheithauer BW. Ultrastructural spectrum of hemangiopericytoma: a comparative study of fetal, adult, and neoplastic pericytes. Ultrastruct Pathol 1989; 13: 111-54. ArticlePubMed

- 15. Gengler C, Guillou L. Solitary fibrous tumour and haemangiopericytoma: evolution of a concept. Histopathology 2006; 48: 63-74. ArticlePubMed

- 16. Schurch W, Skalli O, Lagace R, Seemayer TA, Gabbiani G. Intermediate filament proteins and actin isoforms as markers for soft-tissue tumor differentiation and origin. III. Hemangiopericytomas and glomus tumors. Am J Pathol 1990; 136: 771-86. PubMedPMC

- 17. Nemes Z. Differentiation markers in hemangiopericytoma. Cancer 1992; 69: 133-40. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 18. Middleton LP, Duray PH, Merino MJ. The histological spectrum of hemangiopericytoma: application of immunohistochemical analysis including proliferative markers to facilitate diagnosis and predict prognosis. Hum Pathol 1998; 29: 636-40. ArticlePubMed

- 19. D'Amore ES, Manivel JC, Sung JH. Soft-tissue and meningeal hemangiopericytomas: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Hum Pathol 1990; 21: 414-23. ArticlePubMed

- 20. Fletcher CD. Haemangiopericytoma: a dying breed? Reappraisal of an ‘entity’ and its variants: a hypothesis. Curr Diagn Pathol 1994; 1: 19-23. Article

- 21. Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol 1931; 11: 385-412. Article

- 22. England DM, Hochholzer L, McCarthy MJ. Localized benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura: a clinicopathologic review of 223 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1989; 13: 640-58. PubMed

- 23. Doyle LA, Vivero M, Fletcher CD, Mertens F, Hornick JL. Nuclear expression of STAT6 distinguishes solitary fibrous tumor from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol 2014; 27: 390-5. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 24. Barthelmess S, Geddert H, Boltze C, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors/hemangiopericytomas with different variants of the NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion are characterized by specific histomorphology and distinct clinicopathological features. Am J Pathol 2014; 184: 1209-18. ArticlePubMed

- 25. Schweizer L, Koelsche C, Sahm F, et al. Meningeal hemangiopericytoma and solitary fibrous tumors carry the NAB2-STAT6 fusion and can be diagnosed by nuclear expression of STAT6 protein. Acta Neuropathol 2013; 125: 651-8. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 26. Robinson DR, Wu YM, Kalyana-Sundaram S, et al. Identification of recurrent NAB2-STAT6 gene fusions in solitary fibrous tumor by integrative sequencing. Nat Genet 2013; 45: 180-5. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 27. Guillou L, Fletcher JA, Fletcher CD, Mandahl N. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumour and haemangiopericytoma. In: Fletcher CD, Unni KK, Mertens F, eds. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 3rd ed. Lyon: IARC Press, 2002; 86-90.

- 28. Fletcher CD, Bridge JA, Lee JC. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumour. In: Fletcher CD, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn CW, Mertens F, eds. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press, 2013; 80-2.

- 29. Salas S, Resseguier N, Blay JY, et al. Prediction of local and metastatic recurrence in solitary fibrous tumor: construction of a risk calculator in a multicenter cohort from the French Sarcoma Group (FSG) database. Ann Oncol 2017; 28: 1979-87. ArticlePubMed

- 30. Gholami S, Cassidy MR, Kirane A, et al. Size and location are the most important risk factors for malignant behavior in resected solitary fibrous tumors. Ann Surg Oncol 2017; 24: 3865-71. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 31. Demicco EG, Park MS, Araujo DM, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor: a clinicopathological study of 110 cases and proposed risk assessment model. Mod Pathol 2012; 25: 1298-306. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 32. Pasquali S, Gronchi A, Strauss D, et al. Resectable extra-pleural and extra-meningeal solitary fibrous tumours: a multi-centre prognostic study. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016; 42: 1064-70. ArticlePubMed

- 33. Makino H, Miyashita M, Nomura T, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the cervical esophagus. Dig Dis Sci 2007; 52: 2195-200. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 34. Bratton L, Salloum R, Cao W, Huber AR. Solitary fibrous tumor of the sigmoid colon masquerading as an adnexal neoplasm. Case Rep Pathol 2016; 2016: 4182026.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 35. Nielsen GP, Dickersin GR, Provenzal JM, Rosenberg AE. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma: a histologic, ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of a unique variant of hemangiopericytoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1995; 19: 748-56. PubMed

- 36. Yang EJ, Howitt BE, Fletcher CD, Nucci MR. Solitary fibrous tumour of the female genital tract: a clinicopathological analysis of 25 cases. Histopathology 2018; 72: 749-59. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 37. Rao N, Colby TV, Falconieri G, Cohen H, Moran CA, Suster S. Intrapulmonary solitary fibrous tumors: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 24 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2013; 37: 155-66. PubMed

- 38. Mena H, Ribas JL, Pezeshkpour GH, Cowan DN, Parisi JE. Hemangiopericytoma of the central nervous system: a review of 94 cases. Hum Pathol 1991; 22: 84-91. ArticlePubMed

- 39. Macagno N, Vogels R, Appay R, et al. Grading of meningeal solitary fibrous tumors/hemangiopericytomas: analysis of the prognostic value of the Marseille grading system in a cohort of 132 patients. Brain Pathol 2019; 29: 18-27. PubMed

- 40. Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Gittleman H, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2012-2016. Neuro Oncol 2019; 21: v1-100. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 41. Kouba E, Simper NB, Chen S, et al. Solitary fibrous tumour of the genitourinary tract: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases and their association with the NAB2-STAT6 fusion gene. J Clin Pathol 2017; 70: 508-14. ArticlePubMed

- 42. Sun S, Tang M, Dong H, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor involving urinary bladder: a case report and literature review. Transl Androl Urol 2020; 9: 766-75. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 43. Thompson LD, Wei C, Rooper LM, Lau SK. Thyroid gland solitary fibrous tumor: report of 3 cases and a comprehensive review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol 2019; 13: 597-605. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 44. Suh YJ, Park JH, Jeon JH, Bilegsaikhan SE. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumor of the thyroid gland: a case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8: 782-9. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 45. Demicco EG, Griffin AM, Gladdy RA, et al. Comparison of published risk models for prediction of outcome in patients with extrameningeal solitary fibrous tumour. Histopathology 2019; 75: 723-37. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 46. Thompson LD, Liou SS, Feldman KA. Orbit solitary fibrous tumor: a proposed risk prediction model based on a case series and comprehensive literature review. Head Neck Pathol 2021; 15: 138-52. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 47. Alkatan HM, Alsalamah AK, Almizel A, et al. Orbital solitary fibrous tumors: a multi-centered histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis with radiological description. Ann Saudi Med 2020; 40: 227-33. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 48. Krishnakumar S, Subramanian N, Mohan ER, Mahesh L, Biswas J, Rao NA. Solitary fibrous tumor of the orbit: a clinicopathologic study of six cases with review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol 2003; 48: 544-54. ArticlePubMed

- 49. Kim HJ, Kim HJ, Kim YD, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the orbit: CT and MR imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29: 857-62. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 50. Ng DW, Tan GH, Soon JJ, et al. The approach to solitary fibrous tumors: are clinicopathological features and nomograms accurate in the prediction of prognosis? Int J Surg Pathol 2018; 26: 600-8. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 51. Kayani B, Sharma A, Sewell MD, et al. A review of the surgical management of extrathoracic solitary fibrous tumors. Am J Clin Oncol 2018; 41: 687-94. ArticlePubMed

- 52. Thompson LD, Karamurzin Y, Wu ML, Kim JH. Solitary fibrous tumor of the larynx. Head Neck Pathol 2008; 2: 67-74. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 53. Thompson LD, Lau SK. Sinonasal tract solitary fibrous tumor: a clinicopathologic study of six cases with a comprehensive review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol 2018; 12: 471-80. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 54. Furusato E, Valenzuela IA, Fanburg-Smith JC, et al. Orbital solitary fibrous tumor: encompassing terminology for hemangiopericytoma, giant cell angiofibroma, and fibrous histiocytoma of the orbit: reappraisal of 41 cases. Hum Pathol 2011; 42: 120-8. ArticlePubMed

- 55. Bahrami A, Lee S, Schaefer IM, et al. TERT promoter mutations and prognosis in solitary fibrous tumor. Mod Pathol 2016; 29: 1511-22. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 56. Goellner JR, Laws ER, Soule EH, Okazaki H. Hemangiopericytoma of the meninges. Mayo Clinic experience. Am J Clin Pathol 1978; 70: 375-80. ArticlePubMed

- 57. Fukasawa Y, Takada A, Tateno M, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura causing recurrent hypoglycemia by secretion of insulin-like growth factor II. Pathol Int 1998; 48: 47-52. ArticlePubMed

- 58. De Los Santos-Aguilar RG, Chavez-Villa M, Contreras AG, et al. Successful multimodal treatment of an IGF2-producing solitary fibrous tumor with acromegaloid changes and hypoglycemia. J Endocr Soc 2019; 3: 537-43. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 59. Chen S, Zheng Y, Chen L, Yi Q. A broad ligament solitary fibrous tumor with Doege-Potter syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97: e12564. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 60. Denewar FA, Takeuchi M, Khedr D, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors from A to Z: a pictorial review with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Insights Imaging 2025; 16: 112.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 61. Xiao Y, Chen J, Yang W, Yan H, Chen R, Li Y. Solitary fibrous tumors: radiologic features with clinical and histopathologic correlation. Front Oncol 2025; 15: 1510059.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 62. Yi X, Wang J, Zhang Y, et al. Renal solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma: computed tomography findings and clinicopathologic features. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2019; 44: 642-51. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 63. Keraliya AR, Tirumani SH, Shinagare AB, Zaheer A, Ramaiya NH. Solitary fibrous tumors: 2016 imaging update. Radiol Clin North Am 2016; 54: 565-79. PubMed

- 64. Bhat A, Layfield LJ, Tewari SO, Gaballah AH, Davis R, Wu Z. Solitary fibrous tumor of the ischioanal fossa: a multidisciplinary approach to management with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiol Case Rep 2018; 13: 468-74. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 65. Fernandez A, Conrad M, Gill RM, Choi WT, Kumar V, Behr S. Solitary fibrous tumor in the abdomen and pelvis: a case series with radiological findings and treatment recommendations. Clin Imaging 2018; 48: 48-54. ArticlePubMed

- 66. Lococo F, Cafarotti S, Treglia G. Is 18F-FDG-PET/CT really able to differentiate between malignant and benign solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura? Clin Imaging 2013; 37: 976.ArticlePubMed

- 67. Lococo F, Rapicetta C, Filice A, et al. The role of 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT in the detection of relapsed malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol (Engl Ed) 2018; 37: 257-8. ArticlePubMed

- 68. Wang X, Qian J, Bi Y, Ping B, Zhang R. Malignant transformation of orbital solitary fibrous tumor. Int Ophthalmol 2013; 33: 299-303. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 69. Chen T, Jiang B, Zheng Y, et al. Differentiating intracranial solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma from meningioma using diffusion-weighted imaging and susceptibility-weighted imaging. Neuroradiology 2020; 62: 175-84. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 70. Stomeo F, Padovani D, Bozzo C, Pastore A. Laryngeal solitary fibrous tumour. Auris Nasus Larynx 2007; 34: 405-8. ArticlePubMed

- 71. Yang BT, Song ZL, Wang YZ, Dong JY, Wang ZC. Solitary fibrous tumor of the sinonasal cavity: CT and MR imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34: 1248-51. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 72. Yang BT, Wang YZ, Dong JY, Wang XY, Wang ZC. MRI study of solitary fibrous tumor in the orbit. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 199: W506-11. ArticlePubMed

- 73. Chmielecki J, Crago AM, Rosenberg M, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies a recurrent NAB2-STAT6 fusion in solitary fibrous tumors. Nat Genet 2013; 45: 131-2. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 74. Mohajeri A, Tayebwa J, Collin A, et al. Comprehensive genetic analysis identifies a pathognomonic NAB2/STAT6 fusion gene, nonrandom secondary genomic imbalances, and a characteristic gene expression profile in solitary fibrous tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2013; 52: 873-86. ArticlePubMed

- 75. Fritchie KJ, Jin L, Rubin BP, et al. NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion in meningeal hemangiopericytoma and solitary fibrous tumor. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2016; 75: 263-71. ArticlePubMed

- 76. Fritchie K, Jensch K, Moskalev EA, et al. The impact of histopathology and NAB2-STAT6 fusion subtype in classification and grading of meningeal solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma. Acta Neuropathol 2019; 137: 307-19. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 77. Demicco EG, Wani K, Ingram D, et al. TERT promoter mutations in solitary fibrous tumour. Histopathology 2018; 73: 843-51. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 78. Kurisaki-Arakawa A, Akaike K, Hara K, et al. A case of dedifferentiated solitary fibrous tumor in the pelvis with TP53 mutation. Virchows Arch 2014; 465: 615-21. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 79. Park HK, Yu DB, Sung M, et al. Molecular changes in solitary fibrous tumor progression. J Mol Med (Berl) 2019; 97: 1413-25. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 80. Liang Y, Heller RS, Wu JK, et al. High p16 expression is associated with malignancy and shorter disease-free survival time in solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 2019; 80: 232-8. ArticlePubMed

- 81. Adachi S, Kondo A, Ogino I, et al. The significance of cytoplasmic STAT6 positivity and high p53/p16 expression as a novel predictor of histological/clinical malignancy in NAB2::STAT6 fusion-positive orbital solitary fibrous tumors. Pathol Int 2025; 75: 513-22. Article

- 82. Koelsche C, Schweizer L, Renner M, et al. Nuclear relocation of STAT6 reliably predicts NAB2-STAT6 fusion for the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumour. Histopathology 2014; 65: 613-22. PubMed

- 83. Fukunaga M, Naganuma H, Nikaido T, Harada T, Ushigome S. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumor: a report of seven cases. Mod Pathol 1997; 10: 443-50. PubMed

- 84. Hasegawa T, Hirose T, Seki K, Yang P, Sano T. Solitary fibrous tumor of the soft tissue: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Am J Clin Pathol 1996; 106: 325-31. ArticlePubMed

- 85. Bakhshwin A, Berry RS, Cox RM, et al. Malignant solitary fibrous tumour of the prostate: four cases emphasising significant histological and immunophenotypical overlap with sarcomatoid carcinoma. Pathology 2020; 52: 643-8. ArticlePubMed

- 86. Westra WH, Grenko RT, Epstein J. Solitary fibrous tumor of the lower urogenital tract: a report of five cases involving the seminal vesicles, urinary bladder, and prostate. Hum Pathol 2000; 31: 63-8. ArticlePubMed

- 87. Smith SC, Gooding WE, Elkins M, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the head and neck: a multi-institutional clinicopathologic study. Am J Surg Pathol 2017; 41: 1642-56. PubMedPMC

- 88. Tariq MU, Din NU, Abdul-Ghafar J, Park YK. The many faces of solitary fibrous tumor: diversity of histological features, differential diagnosis and role of molecular studies and surrogate markers in avoiding misdiagnosis and predicting the behavior. Diagn Pathol 2021; 16: 32.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 89. Bauer JL, Miklos AZ, Thompson LD. Parotid gland solitary fibrous tumor: a case report and clinicopathologic review of 22 cases from the literature. Head Neck Pathol 2012; 6: 21-31. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 90. Carneiro SS, Scheithauer BW, Nascimento AG, Hirose T, Davis DH. Solitary fibrous tumor of the meninges: a lesion distinct from fibrous meningioma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Am J Clin Pathol 1996; 106: 217-24. ArticlePubMed

- 91. Cassarino DS, Auerbach A, Rushing EJ. Widely invasive solitary fibrous tumor of the sphenoid sinus, cavernous sinus, and pituitary fossa. Ann Diagn Pathol 2003; 7: 169-73. ArticlePubMed

- 92. Metellus P, Bouvier C, Guyotat J, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the central nervous system: clinicopathological and therapeutic considerations of 18 cases. Neurosurgery 2007; 60: 715-22. PubMed

- 93. Folpe AL, Devaney K, Weiss SW. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma: a rare variant of hemangiopericytoma that may be confused with liposarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1999; 23: 1201-7. PubMed

- 94. Guillou L, Gebhard S, Coindre JM. Lipomatous hemangiopericytoma: a fat-containing variant of solitary fibrous tumor? Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural analysis of a series in favor of a unifying concept. Hum Pathol 2000; 31: 1108-15. ArticlePubMed

- 95. Chen Y, Wang F, Han A. Fat-forming solitary fibrous tumor of the kidney: a case report and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015; 8: 8632-5. PubMedPMC

- 96. Lee JC, Fletcher CD. Malignant fat-forming solitary fibrous tumor (so-called "lipomatous hemangiopericytoma"): clinicopathologic analysis of 14 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2011; 35: 1177-85. PubMed

- 97. Dei Tos AP, Seregard S, Calonje E, Chan JK, Fletcher CD. Giant cell angiofibroma: a distinctive orbital tumor in adults. Am J Surg Pathol 1995; 19: 1286-93. PubMed

- 98. Guillou L, Gebhard S, Coindre JM. Orbital and extraorbital giant cell angiofibroma: a giant cell-rich variant of solitary fibrous tumor? Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of a series in favor of a unifying concept. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24: 971-9. PubMed

- 99. de Saint Aubain Somerhausen N, Rubin BP, Fletcher CD. Myxoid solitary fibrous tumor: a study of seven cases with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Mod Pathol 1999; 12: 463-71. PubMed

- 100. Fukunaga M, Naganuma H, Ushigome S, Endo Y, Ishikawa E. Malignant solitary fibrous tumour of the peritoneum. Histopathology 1996; 28: 463-6. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 101. Vallat-Decouvelaere AV, Dry SM, Fletcher CD. Atypical and malignant solitary fibrous tumors in extrathoracic locations: evidence of their comparability to intra-thoracic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 1998; 22: 1501-11. PubMed

- 102. Gold JS, Antonescu CR, Hajdu C, et al. Clinicopathologic correlates of solitary fibrous tumors. Cancer 2002; 94: 1057-68. ArticlePubMed

- 103. Demicco EG, Wagner MJ, Maki RG, et al. Risk assessment in solitary fibrous tumors: validation and refinement of a risk stratification model. Mod Pathol 2017; 30: 1433-42. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 104. Magro G, Emmanuele C, Lopes M, Vallone G, Greco P. Solitary fibrous tumour of the kidney with sarcomatous overgrowth: case report and review of the literature. APMIS 2008; 116: 1020-5. ArticlePubMed

- 105. Masuda Y, Kurisaki-Arakawa A, Hara K, et al. A case of dedifferentiated solitary fibrous tumor of the thoracic cavity. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014; 7: 386-93. PubMed

- 106. Subramaniam MM, Lim XY, Venkateswaran K, Shuen CS, Soong R, Petersson F. Dedifferentiated solitary fibrous tumour of the nasal cavity: the first case reported with molecular characterization of a TP53 mutation. Histopathology 2011; 59: 1269-74. ArticlePubMed

- 107. Akaike K, Kurisaki-Arakawa A, Hara K, et al. Distinct clinicopathological features of NAB2-STAT6 fusion gene variants in solitary fibrous tumor with emphasis on the acquisition of highly malignant potential. Hum Pathol 2015; 46: 347-56. ArticlePubMed

- 108. Thway K, Hayes A, Ieremia E, Fisher C. Heterologous osteosarcomatous and rhabdomyosarcomatous elements in dedifferentiated solitary fibrous tumor: further support for the concept of dedifferentiation in solitary fibrous tumor. Ann Diagn Pathol 2013; 17: 457-63. ArticlePubMed

- 109. Mosquera JM, Fletcher CD. Expanding the spectrum of malignant progression in solitary fibrous tumors: a study of 8 cases with a discrete anaplastic component: is this dedifferentiated SFT? Am J Surg Pathol 2009; 33: 1314-21. PubMed

- 110. Collini P, Negri T, Barisella M, et al. High-grade sarcomatous overgrowth in solitary fibrous tumors: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2012; 36: 1202-15. PubMed

- 111. Tardio JC, Machado I, Alemany I, Lopez-Soto MV, Nieto MG, Llombart-Bosch A. Solitary fibrous tumor of the vulva: report of 2 cases, including a de novo dedifferentiated solitary fibrous tumor diagnosed after molecular demonstration of NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2018; 37: 547-53. ArticlePubMed

- 112. Olson NJ, Linos K. Dedifferentiated solitary fibrous tumor: a concise review. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2018; 142: 761-6. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 113. Demicco EG, Harms PW, Patel RM, et al. Extensive survey of STAT6 expression in a large series of mesenchymal tumors. Am J Clin Pathol 2015; 143: 672-82. ArticlePubMed