Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Pathol Transl Med > Volume 59(2); 2025 > Article

-

Case Study

Uncommon granulomatous manifestation in Epstein-Barr virus–positive follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: a case report -

Henry Goh Di Shen1,*

, Yue Zhang1,*

, Yue Zhang1,* , Wei Qiang Leow1,2,3

, Wei Qiang Leow1,2,3

-

Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine 2025;59(2):133-138.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2024.09.27

Published online: October 31, 2024

1Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore

2Department of Anatomical Pathology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

3School of Biological Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

- Corresponding Author: Henry Goh Di Shen, Duke-NUS Medical School, 8 College Rd, 169857 Singapore Tel: +65-88772440, E-mail: henry.g@u.duke.nus.edu

- *Henry Goh Di Shen and Yue Zhang contributed equally to this work.

© The Korean Society of Pathologists/The Korean Society for Cytopathology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

- Hepatic Epstein-Barr virus–positive inflammatory follicular dendritic cell sarcoma (EBV+ IFDCS) represents a rare form of liver malignancy. The absence of distinct clinical and radiological characteristics, compounded by its rare occurrence, contributes to a challenging diagnosis. Here, we report a case of a 54-year-old Chinese female with a background of chronic hepatitis B virus treated with entecavir and complicated by advanced fibrosis presenting with a liver mass found on her annual surveillance ultrasound. Hepatectomy was performed under clinical suspicion of hepatocellular carcinoma. Immunomorphologic characteristics of the tumor were consistent with EBV+ IFDCS with distinct non-caseating granulomatous inflammation. Our case illustrates the importance of considering EBV+ IFDCS in the differential diagnosis of hepatic inflammatory lesions. Awareness of this entity and its characteristic features is essential for accurately diagnosing and managing this rare neoplasm.

- Epstein-Barr virus–positive inflammatory follicular dendritic cell sarcoma (EBV+ IFDCS), previously known as inflammatory pseudotumor-like follicular/fibroblastic dendritic cell sarcoma, is a rare, indolent malignancy arising from follicular dendritic cells (FDCs). The condition is characterized by spindle-shaped neoplastic cells dispersed in a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, primarily affects the liver and spleen of middle-aged adults, and shows a significant female predominance [1,2]. The pathological diagnosis of this neoplasm presents challenges due to its wide range of histological features and close resemblance to inflammatory lesions [3]. The complexity of diagnosis is further highlighted by recent reports of granuloma or eosinophilia-rich variants [4] and a lymphoma-like subtype [5]. Here, we present a rare case of EBV+ IFDCS with prominent epithelioid granulomas in a chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) carrier with METAVIR F2 fibrosis. The presence of granulomas in this context adds to the evidence for emerging histopathological variants of EBV+ IFDCS. Through detailed clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical analysis, this report aims to underscore the challenges of diagnosis amid the complex interplay of chronic liver disease, viral infections, and rare hepatic neoplasms.

INTRODUCTION

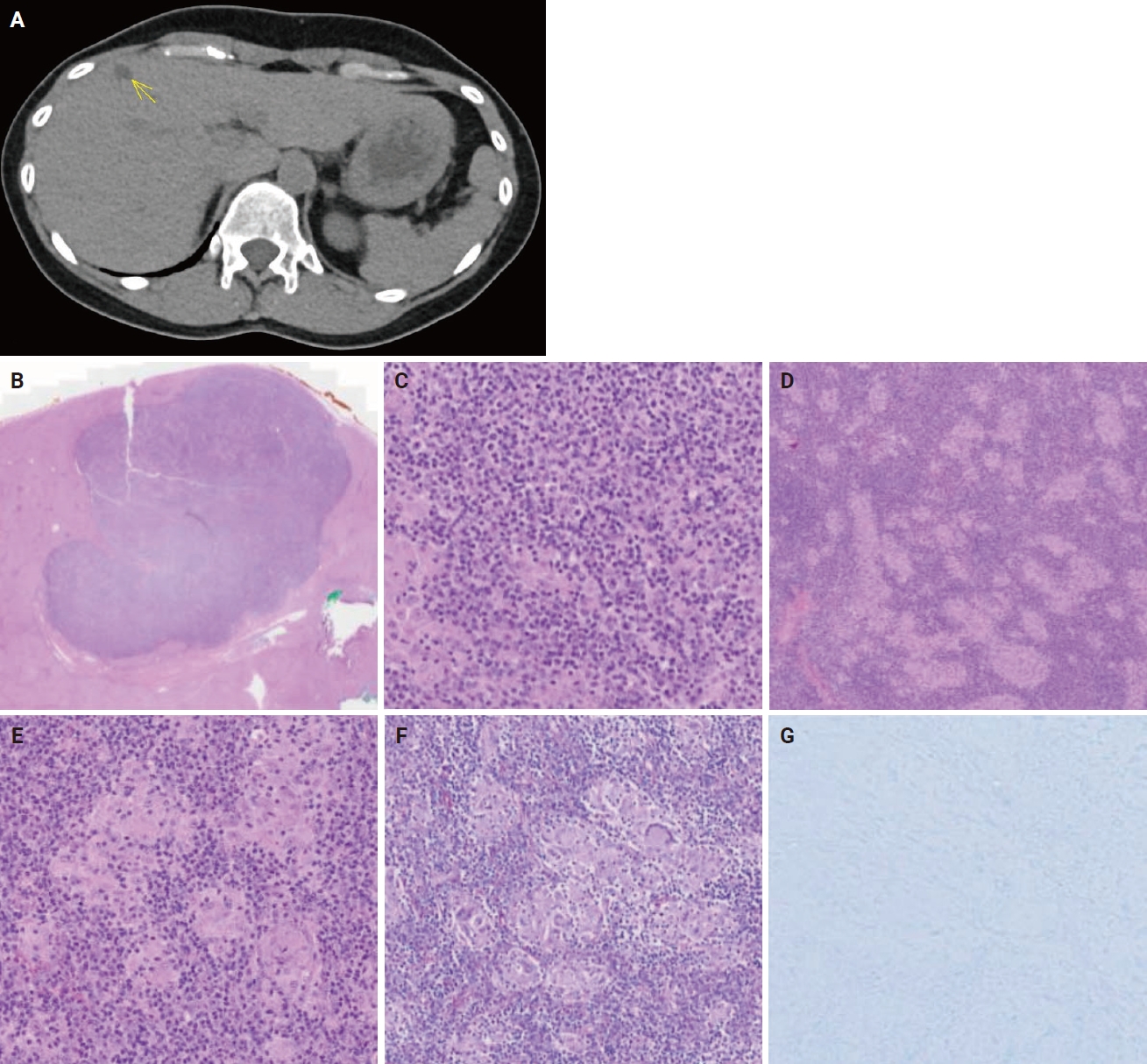

- A 54-year-old female patient has a history of hyperlipidemia, mitral valve prolapse, obsessive-compulsive behavior, epilepsy, and chronic hepatitis B treated with entecavir, complicated by advanced fibrosis with a liver stiffness of 11.4 kPa. She presented with an asymptomatic liver lesion, a cyst with septation and vascularity on annual surveillance ultrasound, suspicious for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Baseline alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, and α-fetoprotein levels remained within normal limits at 15 U/L (reference range, 6 to 66 U/L), 15 U/L (reference range, 12 to 42 U/L), and <2.7 μg/L (reference range, <7.1 μg/L), respectively. The patient then underwent a computed tomography scan of the liver, which revealed a 1.3-cm arterial enhancing lesion in hepatic segment IVb with associated washout and capsule appearance, suspicious for HCC (Fig. 1A). No other suspicious hepatic lesions were identified, and the portal and hepatic veins were patent. The patient underwent elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy and segment IVb wedge resection for suspected HCC and gallstones. The patient tolerated the procedure well, and the surgical specimen was submitted for histopathological analysis.

- The patient at 1 year of follow-up showed no palpable lymph nodes or abdominal masses. A positron emission tomography–computed tomography scan performed 2 weeks prior showed no evidence of hypermetabolic local recurrence at the surgical bed. Scattered nonspecific pulmonary nodules and clusters of centrilobular/tree-in-bud nodularities were noted, which may represent small airway infection or inflammation. No fluorodeoxyglucose-avid nodal metastases were detected. Liver function tests showed a slightly elevated alkaline phosphatase of 120 U/L (reference range, 39 to 99 U/L). HBV DNA load was detected at 11 IU/mL (1.06 log), for which she received tenofovir. The results of quantitative EBV polymerase chain reaction were undetectable, and alpha-fetoprotein level was within normal limits. The patient was planned for continued surveillance with a follow-up visit.

- Pathological examination

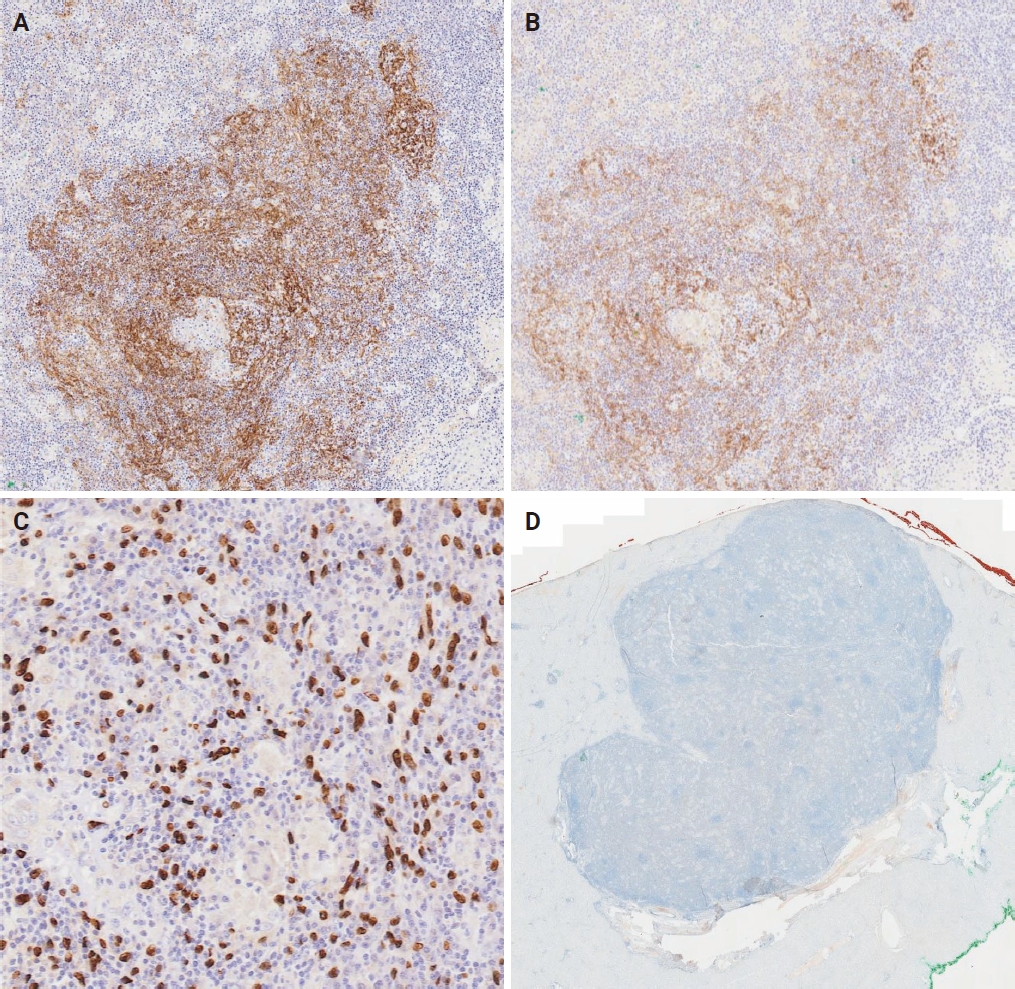

- Gross examination of the resected specimen revealed a firm, white, multi-nodular mass within the subcapsular region of the liver, measuring 1.8×1.8×1.1 cm. Low-magnification microscopic examination identified a distinct, expansile nodule characterized by sharply demarcated borders (Fig. 1B). At higher magnifications, neoplastic cells, ranging from oval to spindle-shaped, were dispersed within the inflammatory infiltrate, accompanied by reactive lymphoid follicles. These tumor cells displayed varying cytoplasmic volumes, ill-defined cell borders, irregular nuclear contours, and vesicular nuclei with distinct nucleoli, including some with binucleated and rare multinucleated forms (Fig. 1C). This background infiltration exhibited a pronounced lymphoplasmacytic inflammation interspersed with epithelioid histiocytes and micro-granulomas, along with the occasional presence of multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 1D, E). Notably, there was an absence of central caseation within the granulomas, and no foreign bodies were identified. In addition, fungal organisms were not detected with Grocott’s methenamine silver and periodic acid–Schiff special stains (Fig. 1F), and no acid-fast bacilli were noted with Ziehl-Neelsen and Fite-Faraco special stains (Fig. 1G). Victoria blue staining identified hepatitis B surface antigens and occasional fibrous expansions of portal tracts with fibrous septa, consistent with METAVIR F2 fibrosis.

- The granulomatous features observed in this case, characterized by epithelioid histiocytes, micro-granulomas, and multinucleated giant cells without central caseation, align with the rare granuloma-rich variant of EBV+ IFDCS. This variant remains underreported in the literature, particularly in the liver, where the differential diagnosis includes a wide range of infectious and inflammatory conditions [6]. Notably, the granulomas observed here lack central necrosis, distinguishing them from granulomas associated with infections such as tuberculosis or fungal diseases.

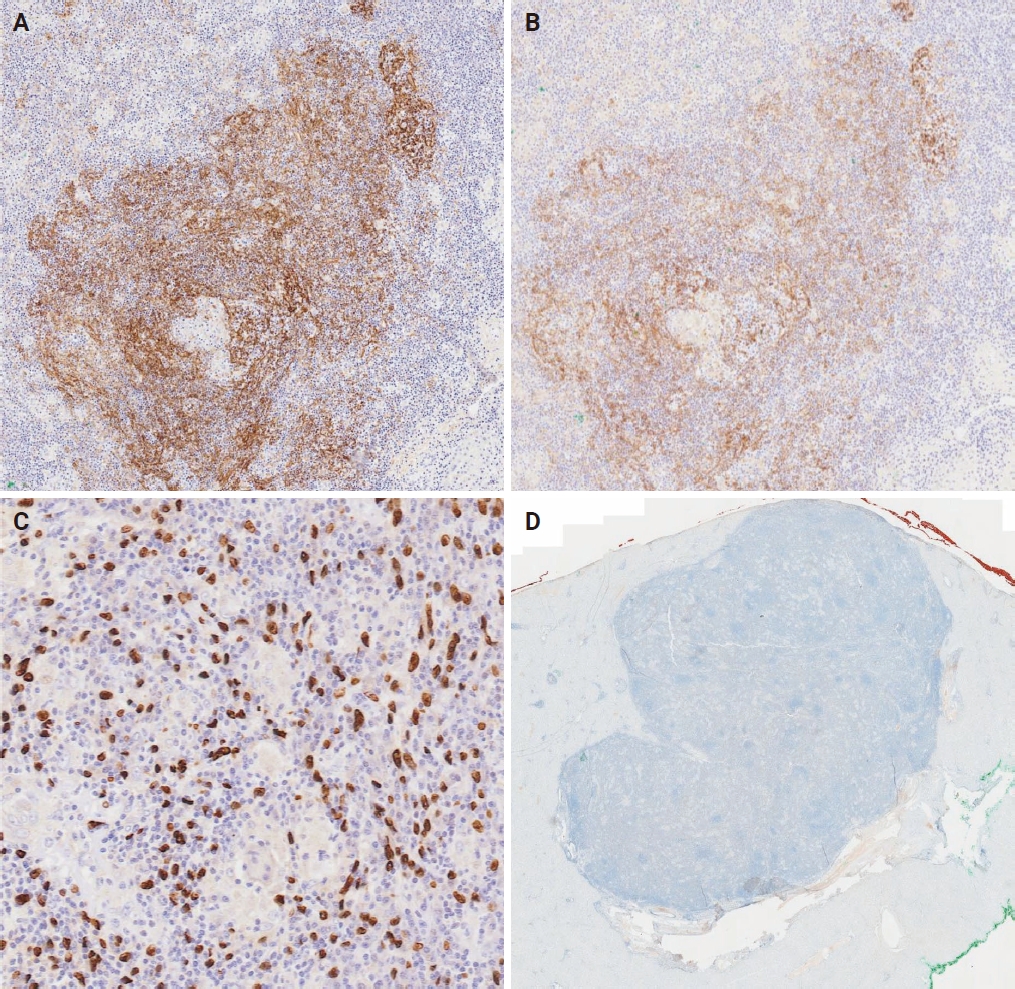

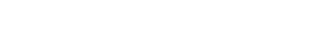

- Immunohistochemical analysis showed that a subset of neoplastic cells variably expressed FDC markers CD21 and CD35 (Fig. 2A, B). Disrupted follicular dendritic networks, within which neoplastic cells emerged, were also highlighted. In situ hybridization for EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER) was positive, marking both large pleomorphic nuclei and slender, occasionally tadpole-shaped nuclei of tumor cells (Fig. 2C). A mixed population of CD20-positive B-cells, CD3-positive T cells, and CD68-positive histiocytes was observed in the background, alongside interspersed plasma cells. The cell proliferation marker MIB1 indicated a low proliferative index of approximately 10%.

CASE REPORT

- EBV+ IFDCS is closely associated with EBV infection, often showing positivity for EBV via EBER in situ hybridization, suggesting that EBV is contributory to the development of this tumor. While the precise pathogenetic mechanism by which EBV drives the tumorigenesis of EBV+ IFDCS is not fully understood, it is theorized that latent Type 1 EBV infection of B lymphocytes leads to opportunistic infection of follicular dendritic cells due to their close functional associations in the context of immune function. EBER and latent membrane protein-1 from EBV then lead to cellular proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis through amplification of CD40 signaling [7]. Other contributory mechanisms include immune dysregulation due to latent EBV infection, supported by an observation of heavy IgG4+ plasma cell infiltration and activation in six cases of splenic EBV+ IFDCS [8].

- The diagnosis of EBV+ IFDCS relies on the combination of histopathological key features of spindle cells within a prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and a high index of suspicion. Immunohistochemistry includes variable positivity for FDC markers (CD21, CD23, CD35, CNA.42; with CD21 and CD35 having the highest specificity), and positive EBER in situ hybridization can help confirm the diagnosis. The diagnosis is further complicated by two identified morphological variants of the disease, which include the presence of epithelioid granulomas or pronounced tissue eosinophilia [4]. In addition, the lymphoma-like subtype and hemangioma-like subtype are also described in a recent publication [5]. These nuances highlight the intricate nature of this disease and the challenges in its diagnosis.

- The differentials for EBV+ IFDCS include inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT), which is histologically similar, containing loose spindle cells and mixed inflammatory infiltrates, but is associated with gene fusions such as anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and ROS1, with more than 50% of IMTs containing ALK fusions, of which the ALK immunostain was negative in this case (Fig. 2D) [9]. It is also important to rule out mimics of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor, including a benign inflammatory response to an adjacent abscess, IgG4-related sclerosing disease, and inflammatory variants of angiomyolipoma or hepatocellular adenomas. Granulomatous inflammation is an uncommon finding in EBV+ IFDCS and is particularly rare in hepatic presentations of this disease. The presence of granulomas in this case underscores the diagnostic challenge, as granulomas are often associated with a broad range of differential diagnoses, including infections (e.g., tuberculosis, fungal infections), autoimmune conditions (e.g., sarcoidosis), and other granulomatous diseases (e.g. Langerhans cell histiocytosis).

- Recent reports have begun to describe granuloma-rich variants of EBV+ IFDCS [4,6], yet the pathophysiological significance of granuloma formation in these cases remains unclear. The formation of granulomas in EBV+ IFDCS may be influenced by a combination of factors, including chronic viral infections such as EBV and HBV and the resultant immune dysregulation. It has been suggested that granulomas may represent a localized immune response to EBV-infected neoplastic cells or a secondary reaction to tumor necrosis or adjacent liver fibrosis [10]. EBV’s role in chronic inflammation and immune activation could promote the recruitment and activation of macrophages and T cells, contributing to granuloma formation [6]. Furthermore, chronic liver disease with fibrosis may alter the local immune microenvironment, potentially enhancing granulomatous inflammation. This case adds valuable insight into this rare histopathological variant, particularly in the setting of chronic liver disease and hepatitis B infection, where immune modulation may play a critical role in granuloma formation.

- The prognosis of EBV+ IFDCS is generally more favorable compared to classical follicular dendritic cell sarcoma (FDCS). While classical FDCS demonstrates a significant risk of local recurrence and distant metastasis, leading to a notable mortality rate, EBV+ IFDCS tends to exhibit less aggressive behavior, following an indolent course. A meta-analysis performed by Wu et al. [11] reported 1-year and 5-year progression-free survival of 91.5% and 56.1%, respectively, with a local and/or distant recurrence rate of 15.8% [11]. This calls into question whether the label of sarcoma in EBV+ IFDCS is better served than a label of tumor, considering that on the spectrum of EBV+ IFDCS, its behavior is more akin to an inflammatory pseudotumor rather than FDCS. Several factors, such as the size and location of the tumor, presence of atypia, necrosis, and metastasis, are known to influence the prognosis of FDCS. Of note, factors such as age, sex, tumor size, and specific pathological characteristics have not been significantly identified as predictors of disease progression in EBV+ IFDCS.

- Surgical resection remains the standard of care for EBV+ IFDCS. The role of chemotherapy or radiotherapy, whether primary, adjuvant or neoadjuvant, is not well described and remains dependent on the combination of patient factors, tumor characteristics and clinical discretion [12]. Immunotherapy targeting programmed death-1/programmed death-ligand 1 presents a theoretical alternative, particularly for unresectable, recurrent, or metastatic EBV+ IFDCS.

- In conclusion, this case highlights the importance of considering granuloma-rich variants of EBV+ IFDCS in the differential diagnosis of hepatic lesions with granulomatous inflammation, particularly in patients with chronic liver disease and concurrent viral infections. The recognition of this rare variant is crucial for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.

DISCUSSION

Ethics Statement

Formal written informed consent was not required with a waiver by the SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB).

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: WQL. Data curation: HGDS, YZ. Writing—original draft: HGDS, YZ. Writing—review & editing: all authors. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding to declare.

- 1. Ge R, Liu C, Yin X, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of inflammatory pseudotumor-like follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014; 7: 2421-9. PubMedPMC

- 2. Yan S, Yue Z, Zhang P, et al. Case report: Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor-like follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: a rare case and review of the literature. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023; 10: 1192998.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 3. Cheuk W, Chan JK, Shek TW, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumorlike follicular dendritic cell tumor: a distinctive low-grade malignant intra-abdominal neoplasm with consistent Epstein-Barr virus association. Am J Surg Pathol 2001; 25: 721-31. PubMed

- 4. Li XQ, Cheuk W, Lam PW, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor-like follicular dendritic cell tumor of liver and spleen: granulomatous and eosinophil-rich variants mimicking inflammatory or infective lesions. Am J Surg Pathol 2014; 38: 646-53. PubMed

- 5. Li Y, Yang X, Tao L, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of EpsteinBarr virus-positive inflammatory follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: extremely wide morphologic spectrum and immunophenotype. Am J Surg Pathol 2023; 47: 476-89. PubMed

- 6. Nie C, Xie X, Li H, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-positive inflammatory follicular dendritic cell sarcoma with significant granuloma: case report and literature review. Diagn Pathol 2024; 19: 34.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 7. Abe K, Kitago M, Matsuda S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated inflammatory pseudotumor variant of follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the liver: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Case Rep 2022; 8: 220.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 8. Choe JY, Go H, Jeon YK, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor-like follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the spleen: a report of six cases with increased IgG4-positive plasma cells. Pathol Int 2013; 63: 245-51. PubMed

- 9. Coffin CM, Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: comparison of clinicopathologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features including ALK expression in atypical and aggressive cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2007; 31: 509-20. PubMed

- 10. Dunleavy K, Roschewski M, Wilson WH. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis and other Epstein-Barr virus associated lymphoproliferative processes. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 2012; 7: 208-15. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 11. Wu H, Liu P, Xie XR, Chi JS, Li H, Xu CX. Inflammatory pseudotumor-like follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: literature review of 67 cases. World J Meta-Anal 2021; 9: 1-11. Article

- 12. Pascariu AD, Neagu AI, Neagu AV, Bajenaru A, Betianu CI. Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor-like follicular dendritic cell tumor: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2021; 15: 410.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Mesenchymal Tumors of the Liver: An Update Review

Joon Hyuk Choi, Swan N. Thung

Biomedicines.2025; 13(2): 479. CrossRef - EBV-positive inflammatory follicular dendritic cell sarcoma occurring in different organs: a case report and literature review

Wenhua Bai, Chunfang Hu, Zheng Zhu

Frontiers in Oncology.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - Spleen EBV-positive inflammatory follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: a case report and literature review

Yi Xiao, Lanlan Li, Xiumei Zhan, Juner Xu, Yewu Chen, Qiuchan Zhao, Yinghao Fu, Xian Luo, Huadi Chen, Hao Xu

Frontiers in Oncology.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - Epstein-Barr virus-positive inflammatory follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the liver: clinical features, imaging findings and potential diagnostic clues

Gui-Ling Huang, Man-Qian Huang, Yu-Ting Zhang, Hui-Ning Huang, Hong-Tao Liu, Xiao-Qing Pei

Abdominal Radiology.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - Epstein‑Barr virus+ inflammatory follicular dendritic cell sarcoma with clonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement: A case report and literature review

Qian Ye, Juan Zhao, Jiao He, Weishan Zhang

Oncology Letters.2025; 31(2): 1. CrossRef - Primary hepatic follicular dendritic cell sarcoma: A case study and literature review

Junjie Zhu, Ying Liang, Li Zhang, Bingqi Li, Danfeng Zheng, Hangyan Wang

Journal of International Medical Research.2025;[Epub] CrossRef

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link-

Cite this Article

Cite this Article

- Cite this Article

-

- Close

- Download Citation

- Close

- Figure

E-submission

E-submission