Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Pathol Transl Med > Forthcoming articles > Article

-

Review Article

The evolving role of TRPS1 in dermatopathology: insights from the past 4 years -

Mokhtar H. Abdelhammed1

, Woo Cheal Cho2

, Woo Cheal Cho2

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2025.11.25

Published online: January 29, 2026

1Department of Pathology and Immunology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA

2Department of Anatomical Pathology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA

- Corresponding Author: Woo Cheal Cho, MD Department of Anatomical Pathology, Section of Dermatopathology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, B3.4607, Unit 085, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030-4009, USA Tel: +1-832-785-9136, Fax: +1-713-745-0789, E-mail: WCho@mdanderson.org

© The Korean Society of Pathologists/The Korean Society for Cytopathology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 44 Views

- 5 Download

- Abstract

- INTRODUCTION

- ANTI-TRPS1 ANTIBODIES

- TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN NORMAL SKIN

- TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN CUTANEOUS NON-ADNEXAL EPITHELIAL NEOPLASMS

- TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN CUTANEOUS ADNEXAL NEOPLASMS

- TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN TUMORS WITH APOCRINE AND ECCRINE DIFFERENTIATION

- TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN TUMORS WITH FOLLICULAR DIFFERENTIATION

- TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN TUMORS WITH SEBACEOUS DIFFERENTIATION

- TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN SITE-SPECIFIC ADNEXAL TUMORS

- TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN MELANOCYTIC NEOPLASMS

- TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN CUTANEOUS MESENCHYMAL NEOPLASMS

- TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN CUTANEOUS METASTATIC CARCINOMAS

- CONCLUSION

- NOTES

- REFERENCES

Abstract

- Over the past 4 years, trichorhinophalangeal syndrome type 1 (TRPS1) has rapidly gained attention among practicing pathologists, with numerous studies emerging that both support and question its diagnostic utility. Initially regarded as a highly specific marker for tumors of mammary origin, TRPS1 is now recognized to have broader expression patterns, including in a variety of cutaneous neoplasms. This is likely due to embryologic parallels between breast tissue and skin adnexal structures, an overlap that was underappreciated in early investigations. Although TRPS1 lacks absolute specificity—even among cutaneous neoplasms—it can still offer meaningful diagnostic value when interpreted alongside conventional immunohistochemical markers and within the appropriate morphologic context. Noteworthy diagnostic applications include mammary Paget disease, primary extramammary Paget disease, rare adnexal neoplasms such as endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma and primary cutaneous NUT adnexal carcinoma, and cutaneous metastases from breast carcinoma. In this review, we present the most comprehensive and up-to-date evaluation of the utility and limitations of TRPS1 immunohistochemistry in dermatopathology. Our aim is to deepen understanding of this emerging marker and provide practical guidance on its optimal integration with established immunohistochemical panels to enhance diagnostic accuracy in routine practice.

- Trichorhinophalangeal syndrome type 1 (TRPS1) immunohistochemistry (IHC) has gained significant traction among surgical pathologists and cytopathologists in recent years, initially being regarded as a highly sensitive and specific marker for carcinomas of mammary origin [1]. However, the study by Ai et al. [1], which first highlighted its potential, had a significant limitation: the authors employed tissue microarrays for analysis instead of whole tissue sections. This approach failed to account for the heterogeneity of TRPS1 expression within the same tumor types, undermining the robustness of their findings. Furthermore, their analysis excluded most cutaneous neoplasms, focusing primarily on melanomas, casting doubt on their assertion that TRPS1 expression is “highly specific” for breast carcinomas [1].

- Subsequent studies have challenged this claim, demonstrating that TRPS1 expression extends beyond breast neoplasms. Tumors in sites with embryological similarities to breast tissue, such as skin adnexal structures, often share similar immunoprofiles (e.g., cytokeratin [CK] 7+/GATA3+). TRPS1 expression has been notably observed in various cutaneous adnexal neoplasms, including mammary Paget diseases (MPDs) [2,3], extramammary Paget diseases (EMPDs) [2-4], endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinomas (EMPSGCs) [5], and numerous other cutaneous adnexal tumors [6-11].

- In this review, we provide the most comprehensive and up-to-date examination of the utility and limitations of TRPS1 IHC in cutaneous neoplasms, encompassing not only adnexal tumors but also other epithelial and mesenchymal neoplasms of cutaneous origin. This knowledge will deepen our understanding of this emerging marker in dermatopathology and offer guidance on how to optimally integrate TRPS1 IHC with other established immunohistochemical markers to improve diagnostic accuracy in routine dermatopathology practice.

INTRODUCTION

- The successful detection of TRPS1 expression in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues hinges on the selection of an optimal antibody and immunohistochemical protocol. Among the various anti-TRPS1 antibodies and clones reported in the literature, EPR16171, a rabbit monoclonal antibody, appears to be the most widely used for IHC [3,5-8,12]. However, its application varies across laboratories, with differences in antibody dilution (e.g., 1:2,000 [3,5,6,12] vs. 1:6,000 [7,8]), incubation times, antigen retrieval methods, and staining platforms.

- The second most frequently employed anti-TRPS1 antibody is PA5-84587, a rabbit polyclonal antibody, used at diverse dilutions such as 1:100 [1], 1:250 [9], and 1:1,000 [4]. Another reported clone is ZR382, a rabbit monoclonal antibody used at a 1:200 dilution [13,14].

- In our own experience, both monoclonal and polyclonal anti-TRPS1 antibodies have been evaluated. Notably, the monoclonal antibody EPR16171 reliably demonstrates TRPS1 expression in FFPE skin specimens. Internal controls, such as eccrine glands, consistently show strong (3+) expression intensity, supporting the reproducibility and robustness of this clone under our testing conditions.

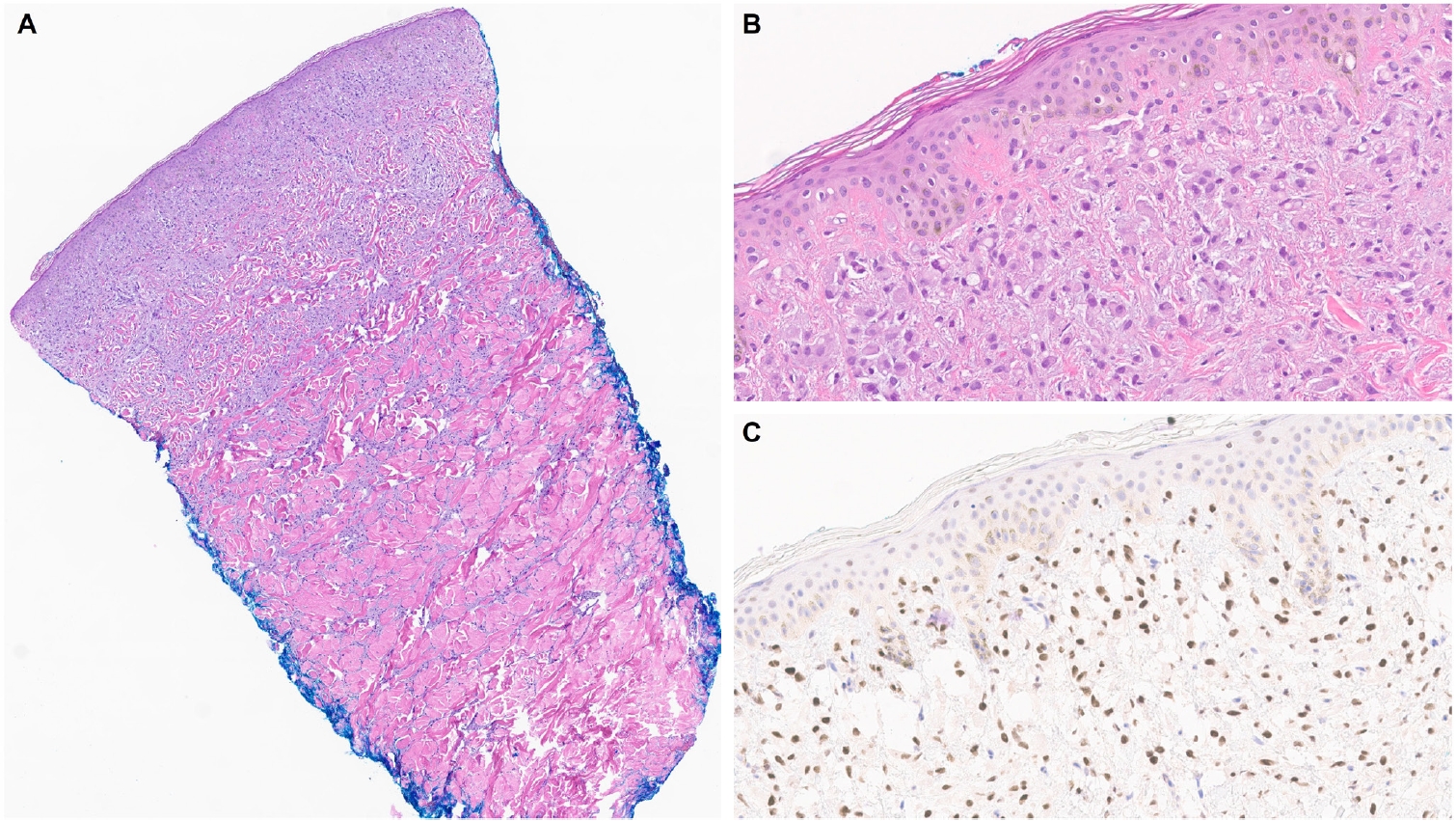

ANTI-TRPS1 ANTIBODIES

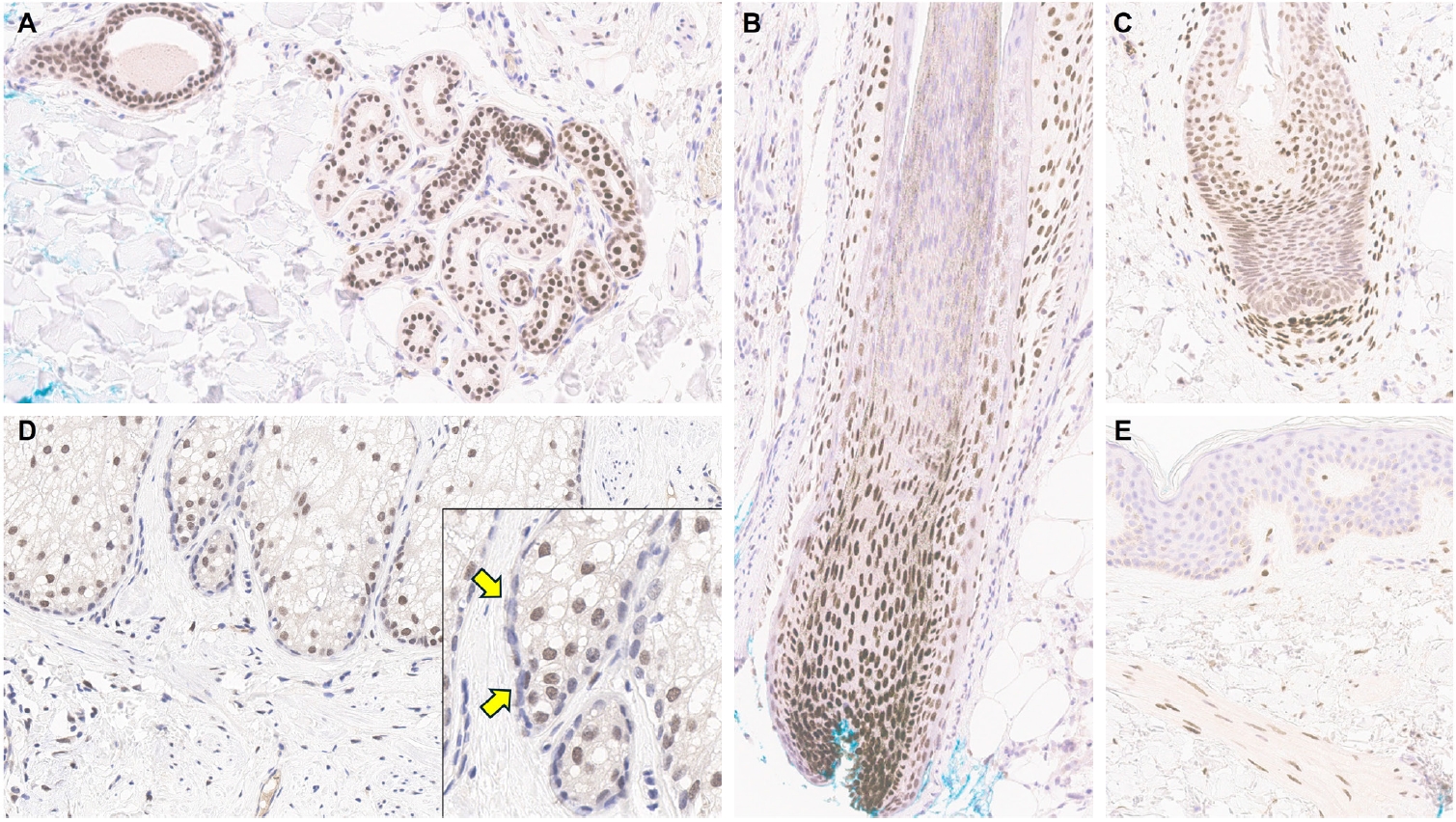

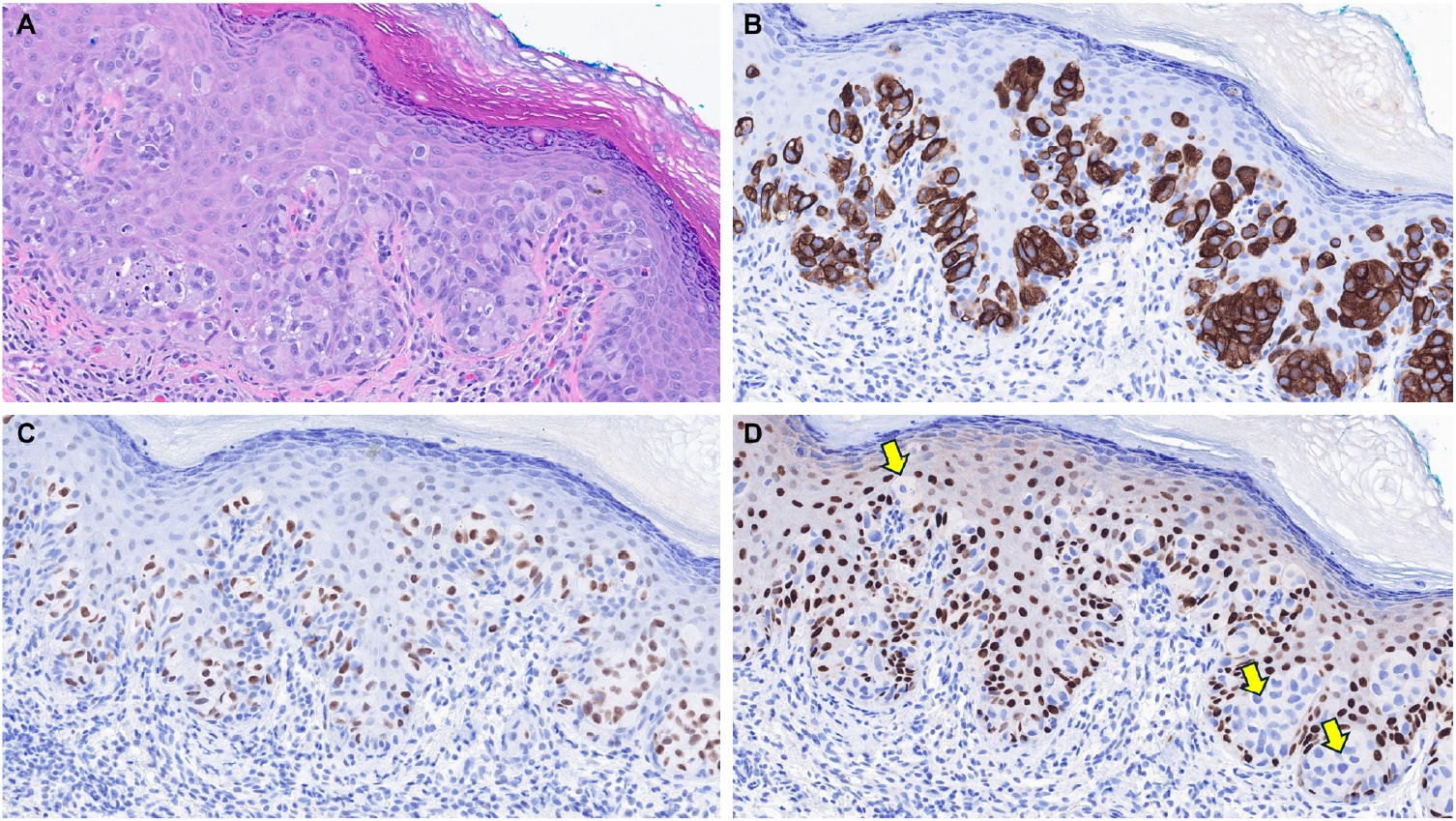

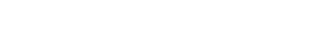

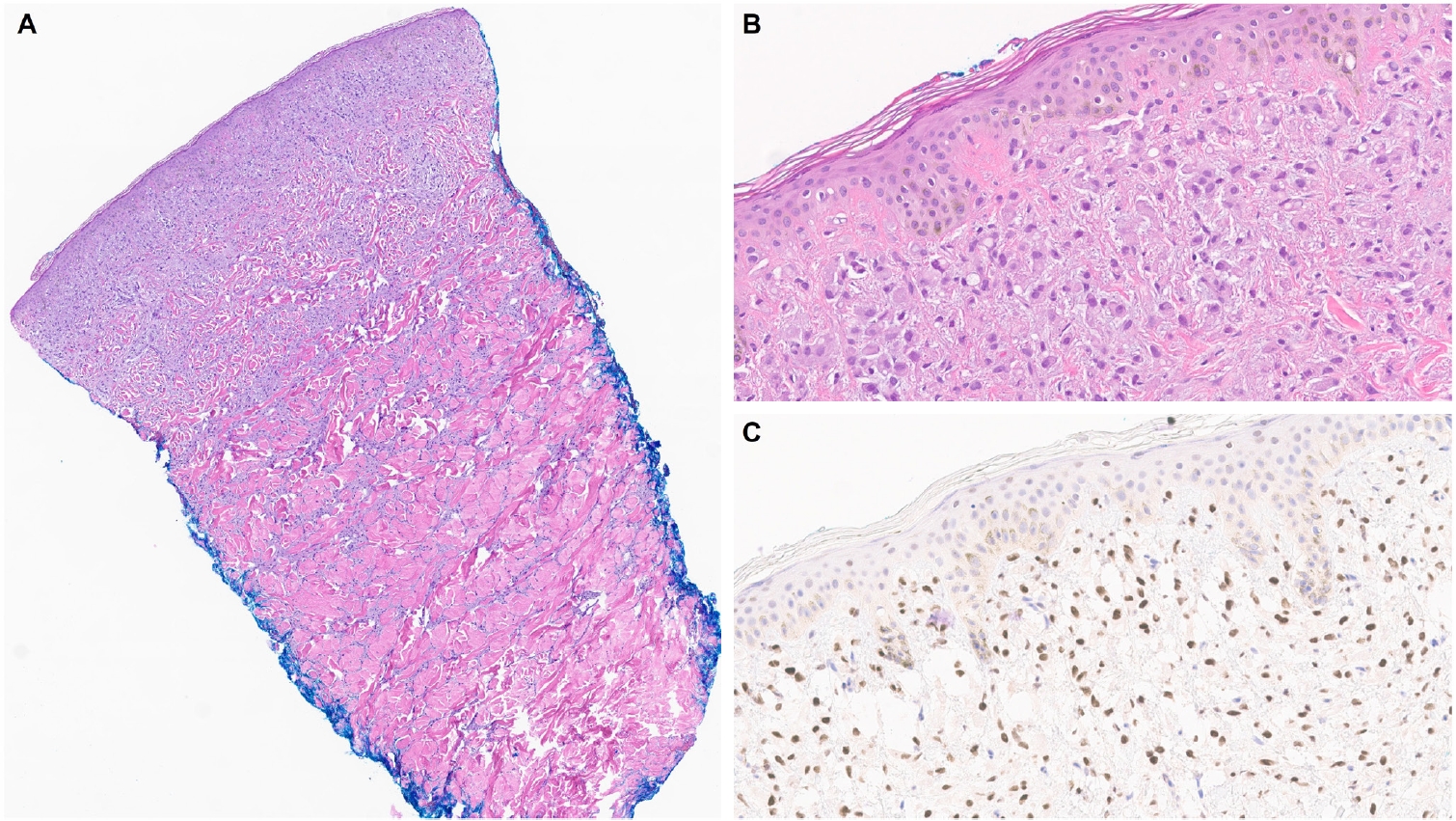

- Understanding TRPS1 expression in the innate cellular and structural components of normal skin is crucial for identifying the types of cutaneous neoplasms that may express this marker. Neoplastic cells often retain the immunoprofile of their normal cellular counterparts as they proliferate and transform. In normal skin, TRPS1 immunoreactivity is prominently observed in various adnexal structures (Table 1), with the strongest expression (3+) found in eccrine glands (Fig. 1A), acrosyringia, matrical cells (Fig. 1B), and mesenchymal cells of the dermal papillae (Fig. 1C) [2,6]. These structures serve as ideal internal controls due to their consistent, robust TRPS1 expression. Sebocytes in sebaceous glands typically show weak-to-moderate (1+ to 2+) TRPS1 immunoreactivity, while the germinative cells of these glands are devoid of expression (Fig. 1D) [2,6]. Hair follicles exhibit variable TRPS1 expression in the outer and inner root sheaths and matrical cells, generally ranging from weak to strong intensity (1+ to 3+) (Fig. 1B) [2,6]. Arrector pili muscles also show natural TRPS1 immunoreactivity with weak-to-moderate intensity (1+ to 2+) (Fig. 1E). Notably, innate apocrine glands in normal skin do not express TRPS1 [2,6]. In contrast, anogenital mammary-like glands exhibit strong (3+) TRPS1 immunoreactivity [9].

- Regarding non-adnexal epithelial components, epidermal keratinocytes in the stratum spinosum may display weak-to-moderate (1+ to 2+) TRPS1 expression [2,6]. Although this TRPS1 immunoreactivity in innate epidermal keratinocytes was initially thought to be restricted to actinically damaged skin, it was later found that the epidermis from sun-protected sites can also occasionally express TRPS1 in weak-to-moderate (1+ to 2+) intensity [2,6]. The exact frequency of TRPS1 immunoreactivity in normal epidermal keratinocytes, as well as the comparison between sun-damaged and sun-protected skin, remains largely unknown at this point. Interestingly, while weak-to-moderate TRPS1 expression may be present in the normal epidermis, basal keratinocytes, unlike those in the stratum spinosum, naturally lack TRPS1 expression [2,6].

TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN NORMAL SKIN

- Most studies investigating TRPS1 expression in cutaneous non-adnexal epithelial neoplasms have focused on malignant tumors such as squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), and Merkel cell carcinomas (MCCs) (Table 1). A recent comprehensive study analyzing TRPS1 immunoreactivity across 200 cases of various cutaneous neoplasms found that nearly all SCCs (94%) demonstrated moderate to strong TRPS1 expression, with a median H-score of 200 [6]. Interestingly, the intensity of TRPS1 expression often decreases as SCC cells invade deeper into the dermis, whereas stronger expression tends to be retained in cells near the epidermis or within in situ components. This observation is supported by an earlier study showing diffuse and strong TRPS1 expression in 92% of SCC in situ (SCCIS) cases [2].

- In contrast, the same study by Liu et al. [6] reported that the majority of BCCs (90%) either lacked TRPS1 expression entirely or showed only focal immunoreactivity, with a median H-score of 5. Given that BCCs are thought to originate from the basal layer of the interfollicular epidermis [21], the minimal TRPS1 expression may reflect the absence of TRPS1 expression in native basal keratinocytes. The difference in TRPS1 expression between SCCs and BCCs was statistically significant (p < .001) [6], highlighting its potential diagnostic utility in distinguishing between these entities. The authors further investigated whether squamous differentiation in BCCs might confound TRPS1-based discrimination. Even in BCCs with squamous differentiation, TRPS1 expression remained significantly more frequent in SCCs (p < .001) [6]. However, while these findings are statistically significant, clinical interpretation should be approached with caution, as exceptions do occur. For example, diffuse TRPS1 expression may occasionally be seen in BCCs with hamartomatous or infundibulocytic features and extensive squamous differentiation [6]. Conversely, TRPS1 expression may be nearly absent in rare cases of SCC [6,9].

- Therefore, in diagnostically challenging scenarios, such as distinguishing BCCs with extensive squamous differentiation from SCCs with basaloid features, a comprehensive morphologic evaluation supplemented by an immunohistochemical panel, including TRPS1, epithelial membrane antigen, and BerEP4, may provide greater diagnostic accuracy. However, the utility of this proposed IHC panel in such cases warrants confirmation in larger, future studies.

- MCCs consistently lack TRPS1 immunoreactivity, as demonstrated in prior studies [5,6]. This distinct immunophenotypic profile may be diagnostically useful in differentiating MCCs from EMPSGCs, a primary cutaneous adnexal carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation, which will be discussed in more detail below.

TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN CUTANEOUS NON-ADNEXAL EPITHELIAL NEOPLASMS

- Various benign and malignant cutaneous adnexal neoplasms have been shown to express TRPS1 with varying intensity and proportion [2-11,13,15,16,22], indicating that this marker is not specific to tumors of mammary origin (Table 1). However, TRPS1 generally lacks significant discriminatory power among most cutaneous adnexal neoplasms. Nonetheless, in certain diagnostic contexts, when used in combination with other immunohistochemical markers, TRPS1 may offer valuable diagnostic utility (Table 1).

TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN CUTANEOUS ADNEXAL NEOPLASMS

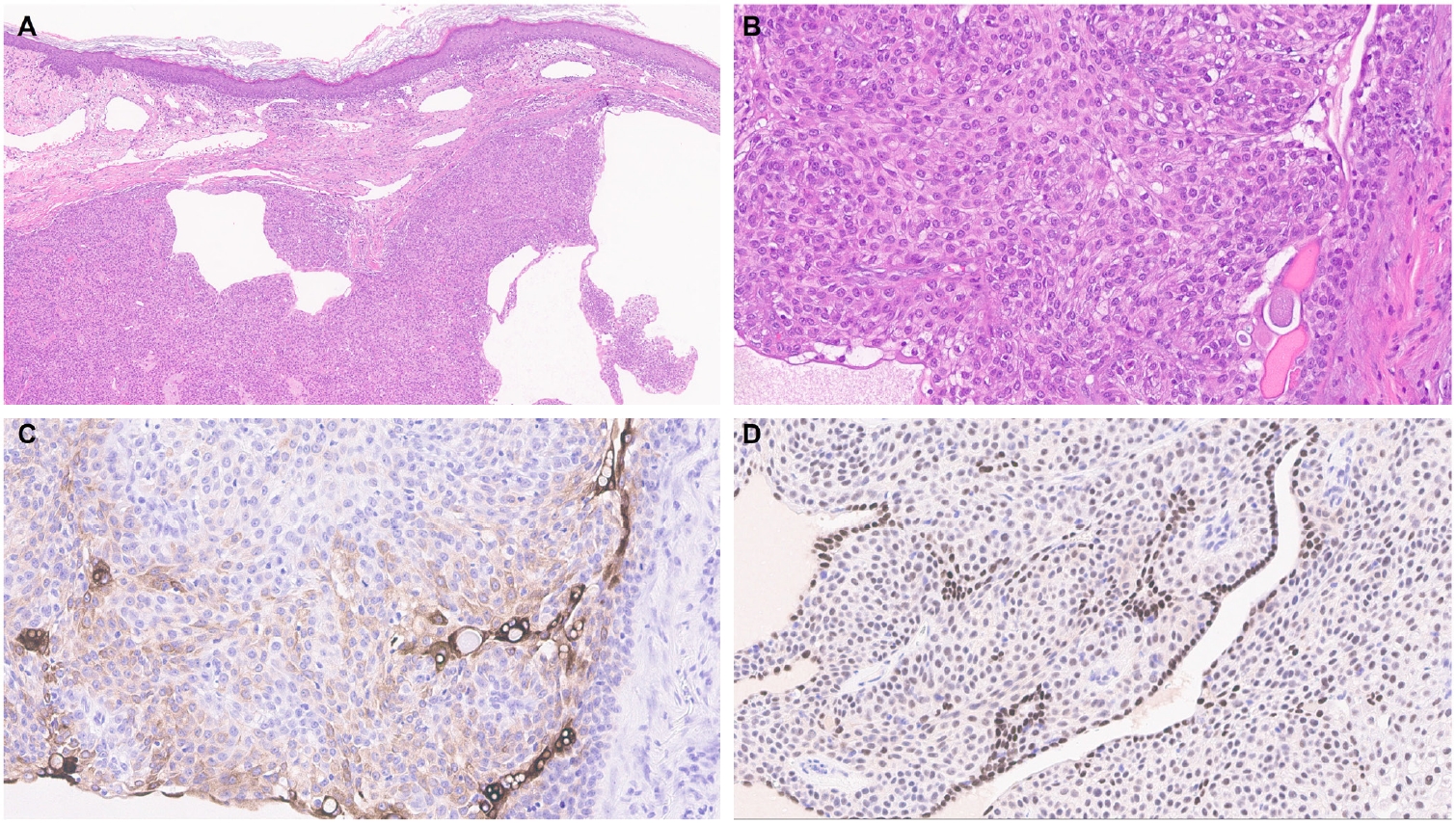

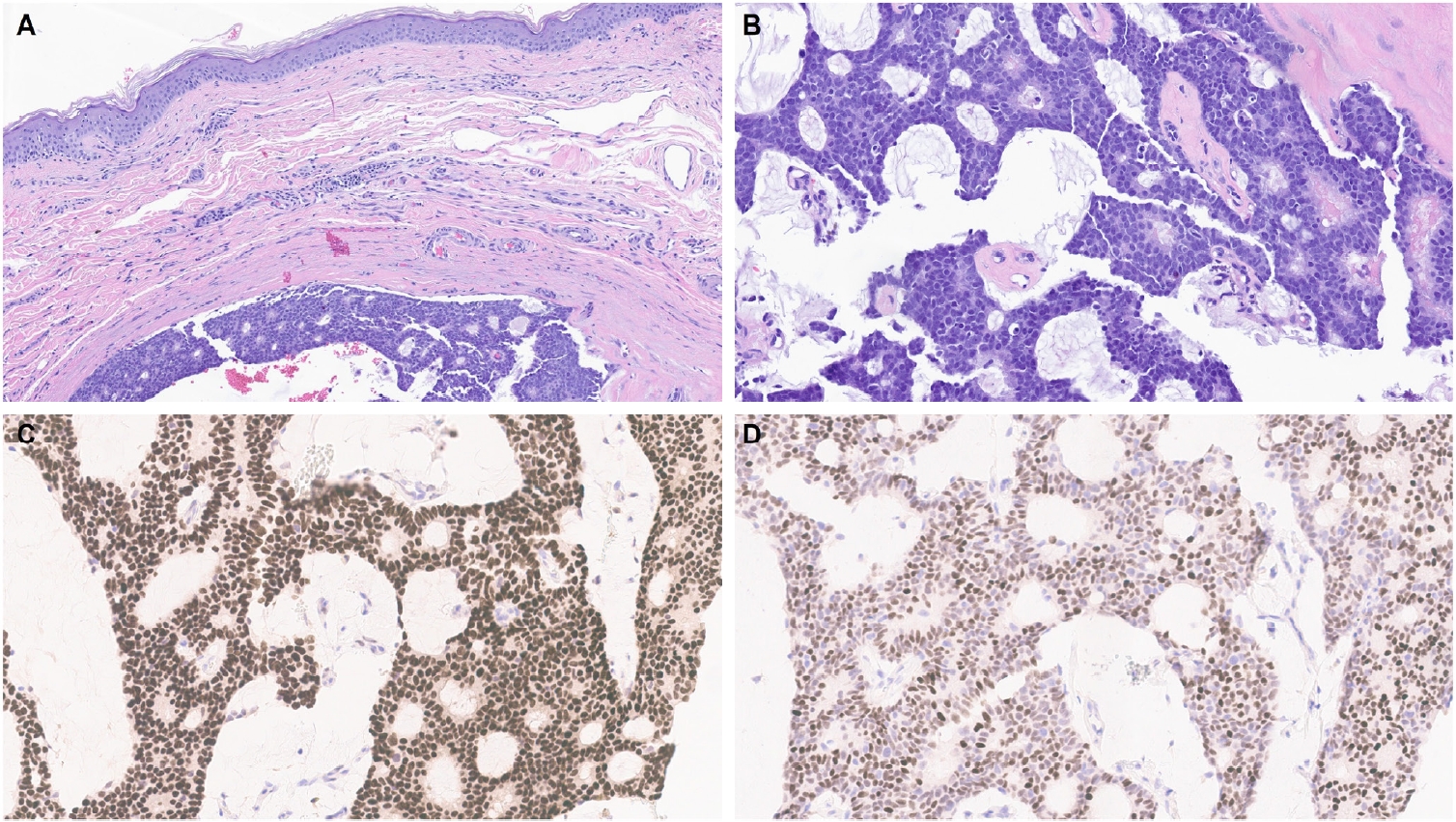

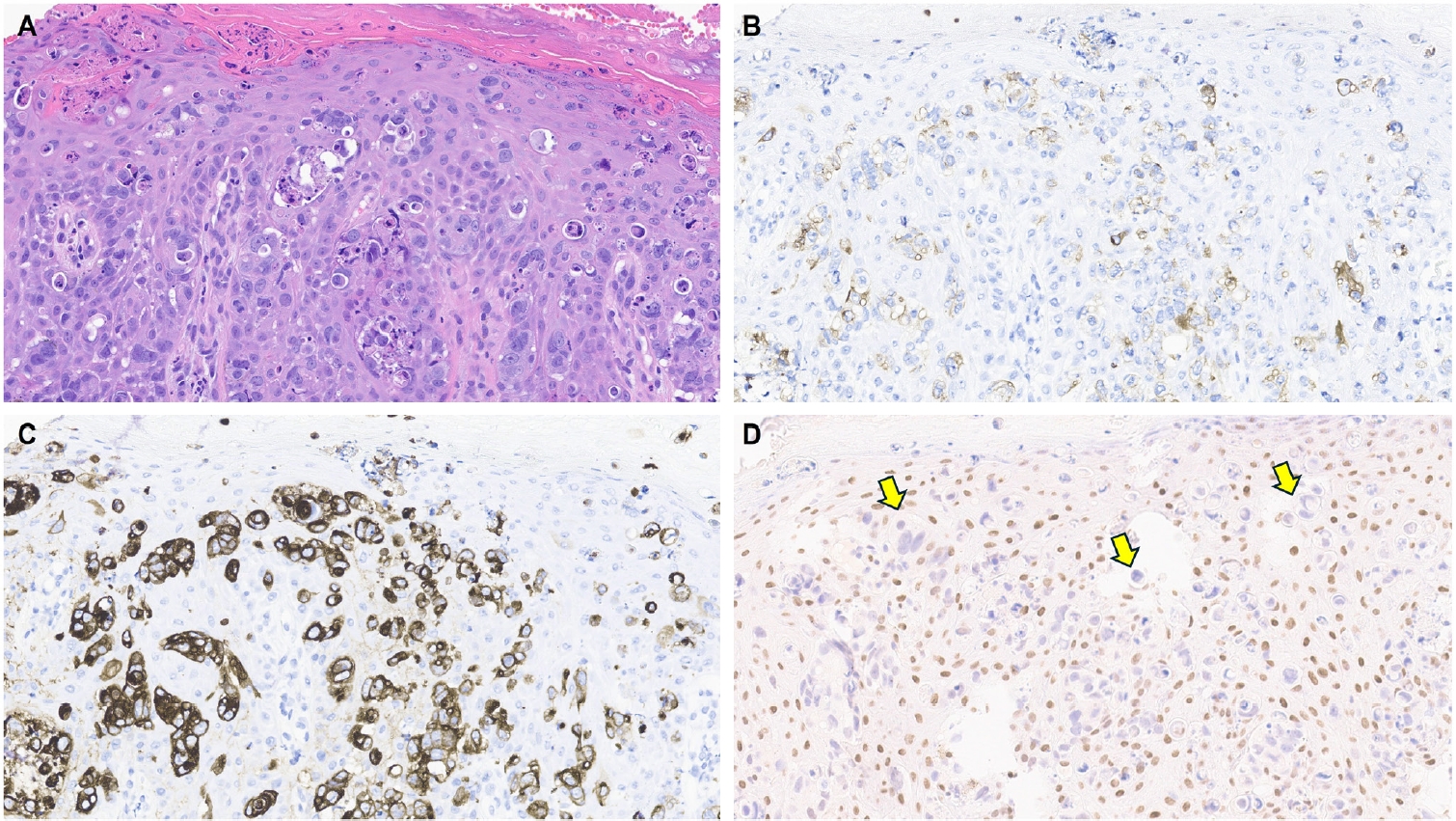

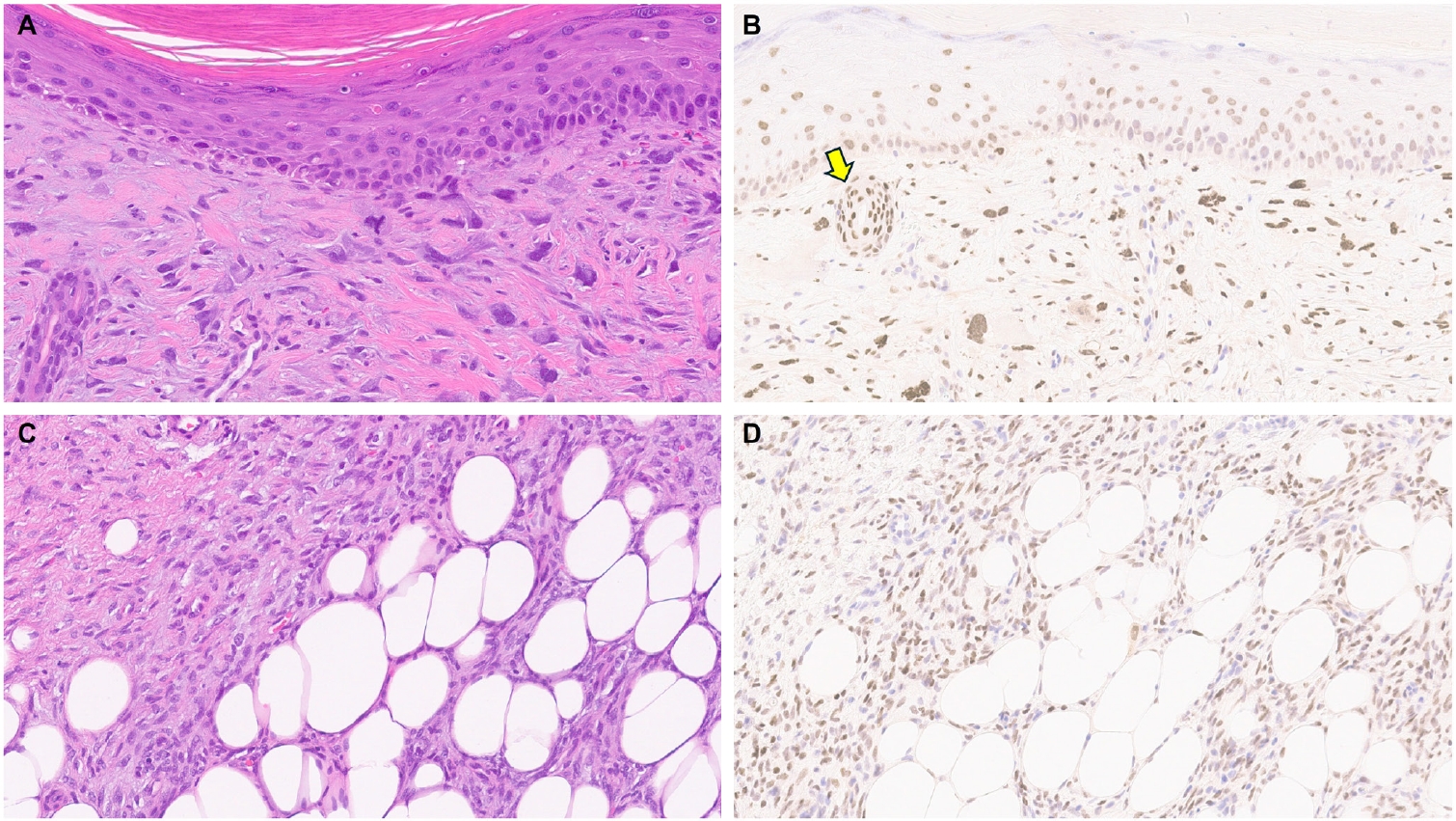

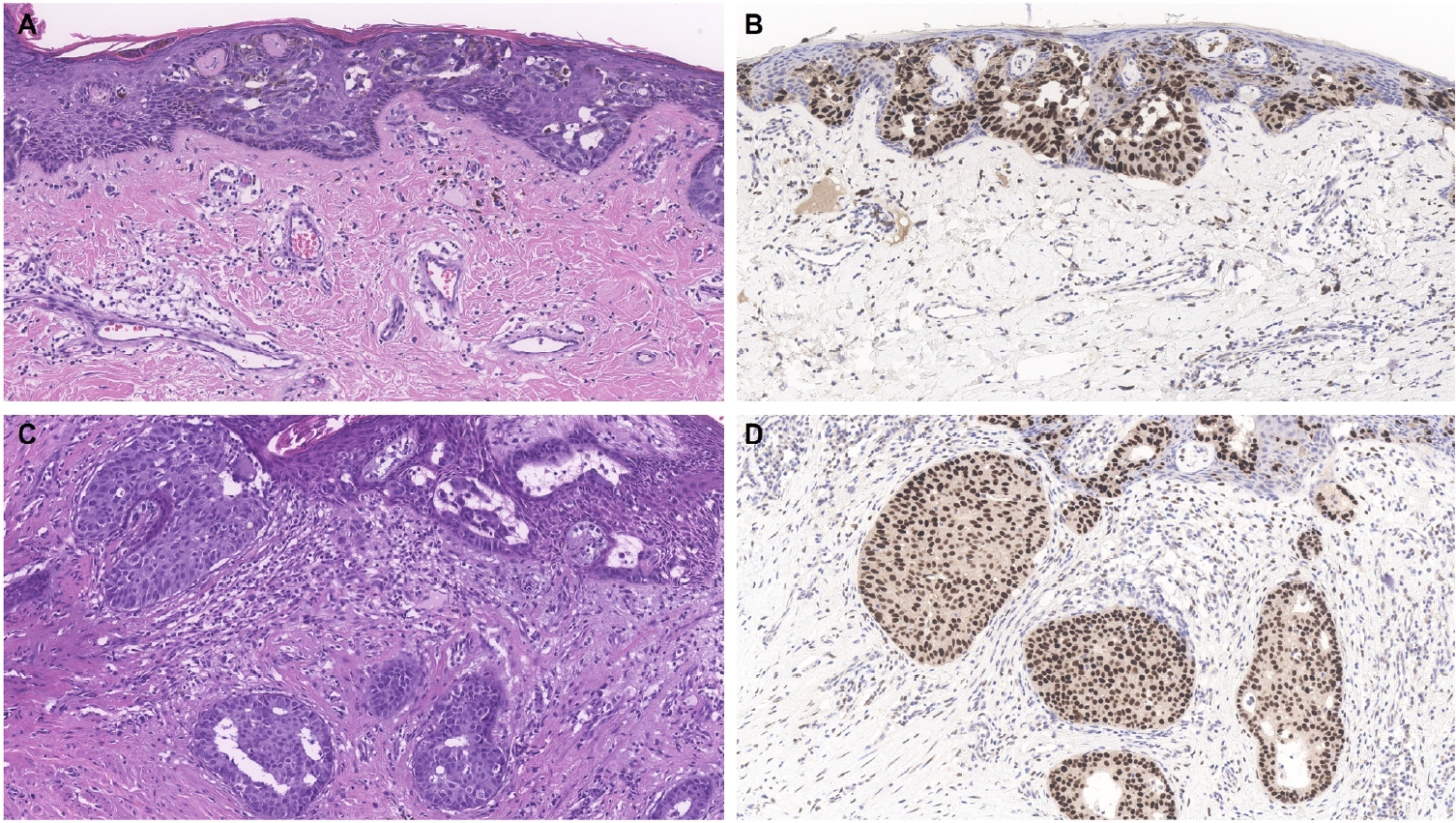

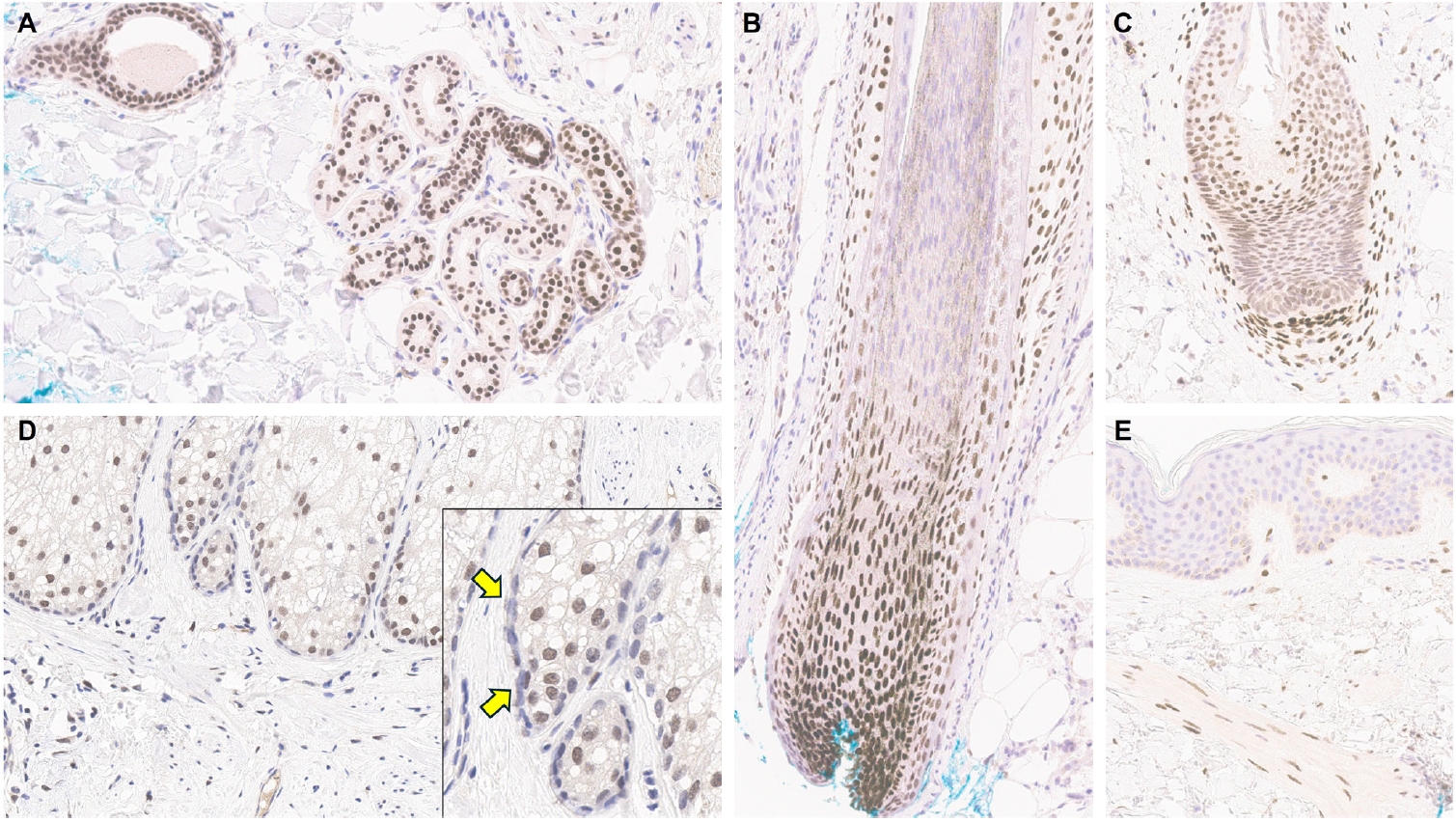

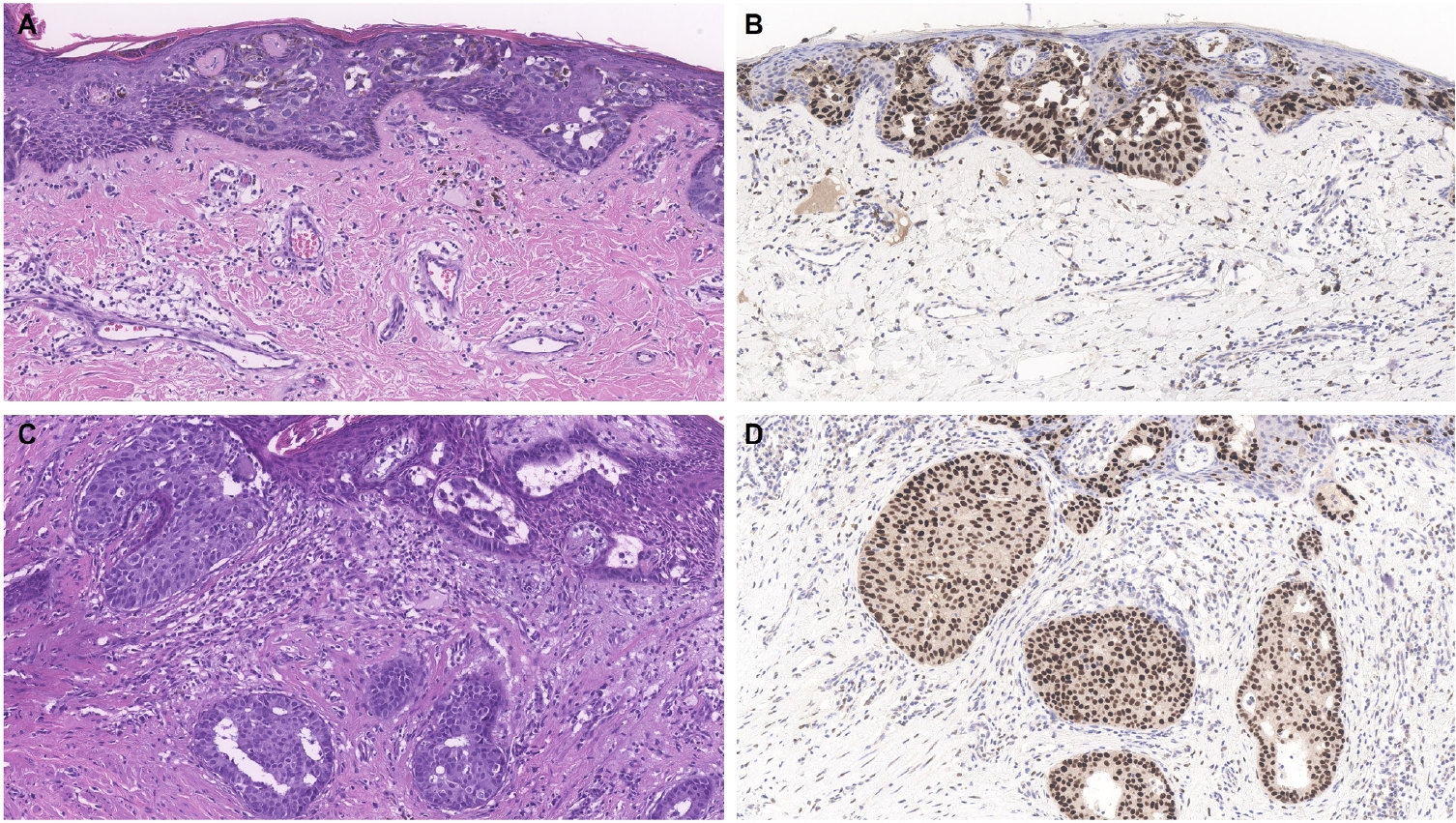

- Although not all tumor types that belong to this category of cutaneous adnexal neoplasms have been thoroughly investigated, published studies indicate that the majority, including poromas, hidradenomas (Fig. 2), spiradenomas, cylindromas, syringomas, mixed tumors, syringocystadenomas papilliferum, porocarcinomas, hidradenocarcinomas, digital papillary adenocarcinomas, squamoid eccrine ductal carcinomas, EMPSGCs, and primary cutaneous NUT adnexal carcinomas, express TRPS1 at least focally [5-7,9,10,15,16]. When present, TRPS1 expression in these tumors is typically weak-to-moderate (1+ to 2+), with the notable exception of EMPSGCs and primary cutaneous NUT adnexal carcinomas, which consistently demonstrate strong (3+) expression intensity [5,15,16], akin to that seen in eccrine glands, acrosyringia, or the mesenchymal cells of the dermal papillae. This consistent strong expression highlights the diagnostic utility of TRPS1 in identifying EMPSGCs and primary cutaneous NUT adnexal carcinomas.

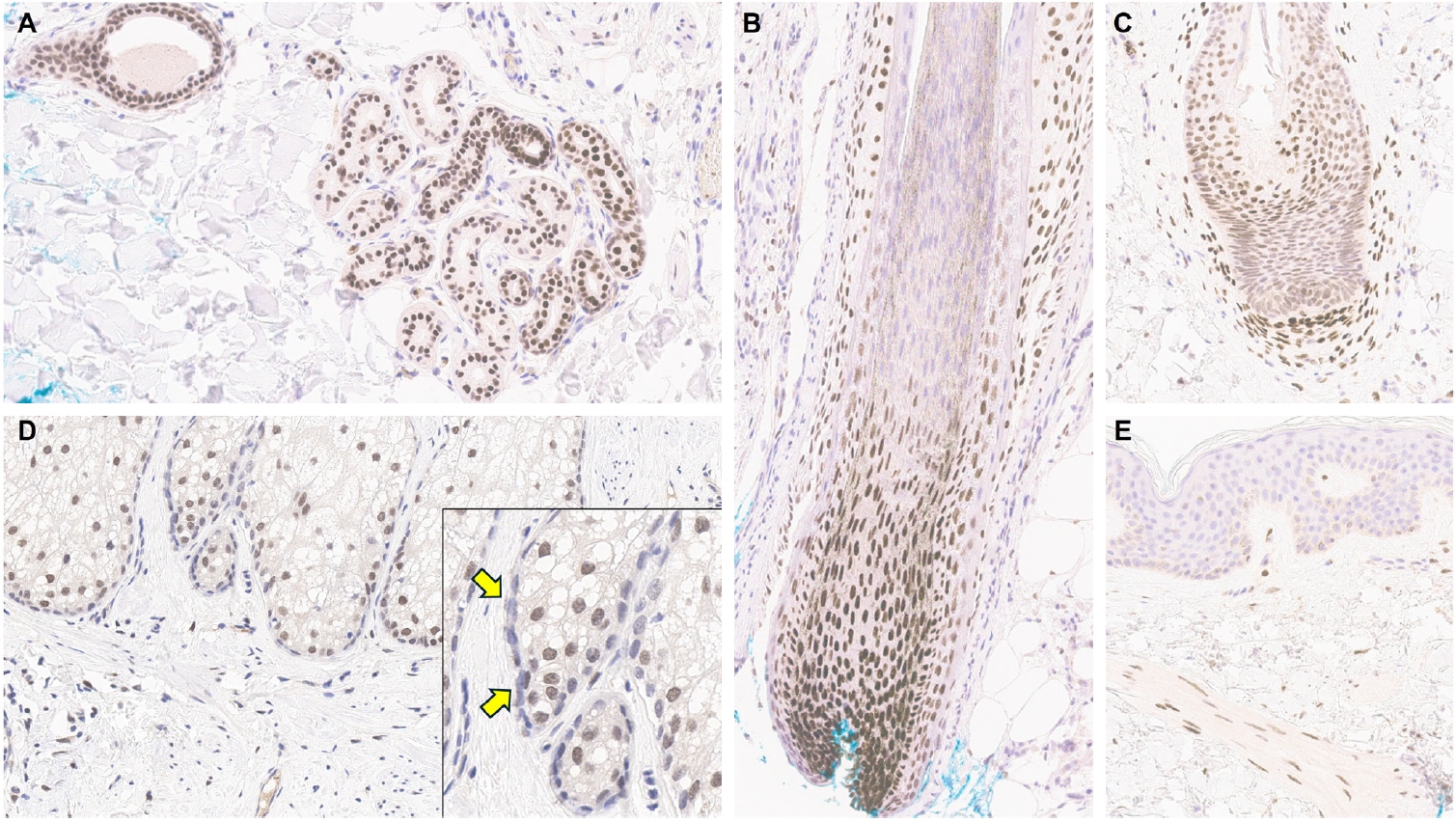

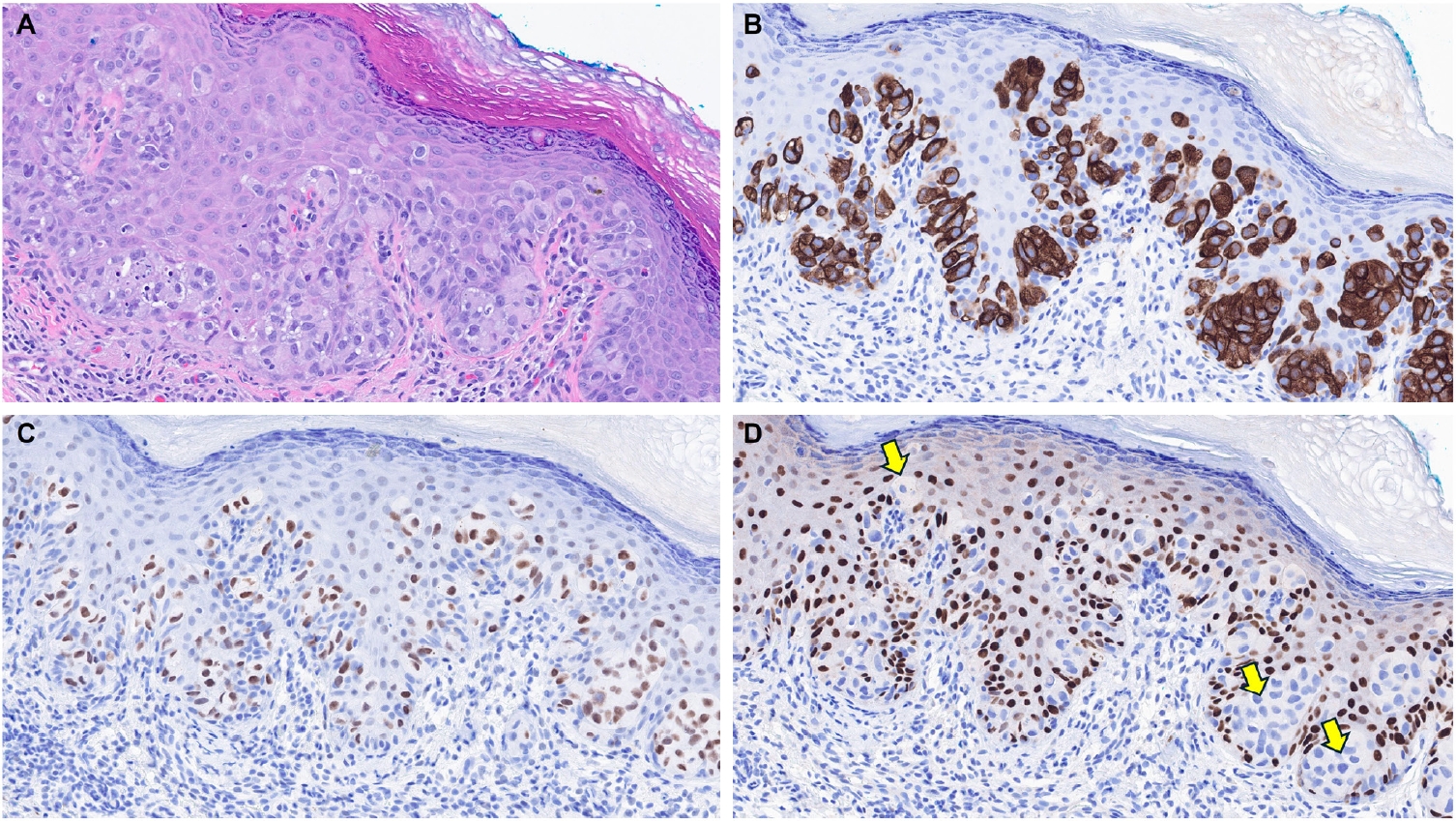

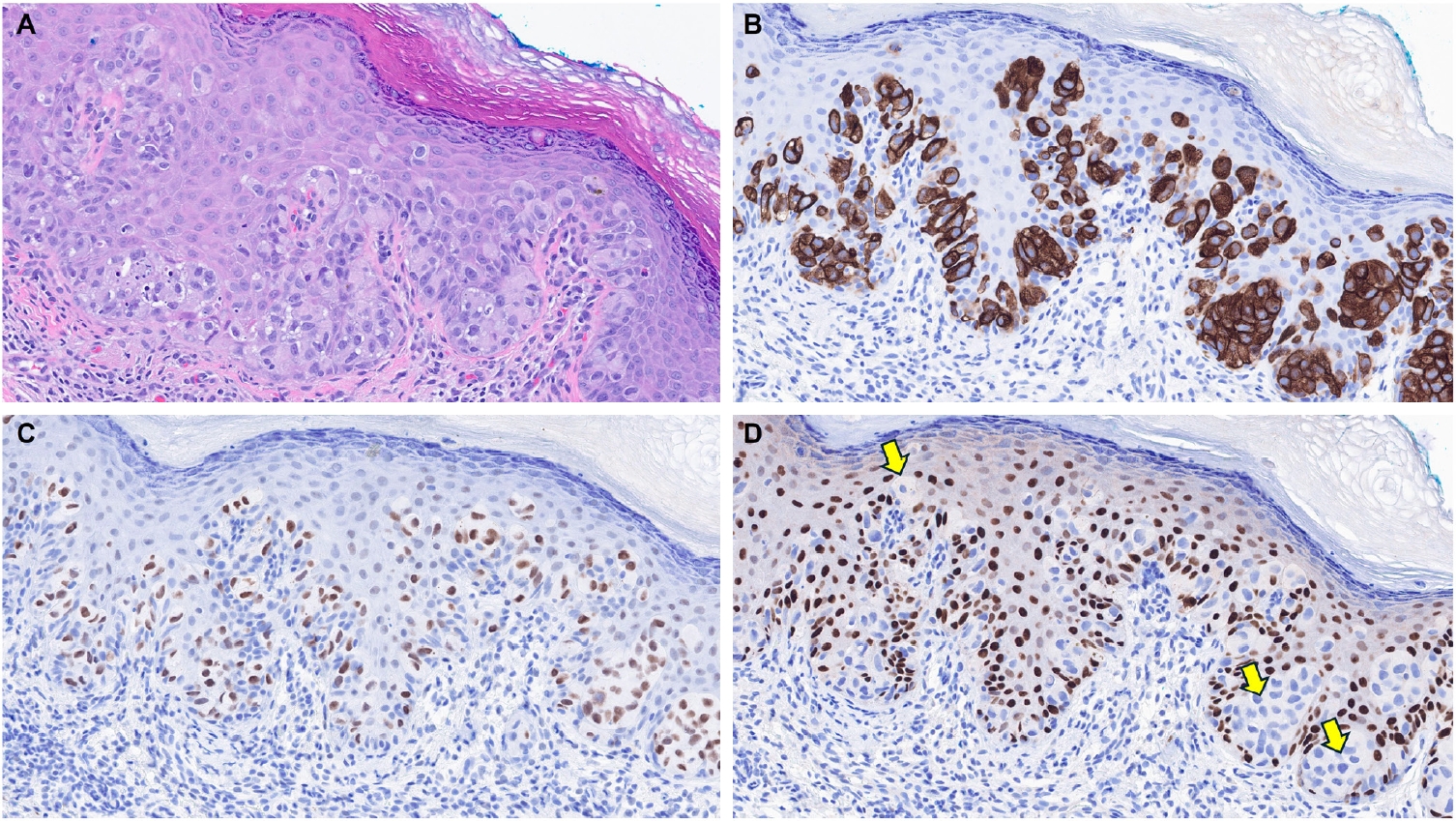

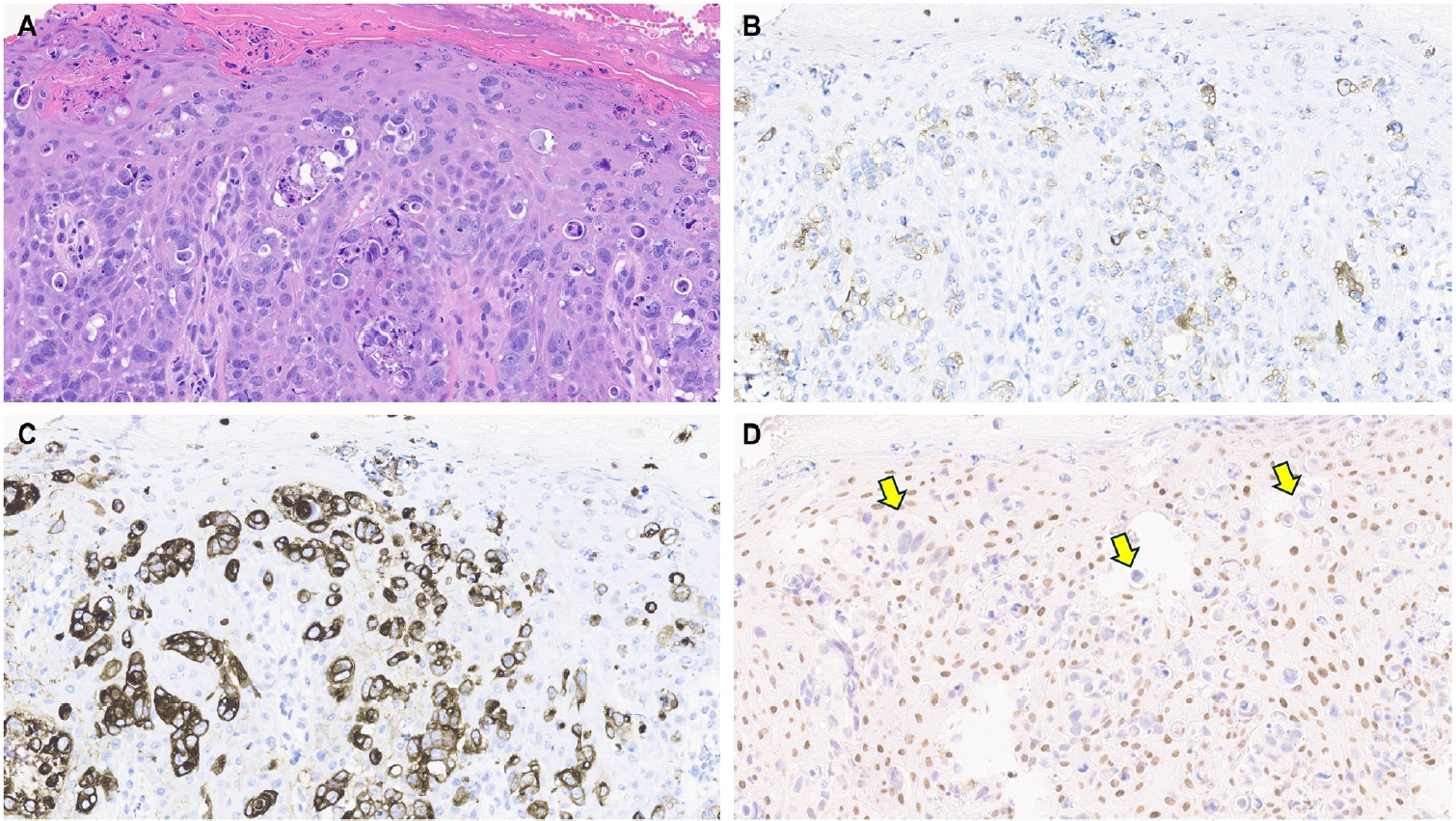

- EMPSGCs are uncommon adnexal carcinomas of sweat gland origin with neuroendocrine differentiation and are often regarded as the cutaneous analogue of solid papillary carcinoma of the breast [23,24]. Histopathologically, EMPSGCs present as nodular proliferations of basaloid cells with varied architectural patterns and frequently contain intracellular and extracellular mucin, which can mimic BCCs, especially in superficial or shallow biopsies. Immunophenotypically, their expression of neuroendocrine markers such as insulinoma-associated protein 1 (INSM1), synaptophysin, and chromogranin may also lead to confusion with MCCs, another skin malignancy with neuroendocrine differentiation, albeit more common than EMPSGCs. A recent study evaluating TRPS1 expression in EMPSGCs, BCCs, and MCCs found that all EMPSGCs demonstrated diffuse, strong TRPS1 positivity, while most BCCs and all MCCs lacked TRPS1 immunoreactivity [5]. These findings support the role of TRPS1, particularly in combination with neuroendocrine markers such as INSM1, as a valuable immunohistochemical tool for differentiating EMPSGCs (Fig. 3) from their morphologic mimics, including BCCs and MCCs. Among neuroendocrine markers, INSM1 (Fig. 3D) is especially useful in this context due to its superior sensitivity compared to others like SOX11, synaptophysin, and chromogranin [25-27].

- Primary cutaneous NUT adnexal carcinomas are a rare and recently characterized entity defined by recurrent NUTM1 or NUTM2B gene fusions [15,16,22,28]. These tumors typically exhibit a basaloid morphology, often resembling BCCs or other basaloid adnexal carcinomas such as porocarcinomas. Recent studies have shown that primary cutaneous NUT adnexal carcinomas consistently express TRPS1, SOX10, and NUT [15,16,28], suggesting that this unique immunoprofile can aid in distinguishing them from morphologically similar tumors such as porocarcinomas and BCCs. While porocarcinomas may express NUT in cases harboring a YAP1::NUTM1 fusion [29,30], they typically lack SOX10 expression [31], and TRPS1 expression in poroid neoplasms is generally not diffusely or strongly positive [6,7]. BCCs are typically negative for TRPS1, SOX10, and NUT, further supporting the diagnostic utility of this panel of IHC.

- Among the primary cutaneous adnexal carcinomas studied to date, microcystic adnexal carcinomas were found to lack TRPS1 expression in one study [7]. Consistent with the observation that normal apocrine glands are also TRPS1-negative, primary cutaneous apocrine carcinomas were initially believed to be devoid of TRPS1 expression [17]. However, a recent case report described a primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma harboring an RARA::NPEPPS fusion that showed diffuse TRPS1 positivity [11]. This finding underscores the need for additional studies with larger cohorts to clarify the true frequency and diagnostic relevance of TRPS1 expression in this rare tumor type.

TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN TUMORS WITH APOCRINE AND ECCRINE DIFFERENTIATION

- Since hair follicles inherently express TRPS1, its presence in cutaneous adnexal neoplasms of hair follicle origin or those with follicular differentiation is expected rather than incidental. Several studies have documented TRPS1 expression, at least focally and with varying intensities, in tumors such as trichoepitheliomas, trichoblastomas, trichilemmomas, trichofolliculomas, pilar sheath acanthomas, proliferating pilar tumors, pilomatricomas, malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors, trichilemmal carcinomas, and trichoblastic carcinomas [6,8,9].

- While the diagnostic value of TRPS1 in these tumors remains somewhat limited, recent work suggests it may aid in differentiating trichoepitheliomas and trichoblastomas from BCCs, their morphologic mimics [8]. Mesenchymal cells in the dermal papillae typically exhibit strong (3+) TRPS1 expression, and this pattern is also seen in the papillary mesenchymal bodies of trichoepitheliomas and trichoblastomas. In contrast, BCCs, though they may show weak TRPS1 expression in peritumoral stromal cells, lack papillary mesenchymal bodies. While further systematic validation is needed, TRPS1 could offer additional diagnostic and discriminative value for dermatopathologists when used alongside other established markers, such as CK20 (for innate Merkel cells) and PHLDA1 (a follicular stem cell marker), especially in challenging cases (e.g., small biopsy samples) [32].

TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN TUMORS WITH FOLLICULAR DIFFERENTIATION

- Sebaceous adenomas, sebaceomas, and sebaceous carcinomas typically show at least focal expression of TRPS1, with weak-to-moderate (1+ to 2+) intensities, reflecting the expression pattern seen in their cell of origin, sebocytes [6,9]. Due to the lack of specificity within this tumor category, TRPS1 offers limited diagnostic utility in distinguishing sebaceous adenomas from malignant counterparts like sebaceous carcinomas.

TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN TUMORS WITH SEBACEOUS DIFFERENTIATION

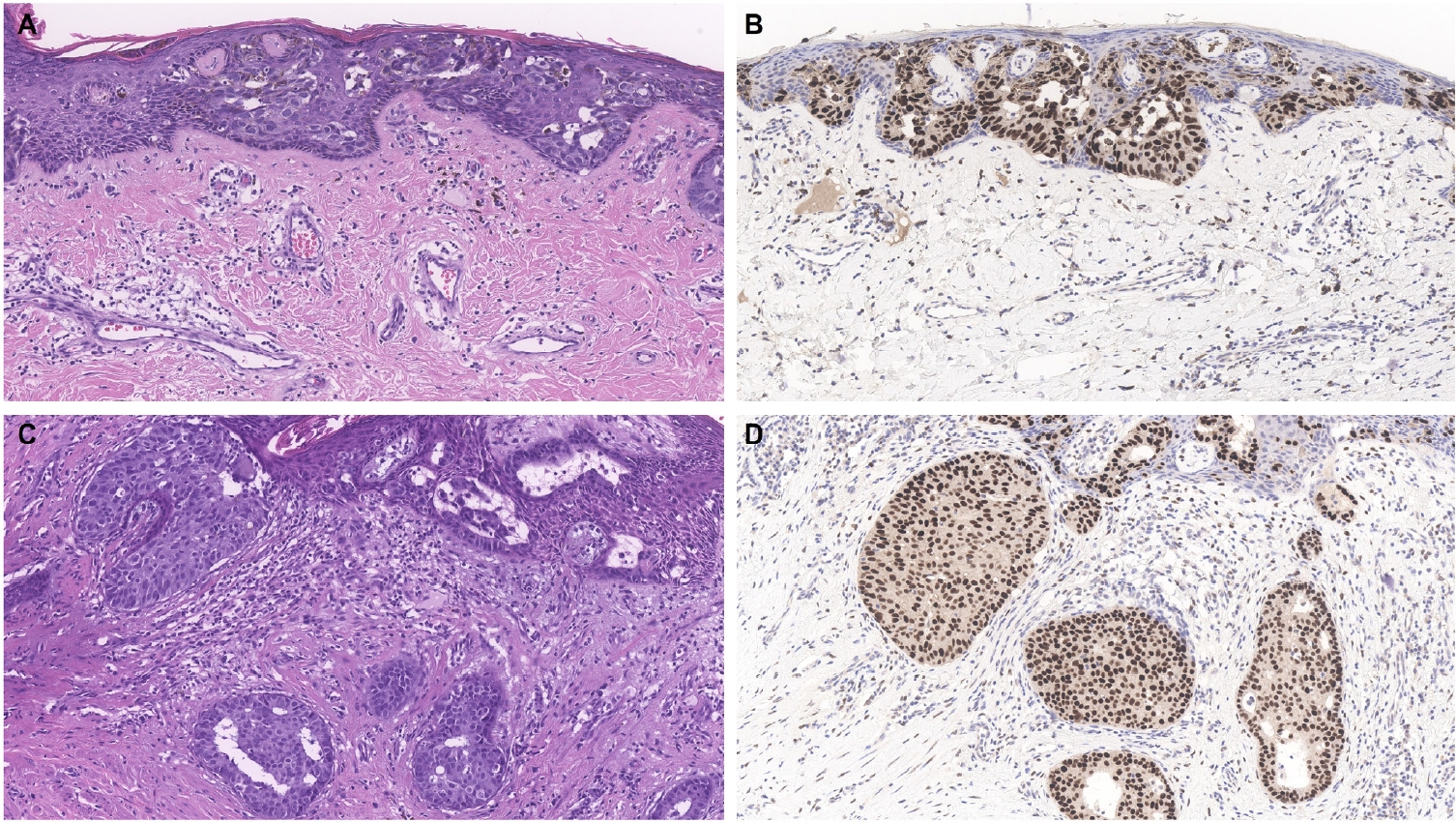

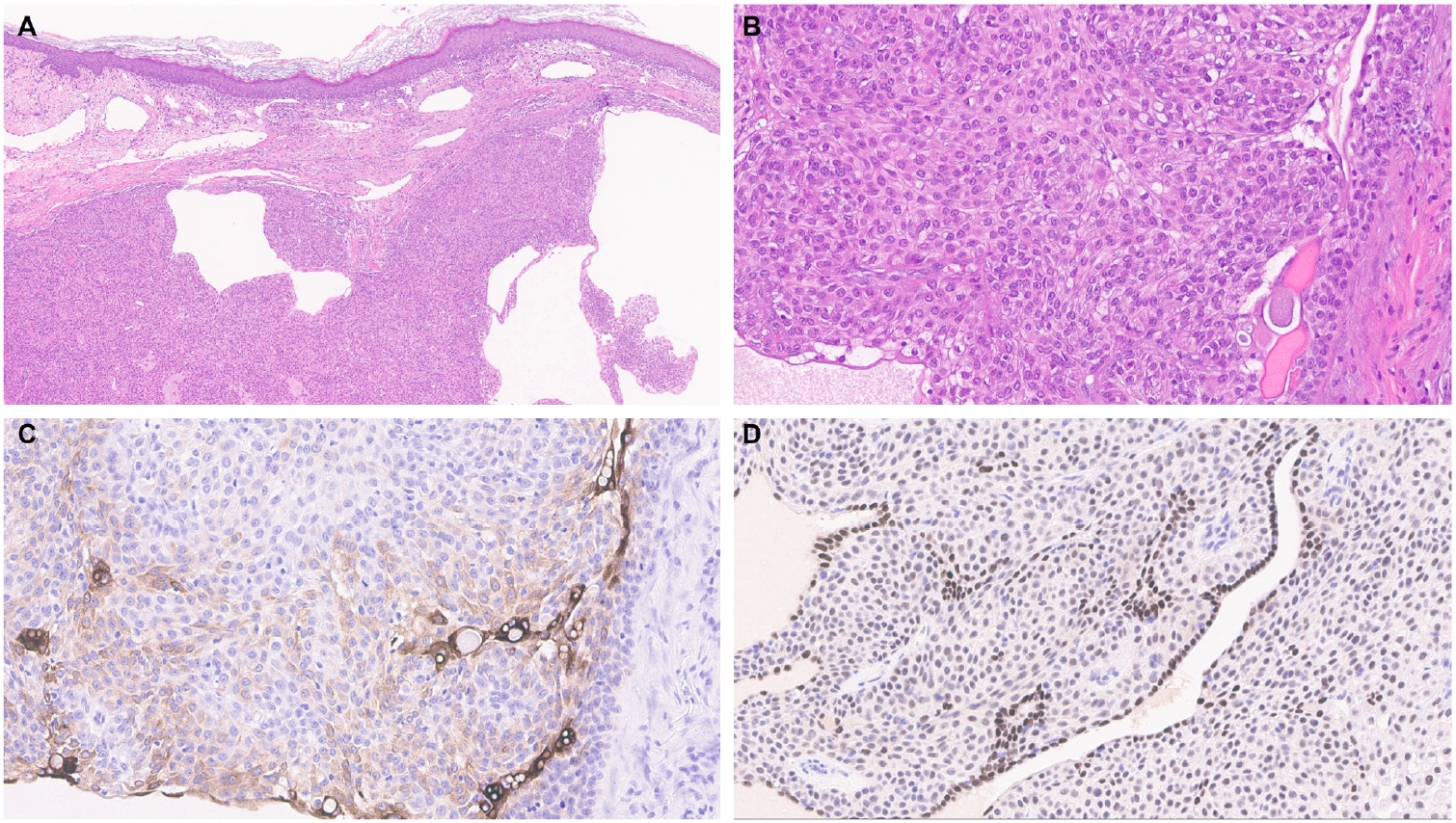

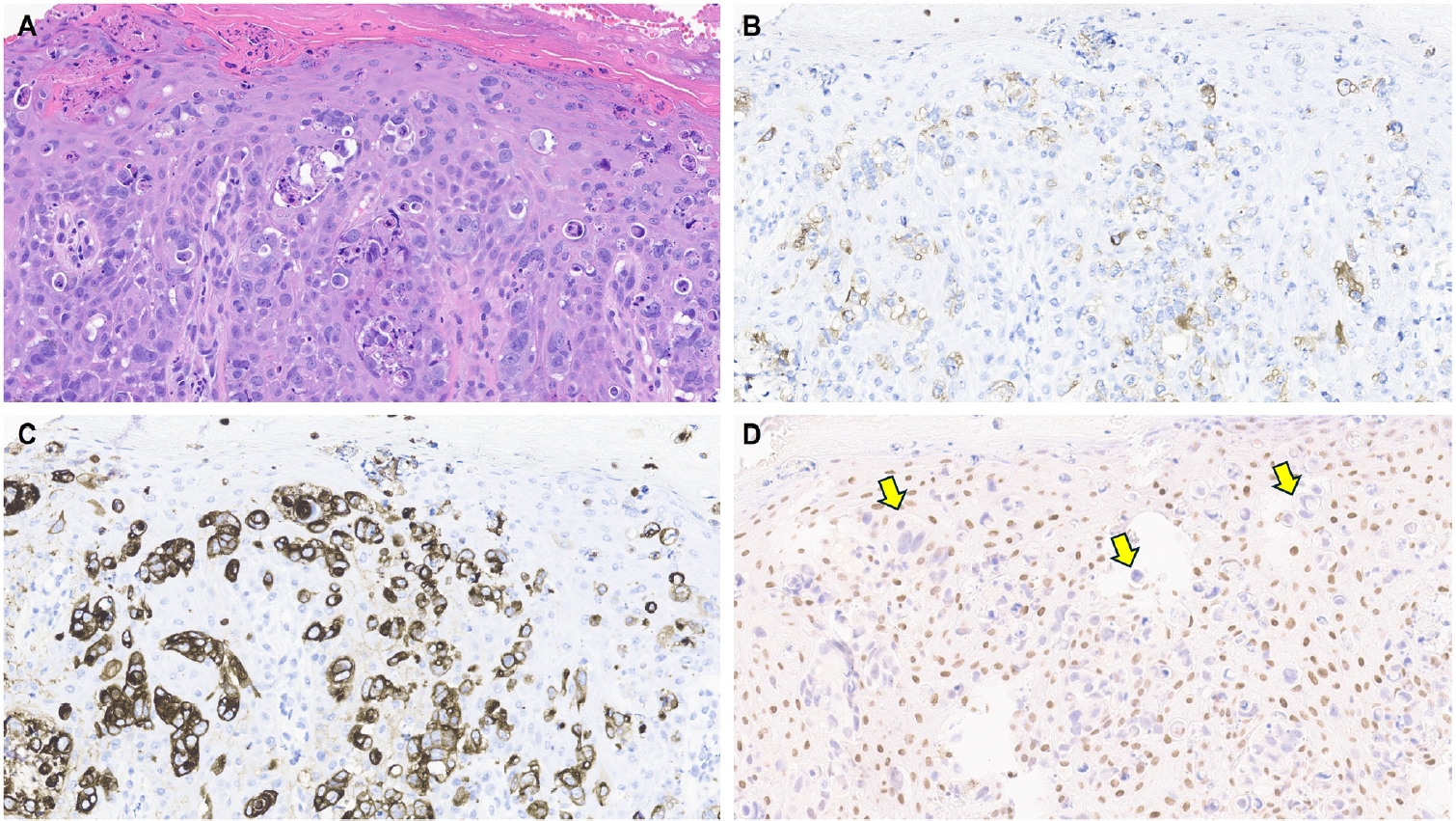

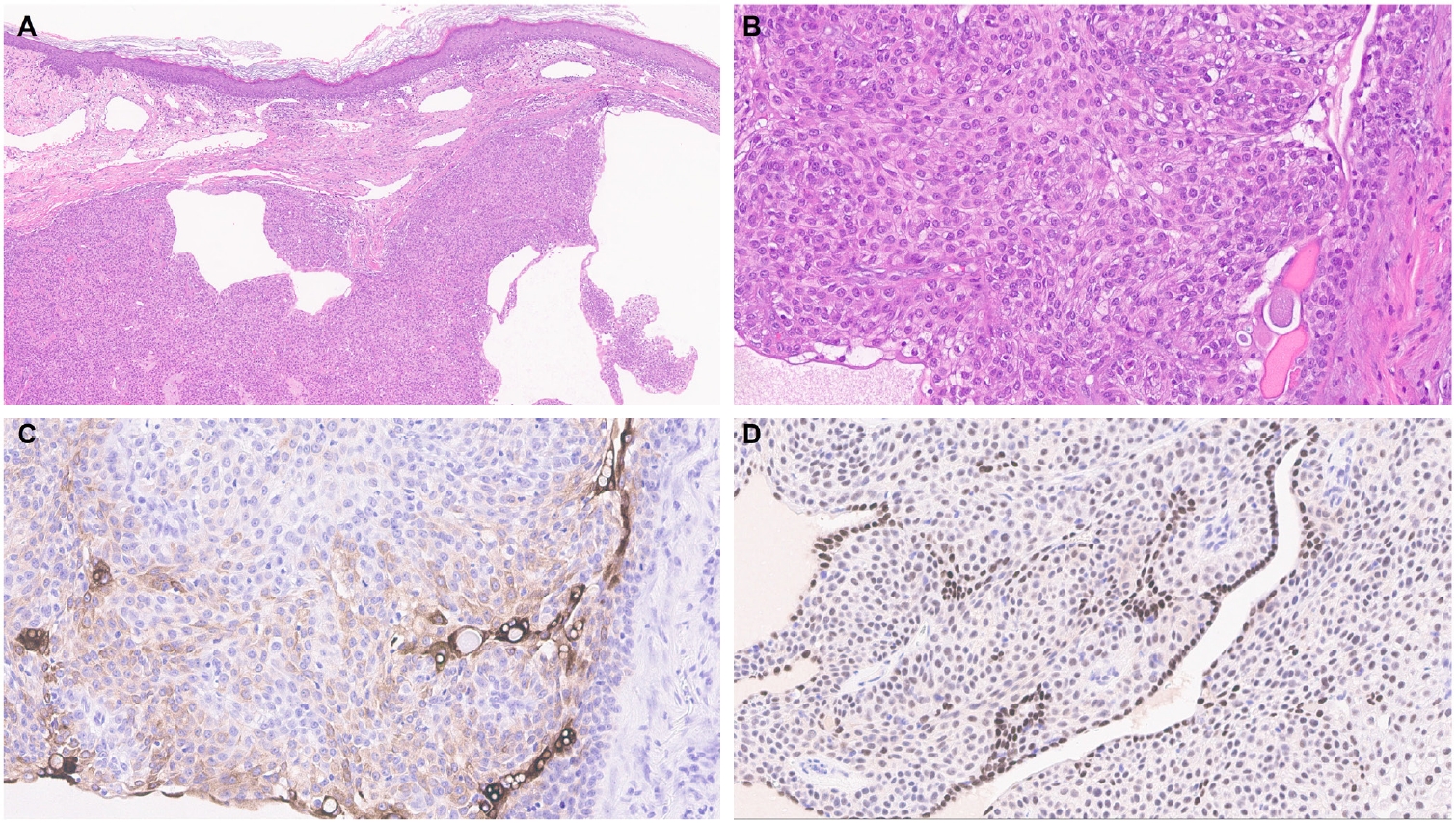

- One of the earliest and most promising applications of TRPS1 IHC in dermatopathology has been its supportive role in diagnosing MPDs and EMPDs [2-4,9]. This utility is grounded in the origin of Paget cells in MPDs, which are derived from the underlying ductal carcinoma of the breast. These cells exhibit strong epidermotropism within the nipple-areolar complex. Given that TRPS1 is highly expressed in nearly all breast carcinomas, including those with a triple-negative phenotype [1], it is not surprising that Paget cells in MPDs are also TRPS1-positive (Fig. 4). A seminal study confirmed this, demonstrating consistent TRPS1 expression in all MPD cases examined (100%; 24/24) [2].

- When evaluating a pagetoid intraepidermal neoplasm, such as MPD or EMPD, in the skin or nipple-areolar region, a panel of immunohistochemical studies is typically required to distinguish these entities from morphologic mimics, particularly pagetoid SCCIS and melanoma in situ (MIS). The reliable expression of TRPS1 in Paget cells is diagnostically helpful, particularly when interpreted alongside other markers such as CK7 (or Cam5.2), p63, and SOX10. For example, MPDs typically demonstrate immunoreactivity for CK7 (or Cam5.2) and TRPS1 (Fig. 4B), while lacking expression of p63 (or CK5/6) and SOX10 (or other melanocytic markers like Melan-A or HMB45). In contrast, SCCISs and MISs have distinct immunoprofiles. Although TRPS1 expression has been observed in SCCISs [2], this entity rarely involves the nipple-areolar complex. When SCCIS occurs at other anatomic sites, tumor cells are usually positive for p63 (or CK5/6) and negative for SOX10. Since low molecular weight cytokeratins such as CK7 and Cam5.2 can sometimes be expressed in SCCISs, especially those with prominent pagetoid features [33], their diagnostic utility in this context may be limited.

- MISs, on the other hand, typically express SOX10 while lacking CK7 and p63 expression. Importantly, MISs are consistently negative for TRPS1 [2], making TRPS1 a particularly useful marker in challenging cases. This is especially relevant in MPD cases arising from underlying triple-negative or metaplastic breast carcinomas, which may express SOX10 [18,19]—a well-documented diagnostic pitfall. In such scenarios, the strong and diffuse expression of TRPS1 in intraepidermal pagetoid cells can support a diagnosis of MPD, even in the presence of SOX10 positivity.

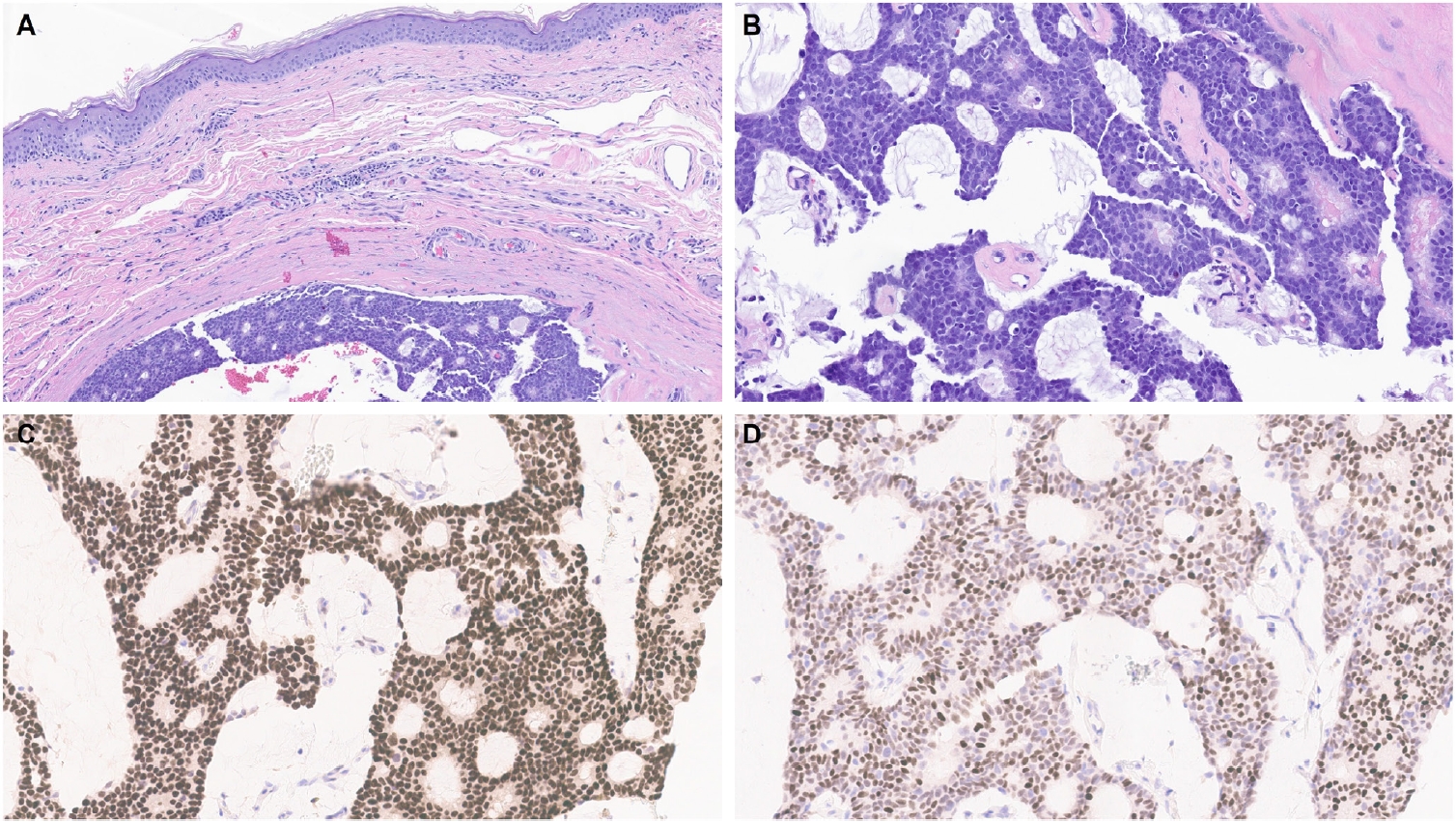

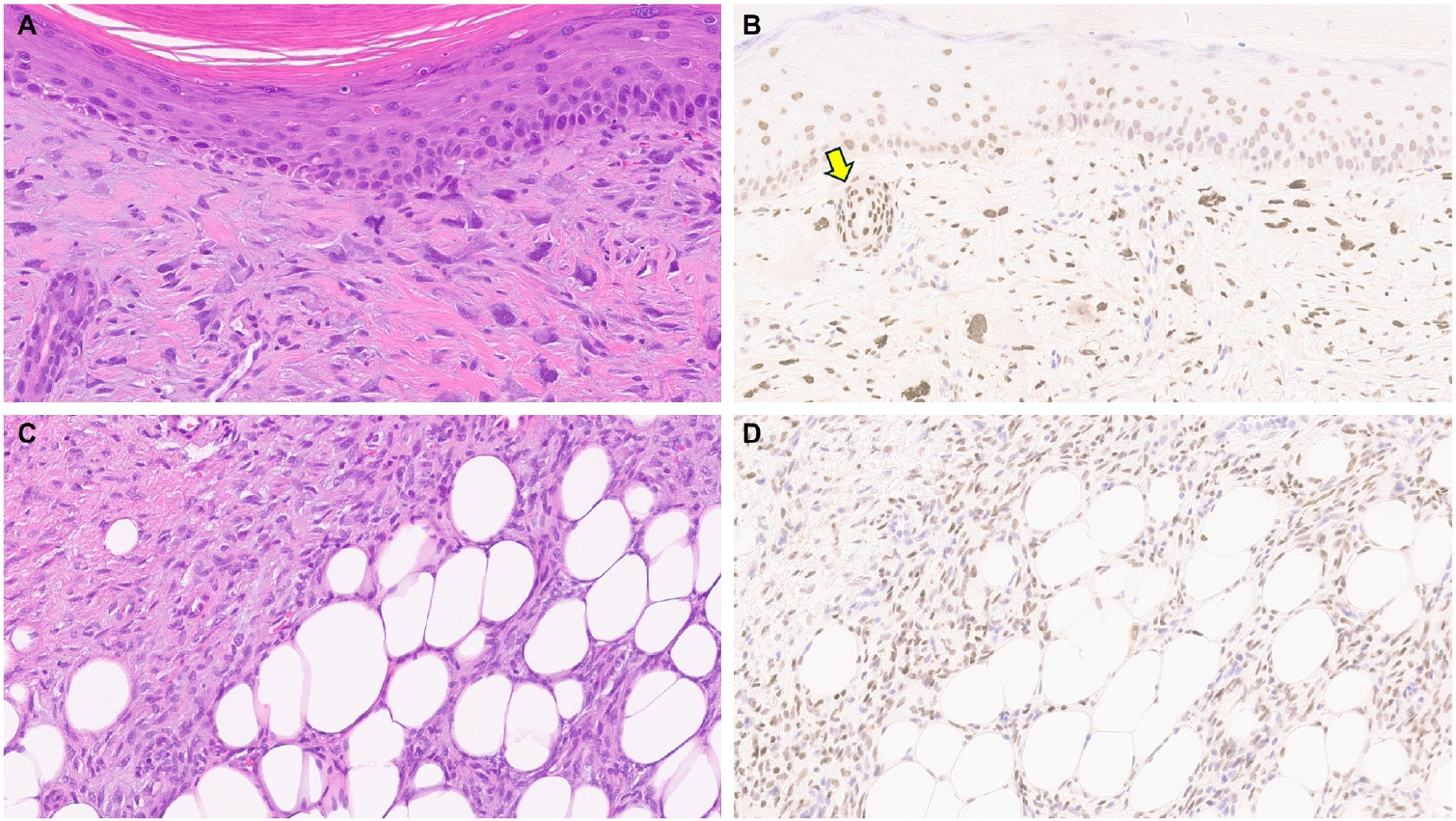

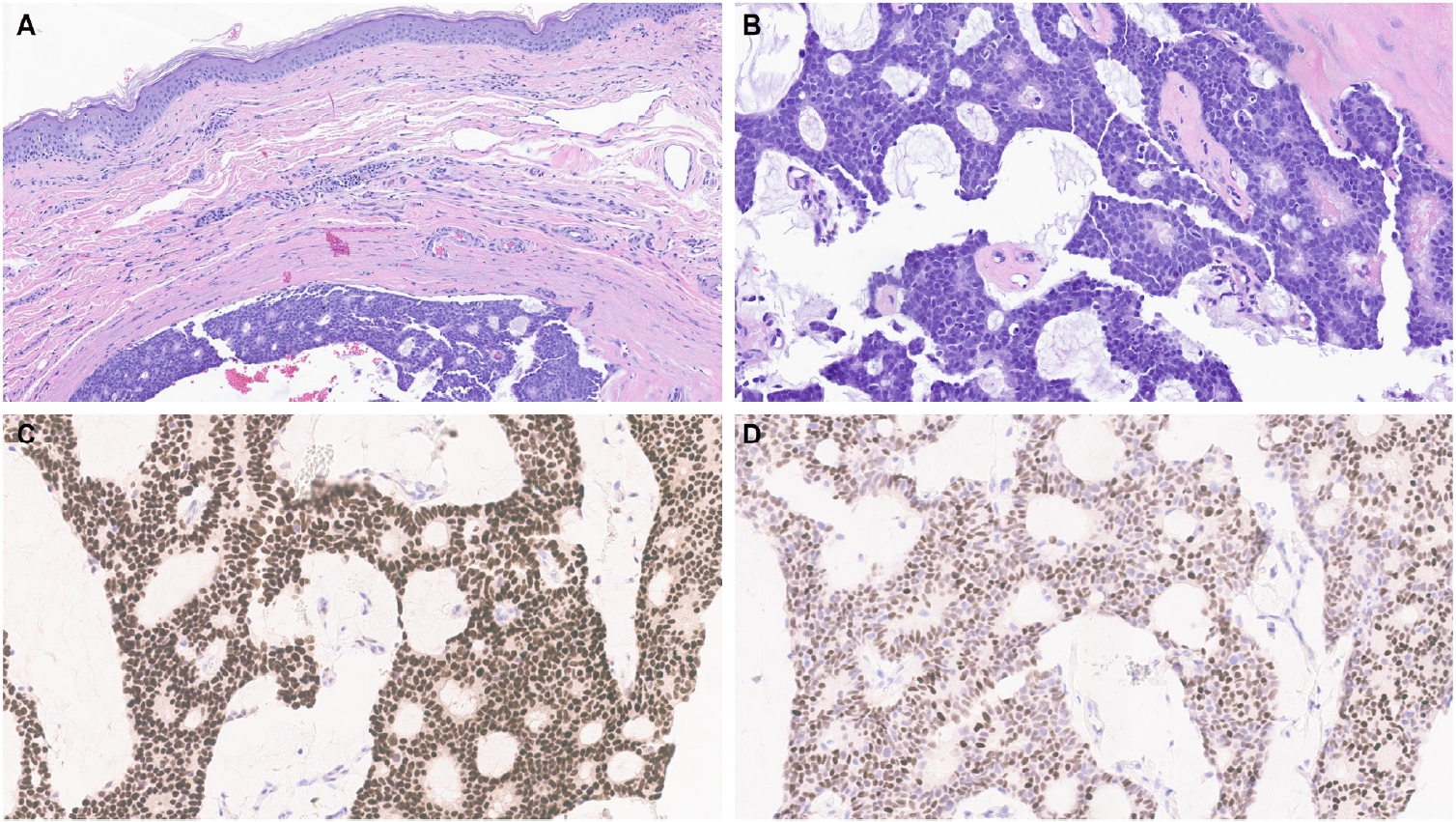

- Similar to MPD, recent studies have shown that the majority of EMPD cases—ranging from 88% to 100%—also exhibit strong and diffuse TRPS1 expression [2-4,9]. Three key findings have emerged from these studies [2-4,9]: (1) TRPS1 is both highly sensitive (100%) and specific (100%) for primary EMPD arising outside the perianal region, such as the groin/inguinal area and axilla (Fig. 5); (2) secondary EMPDs, which originate from underlying internal malignancies such as colorectal or urothelial carcinomas, consistently lack TRPS1 expression (Fig. 6); and (3) the majority of perianal primary EMPDs—up to 91%—also lack TRPS1 expression, mimicking the immunoprofile of secondary EMPDs.

- This third observation is especially diagnostically important. Given the high rate of TRPS1 negativity in perianal primary EMPDs, thorough clinical workup, including endoscopy or imaging, is essential to conclusively exclude an associated internal malignancy. Additional markers, such as CK20 and gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 (GCDFP-15), may aid in this distinction: a CK20-negative/GCDFP-15–positive immunoprofile may support a primary origin, while CK20 positivity with GCDFP-15 negativity leans toward a secondary source [34]. However, caution is warranted, as CK20 expression is not entirely specific—approximately one-third of perianal primary EMPDs can also express CK20 [34].

- A few additional tumor types fall within this category, all of which are associated with anogenital mammary-like glands. These include hidradenoma papilliferum (HP), fibroadenoma and phyllodes tumor of anogenital mammary-like glands, and adenocarcinoma of mammary gland type. HPs, believed to originate from anogenital mammary-like glands, most commonly occur in the vulva and only rarely in the perianal region. Given that native anogenital mammary-like glands demonstrate TRPS1 expression [9], it is not surprising that a recent study found consistent TRPS1 positivity in all HPs (100%; 9/9), except within intratumoral foci exhibiting oxyphilic metaplasia, which lacked expression [13].

- Due to the rarity of other neoplasms in this group, data on TRPS1 expression in tumors such as adenocarcinomas of mammary gland type remain limited. However, based on the authors’ limited experience, TRPS1 immunoreactivity has been observed in at least one case of adenocarcinoma of mammary gland type, although larger studies are needed to confirm and better characterize this finding.

TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN SITE-SPECIFIC ADNEXAL TUMORS

- MISs and invasive melanomas are essentially devoid of TRPS1 expression (Table 1) [1,2]. While benign melanocytic neoplasms such as common (banal) nevi have not been well studied with regard to TRPS1 immunoreactivity, they are also likely negative for TRPS1, given that normal epidermal melanocytes do not express this marker. However, the TRPS1 expression profile in other melanocytic neoplasms, including melanocytomas such as WNT-activated deep penetrating/plexiform melanocytomas and pigmented epithelioid melanocytomas, remains largely uncharacterized.

TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN MELANOCYTIC NEOPLASMS

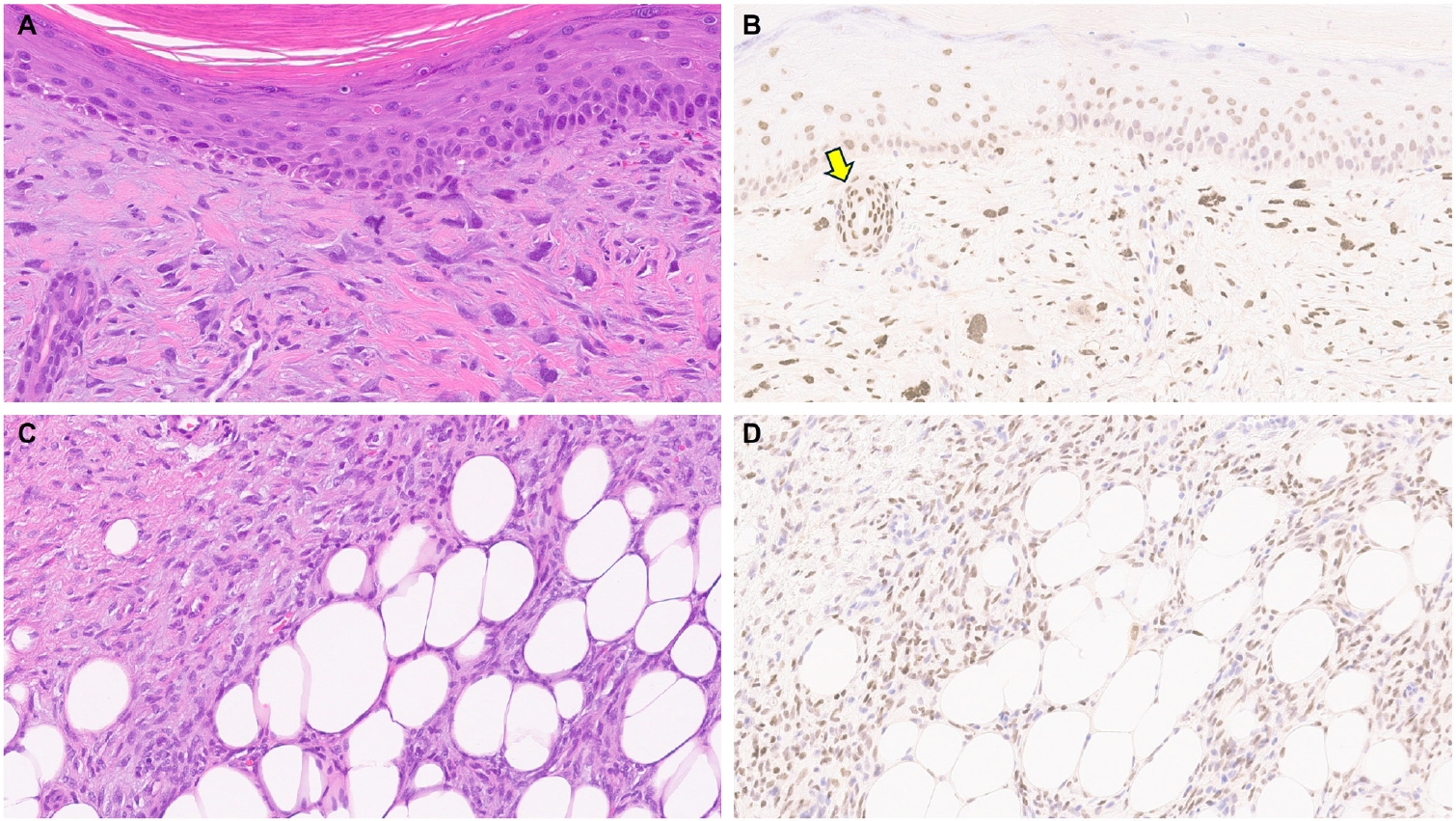

- Limited studies have explored TRPS1 immunoreactivity in non-epithelial neoplasms (Table 1). One recent study assessed TRPS1 expression in 135 cases of various cutaneous mesenchymal neoplasms and tumors of uncertain differentiation, including atypical fibroxanthomas (AFXs) (Fig. 7A, B). TRPS1 was frequently expressed in dermatofibromas (100%; 24/24), leiomyomas (100%; 8/8), AFXs/pleomorphic dermal sarcomas (PDSs) (95%; 20/21), leiomyosarcomas (75%; 6/8), and dermatofibrosarcomas protuberans (64%; 14/22) (Fig. 7C, D) [12]. Expression was less frequent in neurofibromas (29%; 5/17), Kaposi sarcomas (25%; 2/8), and angiosarcomas (15%; 3/20), and was completely absent in perineuriomas [12]. Considering both the proportion and intensity of TRPS1 expression, AFXs/PDSs exhibited the highest median H-score of 240, whereas vascular neoplasms and peripheral nerve sheath tumors had consistently low median H-scores below 10 [12].

- The morphologic differential diagnosis of AFX often includes poorly differentiated or sarcomatoid SCC, melanoma, angiosarcoma, and leiomyosarcoma. The aforementioned study also examined the potential of TRPS1 in distinguishing AFXs from these morphologic mimics. While significant differences in H-scores were observed between AFXs and angiosarcomas (p < .001), melanomas (p < .001), and leiomyosarcomas (p = .029), no significant difference was noted when compared to sarcomatoid SCCs, suggesting limited discriminatory value of TRPS1 in this context [12].

- Another recent study highlighted that a subset of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors also expresses TRPS1, albeit generally with weak intensity [20]. In contrast, other benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors, such as schwannomas and neurofibromas, consistently lacked TRPS1 expression [20].

- Together, these studies provide new insights into TRPS1 expression patterns in a subset of cutaneous mesenchymal neoplasms and tumors of uncertain differentiation. This extends beyond prior research primarily focused on epithelial tumors and underscores potential limitations associated with TRPS1 IHC.

- Finally, TRPS1 expression is not confined to neoplastic processes in the skin. Similar to its expression in cutaneous mesenchymal neoplasms of fibroblastic, myofibroblastic, or fibrohistiocytic origin, TRPS1 is also found in non-neoplastic stromal cells like fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, particularly in wound healing and scar formation [35]. This may be linked to TRPS1’s role as a key regulator in tissue regeneration. Notably, down-regulation of TRPS1 has been shown to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis in various cancer types by repressing FOXA1, a negative regulator of EMT [36].

TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN CUTANEOUS MESENCHYMAL NEOPLASMS

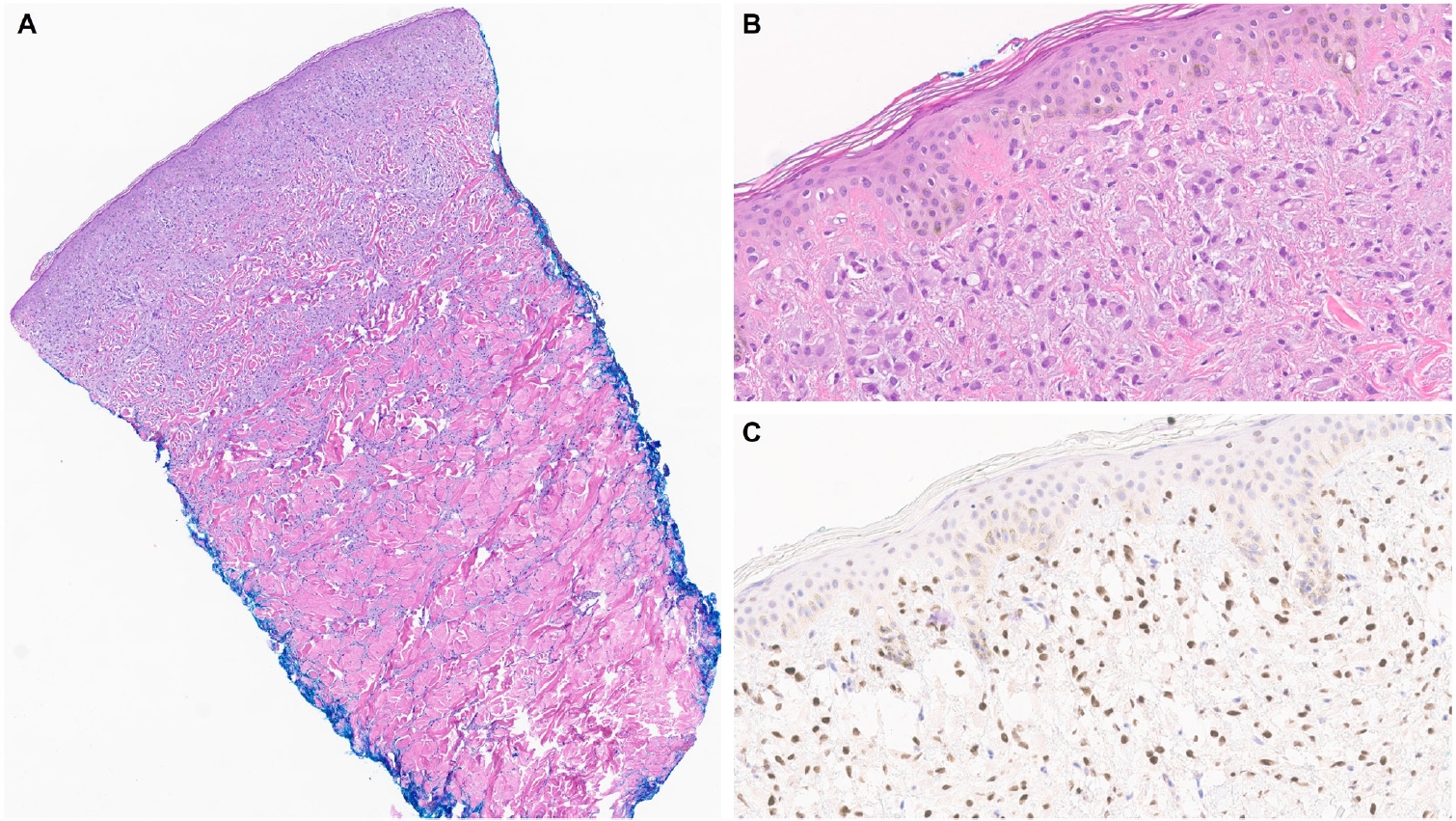

- Given the well-documented high frequency of TRPS1 expression in breast carcinomas [1], it is not surprising that 95%–100% of metastatic mammary carcinomas involving the skin demonstrate strong and diffuse TRPS1 immunoreactivity (Table 1) [9,14]. In contrast, only focal and weak TRPS1 immunoreactivity may occasionally be observed in metastatic carcinomas of pulmonary (particularly SCCs), gynecologic, or renal origin (Table 1) [9,14]. Notably, carcinomas originating from the gastrointestinal tract, such as colonic and gastric adenocarcinomas, or from the prostate, typically lack TRPS1 expression (Table 1) [9,14]. Therefore, in the appropriate morphologic and immunophenotypic context (e.g., CK7+/GATA3+), strong and diffuse TRPS1 expression in a suspected case of cutaneous metastasis can support a mammary origin (Fig. 8).

- However, a key diagnostic limitation is that TRPS1 expression does not distinguish between a primary cutaneous adnexal carcinoma, including primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma, and a cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma, as both can exhibit strong and diffuse TRPS1 positivity. In such cases, thorough clinicopathologic correlation, including imaging studies, is essential for accurate classification.

TRPS1 EXPRESSION IN CUTANEOUS METASTATIC CARCINOMAS

- It is well recognized that the initially reported sensitivity and specificity of a new immunohistochemical marker often decline over time as its use becomes more widespread and as additional data and real-world experiences accumulate. TRPS1 IHC is no exception. Initially regarded as a highly sensitive and specific marker for breast carcinomas [1], TRPS1 has since been shown to be expressed in a broader range of cutaneous neoplasms, challenging its specificity.

- As demonstrated throughout this review, TRPS1 expression is not exclusive to any single cutaneous tumor type. Nevertheless, when interpreted in conjunction with conventional markers and within the proper morphologic and immunophenotypic context, TRPS1 can offer valuable diagnostic insight. Notable examples include its use in diagnosing MPD (TRPS1+/CK7+/SOX10-/p63–), primary EMPD (TRPS1+/CK7+/SOX10–/p63–), primary cutaneous NUT adnexal carcinoma (TRPS1+/SOX10+/NUT+), EMPSGC (TRPS1+/INSM1+), and cutaneous metastases of mammary carcinoma (TRPS1+/CK7+/GATA3+). Although immunohistochemical studies are typically not necessary to differentiate SCCs from BCCs, the stark contrast in TRPS1 immunoreactivity (TRPS1+ in SCCs and TRPS1– in BCCs) may possibly provide additional diagnostic value.

- We hope this review has provided a comprehensive and practical overview of the diagnostic utility and limitations of TRPS1 in dermatopathology. Ultimately, it is critical to emphasize that immunohistochemical findings must always be interpreted in the context of the overall morphologic features, and no single marker, regardless of its perceived sensitivity or specificity, should be used in isolation.

CONCLUSION

Ethics Statement

All procedures performed in the current review were approved by the IRB of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (IRB#: 2022-0662) in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Formal written informed consent was not required with a waiver by the appropriate IRB.

Availability of Data and Material

The data of this review are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: WCC. Data curation: MHA. Formal analysis: MHA. Funding acquisition: WCC. Investigation: all authors. Methodology: WCC. Project administration: WCC. Resources: WCC. Software: N/A. Supervision: WCC. Validation: all authors. Visualization: all authors. Writing—original draft preparation: all authors. Writing—review & editing: all authors. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

This review was supported in part by the Institutional Start-up Funds from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center awarded to WCC.

| Category | Type | TRPS1 expression patterns | Potential diagnostic utility and other key points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal skin | Eccrine glands, acrosyringia, matrical cells, mesenchymal cells of dermal papillae [2,6] | Strong (3+) | Serve as ideal internal controls |

| Anogenital mammary-like glands [9] | Strong (3+) | - | |

| Sebocytes of sebaceous glands [2,6] | Weak-to-moderate (1+ to 2+) | - | |

| Outer and inner root sheaths of hair follicles [2,6] | Weak-to-strong (1+ to 3+) | - | |

| Epidermal keratinocytes in stratum spinosum [2,6] | Weak-to-moderate (1+ to 2+) | - | |

| Epidermal keratinocytes in stratum basale [2,6] | Negative | May explain the frequent absence of TRPS1 expression in basal cell carcinomas | |

| Apocrine glands [2,6] | Negative | - | |

| Non-adnexal epithelial neoplasms | Squamous cell carcinoma [2,6] | Moderate-to-strong (2+ to 3+); patchy-to-diffuse | May provide potential diagnostic utility in distinguishing squamous cell carcinomas from basal cell carcinomas |

| Basal cell carcinoma [5,6] | Negative (typically); only focal when present | May provide potential diagnostic utility in distinguishing basal cell carcinomas from squamous cell carcinomas | |

| Merkel cell carcinoma [5,6] | Negative | Helps distinguish Merkel cell carcinomas (TRPS1–/INSM1+) from endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinomas (TRPS1+/INSM1+) | |

| Adnexal neoplasms with apocrine and eccrine differentiation | Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma [5,6] | Strong (3+); diffuse | Helps distinguish endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinomas (TRPS1+/INSM1+) from basal cell carcinomas (TRPS1–/INSM1–) and Merkel cell carcinomas (TRPS1–/INSM1+) |

| Primary cutaneous NUT adnexal carcinoma [15,16] | Strong (3+); diffuse | Helps distinguish primary cutaneous NUT adnexal carcinomas (TRPS1+/SOX10+/NUT+) from basal cell carcinomas (TRPS1–/SOX10–/NUT–) | |

| Benign (poroma, hidradenoma, spiradenoma, cylindroma, syringoma, syringocystadenoma papilliferum) | Weak-to-strong (1+ to 3+); focal-to-diffuse | Lacks diagnostic utility in distinguishing these tumor types from their morphologic mimics | |

| Malignant (porocarcinoma, hidradenocarcinoma, digital papillary adenocarcinoma, squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma) [5-7,9,10,15,16] | Weak-to-strong (1+ to 3+); focal-to-diffuse | Lacks diagnostic utility in distinguishing these tumor types from their morphologic mimics | |

| Primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma [11,17] | Negative (typically) | Diffuse expression reported in one rare case with a RARA::NPEPPS fusion [11] | |

| Microcystic adnexal carcinoma [7] | Negative | - | |

| Adnexal neoplasms with follicular differentiation | Benign (trichoepithelioma, trichoblastoma, trichilemmoma, trichofolliculoma, pilar sheath acanthoma, proliferating pilar tumor, pilometricoma) | Weak-to-strong (1+ to 3+); focal-to-diffuse | Largely lacks diagnostic utility in distinguishing these tumor types from their morphologic mimics |

| Malignant (malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor, trichilemmal carcinoma, trichoblastic carcinoma) [6,8,9] | Weak-to-strong (1+ to 3+); focal-to-diffuse | May be useful to highlight the papillary mesenchymal bodies of trichoepitheliomas and trichoblastomas, which exhibit strong (3+) TRPS1 expression | |

| Adnexal neoplasms with sebaceous differentiation | Sebaceous adenoma, sebaceoma, sebaceous carcinoma [6,9] | Weak-to-moderate (1+ to 2+); focal-to-diffuse | Lacks diagnostic utility in distinguishing sebaceous adenomas from sebaceous carcinomas |

| Site-specific adnexal neoplasms | Mammary Paget disease [2-4,9] | Strong (3+); diffuse | Helps distinguish mammary Paget diseases (TRPS1+/p63–/SOX10–) from melanomas in situ (TRPS1–/p63–/SOX10+) and pagetoid squamous cell carcinomas in situ (TRPS1+/p63+/SOX10–) |

| Primary extramammary Paget disease arising in non-perianal cutaneous sites [2-4,9] | Strong (3+); diffuse | Helps distinguish primary extramammary Paget diseases (TRPS1+/p63–/SOX10–) from melanomas in situ (TRPS1–/p63–/SOX10+) and pagetoid squamous cell carcinomas in situ (TRPS1+/p63+/SOX10–) | |

| The presence of TRPS1 expression is highly sensitive (100%) and specific (100%) for primary extramammary Paget disease of non-perianal cutaneous origin and essentially rules out secondary extramammary Paget disease | |||

| Primary extramammary Paget disease arising in the perianal region [2-4,9] | Negative (typically) | The immunoprofile (TRPS1–) mimics that of secondary extramammary Paget disease (TRPS1–), invariably requiring additional clinical workup (e.g., endoscopy, imaging studies) to completely rule out an internal malignancy | |

| Secondary extramammary Paget disease [2-4,9] | Negative | The lack of TRPS1 expression strongly supports a diagnosis of secondary extramammary Paget disease over primary extramammary Paget disease, except for lesions arising in the perianal region | |

| Hidradenoma papilliferum [13] | Strong (3+); diffuse | - | |

| Melanocytic neoplasms | Melanoma situ and invasive melanoma [1,2] | Negative | Helps distinguish melanomas in situ (TRPS1–/SOX10+) from mammary and extramammary Paget diseases (TRPS1+/SOX10–), including mammary Paget diseases secondary to underlying triple-negative breast carcinomas, which can be positive for SOX10 (TRPS1+/SOX10+) [18,19] |

| Mesenchymal neoplasms | Atypical fibroxanthoma/pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, angiosarcoma, dermatofibroma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, Kaposi sarcoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, neurofibroma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor [12,20] | Weak-to-strong (1+ to 3+); focal-to-diffuse | Lacks diagnostic utility in distinguishing these tumor types from their morphologic mimics |

| Atypical fibroxanthomas/pleomorphic dermal sarcomas exhibit the highest median H-score of 240, while vascular neoplasms and peripheral nerve sheath tumors consistently show low median H-scores below 10 [12] | |||

| Schwannoma [20] | Negative | - | |

| Cutaneous metastatic carcinomas | Carcinoma of mammary origin [1,9,14] | Strong (3+); diffuse | The presence of strong and diffuse TRPS1 expression helps support a diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma of mammary origin in the appropriate morphologic and immunophenotypic (CK7+/GATA3+) context |

| Carcinomas of pulmonary, gynecological, or renal origin [9,14] | Weak (1+); focal (occasionally) | - | |

| Carcinomas of gastrointestinal or prostatic origin [9,14] | Negative | - |

- 1. Ai D, Yao J, Yang F, et al. TRPS1: a highly sensitive and specific marker for breast carcinoma, especially for triple-negative breast cancer. Mod Pathol 2021; 34: 710-9. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 2. Cho WC, Ding Q, Wang WL, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of TRPS1 in mammary Paget disease, extramammary Paget disease, and their close histopathologic mimics. J Cutan Pathol 2023; 50: 434-40. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 3. Liu YA, Collins K, Aung PP, et al. TRPS1 expression in primary and secondary extramammary Paget diseases: an immunohistochemical analysis of 93 cases. Hum Pathol 2024; 143: 5-9. ArticlePubMed

- 4. Cook EE, Harrison BT, Hirsch MS. TRPS1 expression is sensitive and specific for primary extramammary Paget disease. Histopathology 2023; 83: 104-8. ArticlePubMed

- 5. Liu YA, Cho WC. TRPS1 expression in endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma: diagnostic utility and pitfalls. Am J Dermatopathol 2024; 46: 133-5. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Liu YA, Aung PP, Wang Y, et al. TRPS1 expression in non-melanocytic cutaneous neoplasms: an immunohistochemical analysis of 200 cases. J Pathol Transl Med 2024; 58: 72-80. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 7. Zengin HB, Bui CM, Rybski K, Pukhalskaya T, Yildiz B, Smoller BR. TRPS1 is differentially expressed in a variety of malignant and benign cutaneous sweat gland neoplasms. Dermatopathology (Basel) 2023; 10: 75-85. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Rybski KJ, Zengin HB, Smoller BR. TRPS1: a marker of follicular differentiation. Dermatopathology (Basel) 2023; 10: 173-83. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Taniguchi K, Goto K, Yabushita H, Yamasaki R, Ichimura K. Transcriptional repressor GATA binding 1 (TRPS1) immunoexpression in normal skin tissues and various cutaneous tumors. J Cutan Pathol 2023; 50: 1006-13. ArticlePubMed

- 10. Alsawas M, Muhaj FF, Aung PP, Nagarajan P, Cho WC. Syringocystadenoma papilliferum-like features in poroma: an unusual morphologic pattern of poroma or true synchronous occurrence of 2 distinct neoplasms? Am J Dermatopathol 2024; 46: 871-4. ArticlePubMed

- 11. Lenskaya V, Yang RK, Cho WC. Primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma with RARA::NPEPPS fusion. J Cutan Pathol 2024; 51: 419-23. ArticlePubMed

- 12. Kim MJ, Liu YA, Wang Y, Ning J, Cho WC. TRPS1 expression is frequently seen in a subset of cutaneous mesenchymal neoplasms and tumors of uncertain differentiation: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Dermatopathology (Basel) 2024; 11: 200-8. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Velthof L, Van Dorpe J, Tummers P, Creytens D, Van de Vijver K. TRPS1 is consistently expressed in hidradenoma papilliferum. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2025; 44: 99-103. ArticlePubMed

- 14. Boulogeorgou K, Topalidis C, Koletsa T, Karayannopoulou G, Kanitakis J. Expression of TRPS1 in metastatic tumors of the skin: an immunohistochemical study of 72 cases. Dermatopathology (Basel) 2024; 11: 293-302. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Ibrahim E, Yang RK, Gubbiotti MA, Prieto VG, Cho WC. Primary cutaneous NUT adnexal carcinoma with BRD4::NUTM1 fusion: a 19-year follow-up. Am J Dermatopathol 2025; 47: 731-3. ArticlePubMed

- 16. Goto K, Kukita Y, Hishima T, et al. Primary cutaneous NUT carcinoma: clinicopathologic and genetic study of 4 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2024; 48: 942-52. ArticlePubMed

- 17. Wang J, Peng Y, Sun H, et al. TRPS1 and GATA3 expression in invasive breast carcinoma with apocrine differentiation. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2024; 148: 200-5. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 18. Cimino-Mathews A, Subhawong AP, Elwood H, et al. Neural crest transcription factor Sox10 is preferentially expressed in triple-negative and metaplastic breast carcinomas. Hum Pathol 2013; 44: 959-65. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 19. Rolim I, Rafael M, Robson A, Costa Rosa J. Pigmented epidermotropic breast carcinoma: a diagnostic pitfall mimicking melanoma a case report and literature review. Int J Surg Pathol 2024; 32: 386-93. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 20. Lazcano R, Ingram DR, Panse G, Lazar AJ, Wang WL, Cloutier JM. Trps1 expression in MPNST is correlated with PRC2 inactivation and loss of H3K27me3. Hum Pathol 2024; 151: 105632.ArticlePubMed

- 21. Youssef KK, Van Keymeulen A, Lapouge G, et al. Identification of the cell lineage at the origin of basal cell carcinoma. Nat Cell Biol 2010; 12: 299-305. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 22. Cazzato G, Daruish M, Fortarezza F, et al. Gene fusion-driven cutaneous adnexal neoplasms: an updated review emphasizing molecular characteristics. Am J Dermatopathol 2025; 47: 453-61. ArticlePubMed

- 23. Flieder A, Koerner FC, Pilch BZ, Maluf HM. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma: a cutaneous neoplasm analogous to solid papillary carcinoma of breast. Am J Surg Pathol 1997; 21: 1501-6. ArticlePubMed

- 24. Agni M, Raven ML, Bowen RC, et al. An update on endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma: clinicopathologic study of 63 cases and comparative analysis. Am J Surg Pathol 2020; 44: 1005-16. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 25. Quattrochi B, Russell-Goldman E. Utility of insulinoma-associated protein 1 (INSM1) and mucin 2 (MUC2) immunohistochemistry in the distinction of endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma from morphologic mimics. Am J Dermatopathol 2022; 44: 92-7. ArticlePubMed

- 26. Parra O, Linos K, Yan S, Lilo M, LeBlanc RE. Comparative performance of insulinoma-associated protein 1 (INSM1) and routine immunohistochemical markers of neuroendocrine differentiation in the diagnosis of endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol 2021; 48: 41-6. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 27. Do J, Wang Y, Aung PP, et al. INSM1: a highly sensitive marker for primary and metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma, superior to SOX11, pancytokeratin, and CK20. Hum Pathol 2025; 160: 105838.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Legrand M, Louveau B, Osio A, et al. Primary cutaneous NUT adnexal carcinoma: morphologic, genetic and methylation analysis of seven new cases with comparison to extracutaneous NUT carcinoma and NUTM1-rearranged porocarcinoma. Histopathology 2025; 87: 375-87. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 29. Sekine S, Kiyono T, Ryo E, et al. Recurrent YAP1-MAML2 and YAP1-NUTM1 fusions in poroma and porocarcinoma. J Clin Invest 2019; 129: 3827-32. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 30. Russell-Goldman E, Hornick JL, Hanna J. Utility of YAP1 and NUT immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of porocarcinoma. J Cutan Pathol 2021; 48: 403-10. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 31. Cassarino DS, Su A, Robbins BA, Altree-Tacha D, Ra S. SOX10 immunohistochemistry in sweat ductal/glandular neoplasms. J Cutan Pathol 2017; 44: 544-7. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 32. Sellheyer K, Nelson P. Follicular stem cell marker PHLDA1 (TDAG51) is superior to cytokeratin-20 in differentiating between trichoepithelioma and basal cell carcinoma in small biopsy specimens. J Cutan Pathol 2011; 38: 542-50. ArticlePubMed

- 33. Clarke LE, Conway AB, Warner NM, Barnwell PN, Sceppa J, Helm KF. Expression of CK7, Cam 5.2 and Ber-Ep4 in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol 2013; 40: 646-50. ArticlePubMed

- 34. Goldblum JR, Hart WR. Perianal Paget's disease: a histologic and immunohistochemical study of 11 cases with and without associated rectal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1998; 22: 170-9. ArticlePubMed

- 35. Cho WC, Nagarajan P, Ding Q, Prieto VG, Torres-Cabala CA. Trichorhinophalangeal syndrome type 1-positive cells in breast dermal granulation tissues and scars: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Am J Dermatopathol 2022; 44: 964-7. ArticlePubMed

- 36. Huang JZ, Chen M, Zeng M, et al. Down-regulation of TRPS1 stimulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis through repression of FOXA1. J Pathol 2016; 239: 186-96. ArticlePubMed

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 8.

| Category | Type | TRPS1 expression patterns | Potential diagnostic utility and other key points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal skin | Eccrine glands, acrosyringia, matrical cells, mesenchymal cells of dermal papillae [2,6] | Strong (3+) | Serve as ideal internal controls |

| Anogenital mammary-like glands [9] | Strong (3+) | - | |

| Sebocytes of sebaceous glands [2,6] | Weak-to-moderate (1+ to 2+) | - | |

| Outer and inner root sheaths of hair follicles [2,6] | Weak-to-strong (1+ to 3+) | - | |

| Epidermal keratinocytes in stratum spinosum [2,6] | Weak-to-moderate (1+ to 2+) | - | |

| Epidermal keratinocytes in stratum basale [2,6] | Negative | May explain the frequent absence of TRPS1 expression in basal cell carcinomas | |

| Apocrine glands [2,6] | Negative | - | |

| Non-adnexal epithelial neoplasms | Squamous cell carcinoma [2,6] | Moderate-to-strong (2+ to 3+); patchy-to-diffuse | May provide potential diagnostic utility in distinguishing squamous cell carcinomas from basal cell carcinomas |

| Basal cell carcinoma [5,6] | Negative (typically); only focal when present | May provide potential diagnostic utility in distinguishing basal cell carcinomas from squamous cell carcinomas | |

| Merkel cell carcinoma [5,6] | Negative | Helps distinguish Merkel cell carcinomas (TRPS1–/INSM1+) from endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinomas (TRPS1+/INSM1+) | |

| Adnexal neoplasms with apocrine and eccrine differentiation | Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma [5,6] | Strong (3+); diffuse | Helps distinguish endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinomas (TRPS1+/INSM1+) from basal cell carcinomas (TRPS1–/INSM1–) and Merkel cell carcinomas (TRPS1–/INSM1+) |

| Primary cutaneous NUT adnexal carcinoma [15,16] | Strong (3+); diffuse | Helps distinguish primary cutaneous NUT adnexal carcinomas (TRPS1+/SOX10+/NUT+) from basal cell carcinomas (TRPS1–/SOX10–/NUT–) | |

| Benign (poroma, hidradenoma, spiradenoma, cylindroma, syringoma, syringocystadenoma papilliferum) | Weak-to-strong (1+ to 3+); focal-to-diffuse | Lacks diagnostic utility in distinguishing these tumor types from their morphologic mimics | |

| Malignant (porocarcinoma, hidradenocarcinoma, digital papillary adenocarcinoma, squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma) [5-7,9,10,15,16] | Weak-to-strong (1+ to 3+); focal-to-diffuse | Lacks diagnostic utility in distinguishing these tumor types from their morphologic mimics | |

| Primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma [11,17] | Negative (typically) | Diffuse expression reported in one rare case with a RARA::NPEPPS fusion [11] | |

| Microcystic adnexal carcinoma [7] | Negative | - | |

| Adnexal neoplasms with follicular differentiation | Benign (trichoepithelioma, trichoblastoma, trichilemmoma, trichofolliculoma, pilar sheath acanthoma, proliferating pilar tumor, pilometricoma) | Weak-to-strong (1+ to 3+); focal-to-diffuse | Largely lacks diagnostic utility in distinguishing these tumor types from their morphologic mimics |

| Malignant (malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor, trichilemmal carcinoma, trichoblastic carcinoma) [6,8,9] | Weak-to-strong (1+ to 3+); focal-to-diffuse | May be useful to highlight the papillary mesenchymal bodies of trichoepitheliomas and trichoblastomas, which exhibit strong (3+) TRPS1 expression | |

| Adnexal neoplasms with sebaceous differentiation | Sebaceous adenoma, sebaceoma, sebaceous carcinoma [6,9] | Weak-to-moderate (1+ to 2+); focal-to-diffuse | Lacks diagnostic utility in distinguishing sebaceous adenomas from sebaceous carcinomas |

| Site-specific adnexal neoplasms | Mammary Paget disease [2-4,9] | Strong (3+); diffuse | Helps distinguish mammary Paget diseases (TRPS1+/p63–/SOX10–) from melanomas in situ (TRPS1–/p63–/SOX10+) and pagetoid squamous cell carcinomas in situ (TRPS1+/p63+/SOX10–) |

| Primary extramammary Paget disease arising in non-perianal cutaneous sites [2-4,9] | Strong (3+); diffuse | Helps distinguish primary extramammary Paget diseases (TRPS1+/p63–/SOX10–) from melanomas in situ (TRPS1–/p63–/SOX10+) and pagetoid squamous cell carcinomas in situ (TRPS1+/p63+/SOX10–) | |

| The presence of TRPS1 expression is highly sensitive (100%) and specific (100%) for primary extramammary Paget disease of non-perianal cutaneous origin and essentially rules out secondary extramammary Paget disease | |||

| Primary extramammary Paget disease arising in the perianal region [2-4,9] | Negative (typically) | The immunoprofile (TRPS1–) mimics that of secondary extramammary Paget disease (TRPS1–), invariably requiring additional clinical workup (e.g., endoscopy, imaging studies) to completely rule out an internal malignancy | |

| Secondary extramammary Paget disease [2-4,9] | Negative | The lack of TRPS1 expression strongly supports a diagnosis of secondary extramammary Paget disease over primary extramammary Paget disease, except for lesions arising in the perianal region | |

| Hidradenoma papilliferum [13] | Strong (3+); diffuse | - | |

| Melanocytic neoplasms | Melanoma situ and invasive melanoma [1,2] | Negative | Helps distinguish melanomas in situ (TRPS1–/SOX10+) from mammary and extramammary Paget diseases (TRPS1+/SOX10–), including mammary Paget diseases secondary to underlying triple-negative breast carcinomas, which can be positive for SOX10 (TRPS1+/SOX10+) [18,19] |

| Mesenchymal neoplasms | Atypical fibroxanthoma/pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, angiosarcoma, dermatofibroma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, Kaposi sarcoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, neurofibroma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor [12,20] | Weak-to-strong (1+ to 3+); focal-to-diffuse | Lacks diagnostic utility in distinguishing these tumor types from their morphologic mimics |

| Atypical fibroxanthomas/pleomorphic dermal sarcomas exhibit the highest median H-score of 240, while vascular neoplasms and peripheral nerve sheath tumors consistently show low median H-scores below 10 [12] | |||

| Schwannoma [20] | Negative | - | |

| Cutaneous metastatic carcinomas | Carcinoma of mammary origin [1,9,14] | Strong (3+); diffuse | The presence of strong and diffuse TRPS1 expression helps support a diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma of mammary origin in the appropriate morphologic and immunophenotypic (CK7+/GATA3+) context |

| Carcinomas of pulmonary, gynecological, or renal origin [9,14] | Weak (1+); focal (occasionally) | - | |

| Carcinomas of gastrointestinal or prostatic origin [9,14] | Negative | - |

TRPS1, trichorhinophalangeal syndrome type 1; INSM1, insulinoma-associated protein 1; CK, cytokeratin.

E-submission

E-submission

Cite this Article

Cite this Article