Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Pathol Transl Med > Volume 60(1); 2026 > Article

-

Original Article

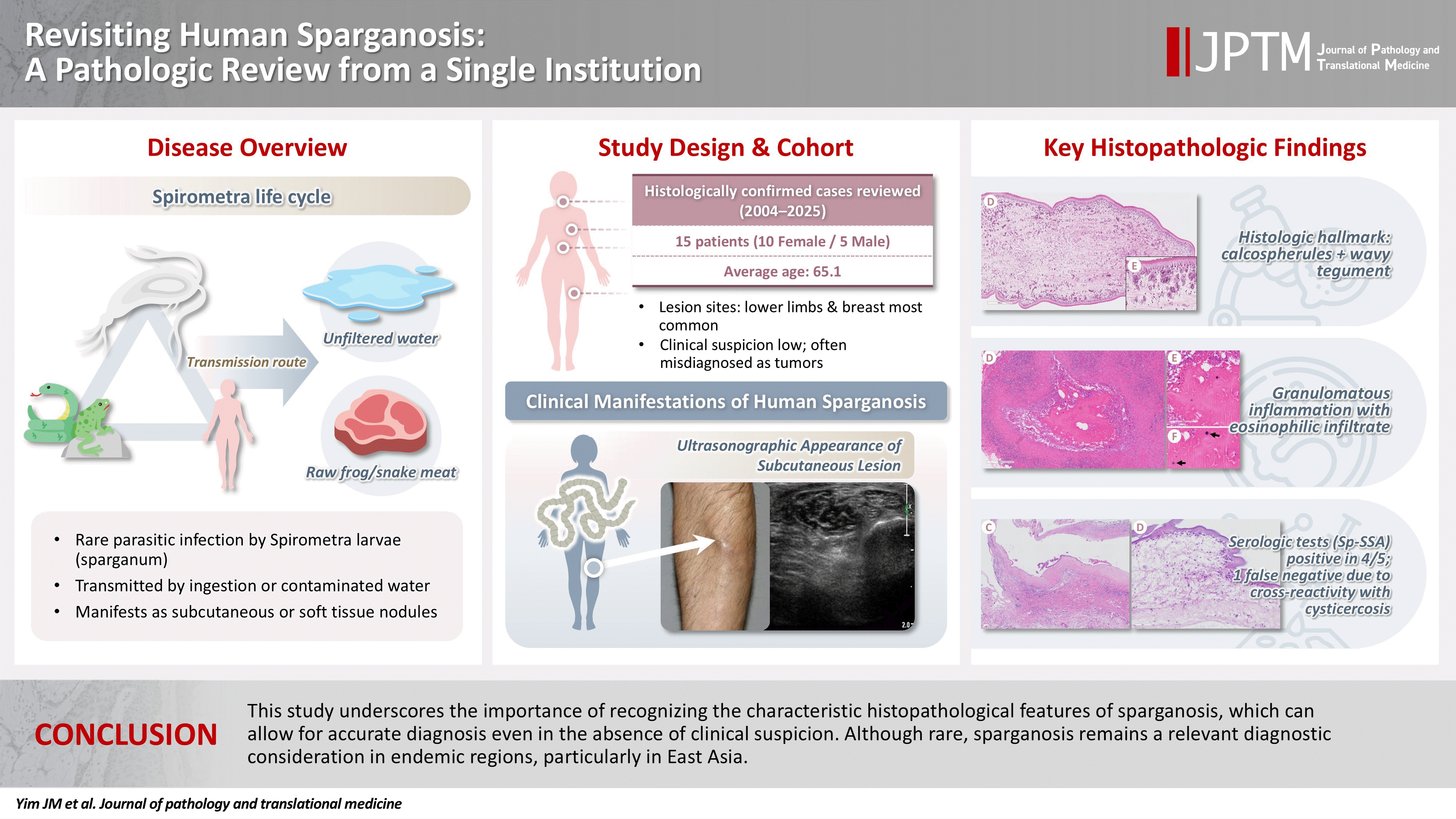

Revisiting human sparganosis: a pathologic review from a single institution -

Jeemin Yim1

, Young A Kim1

, Young A Kim1 , Jeong Hwan Park1

, Jeong Hwan Park1 , Hye Eun Park1

, Hye Eun Park1 , Hyun Beom Song2

, Hyun Beom Song2 , Ji Eun Kim1

, Ji Eun Kim1

-

Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine 2026;60(1):83-91.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2025.10.14

Published online: January 9, 2026

1Department of Pathology, Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

2Department of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology, Institute of Endemic Diseases, Seoul National University Medical Research Center, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- Corresponding Author: Ji Eun Kim, MD, PhD Department of Pathology, Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 20 Boramae-ro 5-gil, Dongjak-gu, Seoul 07061, Korea Tel: +82-2-870-2642, Fax: +82-2-831-0261, E-mail: npol181@snu.ac.kr

© The Korean Society of Pathologists/The Korean Society for Cytopathology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,484 Views

- 81 Download

Abstract

-

Background

- Sparganosis is a rare parasitic infection caused by Spirometra species. Although it was relatively common in the past, it is now often overlooked. In this study, we review cases diagnosed through histopathological examination at a single institution in recent years to raise awareness of this neglected parasitic disease.

-

Methods

- We retrospectively analyzed cases of human sparganosis identified in the pathology archives of a single institution in South Korea between 2004 and 2025. A comprehensive review was conducted, including demographic data, clinical features, lesion locations, imaging findings, exposure history (such as dietary habits), and histopathologic findings.

-

Results

- A total of 15 patients were identified, including 10 females and 5 males, with a mean age of 65.1 years. Lesions were most commonly located in the lower extremities and breast. Imaging findings were largely nonspecific, with ultrasonography being the most frequently used modality. In most cases, clinical suspicion of sparganosis was absent, and excision was performed under the impression of a benign or malignant tumor. Histologically, variably degenerated parasitic structures were identified within granulomatous inflammation. However, preserved features such as calcospherules and tegumental structures facilitated definitive diagnosis.

-

Conclusions

- This study underscores the importance of recognizing the characteristic histopathological features of sparganosis, which can allow for accurate diagnosis even in the absence of clinical suspicion. Although rare, sparganosis remains a relevant diagnostic consideration in endemic regions, particularly in East Asia.

- Sparganosis is a rare parasitic infection in humans caused by the plerocercoid larvae (spargana) of Spirometra species, a genus of pseudophyllidean tapeworms [1]. Human infection typically occurs accidentally through the consumption of raw or undercooked amphibians or reptiles, or via drinking water contaminated with procercoid-infected copepods [1]. The life cycle of Spirometra involves multiple hosts, with humans serving as secondary or paratenic hosts.

- Clinically, sparganosis most commonly presents as a slowly migrating subcutaneous nodule, which may be asymptomatic or mildly tender [2]. Depending on the site of invasion, spargana can involve the orbit, central nervous system, genitourinary tract, or visceral organs, sometimes resulting in significant symptoms. Radiologic studies may provide clues such as calcifications, tubular structures, or peritubular changes; however, these findings are usually nonspecific and rarely diagnostic [3-6]. Consequently, diagnosis is often made histopathologically following surgical excision, frequently in the absence of prior clinical suspicion. This makes diagnosis especially challenging for pathologists unfamiliar with its characteristic features.

- Although rare globally, sparganosis is reported more frequently in East and Southeast Asia, particularly in Korea, China, Japan, and Thailand. In Korea, over 400 cases have been reported in the literature [7-13], although incidence has declined in recent years, likely due to improvements in public health and hygiene. Nevertheless, sporadic cases continue to be encountered.

- Most literature consists of case reports or studies of uncommon anatomical involvement, while comprehensive analyses within defined populations remain limited. In this study, we present a case series of 15 histologically confirmed cases of human sparganosis diagnosed at a single institution in Korea over a 21-year period. This study aims to provide practical diagnostic insights for pathologists and to raise awareness of this neglected parasitic infection.

INTRODUCTION

- A total of 15 cases of human sparganosis diagnosed at Seoul Metropolitan Government-Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center between 2004 and 2025 were included in this study. Two cases previously published as a case report [10] were also included to provide a comprehensive institutional review. Clinical data, imaging findings, exposure history (drinking of unfiltered water or ingestion of raw frog/snakes), and histopathological features were retrospectively reviewed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

- Clinical and demographic features

- Table 1 summarizes the clinical and histopathologic characteristics of the 15 patients. The cohort comprised 10 women and 5 men, with a mean age of 65.1 years (range, 46 to 83 years). All patients were Korean nationals except for one Chinese individual. Only two patients (13.3%) reported a history of consuming raw snake or frog meat. The remaining patients denied known exposures and were unable to recall any relevant risk factors. Serological testing for sparganum-specific antibody was performed in five patients, of whom four showed positive results (Table 1). In one spinal cord case, however, the sparganum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was negative while the cysticercosis antibody was slightly elevated, although histopathology confirmed sparganosis.

- Anatomic distribution and imaging characteristics

- Lesions were located predominantly in the subcutaneous tissue, most frequently in the lower extremities (n = 6) and breast (n = 4), followed by the trunk (n = 2), neck (n = 1), and pubic region (n = 1). One case involved the spinal canal, and none involved visceral organs. In most cases, sparganosis was not clinically suspected; lesions were often interpreted as benign tumors, lymphadenopathy, or mesenchymal neoplasms. Ultrasonography was the most commonly used imaging modality, typically revealing nonspecific hypoechoic or tubular structures.

- Summary of clinicopathologic findings in representative cases

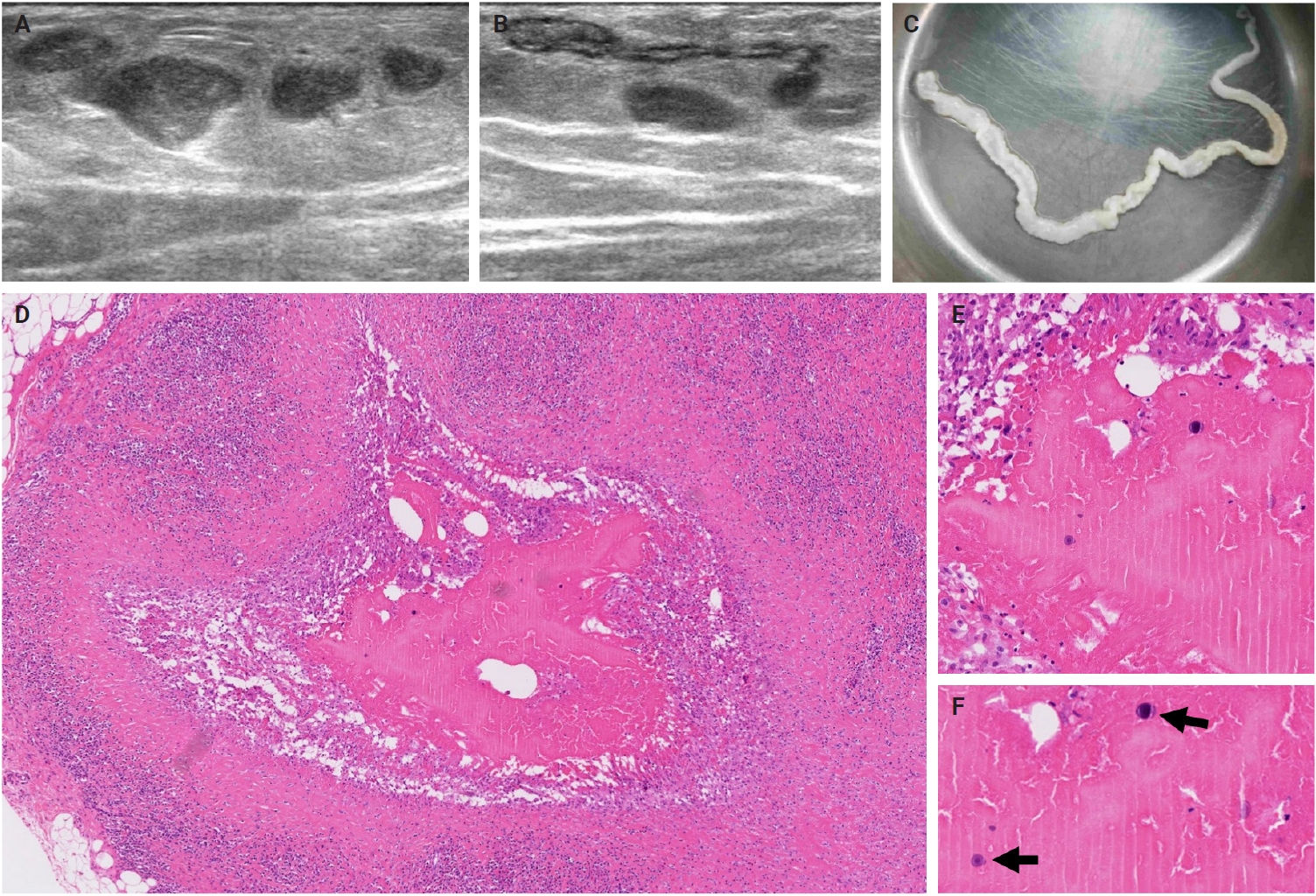

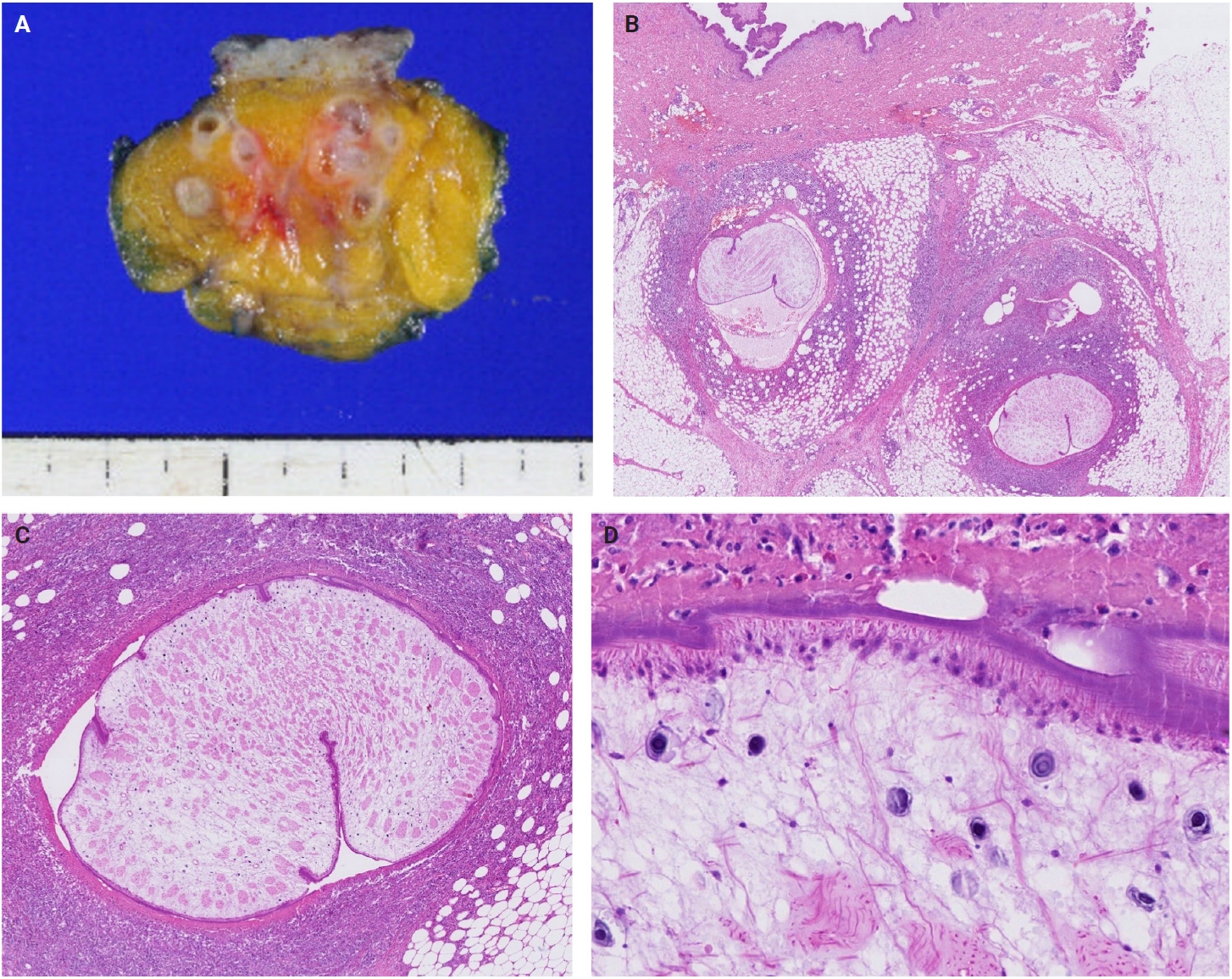

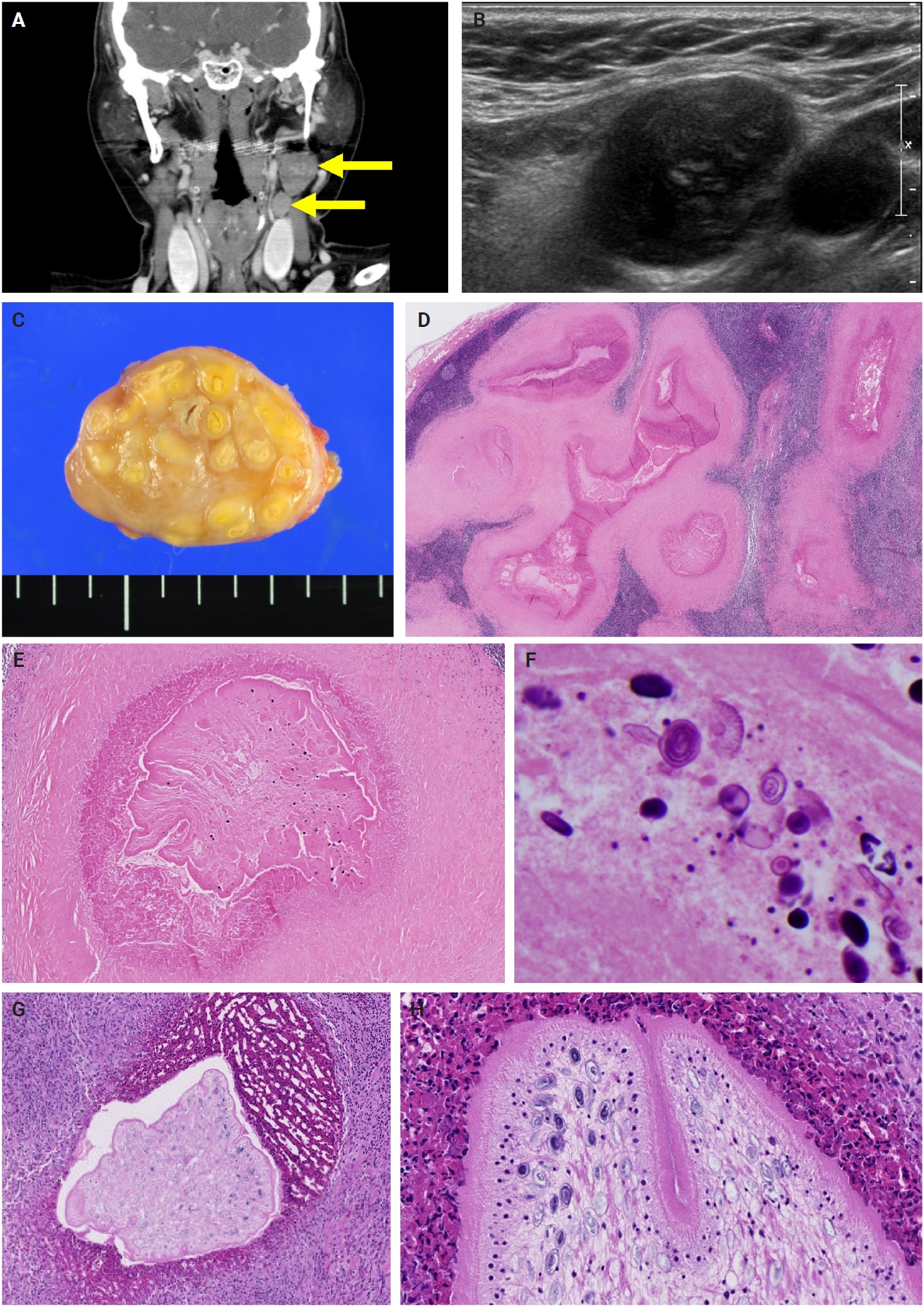

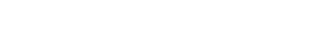

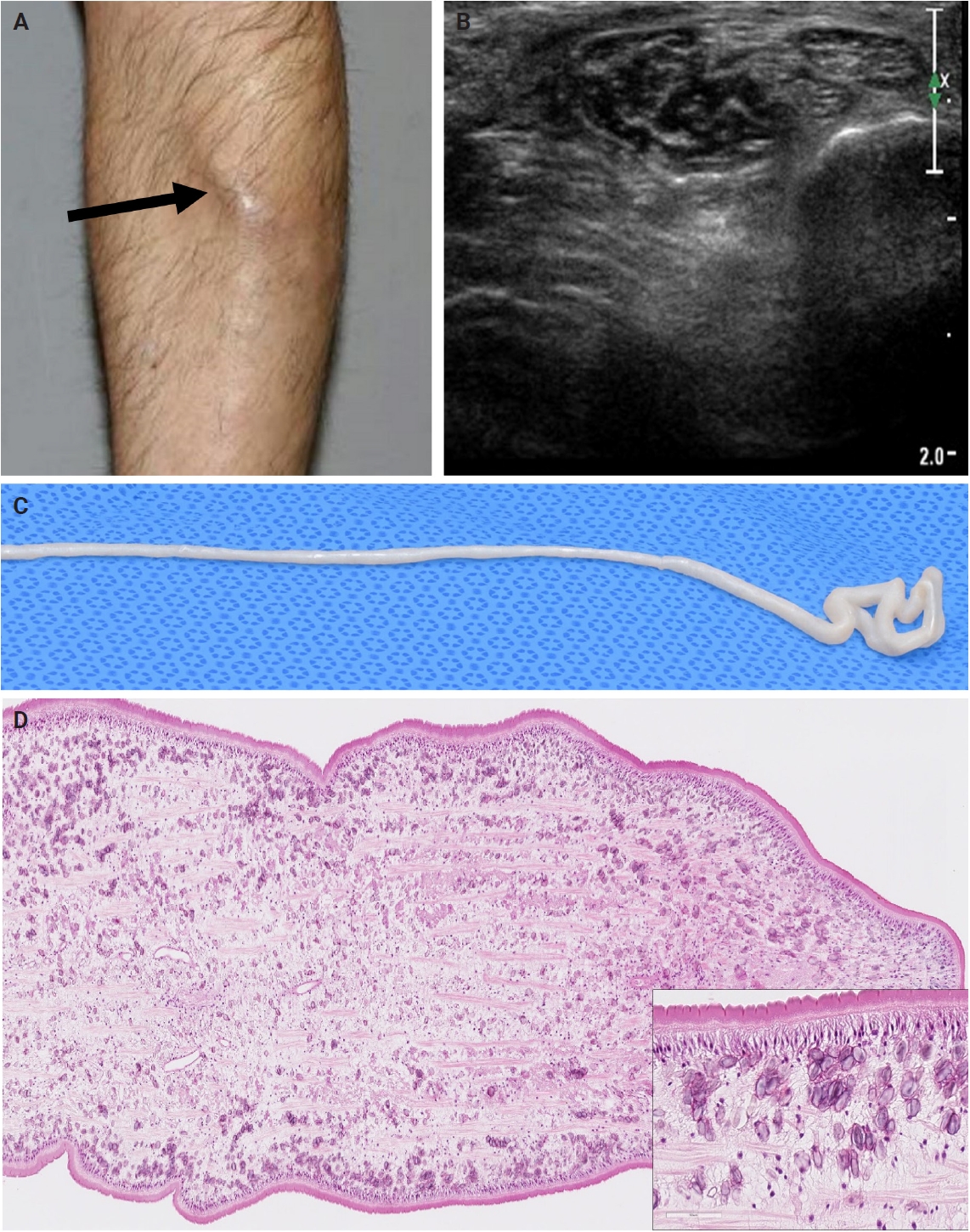

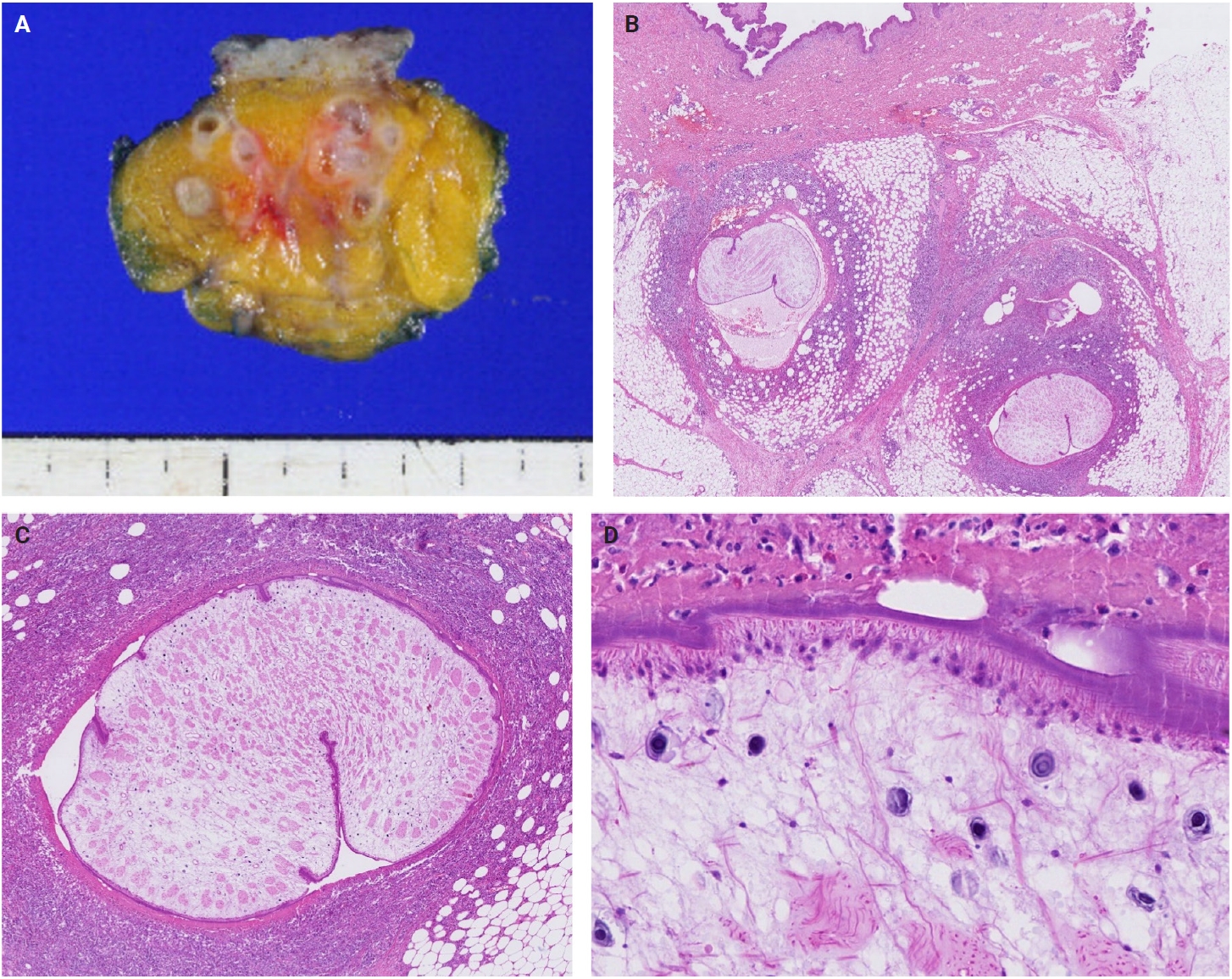

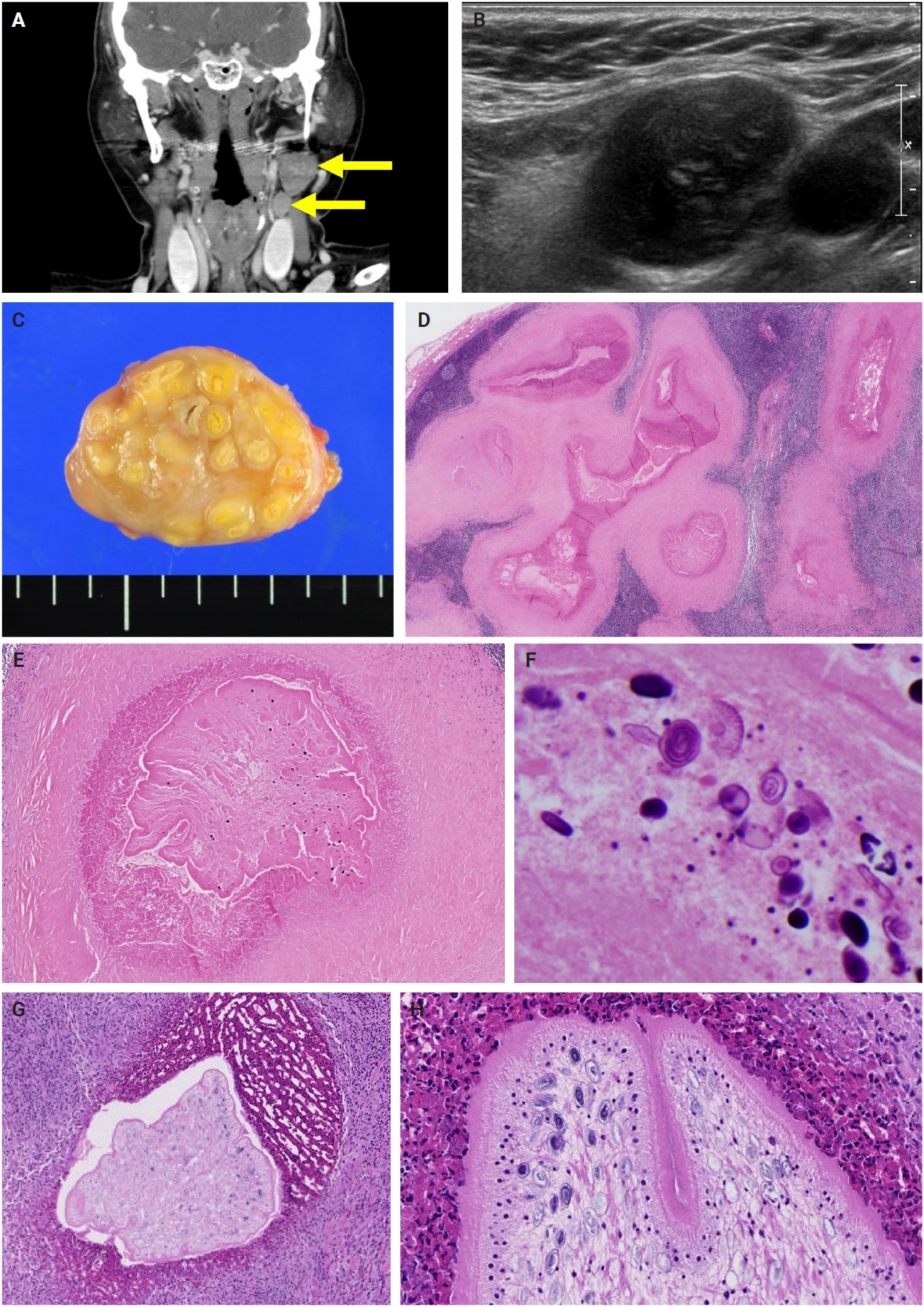

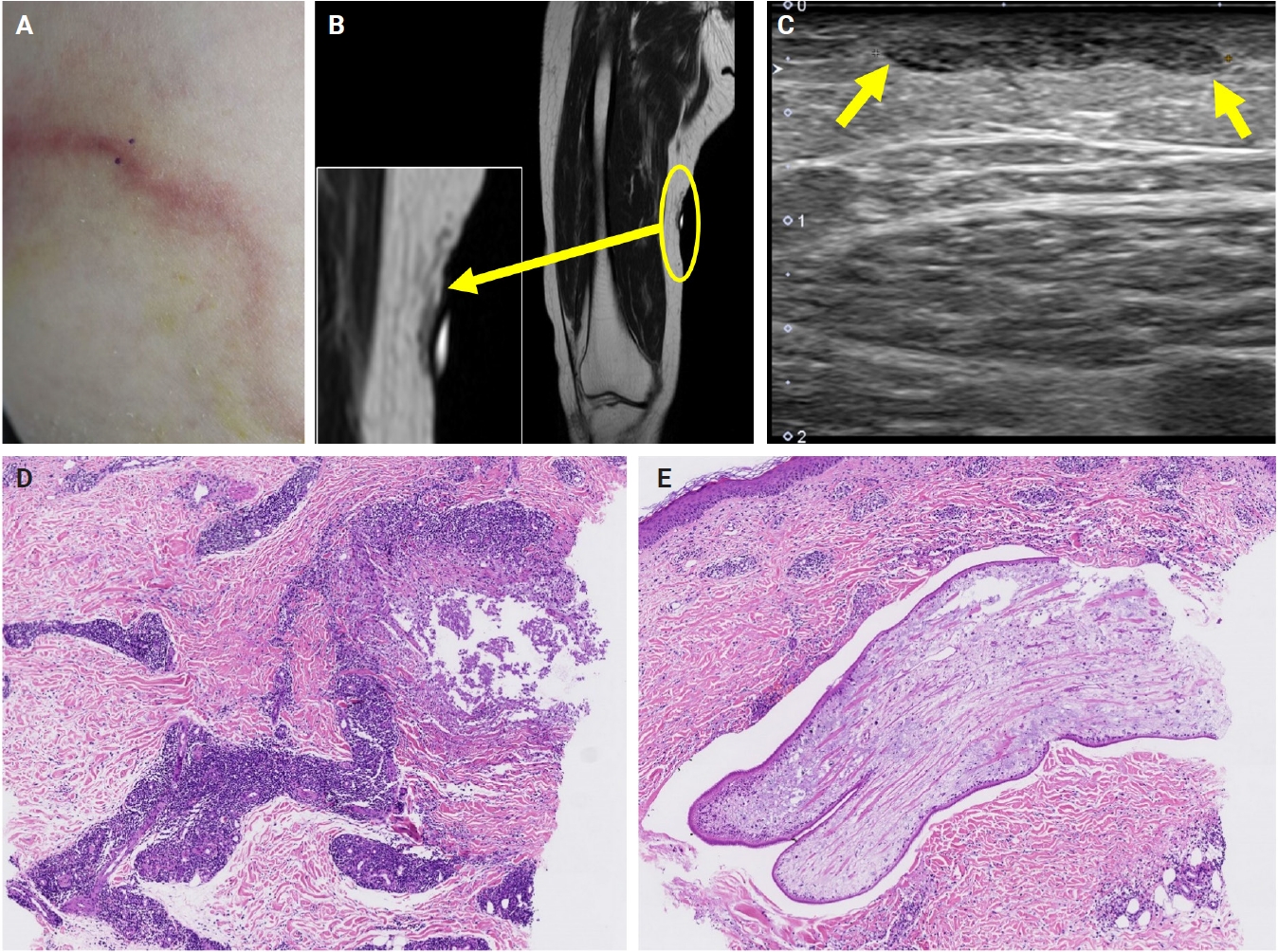

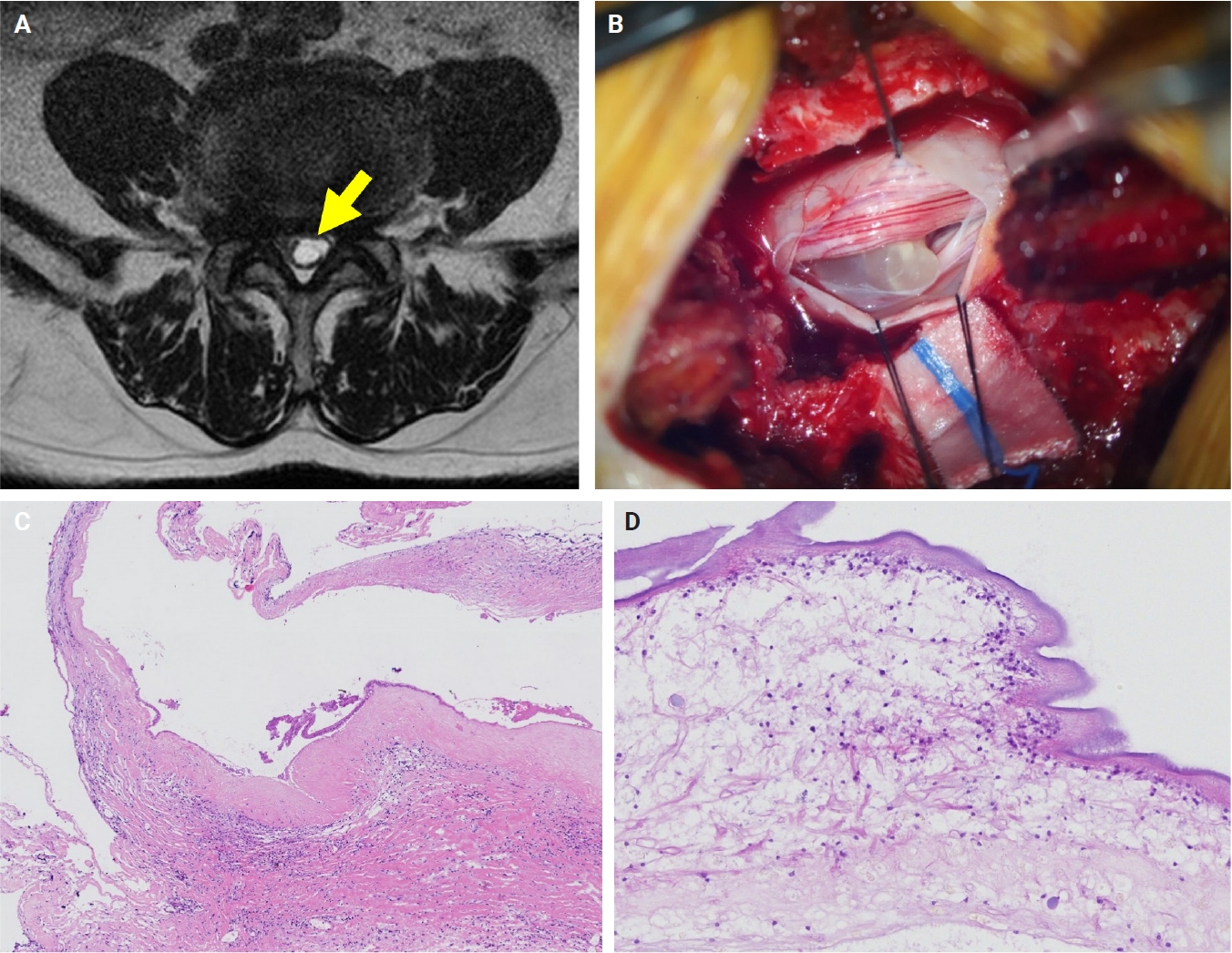

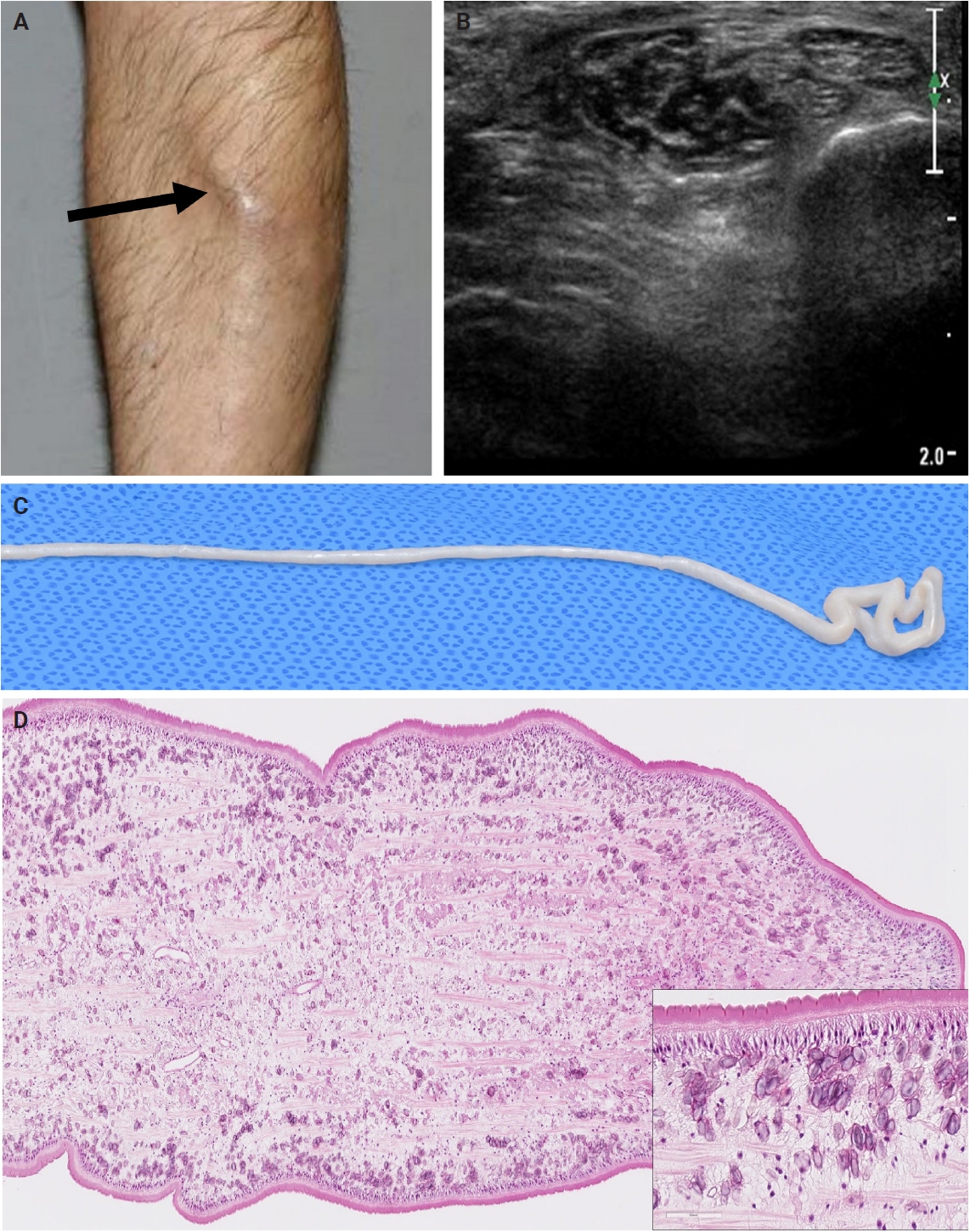

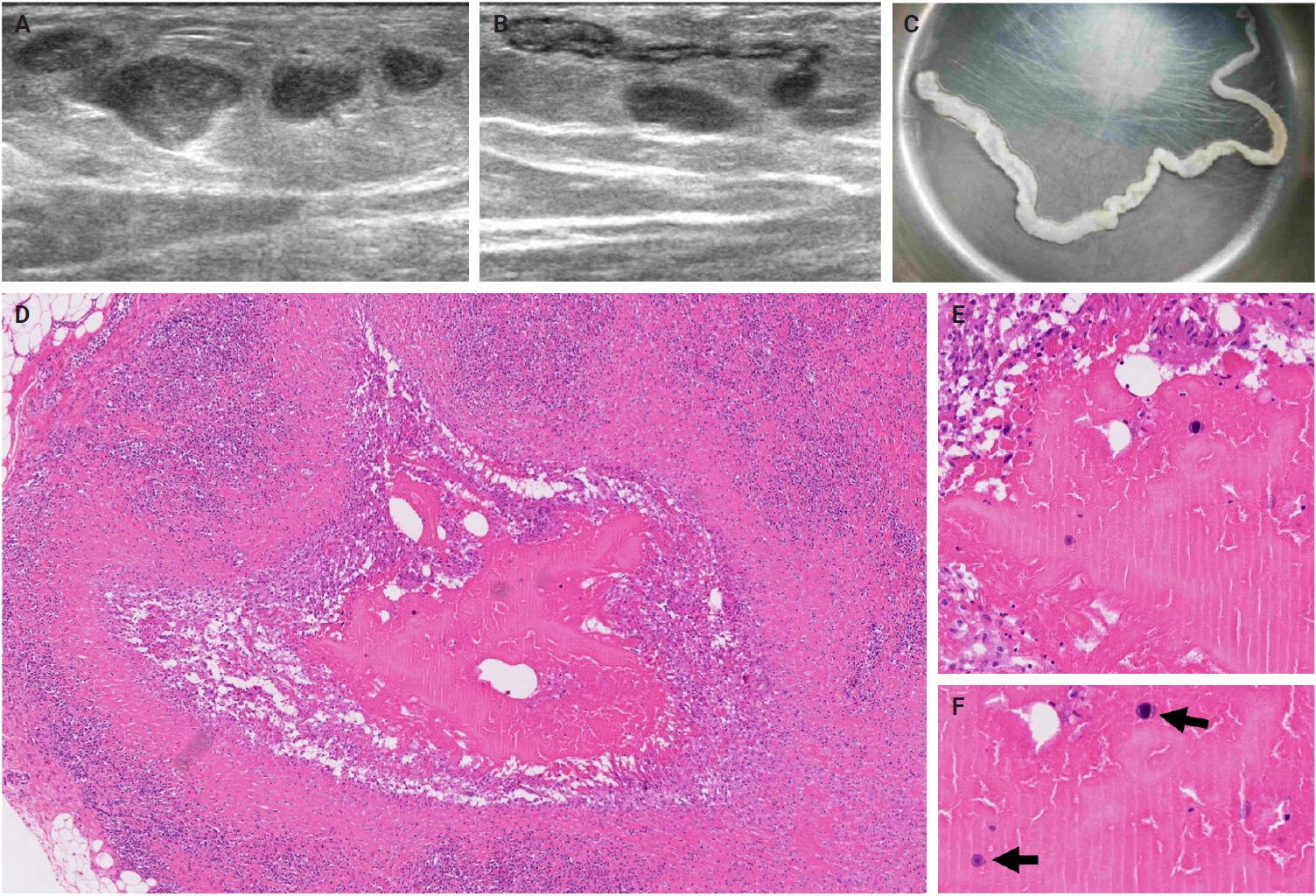

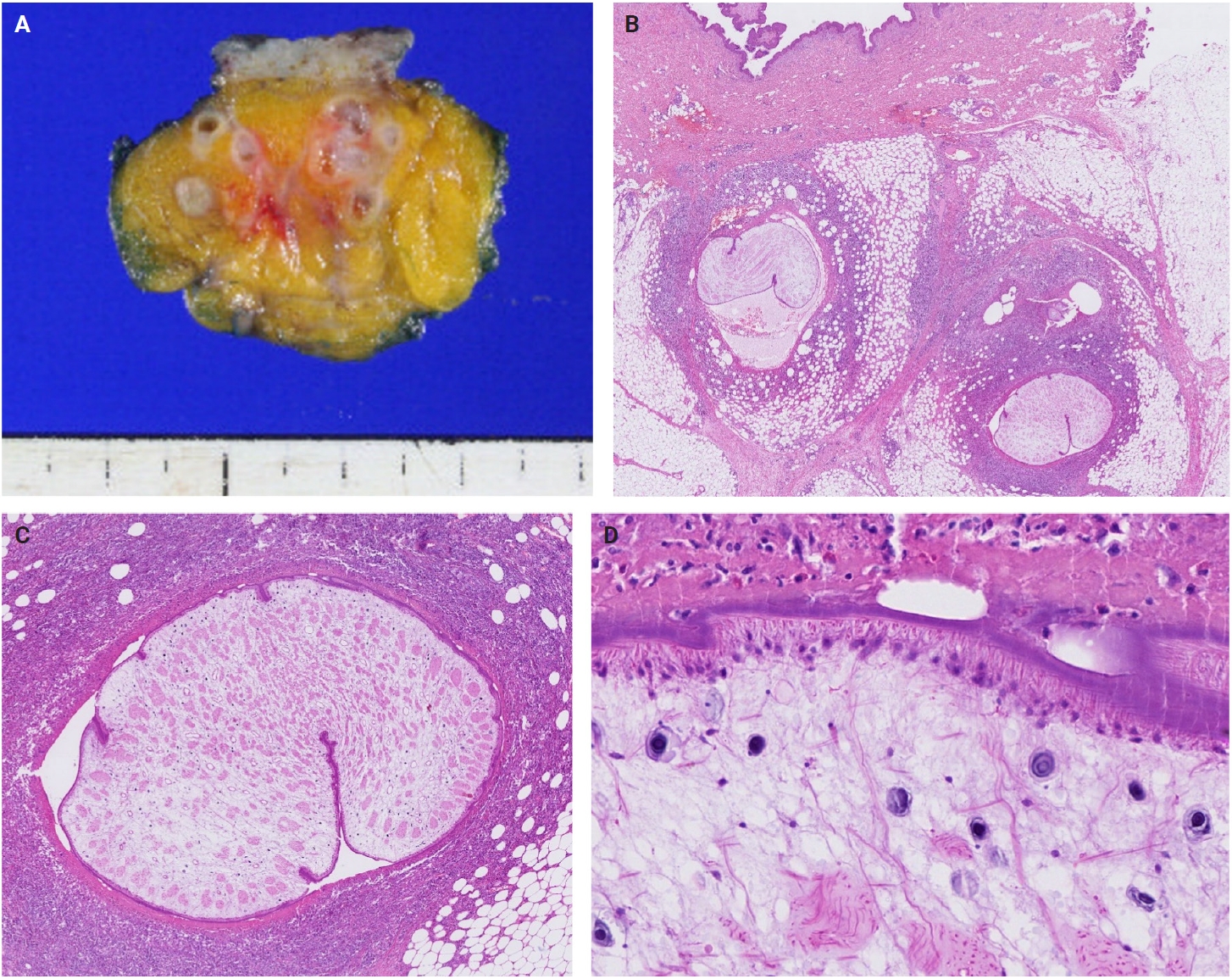

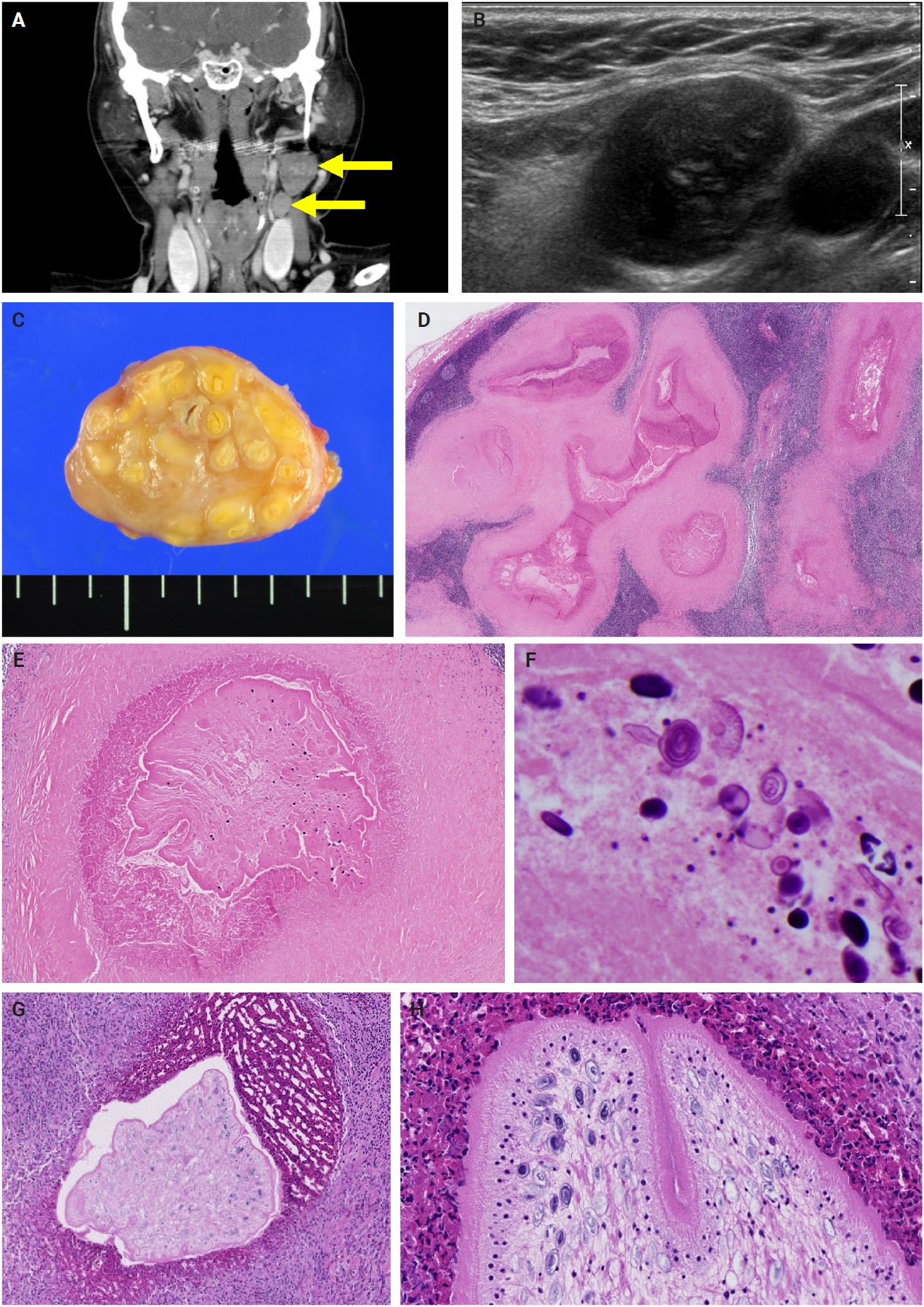

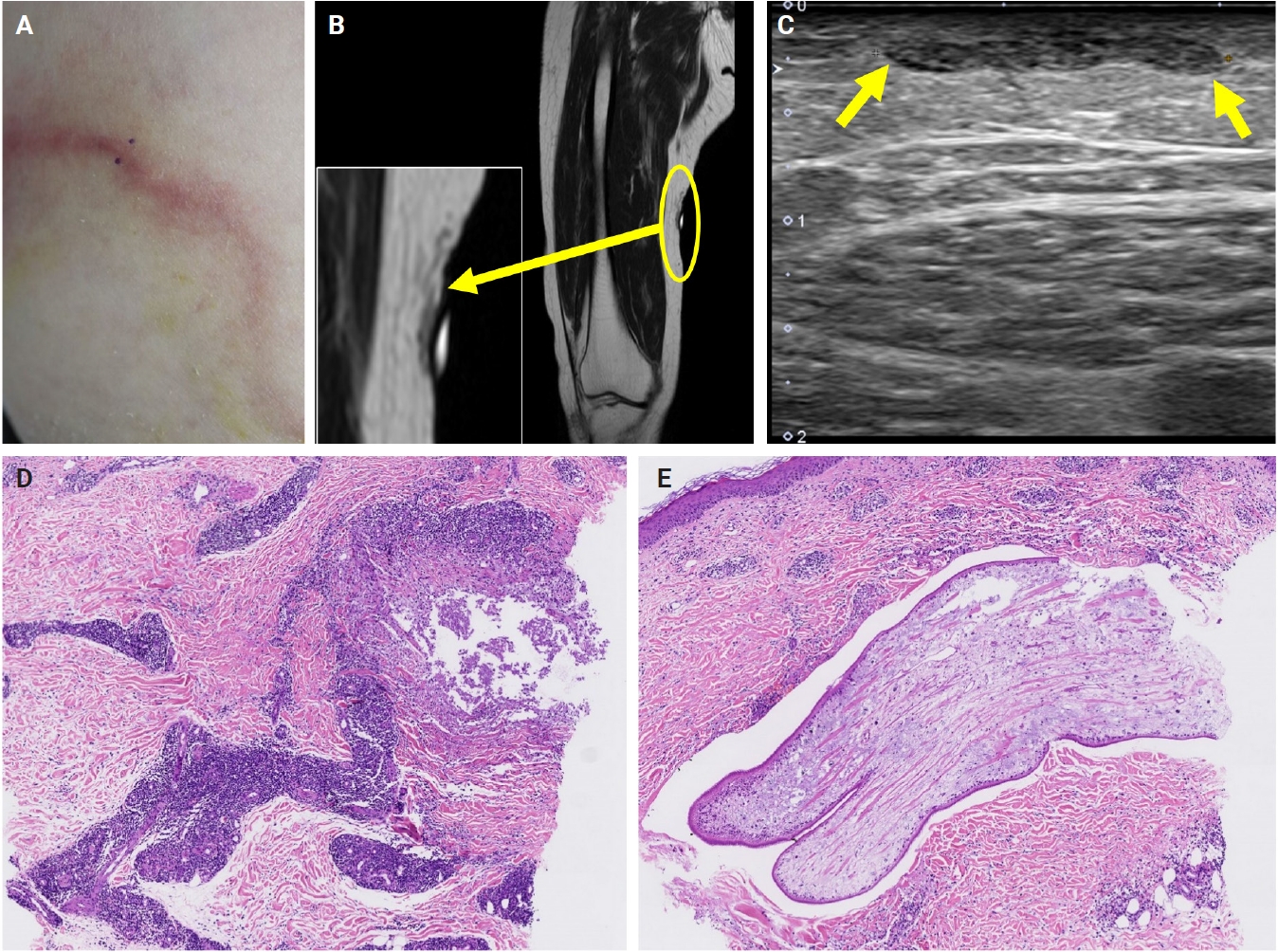

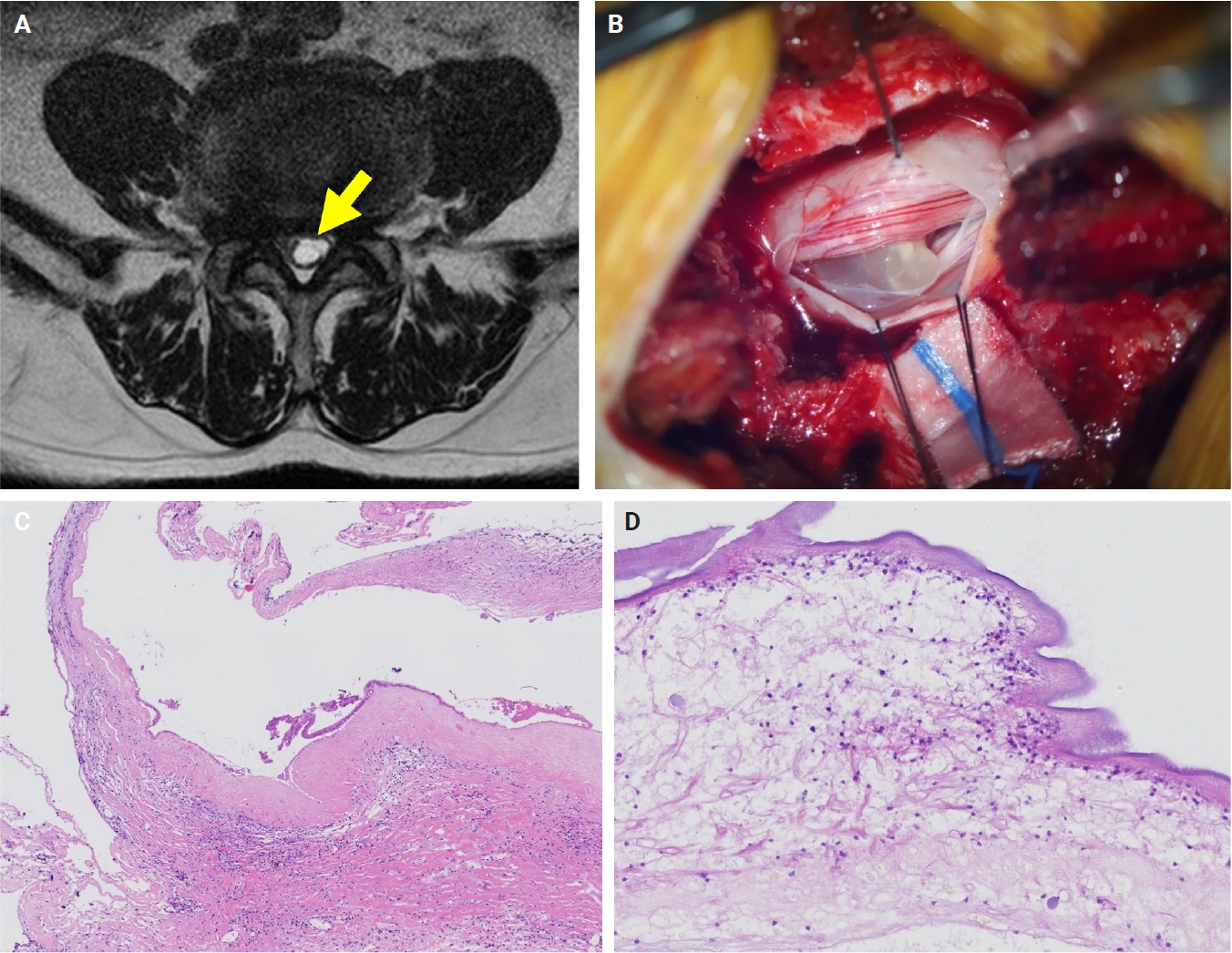

- The patients exhibited diverse clinical manifestations, often leading to diagnostic confusion. In cases 1 and 2, soft tissue masses yielded intact or live spargana during surgical excision (Figs. 1, 2). Case 1 involved a 64-year-old male with a crawling sensation in both legs and a history of consuming raw snake and frog meat. In case 2, a 58-year-old female had a long-standing thigh mass since childhood, with no known exposure history. Case 3 presented with multiple subcutaneous nodules mimicking benign cysts. Histologic examination revealed several larval structures embedded in the subcutaneous tissue, surrounded by eosinophilic and giant cell-rich inflammation (Fig. 3). Case 4 involved a neck mass initially suspected to be malignant lymphoma or metastatic carcinoma. Surgical excision revealed necrotic larval fragments with granulomatous inflammation (Fig. 4). Case 5 showed an erythematous, tender, S-shaped linear lesion on the thigh, clinically resembling phlebitis; histology demonstrated a necrotic worm in the dermis with microcalcifications and chronic inflammation (Fig. 5). In case 6, a spinal lesion caused neurologic symptoms and was radiologically interpreted as a nerve sheath tumor. Surgical resection revealed calcified parasite remnants within a yellowish translucent cystic mass (Fig. 6).

RESULTS

- Despite improvements in hygiene and public health, sporadic cases of sparganosis continue to occur. Pathologists should maintain a high index of suspicion for sparganosis in patients presenting with subcutaneous masses, even in the absence of a relevant exposure history. In our series, most patients were elderly women, and only two reported a history of consuming raw amphibians or reptiles; none had occupations associated with zoonotic exposure. These observations raise the possibility of an alternative, previously unrecognized route of infection, warranting further investigation. Potential routes could include consumption of undercooked fish or untreated drinking water and, although less probable, exposure to companion animals. While domestic dogs and cats are definitive hosts and do not typically transmit spargana to humans, prior studies from Iran, China, and Vietnam have reported Spirometra larvae in up to 40% of domestic animals [14-16]. Further population-based studies are needed to clarify the roles of sex, tissue characteristics, and environmental exposures in sparganosis epidemiology.

- Viable parasites were associated with symptoms such as a crawling sensation or localized warmth. Most diagnoses relied on remnants of the parasite, including calcareous corpuscles or tegumental fragments, rather than intact worms. When residing in human tissues, particularly confined subcutaneous spaces, spargana can cause necrotizing lesions of irregular shape, granulomas, and fibrosis due to tissue damage from parasite movement. Irregular or radiating borders of granulomatous inflammation and abundant eosinophilic infiltration are commonly observed in sparganosis and other forms of cutaneous larva migrans (CLM). However, sparganum larvae display highly characteristic features—including internal calcospherules and an undulating wavy tegument—which are absent in CLM.

- Spargana may survive for extended periods, especially in immune-privileged sites such as the brain and eyes [17-20], possibly due to reduced immune surveillance. Experimental studies have demonstrated similar patterns, including variable preservation of parasite structures, granuloma formation, and chronic inflammation [21]. These findings correlate with our human cases, particularly those in which parasites had degenerated significantly.

- In our series, serological testing was performed in a few patients. Interestingly, in one case of spinal cord sparganosis, sparganum-specific ELISA yielded a negative result, whereas the cysticercosis antibody level was slightly elevated. Despite this discrepancy, histopathological examination confirmed sparganosis. This case highlights the potential cross-reactivity of ELISA with cysticercosis and underscores the limited reliability of serological testing in isolation. Therefore, serological results should be interpreted with caution, particularly in endemic areas for both sparganosis and cysticercosis, and histopathology remains the gold standard for definitive diagnosis.

- Imaging findings vary by site and stage of infection. Early lesions or live worms may appear as mobile tubular structures, whereas older lesions often show nonspecific low-density areas, calcifications, fibrosis, or cystic changes. Such lesions may be misdiagnosed as complicated epidermal cysts, organized abscesses, or post-traumatic pseudocysts. In our series, one patient with a lateral neck mass (case 3) was initially suspected to have metastatic lymph node involvement. The most significant histopathologic diagnostic pitfall is likely confusion with a tuberculous lesion due to an acellular necrotic center surrounded by granulomatous reaction. Histopathological distinction between sparganosis and cysticercosis may also pose challenges, especially when specimens are old, fragmented, or degenerated. In such circumstances, the absence of a bladder wall and fibrillary stroma and the presence of longitudinal smooth muscle bundles and calcareous corpuscles are helpful features favoring sparganosis. Careful recognition of these features is essential to avoid misdiagnosis, particularly in small biopsy samples.

- Subcutaneous sparganosis should be distinguished from other conditions presenting with nodular lesions, including Kimura disease. Both entities may appear as slowly enlarging, painless subcutaneous nodules with marked tissue eosinophilia and reactive fibrosis. However, the absence of characteristic histopathologic features of Kimura disease—such as lymphoid follicular hyperplasia, eosinophilic microabscesses, and florid vascular proliferation—together with the presence of larval remnants embedded in granulomatous lesions, are key clues to sparganosis. Awareness of this differential diagnosis is essential for accurate evaluation of subcutaneous nodules in endemic areas.

- Although previous reports have consistently documented a male predominance in sparganosis, our series showed a striking predominance of female patients. This may reflect greater sensitivity in detecting lesions or a higher likelihood of seeking medical attention among women. Additionally, the relatively softer subcutaneous or soft tissue composition in females could provide a more favorable microenvironment for Spirometra larvae.

- Although sparganosis has become increasingly rare, it remains an important differential diagnosis for subcutaneous masses, particularly in endemic areas. Most cases are diagnosed histopathologically, often without prior clinical suspicion. Recognizing the characteristic histologic features—even in the absence of intact worms—is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate patient management.

DISCUSSION

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of BRMH (No.10-2025-41) and the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analyzed during the study are included in this published article.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: JEK. Data curation: JEK, JY, YAK, JHP, HEP, HBS. Investigation: JEK, JY. Project Administration: JEK, JY. Resources: JEK, JY, YAK, JHP, HEP. Writing—original draft preparation: JEK, JY. Writing—review & editing: all authors. Approval of the final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

J.H.P., a contributing editor of the Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding to declare.

| No. | Sex | Age (yr) | Nation | Location | Imaging | Recurrences | Sp-SSA | Hx | CC | Clinical diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 64 | Korean | Lower leg | US | Yes | Pos | Yes | Migrating mass | Infection |

| 2 | F | 58 | Korean | Lower leg | US | No | N/A | Yes | Fluctuant mass | Infection |

| 3 | F | 74 | Korean | Trunk | N/A | No | N/A | No | Mass with heating sense | Unknown |

| 4 | F | 53 | Chinese | Neck, SC | US, CT | No | Pos | No | Mass | M. lymphoma |

| 5 | F | 76 | Korean | Lower leg | US, MRI | No | Pos | No | Tender mass | Phlebitis |

| 6 | M | 79 | Korean | Spinal cord | MRI | No | Nega | No | Leg numbness | Neurogenic tumor |

| 7b | F | 46 | Korean | Breast | US, MMG | No | N/A | No | N/A | Fat necrosis |

| 8b | F | 69 | Korean | Breast | US, MMG | No | N/A | No | N/A | Infection |

| 9 | M | 52 | Korean | Trunk | US | No | N/A | No | N/A | Unknown |

| 10 | F | 57 | Korean | Lower leg | N/A | No | N/A | No | Palpable mass | Inflammatory nodule |

| 11 | F | 60 | Korean | Breast | US, MMG | No | N/A | No | Mass | Inflammatory nodule |

| 12 | F | 70 | Korean | Breast | US, MMG | No | N/A | No | Mass | Benign tumor |

| 13 | M | 62 | Korean | Pubic, SC | CT | No | N/A | No | Mass | Benign tumor |

| 14 | M | 73 | Korean | Lower leg | US, MRI | No | N/A | No | Mass | M. lymphoma |

| 15 | F | 83 | Korean | Lower leg | US | Yes | Pos | No | Multiple mass | Infection |

Nation, Nationality; Sp-SSA, sparganosis serum specific antibody; Hx, history of drinking unfiltered water or ingestion of raw frog/snakes; CC, chief complaint; US, ultrasonography; Pos, positive; N/A, not assessed; CT, computed tomography; M. lymphoma, malignant lymphoma; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; Neg, negative; MMG, mammography; SC, subcutis.

aSparganum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was negative but cysticercosis antibody was slightly elevated, while histopathology confirmed sparganosis;

bCases previously reported [10].

- 1. Liu Q, Li MW, Wang ZD, Zhao GH, Zhu XQ. Human sparganosis, a neglected food borne zoonosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2015; 15: 1226-35. ArticlePubMed

- 2. Kim JG, Ahn CS, Sohn WM, Nawa Y, Kong Y. Human sparganosis in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2018; 33: e273. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 3. Cho JH, Lee KB, Yong TS, et al. Subcutaneous and musculoskeletal sparganosis: imaging characteristics and pathologic correlation. Skeletal Radiol 2000; 29: 402-8. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 4. Kim HS, Cha ES, Kim HH, Yoo JY. Spectrum of sonographic findings in superficial breast masses. J Ultrasound Med 2005; 24: 663-80. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 5. Kim HY, Kang CH, Kim JH, Lee SH, Park SY, Cho SW. Intramuscular and subcutaneous sparganosis: sonographic findings. J Clin Ultrasound 2008; 36: 570-2. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Choi SJ, Park SH, Kim MJ, Jung M, Ko BH. Sparganosis of the breast and lower extremities: sonographic appearance. J Clin Ultrasound 2014; 42: 436-8. ArticlePubMed

- 7. Wiwanitkit V. A review of human sparganosis in Thailand. Int J Infect Dis 2005; 9: 312-6. ArticlePubMed

- 8. Koo M, Kim JH, Kim JS, Lee JE, Nam SJ, Yang JH. Cases and literature review of breast sparganosis. World J Surg 2011; 35: 573-9. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 9. Anantaphruti MT, Nawa Y, Vanvanitchai Y. Human sparganosis in Thailand: an overview. Acta Trop 2011; 118: 171-6. ArticlePubMed

- 10. Oh MY, Kim KE, Kim MJ, et al. Breast sparganosis presenting with a painless breast lump: report of two cases. Korean J Parasitol 2019; 57: 179-84. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Hwang M, Baek HJ, Lee SM. Apparent sparganosis presenting as a palpable neck mass: a case report and review of literature. Taehan Yongsang Uihakhoe Chi 2020; 81: 1210-5. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 12. Okino T, Yamasaki H, Yamamoto Y, et al. A case of human breast sparganosis diagnosed as spirometra type I by molecular analysis in Japan. Parasitol Int 2021; 84: 102383.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Liu W, Gong T, Chen S, et al. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and prevention of sparganosis in Asia. Animals (Basel) 2022; 12: 1578.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Hong Q, Feng J, Liu H, et al. Prevalence of Spirometra mansoni in dogs, cats, and frogs and its medical relevance in Guangzhou, China. Int J Infect Dis 2016; 53: 41-5. ArticlePubMed

- 15. Beiromvand M, Rafiei A, Razmjou E, Maraghi S. Multiple zoonotic helminth infections in domestic dogs in a rural area of Khuzestan Province in Iran. BMC Vet Res 2018; 14: 224.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 16. Nguyen YT, Nguyen LA, Van Dong H, Duong HD, Yoshida A. Molecular identification of sparganum of Spirometra mansoni isolated from the abdominal cavity of a domestic cat in Vietnam. J Vet Med Sci 2024; 86: 96-100. ArticlePubMed

- 17. Nobayashi M, Hirabayashi H, Sakaki T, et al. Surgical removal of a live worm by stereotactic targeting in cerebral sparganosis: case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2006; 46: 164-7. ArticlePubMed

- 18. Yang JW, Lee JH, Kang MS. A case of oular sparganosis in Korea. Korean J Ophthalmol 2007; 21: 48-50. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 19. Nkwerem S, Goto T, Ogiwara T, Yamamoto Y, Hongo K, Ohaegbulam S. Ultrasound-assisted neuronavigation-guided removal of a live worm in cerebral sparganosis. World Neurosurg 2017; 102: 696.Article

- 20. Hu J, Liao K, Feng X, et al. Surgical treatment of a patient with live intracranial sparganosis for 17 years. BMC Infect Dis 2022; 22: 353.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 21. Chang KH, Lee GJ, Han MH, et al. An experimental study on imaging diagnosis of cerebral sparganosis. J Korean Radiol Soc 1995; 33: 171-82. Article

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link-

Cite this Article

Cite this Article

- Cite this Article

-

- Close

- Download Citation

- Close

- Figure

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 6.

Graphical abstract

| No. | Sex | Age (yr) | Nation | Location | Imaging | Recurrences | Sp-SSA | Hx | CC | Clinical diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 64 | Korean | Lower leg | US | Yes | Pos | Yes | Migrating mass | Infection |

| 2 | F | 58 | Korean | Lower leg | US | No | N/A | Yes | Fluctuant mass | Infection |

| 3 | F | 74 | Korean | Trunk | N/A | No | N/A | No | Mass with heating sense | Unknown |

| 4 | F | 53 | Chinese | Neck, SC | US, CT | No | Pos | No | Mass | M. lymphoma |

| 5 | F | 76 | Korean | Lower leg | US, MRI | No | Pos | No | Tender mass | Phlebitis |

| 6 | M | 79 | Korean | Spinal cord | MRI | No | Neg |

No | Leg numbness | Neurogenic tumor |

| 7 |

F | 46 | Korean | Breast | US, MMG | No | N/A | No | N/A | Fat necrosis |

| 8 |

F | 69 | Korean | Breast | US, MMG | No | N/A | No | N/A | Infection |

| 9 | M | 52 | Korean | Trunk | US | No | N/A | No | N/A | Unknown |

| 10 | F | 57 | Korean | Lower leg | N/A | No | N/A | No | Palpable mass | Inflammatory nodule |

| 11 | F | 60 | Korean | Breast | US, MMG | No | N/A | No | Mass | Inflammatory nodule |

| 12 | F | 70 | Korean | Breast | US, MMG | No | N/A | No | Mass | Benign tumor |

| 13 | M | 62 | Korean | Pubic, SC | CT | No | N/A | No | Mass | Benign tumor |

| 14 | M | 73 | Korean | Lower leg | US, MRI | No | N/A | No | Mass | M. lymphoma |

| 15 | F | 83 | Korean | Lower leg | US | Yes | Pos | No | Multiple mass | Infection |

Nation, Nationality; Sp-SSA, sparganosis serum specific antibody; Hx, history of drinking unfiltered water or ingestion of raw frog/snakes; CC, chief complaint; US, ultrasonography; Pos, positive; N/A, not assessed; CT, computed tomography; M. lymphoma, malignant lymphoma; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; Neg, negative; MMG, mammography; SC, subcutis. Sparganum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was negative but cysticercosis antibody was slightly elevated, while histopathology confirmed sparganosis; Cases previously reported [

E-submission

E-submission