Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Pathol Transl Med > Volume 48(1); 2014 > Article

-

Brief Case Report

Benign Indolent CD56-Positive NK-Cell Lymphoproliferative Lesion Involving Gastrointestinal Tract in an Adolescent - Jaemoon Koh, Heounjeong Go1, Won Ae Lee2, Yoon Kyung Jeon

-

Korean Journal of Pathology 2014;48(1):73-76.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2014.48.1.73

Published online: February 25, 2014

Department of Pathology, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

1Department of Pathology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

2Department of Pathology, Dankook University Hospital, Dankook University College of Medicine, Cheonan, Korea.

- Corresponding Author: Yoon Kyung Jeon, M.D. Department of Pathology, Seoul National University Hospital, 103 Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul 110-799, Korea. Tel: +82-2-2072-2788, Fax: +82-2-743-5530, junarplus@chol.com

• Received: April 22, 2013 • Revised: May 24, 2013 • Accepted: May 29, 2013

© 2014 The Korean Society of Pathologists/The Korean Society for Cytopathology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

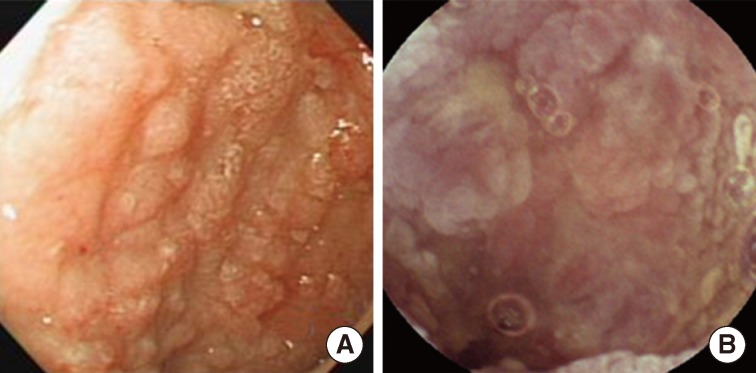

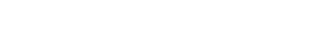

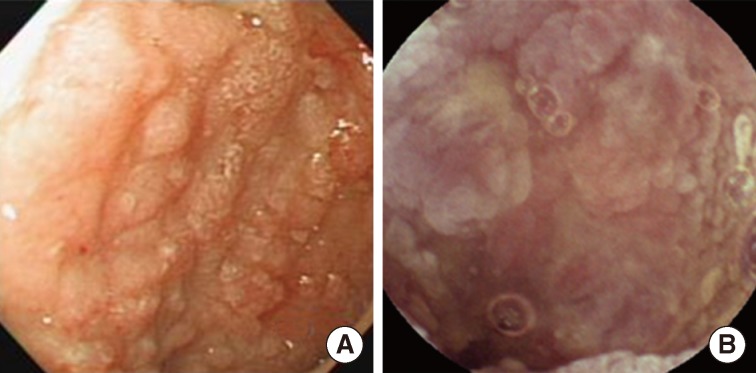

- A fourteen-year-old boy was admitted to our hospital due to chronic recurrent vomiting and abdominal discomfort, which began several months previously and intensified to occurrence of vomiting once a day. He also had intermittent diarrhea without severe abdominal pain or fever. His height and weight were both estimated to place him in the lowest 3% of the growth curve for his age. There was no remarkable family history except for hyperthyroidism in his farther. Initially, under the impression of eosinophilic gastroenteritis, prednisolone therapy was administered. However after short-term improvement of symptoms, vomiting recurred. After colonoscopic biopsy, he was presumptively diagnosed with EATL. He was readmitted to our hospital for further workup and nutritional therapy. Endoscopic examinations including capsule endoscopy revealed multiple small lesions with mucosal nodularity and hyperemic change in esophagus, stomach, duodenum, small intestine, and colon with several erosions of the intestine (Fig. 1). Computed tomography scan revealed diffuse thickening of the distal esophageal wall, stomach, duodenum and small intestine, slightly enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes and borderline-sized (10 cm) splenomegaly. On positron emission tomography scan, the only notable finding was mild fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in GI tract, suggestive of physiologic change. Laboratory tests showed mild leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 12,540/µL) with a differential count within normal range, anemia (hemoglobin, 7.4 g/dL), hypoferritinemia (3.88 ng/mL), hypocalcemia (5.5 mg/dL), hypoproteinemia (total protein 3.3 g/dL), and hypoalbuminemia (1.7 g/dL). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was elevated up to 372 IU/L. The presumptive diagnosis of EATL led physicians to perform serologic tests to rule out celiac disease. Anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody was negative, and the patient was positive for HLA-DQ5 and DQ6, which made the possibility of underlying celiac disease less likely. A test for food allergies was also unremarkable.

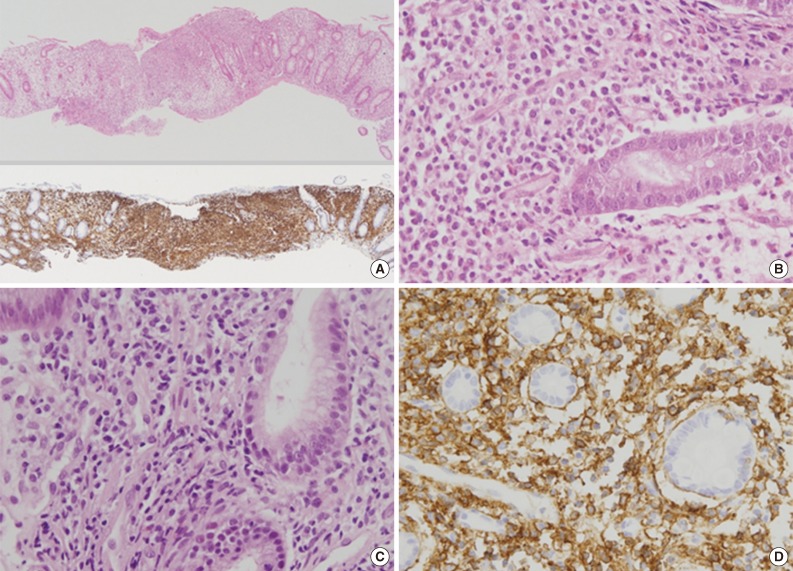

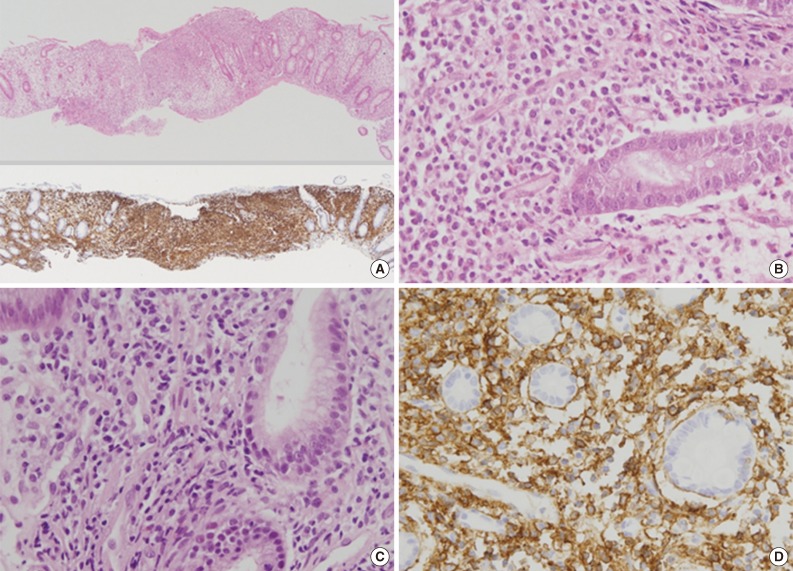

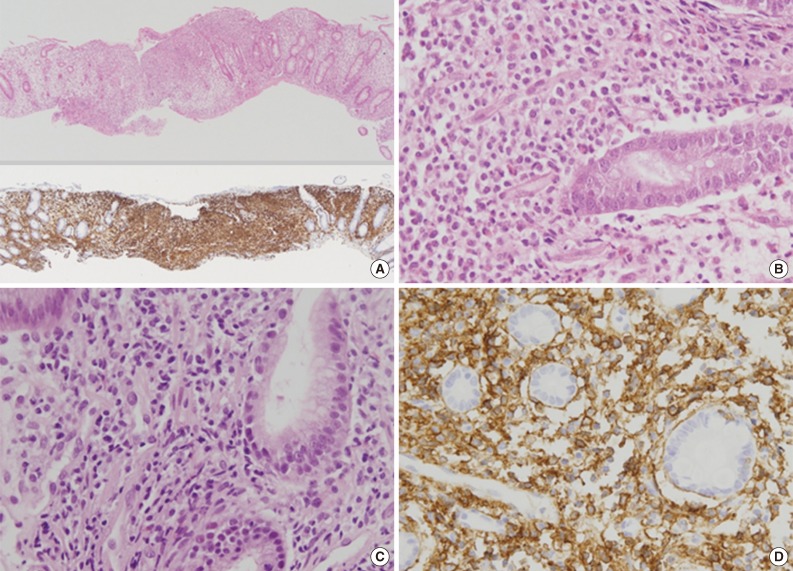

- Multiple endoscopic biopsies were taken from the esophagus to the colon, which all exhibited similar histological features. The lamina propria was expanded by infiltration of atypical monomorphic lymphoid cells. The infiltrate was vaguely demarcated from the adjacent relatively unaffected mucosa in the colon. The atypical lymphoid cells were medium-sized with slightly irregular nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli and finely clumped chromatin. They had a moderate amount of pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 2). Mitotic figures were occasionally observed. Necrosis, apoptosis, and angiocentricity were absent. Some scattered eosinophils were noted in the lamina propria. Enteropathy features including villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and intraepithelial lymphocytosis were not observed. On immunohistochemistry, the lymphoid cells were positive for cytoplasmic CD3, CD56, CD8, and T-cell-restricted intracellular antigen-1, and negative for CD4, CD20, and TCRβF1 (clone 8A3, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) (Fig. 2). This immunophenotype suggested an NK-cell or γδ T-cell origin. The proliferation rate as determined by Ki-67 was low, up to 19.8%. EBV was not detected by in situ hybridization using an EBV-encoded RNA 1/2 probe. Molecular analysis for TCRγ gene rearrangement using BIOMED-2 multiplex PCR for TCRGA: VγI/γ10-Jγ; TCRGB: Vγ9/γ11-Jγ (InVivo-Scribe Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA) on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue showed no evidence of T-cell monoclonality. Later immunohistochemistry for TCRG (1:20, γ3.20, Endogen, Rockford, IL, USA) was carried out, which was negative.

- Despite a presumptive pathologic diagnosis of intestinal γδT-cell or NK-cell lymphoma, no chemotherapy was administered due to low clinical suspicion of malignancy and the poor nutritional status of the patient. He instead has been closely followed with regular clinical evaluation. Gastroduodenoscopy six months later demonstrated persistent mucosal nodularity in the duodenum, but biopsy revealed mild lymphoplasma cell infiltration with only a few scattered CD3(+) cells and no CD56(+) cells. The patient's symptoms and LDH level waxed and waned, while anemia and hypoalbuminemia have been persistent. However, 40 months later, GI symptoms were aggravated and multifocal ulcerations were observed in colon and stomach. The result of endoscopic biopsy proved recurrence of disease.

CASE REPORT

- In the present patient, an unusual infiltration of monomorphic cytoplasmic CD3(+), CD56(+), TCRβF1(-) cells in GI tract led us to consider extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma or γδT-cell lymphomas. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma occasionally presents with primary GI lymphoma and can have broad cytomorphologic features. However, tumor cells are infected with EBV in virtually all cases, and have irregularly-folded or elongated nuclei with dark chromatin. They frequently exhibit angiocentric and angiodestructive growth patterns with necrosis and apoptosis.1 The cytomorphology and histology of the present case and the absence of EBV varied widely from extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma.

- Current World Health Organization (WHO) classification includes two types of γδT-cell lymphoma, hepatosplenic γδT-cell lymphoma and primary cutaneous γδT-cell lymphoma.1 Although γδT-cells constitute only 1% to 5% of the lymphocytes in peripheral blood, they account for up to 50% of T-cells in the skin and intestine. In fact, intestinal lymphoma derived from γδT-cells has been well described in type II EATL.1,5-7 Type I EATL in its classical form is predominantly encountered in Western countries, and has a strong association with celiac disease and HLA-DQ2 or DQ8 expression. Usually the tumor cells are medium to large, often display a pleomorphic appearance in an inflammatory background, and typically have CD3(+), CD4(-), CD8(-), and CD56(-) immunophenotypes. On the other hand, type II EATL, or monomorphic variant EATL, is commonly found in Asian populations and has less association with celiac disease. It is characteristically composed of monomorphic small- to medium-sized cells, which frequently exhibit CD3(+), CD4(-), CD8(+), and CD56(+) phenotypes.1,5,7,8 Recently mounting evidences has demonstrated that type II EATL commonly expresses γδTCR, unlike type I EATL, and therefore might be a distinct form of intestinal lymphoma originating from γδT-cells.6,7 Nevertheless, both type I and II EATL are aggressive diseases and still share some clinicopathologic characteristics including enteropathy features such as villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and intraepithelial lymphocytosis.1,5,8 The immunophenotype of infiltrated cells in the present patient overlaps with EATL, especially type II EATL; however, our patient had no evidence of celiac disease. Moreover, neither histological features suggestive of enteropathy nor T-cell monoclonality were observed. Most importantly, the indolent chronic clinical course of the present case was not compatible with EATL or any other type of intestinal NK- or T-cell lymphoma.

- To the best of our knowledge, this case is most closely akin to a unique entity recently described as "NK-cell enteropathy" or "lymphomatoid gastropathy" by Western and Japanese researchers.3,4 This disorder is pathologically characterized by an infiltration of atypical cytoplasmic CD3(+), CD56(+), CD4(-), CD8(-), TCR(-), cytotoxic molecule(+) lymphoid cells into the lamina propria of the GI tract from stomach to colon. Cytomorphologically, cells were medium to large with a moderate amount of clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm. The NK-cell nature of cells was also demonstrated by flow cytometric analysis in a subset of the patients. T-cell monoclonality or typical enteropathic features have not been observed. Despite the worrisome monomorphic CD56(+) lymphoid cell infiltration mimicking intestinal NK- or T-cell lymphoma, all patients experienced a benign or indolent course without disease progression. They were alive with persistent disease or the lesions were self-regressed with only occasional relapses.

- The pathologic features of this entity are quite similar to those of our patient except for CD8 expression. Normal NK-cells show variable expression of CD8 in addition to the subunits of the CD3 complex including the ε and ζ chains.9 Considering this, the expression of CD8 seen in our patient would be plausible, and may not conflict with a diagnosis of "NK-cell enteropathy." The possibility of a γδT-cell origin of infiltrating cells was lower considering the absence of TCRG expression by immunohistochemistry. Moreover, no instances of non-neoplastic infiltration of polyclonal γδT-cells have been reported previously.

- Previous cases described as "NK-cell enteropathy" or "lymphomatoid gastropathy" occurred only in adults. The etiology and the pathogenesis of this unique lesion remain speculative. The clinical course of patients is suggestive of a non-neoplastic inflammatory process rather than a neoplastic process.3,4 Transient increase of circulating NK-cells has been observed in autoimmune disorders and viral infections. NK-cells are also found in the lamina propria of the intestine and involved in mucosal immunity in order to control infections or immune responses.10 The cause of abnormal NK-cell infiltration in the GI tract, if the proliferating NK-cells are monoclonal versus polyclonal, and the long-term course of patients still remain to be elucidated. Our patient is thought to be the first example of childhood or adolescent onset of this disorder, which might explain the unusual clinical manifestation, including failure to thrive. The patient's symptoms were persistent with late recurrence, which might suggest an indolent but possibly chronic course of the disease. An otherwise unknown immunologic or inflammatory process underling the atypical NK-cell proliferation might explain the lingering symptoms of our patient.

- In summary, we reported an adolescent case of "NK-cell enteropathy" demonstrating multiple mucosal involvement of the GI tract. "NK-cell enteropathy" is regarded as a distinctive clinicopathologic entity which should be observed closely, while aggressive chemotherapy should be avoided. Because of its similarity to intestinal CD56(+) T- or NK-cell lymphoma, it is important to carefully and accurately diagnose this entity to prevent misinterpretation of the biopsy and potentially harmful consequences for the patients in clinical practice.

DISCUSSION

- 1. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC Press, 2008.

- 2. Kim JM, Ko YH, Lee SS, et al. WHO classification of malignant lymphomas in Korea: report of the third nationwide study. Korean J Pathol 2011; 45: 254-260. Article

- 3. Mansoor A, Pittaluga S, Beck PL, Wilson WH, Ferry JA, Jaffe ES. NK-cell enteropathy: a benign NK-cell lymphoproliferative disease mimicking intestinal lymphoma: clinicopathologic features and follow-up in a unique case series. Blood 2011; 117: 1447-1452. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 4. Takeuchi K, Yokoyama M, Ishizawa S, et al. Lymphomatoid gastropathy: a distinct clinicopathologic entity of self-limited pseudomalignant NK-cell proliferation. Blood 2010; 116: 5631-5637. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 5. Tse E, Gill H, Loong F, et al. Type II enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: a multicenter analysis from the Asia Lymphoma Study Group. Am J Hematol 2012; 87: 663-668. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Garcia-Herrera A, Song JY, Chuang SS, et al. Nonhepatosplenic gammadelta T-cell lymphomas represent a spectrum of aggressive cytotoxic T-cell lymphomas with a mainly extranodal presentation. Am J Surg Pathol 2011; 35: 1214-1225. PubMedPMC

- 7. Chan JK, Chan AC, Cheuk W, et al. Type II enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: a distinct aggressive lymphoma with frequent gammadelta T-cell receptor expression. Am J Surg Pathol 2011; 35: 1557-1569. PubMed

- 8. Delabie J, Holte H, Vose JM, et al. Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: clinical and histological findings from the international peripheral T-cell lymphoma project. Blood 2011; 118: 148-155. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 9. Morice WG. The immunophenotypic attributes of NK cells and NK-cell lineage lymphoproliferative disorders. Am J Clin Pathol 2007; 127: 881-886. ArticlePubMed

- 10. Shi FD, Ljunggren HG, La Cava A, Van Kaer L. Organ-specific features of natural killer cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11: 658-671. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

REFERENCES

Fig. 1Endoscopic findings of the patient. Representative images from the stomach (A) and IC valve (B). Both lesions show mucosal nodularity or elevation with hyperemic change.

Fig. 2Pathologic findings of colon and stomach lesions. Representative images from the colon (A, B) and stomach (C, D). (A, upper) Lamina propria of the colonic mucosa is infiltrated by atypical lymphoid cells, which resulted in separation of crypts. (A, lower) The atypical cells are diffusely positive for CD56 by immunohistochemistry. (B) The atypical lymphoid cells are monomorphic, medium to large in size, and have irregular nuclei and a moderate amount of clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm. (C) The lamina propria of the gastric mucosa is also infiltrated by atypical lymphoid cells, which are also strongly positive for CD56 (D).

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- Indolent T- and Natural Killer-Cell Lymphomas and Lymphoproliferative Diseases—Entities in Evolution

Chi Sing Ng

Lymphatics.2025; 3(4): 41. CrossRef - Indolent T-Cell/Natural Killer-Cell Lymphomas/Lymphoproliferative Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract—What Have We Learned in the Last Decade?

Xin-Gen Wang, Wei-Hua Yin, Huan-You Wang

Laboratory Investigation.2024; 104(4): 102028. CrossRef - A case of excisionally remitted indolent NK‐cell enteropathy in the oral cavity and a mini‐review

Xiangyun Li, Zhu Li, Xiaoge Zhou, Yuanyuan Zheng, Yanlin Zhang, Jianlan Xie

Journal of Cutaneous Pathology.2024; 51(7): 518. CrossRef - Clinicopathological and molecular features of indolent natural killer‐cell lymphoproliferative disorder of the gastrointestinal tract

Hongmei Yi, Anqi Li, Binshen Ouyang, Qian Da, Lei Dong, Yingting Liu, Haimin Xu, Xiaoyun Zhang, Wei Zhang, Xiaofen Jin, Yijin Gu, Yan Wang, Zebing Liu, Chaofu Wang

Histopathology.2023; 82(4): 567. CrossRef - Indolent T- and NK-Cell Lymphoproliferative Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract: Current Understanding and Outstanding Questions

Craig R. Soderquist, Govind Bhagat

Hemato.2022; 3(1): 219. CrossRef - Lymphomatoid gastropathy/NK-cell enteropathy involving the stomach and intestine

Makoto Nakajima, Masayuki Shimoda, Kengo Takeuchi, Akito Dobashi, Takanori Kanai, Yae Kanai, Yasushi Iwao

Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hematopathology.2022; 62(2): 114. CrossRef - Cellular Origins and Pathogenesis of Gastrointestinal NK- and T-Cell Lymphoproliferative Disorders

Susan Swee-Shan Hue, Siok-Bian Ng, Shi Wang, Soo-Yong Tan

Cancers.2022; 14(10): 2483. CrossRef - Lymph node involvement by enteropathy-like indolent NK-cell proliferation

Jean-Louis Dargent, Nicolas Tinton, Mounir Trimech, Laurence de Leval

Virchows Archiv.2021; 478(6): 1197. CrossRef - Diagnostic approach to T- and NK-cell lymphoproliferative disorders in the gastrointestinal tract

Swee-Shan Hue Susan, Siok-Bian Ng, Shi Wang, Soo-Yong Tan

Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology.2021; 38(4): 21. CrossRef - Natural Killer-cell Enteropathy of the Stomach in an Elderly Woman: A Case Report

Ye young Koo, Jin Lee, Bomi Kim, Su Jin Jeong, Eun Hye Oh, Yong Eun Park, Jongha Park, Tae Oh Kim

The Korean Journal of Gastroenterology.2021; 78(6): 349. CrossRef - Gastrointestinal T- and NK-cell lymphomas and indolent lymphoproliferative disorders

Craig R. Soderquist, Govind Bhagat

Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology.2020; 37(1): 11. CrossRef - T- and NK-cell lymphoproliferative disorders of the gastrointestinal tract: review and update

Chris van Vliet, Dominic V. Spagnolo

Pathology.2020; 52(1): 128. CrossRef - An Enteropathy-like Indolent NK-Cell Proliferation Presenting in the Female Genital Tract

Rahul Krishnan, Kari Ring, Eli Williams, Craig Portell, Elaine S. Jaffe, Alejandro A. Gru

American Journal of Surgical Pathology.2020; 44(4): 561. CrossRef - NK-cell enteropathy, a potential diagnostic pitfall of intestinal lymphoproliferative disease

Runjin Wang, Sanjay Kariappa, Christopher W. Toon, Winny Varikatt

Pathology.2019; 51(3): 338. CrossRef - Indolent T cell lymphoproliferative disorder with villous atrophy in small intestine diagnosed by single-balloon enteroscopy

Takashi Nagaishi, Daiki Yamada, Kohei Suzuki, Ryosuke Fukuyo, Eiko Saito, Masayoshi Fukuda, Taro Watabe, Naoya Tsugawa, Kengo Takeuchi, Kouhei Yamamoto, Ayako Arai, Kazuo Ohtsuka, Mamoru Watanabe

Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology.2019; 12(5): 434. CrossRef - NK-Cell Enteropathy and Similar Indolent Lymphoproliferative Disorders

Daniel Xia, Elizabeth A Morgan, David Berger, Geraldine S Pinkus, Judith A Ferry, Lawrence R Zukerberg

American Journal of Clinical Pathology.2018;[Epub] CrossRef - Clinicopathological categorization of Epstein–Barr virus-positive T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative disease: an analysis of 42 cases with an emphasis on prognostic implications

Jin Ho Paik, Ji-Young Choe, Hyojin Kim, Jeong-Ok Lee, Hyoung Jin Kang, Hee Young Shin, Dong Soon Lee, Dae Seog Heo, Chul-Woo Kim, Kwang-Hyun Cho, Tae Min Kim, Yoon Kyung Jeon

Leukemia & Lymphoma.2017; 58(1): 53. CrossRef - Indolent T‐ and NK‐cell lymphoproliferative disorders of the gastrointestinal tract: a review and update

Rahul Matnani, Karthik A. Ganapathi, Suzanne K. Lewis, Peter H. Green, Bachir Alobeid, Govind Bhagat

Hematological Oncology.2017; 35(1): 3. CrossRef - Indolent NK cell proliferative lesion mimicking NK/T cell lymphoma in the gallbladder

Su Hyun Hwang, Joon Seong Park, Seong Hyun Jeong, Hyunee Yim, Jae Ho Han

Human Pathology: Case Reports.2016; 5: 39. CrossRef - Recent advances in intestinal lymphomas

Periklis G Foukas, Laurence de Leval

Histopathology.2015; 66(1): 112. CrossRef

Benign Indolent CD56-Positive NK-Cell Lymphoproliferative Lesion Involving Gastrointestinal Tract in an Adolescent

Fig. 1 Endoscopic findings of the patient. Representative images from the stomach (A) and IC valve (B). Both lesions show mucosal nodularity or elevation with hyperemic change.

Fig. 2 Pathologic findings of colon and stomach lesions. Representative images from the colon (A, B) and stomach (C, D). (A, upper) Lamina propria of the colonic mucosa is infiltrated by atypical lymphoid cells, which resulted in separation of crypts. (A, lower) The atypical cells are diffusely positive for CD56 by immunohistochemistry. (B) The atypical lymphoid cells are monomorphic, medium to large in size, and have irregular nuclei and a moderate amount of clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm. (C) The lamina propria of the gastric mucosa is also infiltrated by atypical lymphoid cells, which are also strongly positive for CD56 (D).

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Benign Indolent CD56-Positive NK-Cell Lymphoproliferative Lesion Involving Gastrointestinal Tract in an Adolescent

E-submission

E-submission

PubReader

PubReader Cite this Article

Cite this Article