Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Pathol Transl Med > Volume 60(1); 2026 > Article

-

Review Article

A comprehensive review of ossifying fibromyxoid tumor: insights into its clinical, pathological, and molecular landscape -

Kyriakos Chatzopoulos1

, Antonia Syrnioti1

, Antonia Syrnioti1 , Mohamed Yakoub2

, Mohamed Yakoub2 , Konstantinos Linos2

, Konstantinos Linos2

-

Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine 2026;60(1):6-19.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2025.10.02

Published online: January 14, 2026

1Department of Pathology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

2Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA

- Corresponding author: Konstantinos Linos, MD, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10065, USA Tel: +1-212-639-5905, Fax: +1-212-557-0531, E-mail: linosk@mskcc.org

© The Korean Society of Pathologists/The Korean Society for Cytopathology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 2,025 Views

- 95 Download

Abstract

- Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor (OFMT) is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm first described in 1989. It typically arises in the superficial soft tissues of the extremities as a slow-growing, painless mass. Histologically, it is commonly characterized by a multilobular architecture composed of uniform epithelioid cells embedded in a fibromyxoid matrix, often surrounded by a rim of metaplastic bone. While classic cases are readily identifiable, the tumor's histopathological heterogeneity can mimic a range of benign and malignant neoplasms, posing significant diagnostic challenges. Molecularly, most OFMTs harbor PHF1 rearrangements, commonly involving fusion partners such as EP400, MEAF6, or TFE3. This review underscores the importance of an integrated diagnostic approach–incorporating histopathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular data- to accurately classify OFMT and distinguish it from its mimics. Expanding awareness of its morphologic and molecular spectrum is essential for precise diagnosis, optimal patient management, and a deeper understanding of this enigmatic neoplasm.

- Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor (OFMT) is a rare soft tissue neoplasm of uncertain histogenesis, typically arising in the soft tissues of the extremities and often in the subcutaneous tissue [1]. First described by Enzinger et al. in 1989 [2], OFMT displays a wide spectrum of morphological findings and biological behavior. While typical histopathological presentations usually pose little diagnostic challenge, the tumor’s morphological variability can complicate diagnosis. This includes cases exhibiting chondroid or lipoblastic differentiation [3], clear cell morphology or collagen entrapment [4], which may mimic other soft tissue neoplasms. Furthermore, hypercellular and mitotically active tumors with significant cellular atypia can demonstrate metastatic potential [5], underscoring the importance of accurate and timely diagnosis. The majority of OFMTs have recurrent molecular alterations, most frequently PHF1 rearrangements [6], and molecular pathology can serve as a valuable adjunct in diagnosing challenging cases [4]. This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the clinical, pathological, and molecular characteristics of OFMT, educating the readers on this enigmatic entity.

INTRODUCTION

- Despite the rarity of OFMT, multiple case series have described its clinical and pathologic findings in thorough detail. In most cases, OFMT presents as a long-existing, slow-growing, painless mass, with a median duration of ~4 years before patients seek medical attention and treatment [7]. In the original case series of 59 patients published by Enzinger et al. in 1989 [2], OFMT was diagnosed more frequently in males than females, with age range spanning from 14 to 79 years. In the series of 70 patients published by Folpe and Weiss [5], OFMT was primarily observed in middle-aged adults, with a slight male predominance, and a propensity to arise in the soft tissues of the extremities. These findings were corroborated by a subsequent study of 104 patients from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, which highlighted a median age of 50 years at diagnosis, along with a male-to-female-ratio of 1.5:1 [7], as well as the study by Graham et al on 46 patients with a median age of 52 years and male-to-female ratio of 1.7:1 [8]. Apart from the extremities, OFMT frequently arises in various locations of the head and neck region [9-18]. Intracranial involvement [19,20], occasionally with transcranial extension [21], as well as paraspinal [22] or spinal extradural involvement [23] have been described. Other unusual locations include the retroperitoneum [24], the breast [25], and the genitourinary (GU) tract [26]. Pediatric cases, although uncommon, have been reported [27,28], including a 3-week-old male neonate with a left nasal mass [29].

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION

- OFMT typically presents as a well-circumscribed, ovoid, small soft tissue mass, with a rubbery to firm texture, and a glistening, white cut surface. It often features a peripheral hard shell, which can be appreciated on imaging as irregular bone [7,8,30]. Most tumors are small to medium-sized, with a median size of 3–5 cm, although large tumors measuring up to 17 cm or even 21 cm have been reported [5,7,8]. In the appropriate clinico-radiological setting, this finding can occasionally complicate the differential diagnosis with parosteal osteosarcoma [31]. The tumors are most often subcutaneous, although rarely, they may arise within the skeletal muscle, particularly in the head and neck area [7].

MACROSCOPIC FINDINGS

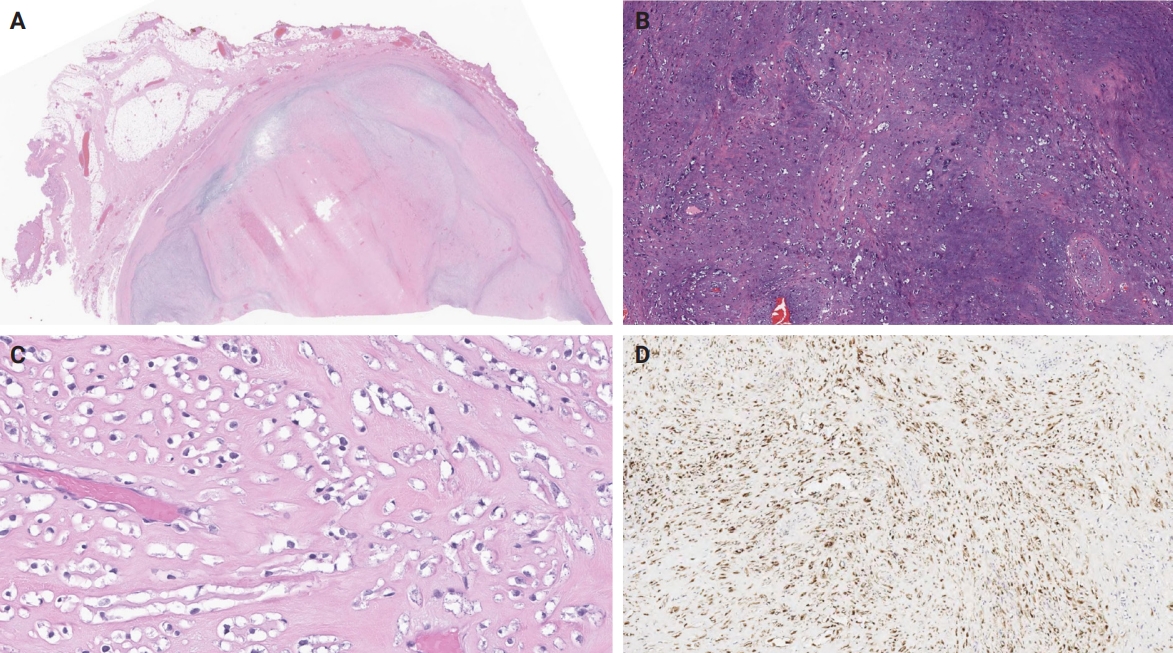

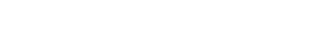

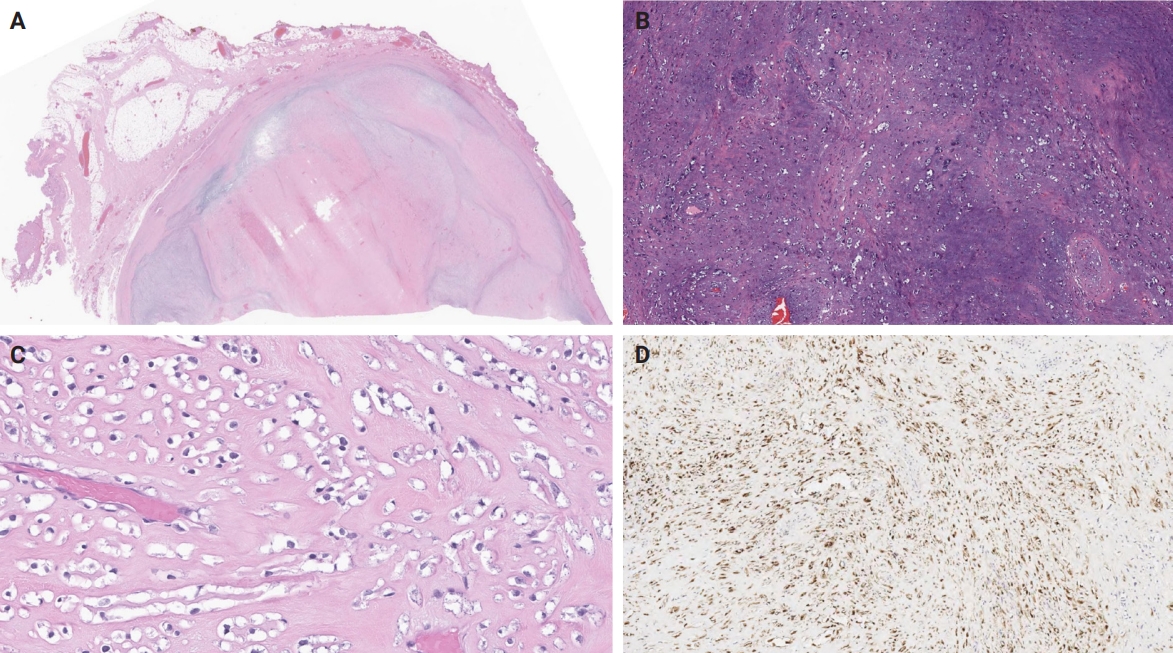

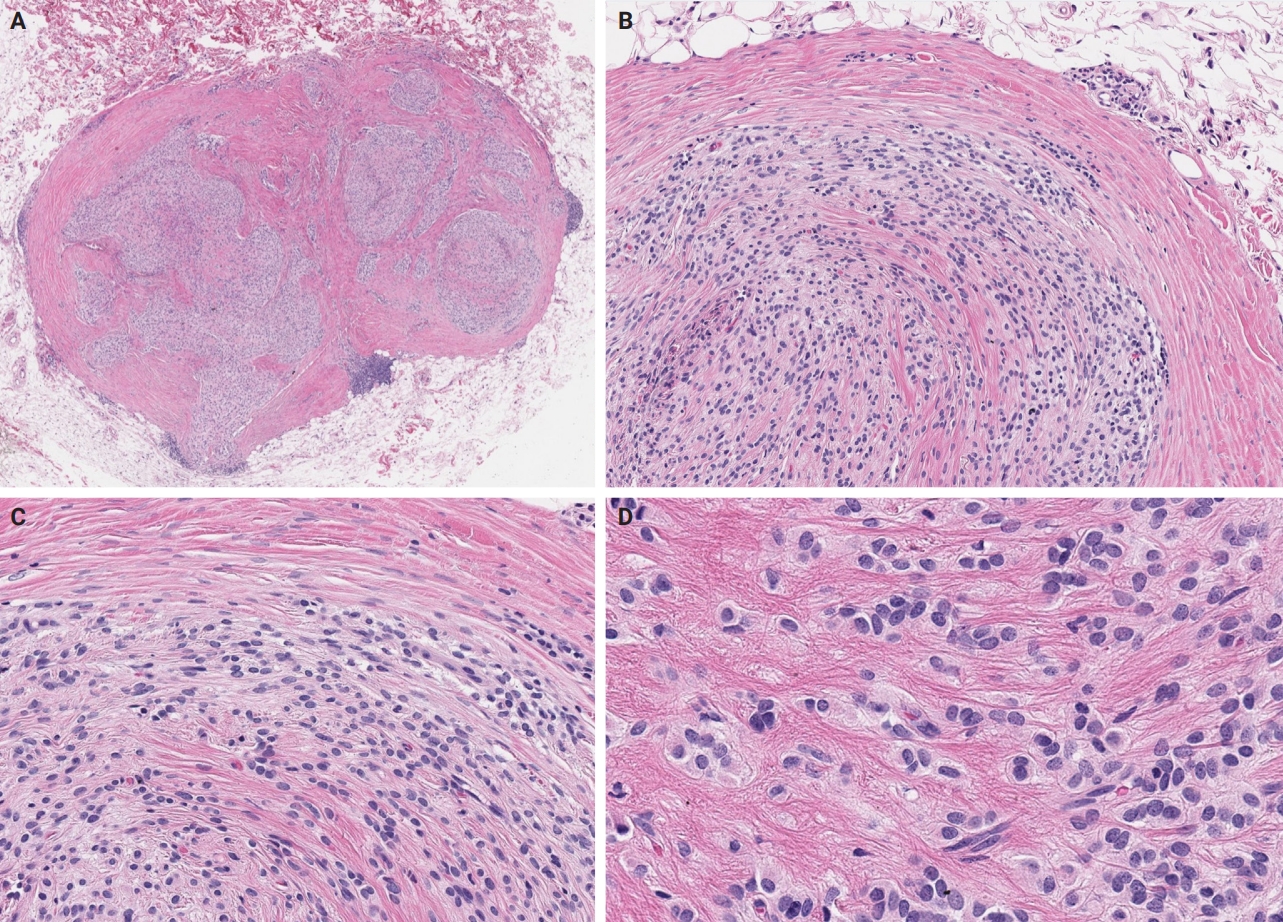

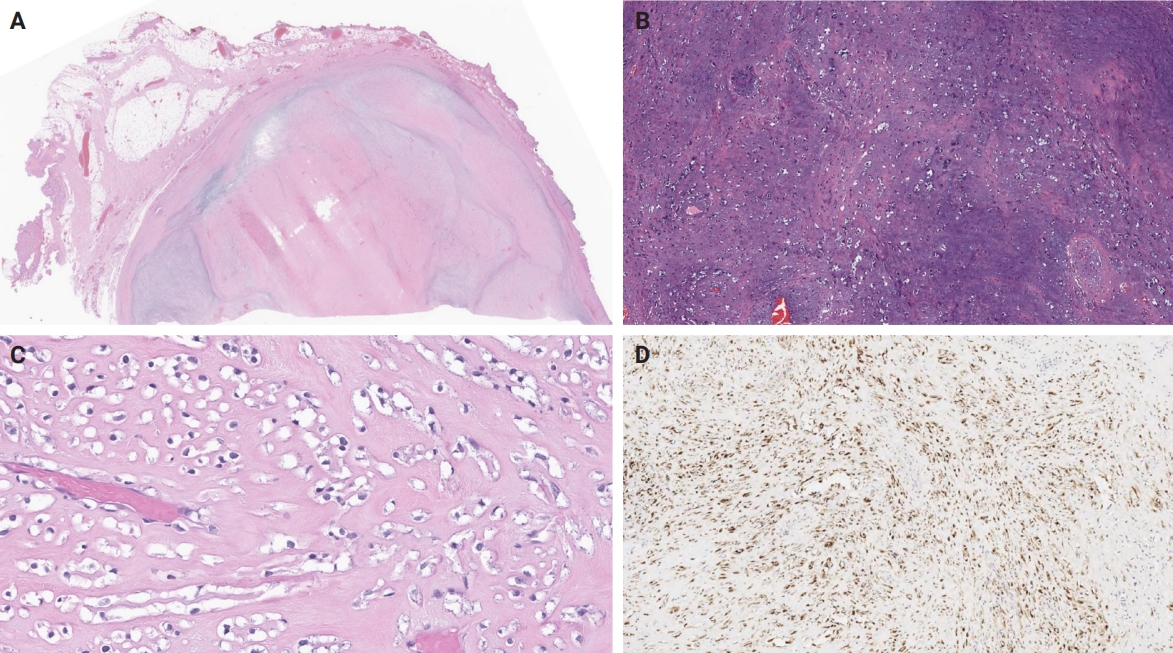

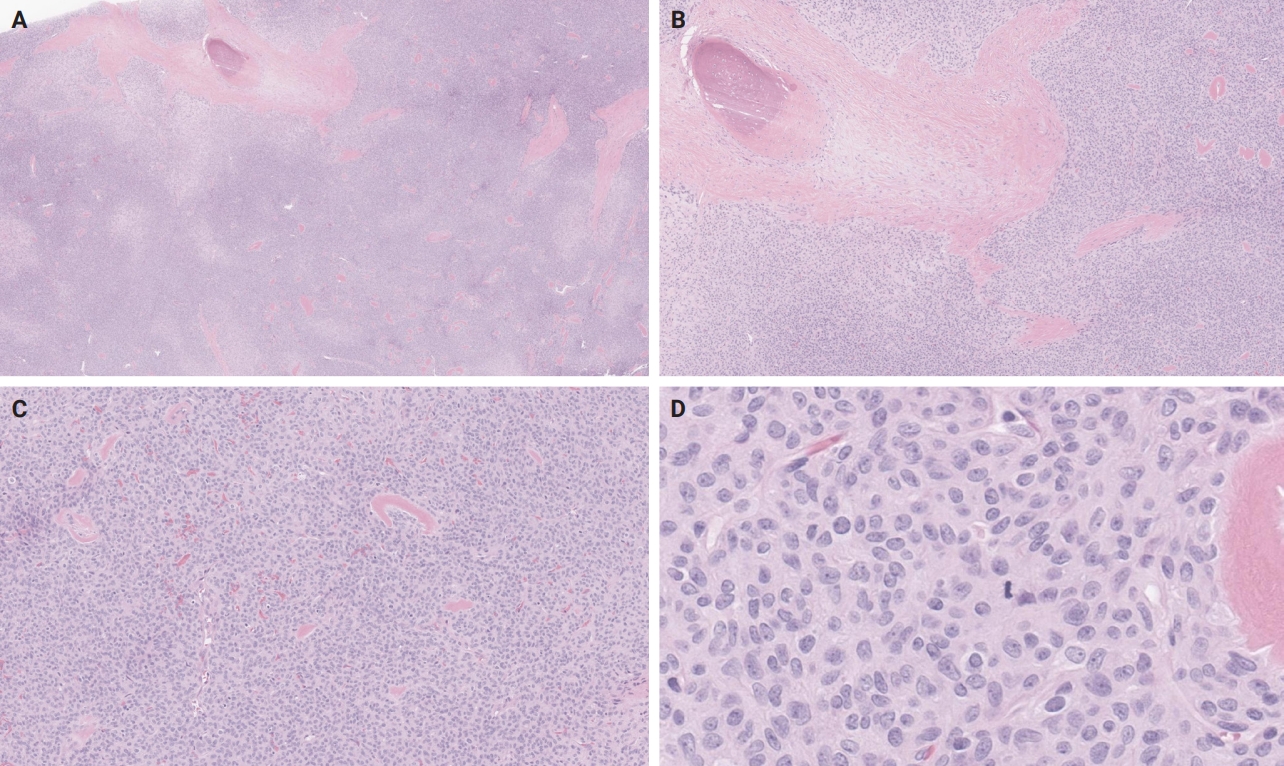

- Microscopically, OFMT exhibits a multilobular architecture, with a pressure effect on the superficial component of the overlying skin, occasionally associated with cutaneous ulceration [7]. The tumor is lined by a pseudocapsule with metaplastic lamellar or woven bone, sometimes interspersed with adipocytes between bony trabeculae, but lacking hematopoietic cells. However, it's worth noting that the absence of the peripheral bone shell is reported in ~25%–40% of OFMT [8,32]. Additionally, osteoid material is commonly observed in central regions of the tumor [33], which raises the possibility of osteosarcoma in the differential diagnosis [34]. Pericapsular aggregates of lymphocytes are not uncommon [5,35]. Within a collagenous or myxoid matrix with perivascular hyalinization, the tumor cells are uniform and epithelioid, featuring pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm, round nuclei with even chromatin distribution, delicate nucleoli, inconspicuous clefts or pseudoinclusions, and low mitotic activity [5,7,35] (Fig. 1).

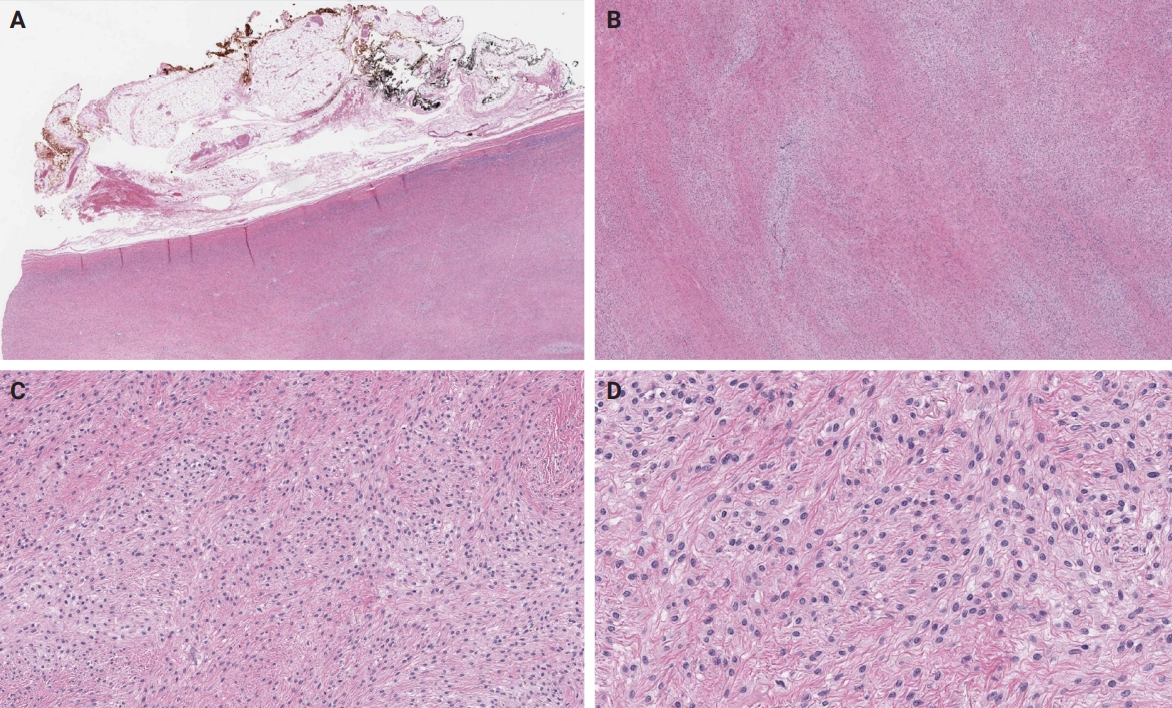

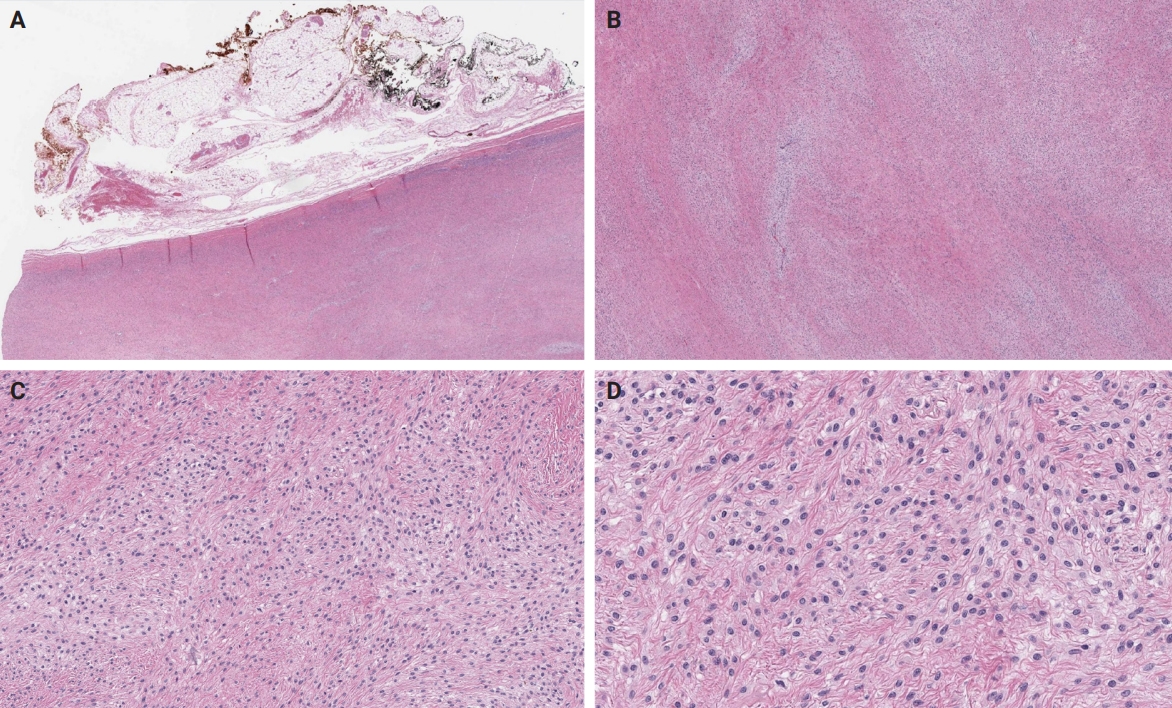

- Unusual findings described in OFMT include breakdown of lamellar bone with osteoclasts, central hemorrhagic infarction [7], satellite microscopic nodules, mucinous microscopic cysts, microcalcification, crushing artifact, and paucity or absence of myxoid matrix, as well as chondroid differentiation (Fig. 2) with atypical binucleated cells [36]. Additional unusual findings are predominance of clear cell morphology, extravasated red blood cells, collagen entrapment and interdigitating fibrocollagenous and fibromyxoid stromal bundles [4] (Figs. 3, 4). A recent study also described two OFMTs with prominent lipoblastic differentiation [3].

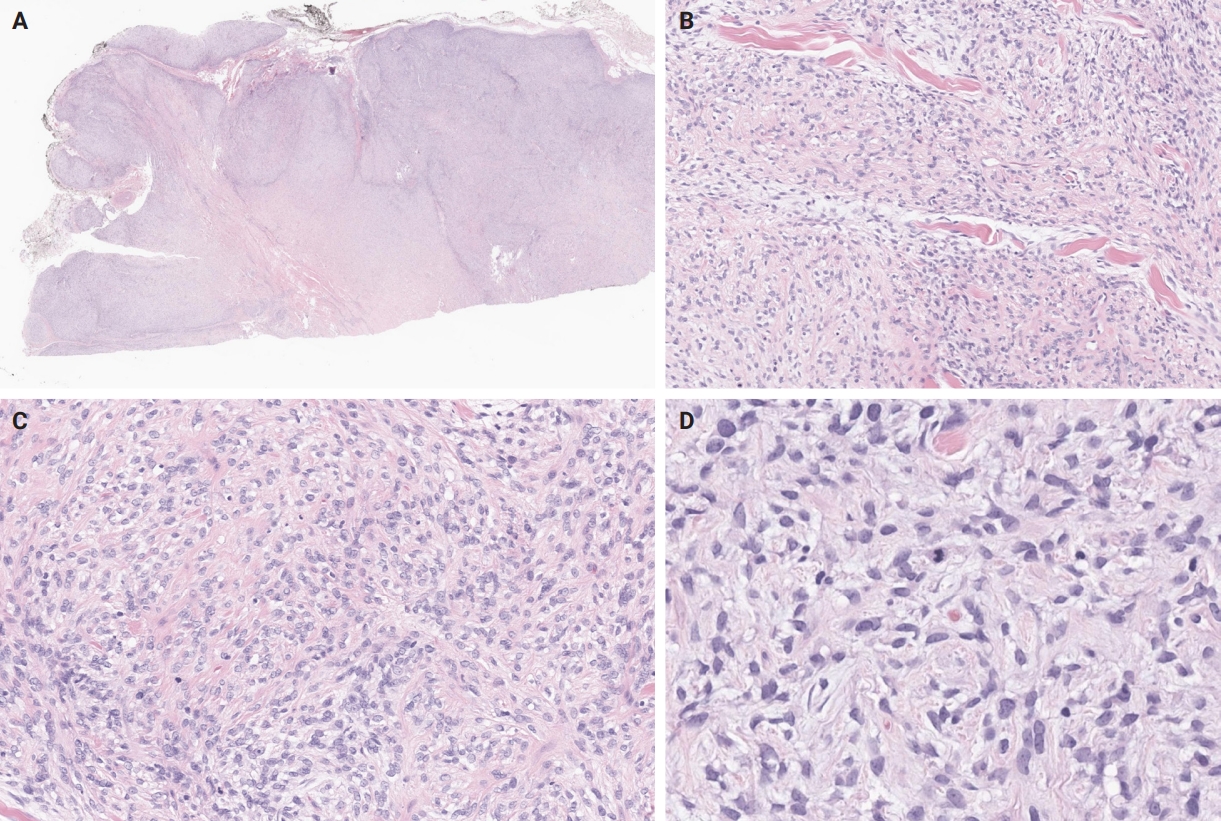

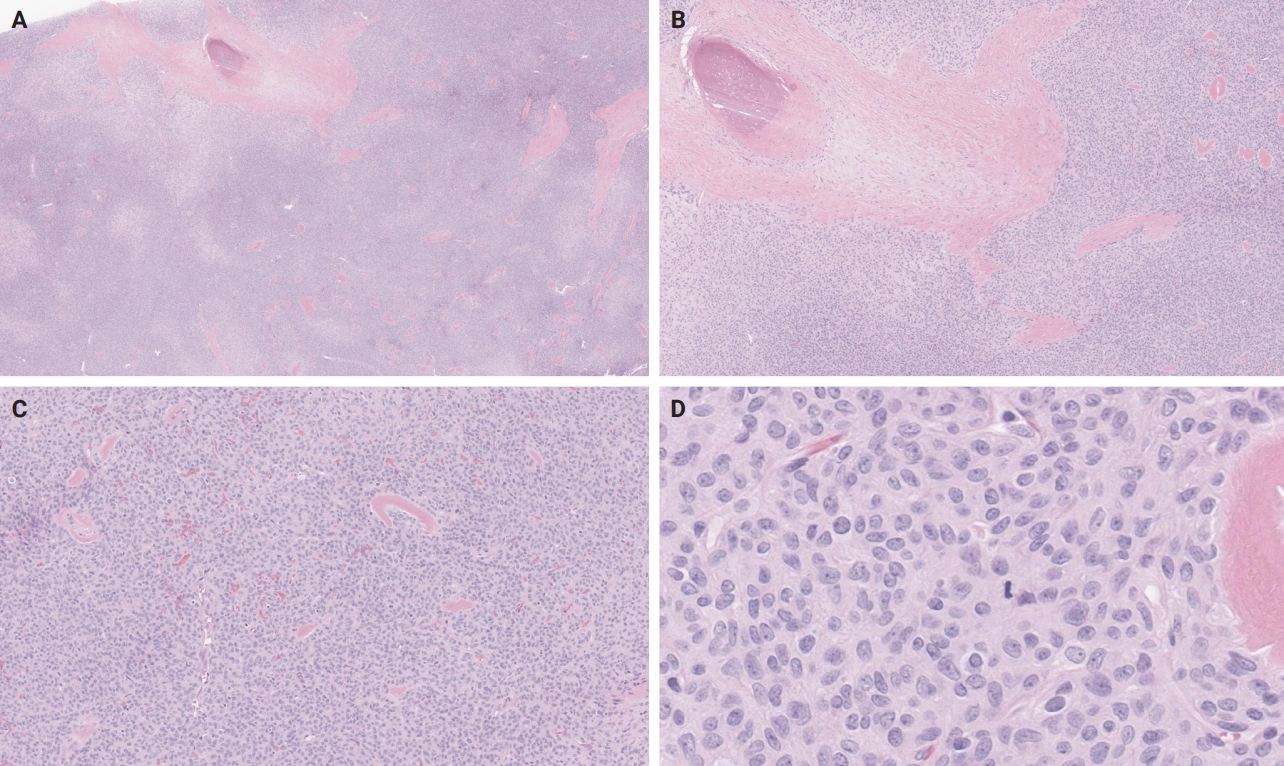

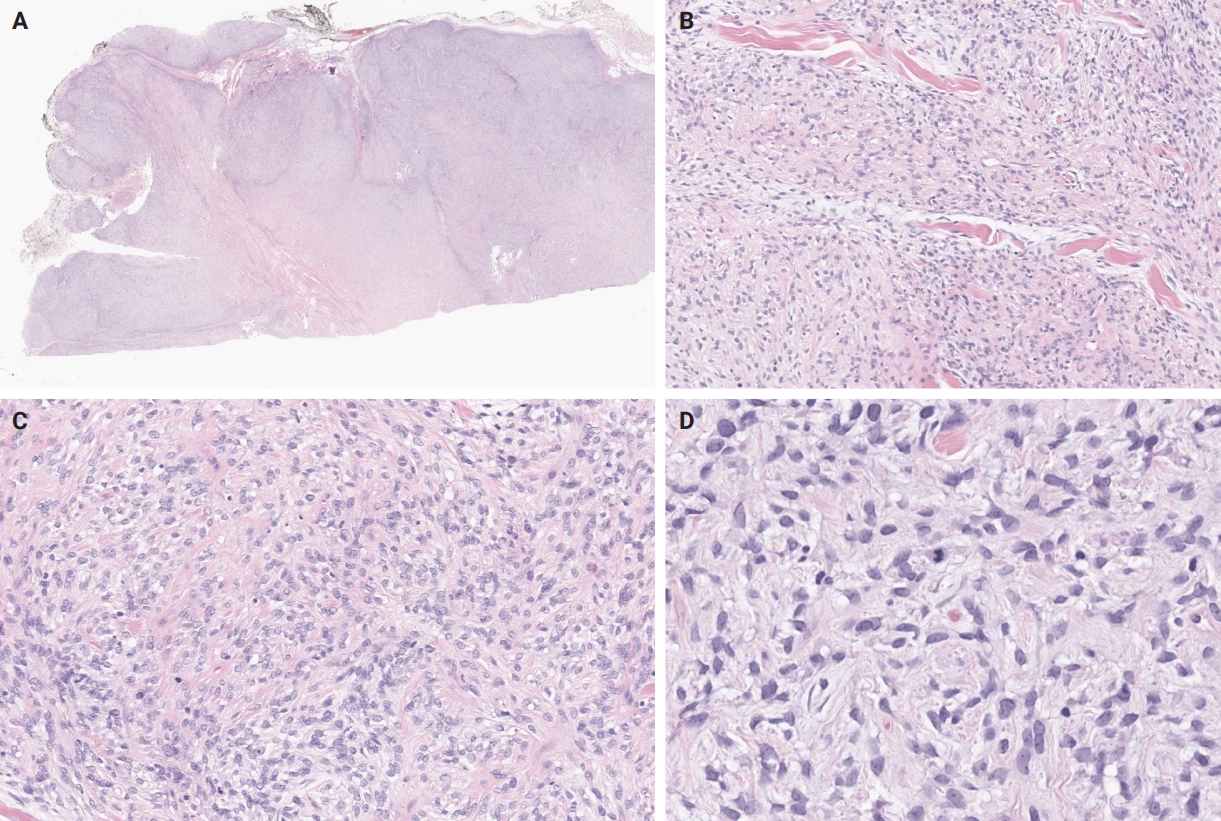

- An OFMT characterized by high nuclear grade or increased cellularity, and mitotic activity exceeding 2 mitoses per 50 high power fields can be classified as malignant [5] (Figs. 5–8). Additionally, necrosis and an infiltrative pattern may be present [8]. Patients with malignant OFMT are more likely to develop distant metastases, most often to the lungs [37]. Although overtly sarcomatous changes in OFMT are uncommon, they have been documented [38], with reported cases including osteosarcoma arising from OFMT after multiple recurrences [39].

MICROSCOPIC FINDINGS

- The histogenesis of OFMT remains enigmatic. Initially it was thought to be a neoplasm of Schwannian origin [40] with possible incomplete neural or cartilaginous differentiation, a hypothesis supported by the commonly observed S100 protein immunoreactivity [7]. However, electron microscopy findings largely resemble those seen in pleomorphic adenomas or myoepithelial tumors [41], including paucity of organelles and aggregates of intermediate filaments with reduplicated basal lamina material [41-43]. Therefore, myoepithelial origin or differentiation is a plausible hypothesis, supported by case reports of tumors displaying intermediate characteristics between OFMT and myoepithelial neoplasms, as discussed below.

HISTOGENESIS

- The diagnosis of OFMT on cytology specimens is very challenging, both because of its rarity and the non-specific cytomorphology of the cellular component [44]. However, the presence of a fine fibrillary [45] or myxoid matrix [46], with occasional rosette-like structures [44,45] and particularly osteoid-like material [47] can guide cytopathologists to include OFMT in the differential diagnosis of a soft tissue mass. In addition, the presence of nuclear atypia, including features such as prominent nucleoli, chromatin clumping and irregular nuclear contours, may raise the possibility of malignant OFMT [46].

CYTOPATHOLOGY

- OFMT typically expresses S100 protein [7,8] and is frequently positive for excitatory amino acid transporter 4 (EAAT4) [8,38], desmin, neurofilament, CD56 [8], CD10 [7], and insulinoma-associated protein 1 (INSM1) [48]. OFMT often displays mosaic expression of integrase interactor 1 (INI1), due to a commonly present underlying alteration of the SMARCB1 gene, as mentioned in detail below [8,38,49]. Transcription factor E3 (TFE3) nuclear expression is typically seen in OFMT harboring a PHF1::TFE3 fusion [50,51].

- Expression of keratins, collagen IV, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), smooth muscle actin (SMA) [7], CD99 [52], MUC4 (not diffuse) [8] or calponin [56] has occasionally been reported, while OFMT is consistently negative for HMB45, CD34 [7], SOX10 [33], and preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma (PRAME) [57]. Interestingly, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor (PR) expression has been described in a PHF1-rearranged OFMT of the breast, which also co-expressed STAT6 [25], as well as in a PHF1-rearranged OFMT of the axillary soft tissues [4], while isolated diffuse PR expression was seen in two OFMTs of the extremities with BCOR and TFE3 rearrangements [51].

- Of note, expression of pan-tropomyosin receptor kinase (pan-TRK) by immunohistochemistry has been reported in BCOR-rearranged OFMT [58,59]. Given the efficacy of targeted neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase (NTRK) inhibition for patients with NTRK-fused tumors [60], this finding is of potential clinical interest. Although the exact mechanism of pan-TRK expression has not been fully elucidated, it seems that it occurs due to underlying NTRK3 mRNA overexpression [58].

- Finally, it is worth mentioning that malignant OFMT can show an atypical immunophenotype, with attenuation or complete absence of S100 protein expression [61]. Absence of S100 expression was also demonstrated in all four GU OFMTs described by Argani et al. [26], two of which were classified as malignant based on mitotic count.

IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY

- The presence of clonal chromosomal alterations such as aneusomies, unbalanced translocations [62] and complex karyotypes [63], including marker chromosomes [64], was highlighted in early studies. Complex karyotypes have been particularly associated with malignant OFMT cases exhibiting metastases [63]. A relatively recurrent finding is hemizygous deletion of chromosome 22 or 22q, leading to hemizygous loss of SMARCB1, an alteration corresponding to the mosaic immunohistochemical pattern of INI1 expression frequently observed, as mentioned above [8]. Another recurrent finding most often seen in atypical and malignant OFMT is loss of the RB1 tumor suppressor gene, observed in almost a third of cases [55].

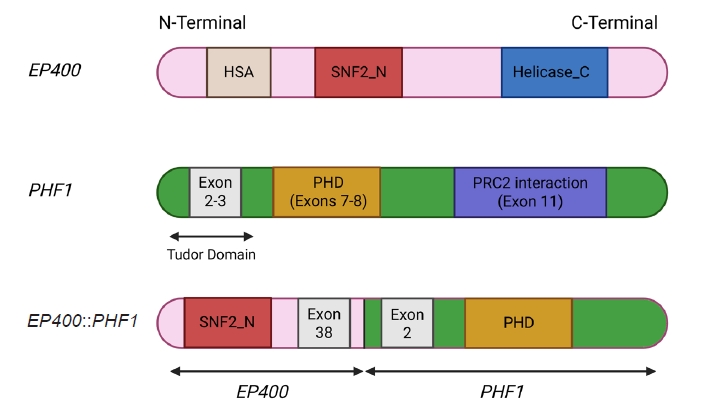

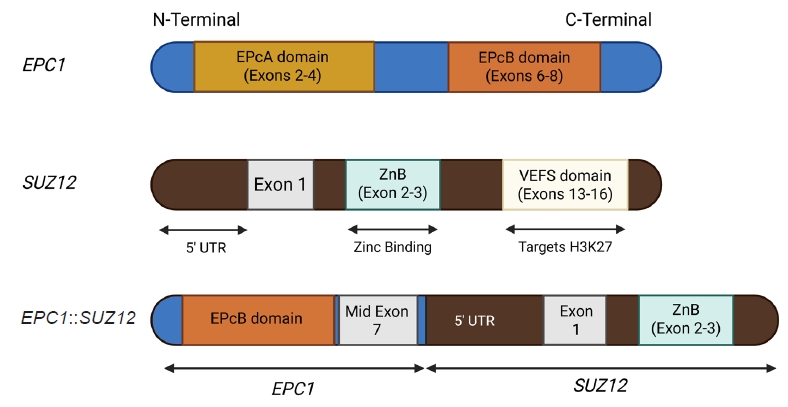

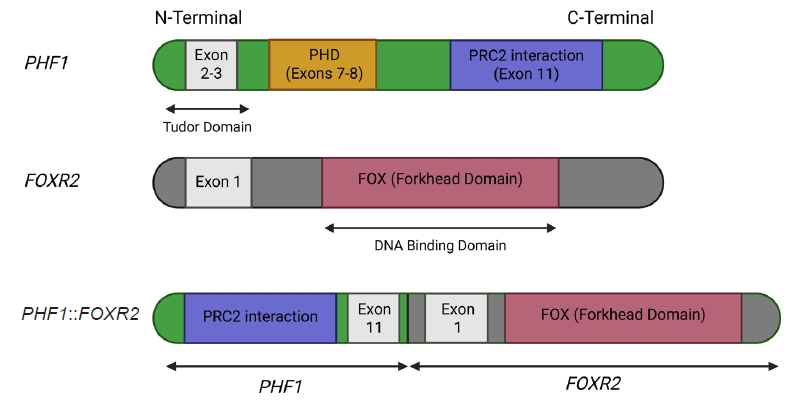

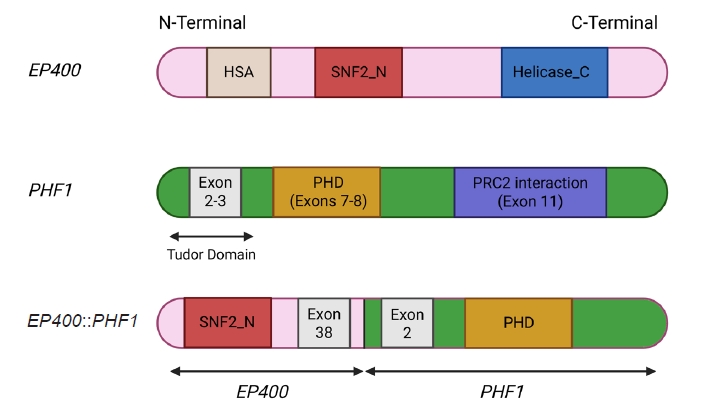

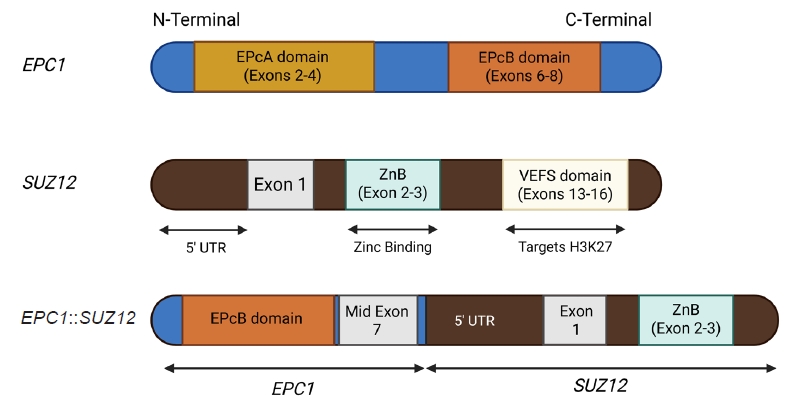

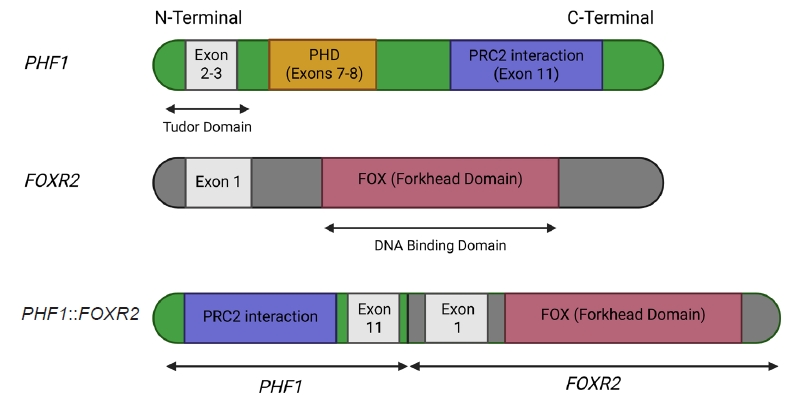

- The molecular hallmark of OFMT is the presence of recurrent rearrangements of PHF1, which are seen in approximately 80%–85% of tumors [6]. The PHF1 gene encodes a protein which interacts with polycomb-repressive complex 2 (PRC2), an important regulator of chromatin structure and developmental gene expression [65], ultimately controlling histone H3K27 methylation status [66]. Rearrangement of PHF1 typically occurs in the form of a reciprocal translocation, resulting in gene fusion, with EP400 being the most common fusion partner (Fig. 4) [67]. Other PHF1 fusion partners include EPC1, MEAF6 [68], TFE3 [69], FOXR1, FOXR2 (Fig. 8) [70], CREBZF [34], TP53 [71], and JAZF1 [3].

- Non-PHF1 fusions have also been described, including MEAF6::SUZ12 [72], EPC1::SUZ12 (Fig. 6) [4], CREBBP::BCORL1, KDM2A::WWTR1 [73], ZC3H7B::BCOR [59], CSMD1::MEAF6 [55], and EPC1::PHC1 [3]. The common denominator of these fusions is that they function as tumor drivers, inducing significant epigenetic changes via histone modification, a process currently regarded as the major molecular mechanism of OFMT pathogenesis [55]. Of note, a non-fused malignant OFMT with a BCOR internal tandem duplication has been reported in a pediatric patient with a lateral neck mass and subsequent local and metastatic recurrences [74].

- Interestingly, certain of the above mentioned fusions, particularly JAZF1::PHF1, EPC1::PHF1, MEAF6::PHF1, ZC3H7::BCOR, and EPC1::SUZ12 [75,76] have been previously described in low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS), a finding explaining why certain OFMT may cluster with ESSs by DNA methylation analysis [4]. The latter fact may limit the utility of DNA methylation assay in the work-up of OFMT.

- Given the frequency of PHF1 rearrangements, a reasonable approach includes morphological assessment with confirmation of PHF1 alteration by break-apart fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) [77]. However, in cases with unusual morphological findings and non-PHF1 rearrangements, the final diagnosis may need to be deferred until molecular testing by next generation sequencing (NGS) is performed [4].

MOLECULAR GENETICS

- The broad spectrum of the differential diagnosis for OFMT often encompasses myoepithelial neoplasms [78]. In challenging cases, testing for EWSR1 rearrangements in these neoplasms can provide valuable insights. However, it's essential to acknowledge that EWSR1 rearrangements are detected in only around 50% of soft tissue myoepithelial neoplasms [79], making the test informative when positive, but less conclusive when negative.

- The most frequent pitfall in the differential diagnosis of OFMT is low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) [80]. Also known as “Evans tumor” [81], LGFMS is a low-grade sarcoma arising in the extremities of young adults, although as many as 20% of cases occur in patients younger than 18 years old. It consists of spindle to epithelioid cells arranged in alternating hyalinized and myxoid areas, with occasional hyaline rosettes [82]. These morphologic features, along with lack of S100 expression and strong and diffuse MUC4 positivity, usually suffice for distinguishing LGFMS from OFMT. Molecular detection of the characteristic FUS::CREB3L2 or EWSR1::CREB3L1 fusions confirms the diagnosis of LGFMS in the appropriate morphologic context [83].

- Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma (SEF) or hybrid SEF-LGFMS tumors are also frequently included in the differential diagnosis. SEF is a rare aggressive variant of fibrosarcoma, characterized by small epithelioid cells arranged in cords and nests within a densely sclerotic stroma [84]. However, unlike OFMT, SEF primarily arises in deep soft tissues and lacks S100 expression [85]. The diagnosis of SEF can be confirmed through molecular studies that identify the characteristic EWSR1::CREB3L1 fusion [86].

- The differential diagnosis also includes the newly described YAP1::KMTA2-rearranged sarcoma, an aggressive soft tissue malignancy, notorious for its propensity to mimic benign or low-grade neoplasms, such as schwannoma, fibromatosis or LGFMS [87]. Initially thought to represent a MUC4-negative subtype of SEF, the identification of recurrent YAP1 and KMT2A rearrangements [88,89], along with distinctive morphologic features [89] and a unique DNA methylation profile [87], has established YAP1::KMT2A rearranged sarcoma as a novel entity. These tumors usually exhibit an infiltrative growth pattern with areas of variable cellularity, where monomorphic epithelioid or bland, fibroma-like spindle cells are embedded in a densely collagenous matrix. Mitotic activity is generally low and high-grade features, such as necrosis are usually absent [89]. Immunohistochemically, these tumors are consistently negative for MUC4 and usually negative for S100 protein, but may show variable EMA or CD34 expression [86]. Despite its deceptively low-grade histomorphology, YAP1::KMT2A-rearranged sarcoma can follow an aggressive clinical course, with local recurrence and metastatic disease developing in up to 50% of patients [86].

- Other entities to consider in the differential diagnosis include schwannoma [90], malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) [78], extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (EMC) [48], and extraskeletal osteosarcoma [78]. Schwannoma arises from the peripheral nerve sheath and is characteristically strongly and diffusely positive for S100 protein, in contrast to OFMT, where S100 expression may be weak or absent. Schwannomas also lack the peripheral ossification and cytomorphologic features typical of OFMT [90]. MPNST typically arises in deep soft tissues, often in association with major nerves, and does not exhibit peripheral ossification. While MPNST may show attenuated S100 positivity, it can also express other neural markers such as neurofilament and GFAP [78]. Importantly, loss of H3K27me3 expression—frequently seen in MPNST—can help distinguish it from OFMT, in which H3K27me3 expression is consistently retained [91,92]. EMC is characterized by a lobular architecture with fibrous septa and uniform tumor cells showing eosinophilic cytoplasm, occasional spindling, and inconspicuous nucleoli in a myxoid background. EMC typically expresses INSM1, synaptophysin, and sometimes other neuroendocrine or neural markers such as chromogranin, PGP9.5, microtubule-associated protein 2, class III β-tubulin, and peripherin [48]. Genetically, EMC is defined by NR4A3 rearrangements, most commonly with EWSR1, but also involving partners such as TAF15, TCF12, TFG, FUS, HSPA8, LSM14A, or SMARCA2 [48]. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma is exceedingly rare in the skin or subcutis and typically represents metastatic disease, making clinical history essential. Helpful distinguishing features include lack of S100 expression and the presence of marked nuclear atypia [78].

- Notably, primary bone OFMT has also been described, which may be extremely challenging to distinguish from osteosarcoma [93]. In tumors with lipoblastic differentiation, distinction from benign and malignant lipomatous tumors such as chondroid lipoma or myxoid liposarcoma can be challenging [3]. The differential diagnosis can be particularly challenging in tumors with uncommon microscopic features, where the final diagnosis can be confidently rendered only by confirming a characteristic molecular alteration [4].

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

- Diagnosing OFMT requires an integrative approach, as the tumor's morphologic and immunophenotypic spectrum is broad and overlaps with several benign and malignant entities. In classic presentations—characterized by uniform ovoid cells embedded in a fibromyxoid matrix and surrounded by a peripheral shell of metaplastic bone—the diagnosis may be straightforward, particularly when supported by strong S100 protein and desmin expression. However, in atypical or malignant variants, these features may be attenuated or absent. For instance, malignant OFMTs frequently lack ossification, exhibit increased cellularity and mitotic activity, and may show reduced or completely lost S100 expression. Ancillary studies are essential in such cases. FISH is widely used and can detect gene rearrangements or amplifications in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue with good sensitivity, but it is restricted to one locus per assay and, in the case of break-apart probes, cannot identify the fusion partner. Furthermore, cryptic or complex rearrangements may go undetected. Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) offers high sensitivity and relatively low cost for detecting known fusion transcripts, but it requires prior knowledge of the partner genes and thus cannot identify novel fusions. Targeted RNA sequencing and broader NGS panels overcome these limitations by interrogating multiple loci simultaneously, allowing both confirmation of established fusions and discovery of novel ones. Although more resource-intensive, NGS has emerged as the most reliable method for characterizing OFMT at the molecular level, particularly in diagnostically challenging cases [94].

- In clinical practice, the diagnostic work-up of a suspected OFMT typically begins with a panel of broad immunohistochemical stains, including S100, SOX10, desmin, SMA, and a broad-spectrum cytokeratin. In tumors with classic morphology, the combination of S100 and desmin positivity is generally sufficient to establish a confident diagnosis. In cases with very suggestive morphology but incomplete immunophenotypic support—for example, when S100 or desmin expression is weak or focal—PHF1 break-apart FISH is the logical next step, as approximately 80%–85% of OFMTs harbor PHF1 rearrangements. If PHF1 testing is negative but the pretest probability remains high, RT-PCR, targeted RNA sequencing or broad-panel NGS can help identify rarer fusions, such as CREBBP::BCORL1, EPC1::SUZ12, or ZC3H7B::BCOR amongst others.

- In atypical or malignant cases, where classic immunohistochemical markers such as S100 and desmin are diminished or absent, a diagnosis of OFMT may still be appropriate if the tumor contains areas reminiscent of conventional OFMT. In such instances, PHF1 FISH remains useful. However, in malignant tumors that lack both morphologic and immunophenotypic features suggestive of OFMT, comprehensive molecular testing via NGS is often the only practical means of confirming the diagnosis.

- Emerging evidence supports a correlation between specific gene fusions and atypical or malignant histologic features of OFMT. In a synthesis of reported cases across the literature, approximately 26 OFMTs with non-PHF1 fusions or PHF1 fusions involving uncommon partners (e.g., TP53, FOXR1/2, CREBZF, ZC3H7B, EPC1) have been compiled and analyzed. Of these, 18 tumors (69%) were classified as atypical or malignant, indicating a strong association between rare fusion events and aggressive histologic behavior. Moreover, certain fusion types—such as TP53::PHF1, PHF1::FOXR2, ZC3H7B::BCOR, and EPC1::SUZ12—have been reported almost exclusively in malignant cases, further supporting their potential as molecular indicators of high-grade disease. While these rare fusions do not inherently define malignancy, their frequent occurrence in morphologically aggressive tumors suggests they may play a role in driving dedifferentiation or loss of canonical OFMT features.

- These atypical/malignant variants also tend to show marked loss of conventional immunophenotypic markers. In the pooled dataset, S100 expression was retained in only four of 15 cases (27%), often in a focal or patchy distribution, and desmin was expressed in just two of 14 cases (14%). In contrast, classic OFMTs show S100 positivity in ~70% and desmin in ~50% of cases. Additionally, the characteristic peripheral ossified shell was frequently absent in these high-grade tumors, further complicating diagnosis.

- Together, these findings highlight the importance of recognizing non-classic morphologic and immunohistochemical presentations and maintaining a low threshold for molecular testing—especially in tumors lacking both classic architecture and marker expression [71].

PRACTICAL DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

- OFMT is treated surgically with local marginal or wide excision and rarely amputation, particularly when a large tumor arises on a digit [7]. Local recurrence is more likely to occur in patients whose tumors show increased mitotic activity [7]. Tumors fulfilling the microscopic criteria of malignancy, should be regarded as sarcomas for treatment purposes, as they tend to display more aggressive clinical behavior, including the potential for distant metastasis [5,95]. These patients may be candidates for adjuvant radiation therapy, particularly after being diagnosed with local recurrence [5]. Similarly, patients with metastatic disease may be eligible for chemotherapy [96]. When malignant OFMT metastasizes, it typically spreads to the lung [8,37,96], although unusual locations such as the thyroid gland have been reported [97].

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

- OFMT is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm that can occasionally complicate the differential diagnosis of a soft tissue mass, leading to diagnostic uncertainty. Given that certain tumors behave in a clinically aggressive manner, pathologists should consider OFMT in the differential diagnosis of an unusual soft tissue tumor and triage cases for molecular testing where appropriate, as rendering an accurate diagnosis is the cornerstone of effective patient management.

CONCLUSION

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: KL. Data curation: all authors. Formal analysis: all authors. Funding acquisition: KL. Investigation: all authors. Methodology: all authors. Project administration: KL. Resources: KL. Supervision: KL. Validation: KL. Writing—original draft: KC. Writing—review & editing: all authors. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by MSK NIH Funded Grant# P30 CA08748.

- 1. Endo M, Miettinen M, Mertens F. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed. WHO classification of tumours: soft tissue and bone tumours. 5th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2020; 274-6.

- 2. Enzinger FM, Weiss SW, Liang CY. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts: a clinicopathological analysis of 59 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1989; 13: 817-27. ArticlePubMed

- 3. Klubickova N, Billings S, Dermawan JK, Molligan JF, Fritchie K. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumours with lipomatous and cartilaginous differentiation: a diagnostic pitfall. Histopathology 2025; 86: 891-9. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 4. Syrnioti A, Chatzopoulos K, Kerr DA, et al. A potential conundrum in dermatopathology: molecularly confirmed superficial ossifying fibromyxoid tumors with unusual histomorphologic findings and a novel fusion. Virchows Arch 2024; 485: 1063-73. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 5. Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts: a clinicopathologic study of 70 cases with emphasis on atypical and malignant variants. Am J Surg Pathol 2003; 27: 421-31. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Pozas J, Thway K, Lindsay D, et al. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumours: a case series. Eur J Cancer 2025; 217: 115229.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Miettinen M, Finnell V, Fetsch JF. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 104 cases with long-term follow-up and a critical review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 2008; 32: 996-1005. ArticlePubMed

- 8. Graham RP, Dry S, Li X, et al. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts: a clinicopathologic, proteomic, and genomic study. Am J Surg Pathol 2011; 35: 1615-25. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Park DJ, Miller NR, Green WR. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of the orbit. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2006; 22: 87-91. ArticlePubMed

- 10. Blum A, Back W, Naim R, Hormann K, Riedel F. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of the nasal septum. Auris Nasus Larynx 2006; 33: 325-7. ArticlePubMed

- 11. Tanna N, Chadha N, Sharma RR, Goodman JF, Sadeghi N. Malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of the parapharyngeal space. Ear Nose Throat J 2012; 91: E15-7. ArticlePDF

- 12. Perez-de-Oliveira ME, Morais TM, Lopes MA, de Almeida OP, van Heerden WF, Vargas PA. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of the oral cavity: rare case report and long-term follow-up. Autops Case Rep 2021; 11: e2020216. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Ohta K, Taki M, Ogawa I, et al. Malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of the tongue: case report and review of the literature. Head Face Med 2013; 9: 16.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 14. Sharif MA, Mushtaq S, Mamoon N, Khadim MT. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of oral cavity. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2008; 18: 181-2. PubMed

- 15. Nonaka CF, Pacheco DF, Nunes RP, Freitas Rde A, Miguel MC. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor in the mandibular gingiva: case report and review of the literature. J Periodontol 2009; 80: 687-92. ArticlePubMed

- 16. Mollaoglu N, Tokman B, Kahraman S, Cetiner S, Yucetas S, Uluoglu O. An unusual presentation of ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of the mandible: a case report. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2006; 31: 136-8. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 17. Titsinides S, Nikitakis NG, Tasoulas J, Daskalopoulos A, Goutzanis L, Sklavounou A. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of the retromolar trigone: a case report and systematic review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol 2017; 25: 526-32. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 18. Mashkova TA, Panchenko IG, Maltsev AB, Shaposhnikova IV. A clinical observation of laryngeal ossifying fibromyxoid tumor. Vestn Otorinolaringol 2021; 86: 82-4. ArticlePubMed

- 19. Dhawan S, Lal T, Pandey PN, Saran R, Singh A. Synchronous occurrence of colloid cyst with intracranial ossifying fibromyxoid tumor masquerading as meningioma. Cureus 2020; 12: e10662. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 20. Beyer S, Sebastian NT, Prasad RN, et al. Malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of the brain treated with post-operative fractionated stereotactic radiation therapy: a case report and literature review. Surg Neurol Int 2021; 12: 588.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 21. Hachmann JT, Graham RS. Malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of the calvaria: illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons 2021; 2: CASE21346.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 22. Sangala JR, Park P, Blaivas M, Lamarca F. Paraspinal malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumor with spinal involvement. J Clin Neurosci 2010; 17: 1592-4. ArticlePubMed

- 23. Lu Q, Ho CL. A case of an 82-year-old man with a spinal extradural malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumor. Am J Case Rep 2023; 24: e939408. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 24. Motoyama T, Ogose A, Watanabe H. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of the retroperitoneum. Pathol Int 1996; 46: 79-83. ArticlePubMed

- 25. Gajdzis P, Lae M, Choussy O, Lavigne M, Klijanienko J. Fine-needle aspiration features of ossifying fibromyxoid tumor in the breast: a case report and literature review. Diagn Cytopathol 2019; 47: 711-5. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 26. Argani P, Dickson BC, Gross JM, Matoso A, Baraban E, Antonescu CR. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of the genitourinary tract: report of 4 molecularly confirmed cases of a diagnostic pitfall. Am J Surg Pathol 2023; 47: 709-16. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 27. Aminudin CA, Sharaf I, Hamzaini AH, Salmi A, Aishah MA. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumour in a child. Med J Malaysia 2004; 59 Suppl F: 49-51. PubMed

- 28. Ijiri R, Tanaka Y, Misugi K, Sekido K, Nishi T. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts in a child: a case report. J Pediatr Surg 1999; 34: 1294-6. ArticlePubMed

- 29. Al-Mazrou KA, Mansoor A, Payne M, Richardson MA. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of the ethmoid sinus in a newborn: report of a case and literature review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2004; 68: 225-30. ArticlePubMed

- 30. Schaffler G, Raith J, Ranner G, Weybora W, Jeserschek R. Radiographic appearance of an ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts. Skeletal Radiol 1997; 26: 615-8. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 31. Ogose A, Otsuka H, Morita T, Kobayashi H, Hirata Y. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor resembling parosteal osteosarcoma. Skeletal Radiol 1998; 27: 578-80. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 32. Schneider N, Fisher C, Thway K. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor: morphology, genetics, and differential diagnosis. Ann Diagn Pathol 2016; 20: 52-8. ArticlePubMed

- 33. Carter CS, Patel RM. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor: a review with emphasis on recent molecular advances and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2019; 143: 1504-12. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 34. Sharma AE, Dermawan JK, Sherrod AE, Chopra S, Maki RG, Antonescu CR. When molecular outsmarts morphology: malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumors masquerading as osteosarcomas, including a novel CREBZF::PHF1 fusion. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2024; 63: e23206. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 35. WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. WHO classification of tumours: soft tissue and bone tumours. 5th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2020.

- 36. Zamecnik M, Michal M, Simpson RH, et al. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts: a report of 17 cases with emphasis on unusual histological features. Ann Diagn Pathol 1997; 1: 73-81. ArticlePubMed

- 37. Sarraj A, Duarte J, Dominguez L, Pun YW. Resection of metastatic pulmonary lesion of ossifying fibromyxoid tumor extending into the left atrium and ventricle via pulmonary vein. Eur J Echocardiogr 2007; 8: 384-6. ArticlePubMed

- 38. Dantey K, Schoedel K, Yergiyev O, McGough R, Palekar A, Rao UN. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor: a study of 6 cases of atypical and malignant variants. Hum Pathol 2017; 60: 174-9. ArticlePubMed

- 39. Shelekhova KV, Kazakov DV, Michal M. Extraosseous osteosarcoma arising in recurrent ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft tissue: a case report. Arkh Patol 2013; 75: 24-8.

- 40. Donner LR. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts: evidence supporting Schwann cell origin. Hum Pathol 1992; 23: 200-2. ArticlePubMed

- 41. Min KW, Seo IS, Pitha J. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor: modified myoepithelial cell tumor? Report of three cases with immunohistochemical and electron microscopic studies. Ultrastruct Pathol 2005; 29: 535-48. ArticlePubMed

- 42. Miettinen M. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts: additional observations of a distinctive soft tissue tumor. Am J Clin Pathol 1991; 95: 142-9. ArticlePubMed

- 43. Hirose T, Shimada S, Tani T, Hasegawa T. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor: invariable ultrastructural features and diverse immunophenotypic expression. Ultrastruct Pathol 2007; 31: 233-9. ArticlePubMed

- 44. Goyal P, Sehgal S, Agarwal R, Singh S, Gupta R, Kumar A. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor: diagnostic challenge for a cytopathologist. Cytojournal 2012; 9: 17.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 45. Lax S, Langsteger W. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor misdiagnosed as follicular neoplasia: a case report. Acta Cytol 1997; 41: 1261-4. ArticlePubMed

- 46. Minami R, Yamamoto T, Tsukamoto R, Maeda S. Fine needle aspiration cytology of the malignant variant of ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts: a case report. Acta Cytol 2001; 45: 745-55. ArticlePubMed

- 47. Mohanty SK, Srinivasan R, Rajwanshi A, Vasishta RK, Vignesh PS. Cytologic diagnosis of ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft tissue: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol 2004; 30: 41-5. ArticlePubMed

- 48. Yoshida A, Makise N, Wakai S, Kawai A, Hiraoka N. INSM1 expression and its diagnostic significance in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Mod Pathol 2018; 31: 744-52. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 49. Tajima S, Koda K. Atypical ossifying fibromyxoid tumor unusually located in the mediastinum: report of a case showing mosaic loss of INI-1 expression. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015; 8: 2139-45. PubMedPMC

- 50. Suurmeijer AJ, Song W, Sung YS, et al. Novel recurrent PHF1-TFE3 fusions in ossifying fibromyxoid tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2019; 58: 643-9. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 51. Linos K, Kerr DA, Baker M, et al. Superficial malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumors harboring the rare and recently described ZC3H7B-BCOR and PHF1-TFE3 fusions. J Cutan Pathol 2020; 47: 934-45. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 52. Miliaras D, Meditskou S, Ketikidou M. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor may express CD56 and CD99: a case report. Int J Surg Pathol 2007; 15: 437-40. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 53. Sudarshan D, Avvakumov N, Lalonde ME, et al. Recurrent chromosomal translocations in sarcomas create a megacomplex that mislocalizes NuA4/TIP60 to polycomb target loci. Genes Dev 2022; 36: 664-83. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 54. Przybyl J, Kidzinski L, Hastie T, Debiec-Rychter M, Nusse R, van de Rijn M. Gene expression profiling of low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma indicates fusion protein-mediated activation of the Wnt signaling pathway. Gynecol Oncol 2018; 149: 388-93. ArticlePubMed

- 55. Hofvander J, Jo VY, Fletcher CD, et al. PHF1 fusions cause distinct gene expression and chromatin accessibility profiles in ossifying fibromyxoid tumors and mesenchymal cells. Mod Pathol 2020; 33: 1331-40. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 56. Squillaci S, Tallarigo F, Cazzaniga R, Capitanio A. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor with atypical histological features: a case report. Pathologica 2009; 101: 248-52. PubMed

- 57. Cammareri C, Beltzung F, Michal M, et al. PRAME immunohistochemistry in soft tissue tumors and mimics: a study of 350 cases highlighting its imperfect specificity but potentially useful diagnostic applications. Virchows Arch 2023; 483: 145-56. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 58. Kao YC, Sung YS, Argani P, et al. NTRK3 overexpression in undifferentiated sarcomas with YWHAE and BCOR genetic alterations. Mod Pathol 2020; 33: 1341-9. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 59. Linos K, Kerr DA, Sumegi J, Bridge JA. Pan-Trk immunoexpression in a superficial malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumor with ZC3H7B-BCOR fusion: A potential obfuscating factor in the era of targeted therapy. J Cutan Pathol 2021; 48: 340-2. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 60. Farago AF, Demetri GD. Larotrectinib, a selective tropomyosin receptor kinase inhibitor for adult and pediatric tropomyosin receptor kinase fusion cancers. Future Oncol 2020; 16: 417-25. ArticlePubMed

- 61. Foster-Davies H, Jessop ZM, Clancy RM, et al. Reduced S100 protein expression in malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumors: a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2021; 9: e3482. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 62. Sovani V, Velagaleti GV, Filipowicz E, Gatalica Z, Knisely AS. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts: report of a case with novel cytogenetic findings. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2001; 127: 1-6. ArticlePubMed

- 63. Nishio J, Iwasaki H, Ohjimi Y, et al. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts. Cytogenetic findings. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2002; 133: 124-8. ArticlePubMed

- 64. Kawashima H, Ogose A, Umezu H, et al. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts with clonal chromosomal aberrations. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2007; 176: 156-60. ArticlePubMed

- 65. Gebre-Medhin S, Nord KH, Moller E, et al. Recurrent rearrangement of the PHF1 gene in ossifying fibromyxoid tumors. Am J Pathol 2012; 181: 1069-77. ArticlePubMed

- 66. Sarma K, Margueron R, Ivanov A, Pirrotta V, Reinberg D. Ezh2 requires PHF1 to efficiently catalyze H3 lysine 27 trimethylation in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 2008; 28: 2718-31. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 67. Endo M, Kohashi K, Yamamoto H, et al. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor presenting EP400-PHF1 fusion gene. Hum Pathol 2013; 44: 2603-8. ArticlePubMed

- 68. Antonescu CR, Sung YS, Chen CL, et al. Novel ZC3H7B-BCOR, MEAF6-PHF1, and EPC1-PHF1 fusions in ossifying fibromyxoid tumors: molecular characterization shows genetic overlap with endometrial stromal sarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2014; 53: 183-93. ArticlePubMed

- 69. Zou C, Ru GQ, Zhao M. A PHF1-TFE3 fusion atypical ossifying fibromyxoid tumor with prominent collagenous rosettes: case report with a brief review. Exp Mol Pathol 2021; 123: 104686.ArticlePubMed

- 70. Srivastava P, Zilla ML, Naous R, et al. Expanding the molecular signatures of malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumours with two novel gene fusions: PHF1::FOXR1 and PHF1::FOXR2. Histopathology 2023; 82: 946-52. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 71. Bigot NJ, Neyaz A, Alani A, et al. Malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumour with TP53::PHF1 fusion: report of three cases suggesting an association between rare fusions and malignant phenotypes. Histopathology 2025; 87: 332-7. ArticlePubMed

- 72. Killian K, Leckey BD, Naous R, McGough RL, Surrey LF, John I. Novel MEAF6-SUZ12 fusion in ossifying fibromyxoid tumor with unusual features. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2021; 60: 631-4. ArticlePubMed

- 73. Kao YC, Sung YS, Zhang L, Chen CL, Huang SC, Antonescu CR. Expanding the molecular signature of ossifying fibromyxoid tumors with two novel gene fusions: CREBBP-BCORL1 and KDM2A-WWTR1. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2017; 56: 42-50. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 74. McEvoy MT, Blessing MM, Fisher KE, et al. A novel case of malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumor with a BCOR internal tandem duplication in a child. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2023; 70: e29972. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 75. Micci F, Panagopoulos I, Bjerkehagen B, Heim S. Consistent rearrangement of chromosomal band 6p21 with generation of fusion genes JAZF1/PHF1 and EPC1/PHF1 in endometrial stromal sarcoma. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 107-12. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 76. Dickson BC, Lum A, Swanson D, et al. Novel EPC1 gene fusions in endometrial stromal sarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2018; 57: 598-603. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 77. Graham RP, Weiss SW, Sukov WR, et al. PHF1 rearrangements in ossifying fibromyxoid tumors of soft parts: a fluorescence in situ hybridization study of 41 cases with emphasis on the malignant variant. Am J Surg Pathol 2013; 37: 1751-5. ArticlePubMed

- 78. Atanaskova Mesinkovska N, Buehler D, McClain CM, Rubin BP, Goldblum JR, Billings SD. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor: a clinicopathologic analysis of 26 subcutaneous tumors with emphasis on differential diagnosis and prognostic factors. J Cutan Pathol 2015; 42: 622-31. ArticlePubMed

- 79. Antonescu CR, Zhang L, Chang NE, et al. EWSR1-POU5F1 fusion in soft tissue myoepithelial tumors: a molecular analysis of sixty-six cases, including soft tissue, bone, and visceral lesions, showing common involvement of the EWSR1 gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2010; 49: 1114-24. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 80. Thway K, Chisholm J, Hayes A, Swansbury J, Fisher C. Pediatric low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma mimicking ossifying fibromyxoid tumor: adding to the diagnostic spectrum of soft tissue tumors with a bony shell. Hum Pathol 2015; 46: 461-6. ArticlePubMed

- 81. Reid R, de Silva MV, Paterson L, Ryan E, Fisher C. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma and hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes share a common t(7;16)(q34;p11) translocation. Am J Surg Pathol 2003; 27: 1229-36. ArticlePubMed

- 82. Guillou L, Benhattar J, Gengler C, et al. Translocation-positive low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of a series expanding the morphologic spectrum and suggesting potential relationship to sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma: a study from the French Sarcoma Group. Am J Surg Pathol 2007; 31: 1387-402. ArticlePubMed

- 83. Mohamed M, Fisher C, Thway K. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: clinical, morphologic and genetic features. Ann Diagn Pathol 2017; 28: 60-7. ArticlePubMed

- 84. Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG, Enzinger FM. Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma: a variant of fibrosarcoma simulating carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1995; 19: 979-93. ArticlePubMed

- 85. Warmke LM, Meis JM. Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma: a distinct sarcoma with aggressive features. Am J Surg Pathol 2021; 45: 317-28. ArticlePubMed

- 86. Arbajian E, Puls F, Magnusson L, et al. Recurrent EWSR1-CREB3L1 gene fusions in sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2014; 38: 801-8. ArticlePubMed

- 87. Warmke LM, Ameline B, Fritchie KJ, et al. YAP1::KMT2A-rearranged sarcomas harbor a unique methylation profile and are distinct from sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma and low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Virchows Arch 2025; 486: 457-77. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 88. Kao YC, Lee JC, Zhang L, et al. Recurrent YAP1 and KMT2A gene rearrangements in a subset of MUC4-negative sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2020; 44: 368-77. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 89. Puls F, Agaimy A, Flucke U, et al. Recurrent fusions between YAP1 and KMT2A in morphologically distinct neoplasms within the spectrum of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma and sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2020; 44: 594-606. ArticlePubMed

- 90. Martinez-Rodriguez M, Subramaniam MM, Calatayud AM, Ramos D, Navarro S, Llombart-Bosch A. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor of soft parts mimicking a schwannoma with uncommon histology: a potential diagnostic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol 2009; 36: 71-3. ArticlePubMed

- 91. Schaefer IM, Fletcher CD, Hornick JL. Loss of H3K27 trimethylation distinguishes malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol 2016; 29: 4-13. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 92. Prieto-Granada CN, Wiesner T, Messina JL, Jungbluth AA, Chi P, Antonescu CR. Loss of H3K27me3 expression is a highly sensitive marker for sporadic and radiation-induced MPNST. Am J Surg Pathol 2016; 40: 479-89. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 93. Sbaraglia M, Bellan E, Gambarotti M, et al. Primary malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumour of the bone: a clinicopathologic and molecular report of two cases. Pathologica 2020; 112: 184-90. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 94. Wang XQ, Goytain A, Dickson BC, Nielsen TO. Advances in sarcoma molecular diagnostics. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2022; 61: 332-45. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 95. Kilpatrick SE, Ward WG, Mozes M, Miettinen M, Fukunaga M, Fletcher CD. Atypical and malignant variants of ossifying fibromyxoid tumor: clinicopathologic analysis of six cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1995; 19: 1039-46. ArticlePubMed

- 96. Provenzano S, Raimondi A, Bertulli RM, et al. Response to isolated limb perfusion and chemotherapy with epirubicin plus ifosfamide in a metastatic malignant ossifying fibromyxoid tumor. Clin Sarcoma Res 2017; 7: 20.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 97. Lastra RR, Newman JG, Brooks JS, Huang JH. Ossifying fibromyxoid tumor metastatic to the thyroid: a case report and review of the literature. Ear Nose Throat J 2014; 93: 221-3. ArticlePubMedPDF

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link-

Cite this Article

Cite this Article

- Cite this Article

-

- Close

- Download Citation

- Close

- Figure

E-submission

E-submission