Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Pathol Transl Med > Forthcoming articles > Article

-

Case Study

Drug-induced phospholipidosis of the kidney suspected to be caused by atomoxetine -

Sung-Eun Choi1

, Kee Hyuck Kim2

, Kee Hyuck Kim2 , Minsun Jung3

, Minsun Jung3 , Jeong Hae Kie1

, Jeong Hae Kie1

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2025.12.10

Published online: January 7, 2026

1Department of Pathology, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea

2Department of Pediatrics, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea

3Department of Pathology, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- Corresponding author: Jeong Hae Kie, MD, PhD Department of Pathology, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital, 100 Ilsan-ro, Goyang 10444, Korea Tel: +82-31-780-0892, Fax: , E-mail: jhkie88@nhimc.or.kr

© The Korean Society of Pathologists/The Korean Society for Cytopathology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 103 Views

- 5 Download

Abstract

- Fabry disease and drug-induced phospholipidosis (DIP) both exhibit zebra bodies on electron microscopy, complicating differential diagnosis. A 17-year-old male with microscopic hematuria and proteinuria had received atomoxetine (40 mg) for 11 months to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Light microscopy showed one glomerulus with perihilar sclerosis and periglomerular fibrosis. Kidney biopsy revealed zebra bodies in podocytes, initially suggesting Fabry disease. However, α-galactosidase A enzyme activity was normal on tandem mass spectrometry. Next-generation sequencing of GLA identified only three benign variants. This represents the first reported case of atomoxetine-induced DIP. When zebra bodies are observed, clinicians should consider DIP caused by cationic amphiphilic drugs alongside Fabry disease. Atomoxetine meets the structural criteria for inducing DIP, and awareness of this potential complication is essential.

- Fabry disease is a rare metabolic disorder characterized by systemic glycosphingolipid accumulation. As it is X-linked, males generally have more severe symptoms and faster progression than females [1]. However, there have been many reports of atypical variants in males with late onset and involvement of a single organ [2]. It is thought that this milder disease phenotype is due to a certain level of residual enzyme activity associated with missense mutations [3]. Pathological findings on kidney biopsy include enlarged and vacuolated podocytes on light microscopy, along with lamellated lipid inclusions (known as “zebra bodies”) in the vacuoles, which can be seen under an electron microscope [4]. Therefore, if zebra bodies are observed on kidney biopsy of a pediatric patient with proteinuria, Fabry disease should generally be considered the primary diagnosis.

- However, drug-induced phospholipidosis (DIP) exhibits almost identical pathological findings to Fabry disease [5]. It is diagnosed by first ruling out Fabry disease and then identifying any suspected drugs, which may include hydroxychloroquine [5-8] or amiodarone [9,10]. Herein, we describe a case of DIP in association with atomoxetine (Strattera), a treatment for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of atomoxetine as a possible causative agent for DIP.

INTRODUCTION

- A 17-year-old male patient visited our outpatient clinic after a school urine test showed microscopic hematuria and proteinuria. There were no specific symptoms. Prior to this visit, he had taken 40 mg of atomoxetine daily for 12 months as a treatment for ADHD. Proteinuria persisted for 28 months in urine tests conducted every 6 months; urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio gradually increased from 412 µg/mgCr to 474.6 µg/mgCr over 17 months, while the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR) increased from 629.9 mg/g to 666.7 mg/g over the same period. A kidney biopsy was performed to determine the cause of proteinuria.

- At the time of renal biopsy, the patient was normotensive (120/70 mmHg of blood pressure) with a normal heart rate (61 beats per minute) and a body mass index of 26.7. There was no edema. Physical examination was unremarkable otherwise. Urine analysis showed proteinuria (3+) and microscopic hematuria (1+, red blood cell [RBC] 6–10/high-power field) with dysmorphic RBCs (13%). UPCR was 1,392.5 mg/g. Serum creatinine was 0.78 mg/dL. Serum albumin was 4.4 g/dL. Cholesterol level was 195 mg/dL. C-reactive protein was not elevated at less than 0.2 mg/dL. C3 level was normal at 113 mg/dL. Anti-nuclear antibody and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were not detected.

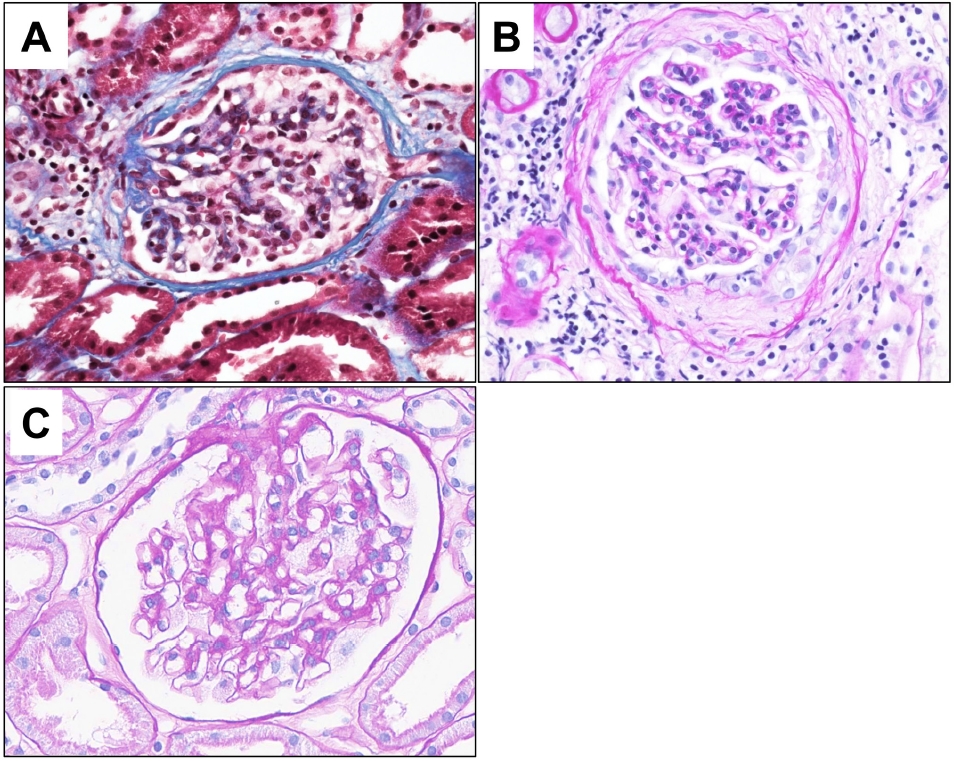

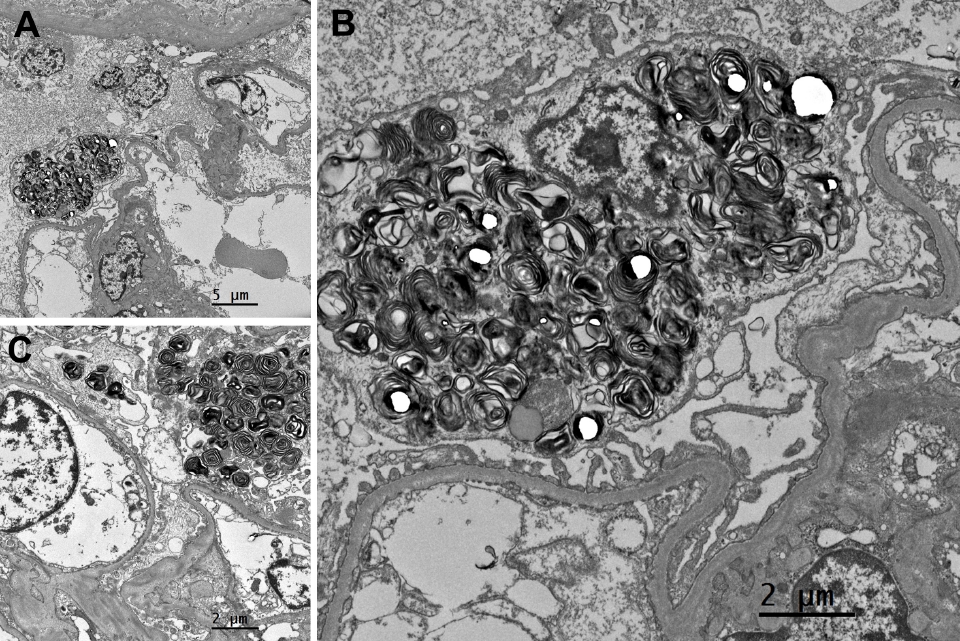

- On light microscopy, a total of 20 glomeruli were present. A glomerulus with perihilar sclerosis was noted; it also had periglomerular fibrosis with Bowman’s capsule wrinkling (Fig. 1). The other glomeruli were normocellular without mesangial expansion or size enlargement. The capillary loops were patent without collapse. The glomerular basement membrane was not thickened or duplicated. Tubules showed mild atrophy with focal proteinaceous casts. Mild interstitial fibrosis was present with mild inflammatory infiltrates. Vessels were unremarkable. On immunofluorescent microscopy, six glomeruli were present. Minimal to mild deposits of C3 were present in the mesangium of the glomeruli. No deposits of IgG, IgA, IgM, C4, C1q, fibrinogen, kappa, or lambda were identified. On electron microscopy (EM), alternating lamellar structures of electron-dense and electron-lucent area, known as myeloid or zebra bodies, were identified in the cytoplasm of podocytes (Fig. 2). The foot processes were diffusely effaced, covering around 100% of the area. Based on histopathology findings, Fabry disease with secondary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis was suspected.

- To confirm the diagnosis, the activity level of α-galactosidase A enzyme was measured using tandem mass spectrometry. The enzyme activity was within normal limits. Next-generation sequencing was performed on GLA, encompassing the coding region and the ±25 base pairs of the flanking region. The result was negative for all pathogenic, likely pathogenic, and variants of undetermined significance; only three benign variants were identified. Thorough family history taking was done, but none of the family members had typical symptoms or signs of Fabry disease, including paresthesia, renal dysfunction, cardiac arrythmia, or myocardial infarction. The patient also had no industrial exposure to silicon, which ruled out the possibility of silicon nephropathy. Taken together, the final diagnosis was DIP.

- He was started on losartan, an angiotensin II receptor blocker, at a dose of 50 mg daily. He has been attending the outpatient clinic regularly every 6 months, with proteinuria and renal function remaining stable. Hematuria remained at 1+, and UPCR increased slightly to 1,948.3 mg/g at the last visit.

CASE REPORT

- Fabry disease is an X-linked inherited disorder characterized by multiple systemic manifestations due to inherent shortages of an enzyme, α-galactosidase A, or its inactivity. α-galactosidase A is a hydrolase that resides in lysosomes and its deficiency leads to the progressive accumulation of glycosphingolipids such as globotriaosylceramide (GL-3), which impairs the function of tissues and organs. The symptoms of Fabry disease include paresthesias in the extremities, angiokeratomas, corneal opacity, anhidrosis, and heart and cerebrovascular dysfunction. When the kidney is affected, proteinuria and hematuria may occur, and in most cases, it progresses to renal failure when patients reach their 30s to 40s [11]. Typical light microscopic findings include foamy and vacuolated podocytes. On EM, enlarged lysosomes are filled with osmiophilic and lamellated membrane structures showing an onion skin-like appearance or parallel dense layers, so called myeloid or “zebra” bodies. Inclusions related to accumulated GL-3 are typically present in podocytes. They are also present in the mesangium, parietal epithelium, tubular epithelium, and vascular myocytes. In this case, although the patient had zebra bodies on EM, there were no relevant symptoms or family history.

- Although rare, atypical Fabry disease must also be considered in the differential diagnosis. The distinguishing features of this condition include a later onset, milder symptoms, and higher α-galactosidase A activity (ranging from 1% to 35% compared to less than 1% in the classic form). While the condition is primarily observed in females due to its X-linked nature, it has been documented in 1.2% of males with end-stage kidney disease on hemodialysis [2]. It is possible for patients with atypical Fabry disease to exhibit near-normal α-galactosidase A activity, which is consistent with the observations made in this case. In such case, measuring GL-3 levels would be informative. We were unable to measure GL-3 levels due to practical constraints, which is a limitation. Despite the fact that routine sequence analysis is reported to encompass up to 95% of pathogenic variants [2], approximately 5% are likely to be identified exclusively through gene-targeted deletion/duplication analysis [2]. Although there are limitations to our analysis, including the absence of GL-3 level measurement and deletion/duplication assays, which prevent the complete exclusion of atypical Fabry disease, the absence of abnormalities in other organs, especially the heart, and the patient’s relatively young age of 17 years at the time of biopsy led to a diagnosis of DIP.

- Another differential diagnosis that causes zebra bodies is DIP. Due to their physicochemical structure, cationic amphiphilic drugs (CADs) can easily pass through cell membranes, as they have both hydrophobic and hydrophilic domains. The acidic nature of the lysosome appears to provide a favorable environment for basic CADs to accumulate and become entrapped through protonation [12]. CADs inhibit lysosomal phospholipase activity by forming indigestible complexes with phospholipids [13], or by directly inhibiting phospholipase [14]. This leads to phospholipids accumulating in lysosomes [12]. Patients with DIP related to CADs may exhibit less extensive zebra bodies than those with Fabry disease [6] or curvilinear bodies (i.e., twisted microtubular structure). However, neither of these is a definitive distinguishing factor.

- Drugs such as hydroxychloroquine [7,8], amiodarone [9], and ranolazine [15] have been reported to cause phospholipidosis in the kidney. Atomoxetine is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that has been used to treat ADHD since 2002. Although atomoxetine has not been reported to cause DIP, its structure meets the criteria of CADs. It has a primary amine group corresponding to the hydrophilic domain, as well as two aromatic rings—a phenyl ring and an o-tolyl ether—corresponding to the hydrophobic domain [16]. The circumstances in which CADs can cause phospholipidosis are not well understood. The cumulative dose of the drug may be associated with this condition [17], but experiments in animals and in vivo to verify this have not yet been conducted. Similarly, the time to recover renal function following drug withdrawal varies, and full recovery does not always occur [8]. In this case, almost all the foot processes of the podocytes were effaced, and perihilar sclerosis progressed. Therefore, even after discontinuing the medication for 10 years, it is possible that proteinuria will persist.

- Various types of drugs, such as antidepressants, antibiotics, antiarrhythmics, and antimalarials, belong to the CAD category, but their association with phospholipidosis and the mechanisms that cause cellular and clinical toxicity are relatively poorly understood. Although a predictive biomarker for phospholipidosis (i.e., urine di-22:6-BMP [18]) has been discovered, it is expected to be some time before it is introduced into drug monitoring in practice.

- Zebra bodies were once considered a definitive finding of Fabry disease [19], but are now considered not uncommon in cases of DIP or silicon nephropathy [20]. Since many drugs belong to the CAD class, if zebra bodies are found in EM, DIP should be considered alongside Fabry disease.

DISCUSSION

Ethics Statement

All procedures performed in the current study were exempted from review by the Institutional Review Board (NHIMC IRB 2025-08-012, 2025-08-21) in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments, and written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Availability of Data and Material

1. The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

2. All data generated or analyzed during the study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

3. The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are not publicly available due [REASON(S) WHY DATA ARE NOT PUBLIC] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

4. The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available in the [NAME] repository, [PERSISTENT WEB LINK TO DATASETS]

5. Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: JHK. Investigation: JHK, KHK, SEC. Visualization: JHK, MJ, SEC. Writing—original draft: SEC. Writing—review & editing: all authors. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding to declare.

- 1. Mehta A, Widmer U. Natural history of Fabry disease. In: Mehta A, Beck M, Sunder-Plassmann G, eds. Fabry disease: perspectives from 5 years of FOS. Oxford: Oxford PharmaGenesis, 2006.

- 2. Nakao S, Kodama C, Takenaka T, et al. Fabry disease: detection of undiagnosed hemodialysis patients and identification of a "renal variant" phenotype. Kidney Int 2003; 64: 801-7. ArticlePubMed

- 3. Ries M, Gal A. Genotype-phenotype correlation in Fabry disease. In: Mehta A, Beck M, Sunder-Plassmann G, eds. Fabry disease: perspectives from 5 years of FOS. Oxford: Oxford PharmaGenesis, 2006.

- 4. Woywodt A, Hellweg S, Schwarz A, Schaefer RM, Mengel M. A wild zebra chase. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007; 22: 3074-7. ArticlePubMed

- 5. Bracamonte ER, Kowalewska J, Starr J, Gitomer J, Alpers CE. Iatrogenic phospholipidosis mimicking Fabry disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48: 844-50. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Costa RM, Martul EV, Reboredo JM, Cigarran S. Curvilinear bodies in hydroxychloroquine-induced renal phospholipidosis resembling Fabry disease. Clin Kidney J 2013; 6: 533-6. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Khubchandani SR, Bichle LS. Hydroxychloroquine-induced phospholipidosis in a case of SLE: the wolf in zebra clothing. Ultrastruct Pathol 2013; 37: 146-50. ArticlePubMed

- 8. de Menezes Neves PD, Machado JR, Custodio FB, et al. Ultrastructural deposits appearing as "zebra bodies" in renal biopsy: Fabry disease? Comparative case reports. BMC Nephrol 2017; 18: 157.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Pintavorn P, Cook WJ. Progressive renal insufficiency associated with amiodarone-induced phospholipidosis. Kidney Int 2008; 74: 1354-7. ArticlePubMed

- 10. Duineveld MD, Kers J, Vleming LJ. Case report of progressive renal dysfunction as a consequence of amiodarone-induced phospholipidosis. Eur Heart J Case Rep 2023; 7: ytad457.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 11. Najafian B, Mauer M, Hopkin RJ, Svarstad E. Renal complications of Fabry disease in children. Pediatr Nephrol 2013; 28: 679-87. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 12. Lullmann H, Lullmann-Rauch R, Wassermann O. Lipidosis induced by amphiphilic cationic drugs. Biochem Pharmacol 1978; 27: 1103-8. ArticlePubMed

- 13. Lullmann-Rauch R. Drug-induced lysosomal storage disorders. Front Biol 1979; 48: 49-130. PubMed

- 14. Kubo M, Hostetler KY. Mechanism of cationic amphiphilic drug inhibition of purified lysosomal phospholipase A1. Biochemistry 1985; 24: 6515-20. ArticlePubMed

- 15. Scheurle C, Dammrich M, Becker JU, Baumgartel MW. Renal phospholipidosis possibly induced by ranolazine. Clin Kidney J 2014; 7: 62-4. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Reasor MJ, Hastings KL, Ulrich RG. Drug-induced phospholipidosis: issues and future directions. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2006; 5: 567-83. ArticlePubMed

- 17. Vater M, Mockl L, Gormanns V, et al. New insights into the intracellular distribution pattern of cationic amphiphilic drugs. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 44277.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 18. Tengstrand E, Zhang H, Liu N, Dunn K, Hsieh F. A multiplexed UPLC-MS/MS assay for the simultaneous measurement of urinary safety biomarkers of drug-induced kidney injury and phospholipidosis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2019; 366: 54-63. ArticlePubMed

- 19. Alroy J, Sabnis S, Kopp JB. Renal pathology in Fabry disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 13 Suppl 2: S134-8. ArticlePubMed

- 20. Banks DE, Milutinovic J, Desnick RJ, Grabowski GA, Lapp NL, Boehlecke BA. Silicon nephropathy mimicking Fabry's disease. Am J Nephrol 1983; 3: 279-84. ArticlePubMed

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link-

Cite this Article

Cite this Article

- Cite this Article

-

- Close

- Download Citation

- Close

- Figure

E-submission

E-submission